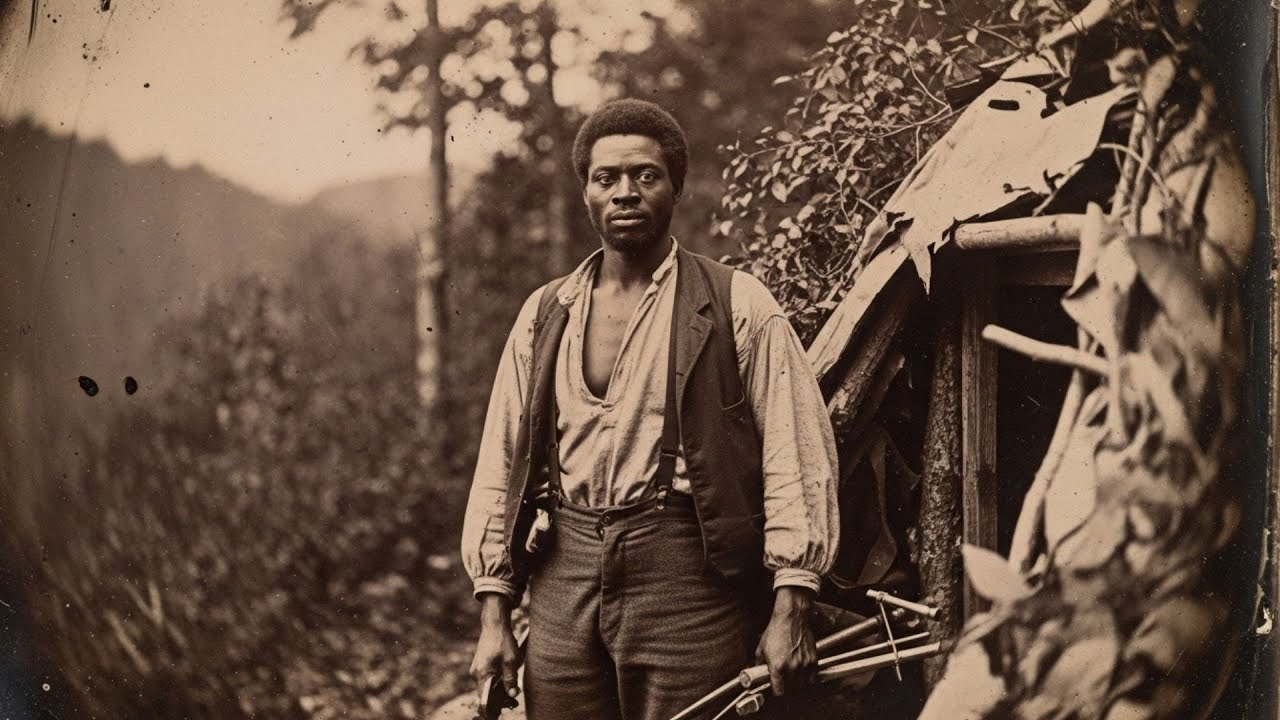

(1851) The Mountain Man Slave Who Built a ‘Simple Trap’ That Caught Every Master Hunting Him | HO

Welcome to one of the most unsettling chapters in Appalachian history — a story whispered across generations, written not in ink but in absence. Before you read further, imagine standing in the shadowed hollows of McDowell County, West Virginia, where the forest still feels alive, where every creak and whisper of wind seems to remember.

The year was 1851, when the first disappearances began. Wealthy landowners who ventured too far into the dense Appalachian wilderness simply never returned. At first, their vanishings were attributed to the hazards of the terrain — sinkholes, bears, flash floods, the countless ways the mountains swallowed men whole. But by winter, a pattern emerged too deliberate to ignore, and it all pointed back to one man: Elijah Brown, a fugitive slave whose brilliance turned the wilderness into a fortress, and the pursuit of him into a nightmare.

The Master’s Obsession

Thomas Hail, a tobacco baron from the valley, was the first to vanish. His plantation records — uncovered in 1962 — show that in July 1851, he reported the escape of one “Elijah,” a man of unusual mechanical skill. Hail’s wife, Sarah, kept a journal. In one entry she wrote:

“Thomas speaks of nothing else. There is something in his eyes when he speaks of Elijah that frightens me more than the thought of a runaway in our hills.”

Elijah wasn’t an ordinary field hand. He had been trained as a carpenter and engineer, designing irrigation systems that transformed Hail’s estate into one of the most productive in the county. His mind was precise — too precise, perhaps, for a man the law considered property.

When he fled, Hail took it personally. He formed his own search party, insisting he knew “how Elijah thinks.” On August 3rd, 1851, he and five men rode into the mountains. They never came back.

Weeks later, a search party found their abandoned camp, supplies still laid out, and strange markings on trees nearby — lines, pulleys, and counterweights made of rawhide and wood. Nothing else. Not even bones.

Sarah wrote that she dreamt of her husband’s voice “calling from inside the mountain, as though the earth had swallowed him whole, yet kept him living within its belly.”

The Man Who Made the Mountains Think

Before his escape, Elijah Brown had spent years building machines for his master — irrigation levers, drainage pulleys, even restraining devices used on other slaves. He learned not just how to construct mechanisms, but how they could shape behavior.

And somewhere deep in the mountains, Elijah began to build again.

A year after Hail vanished, a trapper named Josiah Miller reported stumbling upon “a system of ropes and pulleys strung between trees with such cunning design I mistook it for witchcraft.”

By 1852, plantation owners were no longer speaking of a runaway — they were speaking of an adversary. One letter written by Frederick Wilson to his cousin in Richmond confessed:

“We no longer hunt a man but contend with a mind that uses the forest as both snare and sanctuary. Our men vanish without trace. Their dogs return trembling.”

The Bounty Hunter Who Never Returned

In the fall of 1852, a notorious slave catcher from North Carolina, Ezekiel Monroe, arrived in McDowell County. He boasted of never failing to capture his quarry.

On October 12th, he set out with six men and dogs. Ten days later, silence. Two weeks later, still no word. Locals who followed their trail said the woods “went dead” — no birds, no wind, no sound but the crunch of their own boots.

By winter, Monroe and his team were officially declared missing. Not a body was ever found. It was the last recorded attempt to capture Elijah Brown.

After that, the land itself gained a new reputation. Entire valleys became unmapped territory, marked on local charts only as “unsuitable for settlement.”

A Discovery Buried in 1967

More than a century later, during preparations for a proposed highway, state archaeologists uncovered something remarkable in a remote hollow near the Virginia border.

Dr. Margaret Donovan, who led the 1967 dig, described a hidden living complex carved directly into the mountainside — “part shelter, part laboratory.” The site was rigged with counterweights, alarm systems, and concealed pits. Some were designed not to kill, but to contain.

She wrote in her private notes, later suppressed by state officials:

“The engineering skill evident here far exceeds what one would expect from a man with no formal training. The interconnected traps form a network — a mechanical nervous system — that could respond to human presence.”

Among the relics found were fragments of a journal written on bark and leather. One passage read:

“The mountain itself can be made to serve as both fortress and weapon. Each man who comes seeking me now serves as both experiment and refinement. Each failure improves my design.”

Another note, found in a small bound book nearby, detailed “studies of human behavior under isolation.” It recorded how long captives remained calm before panic set in, how sound, darkness, and circular paths could collapse reason.

Elijah, it seemed, had turned the methods of captivity into his own science of liberation.

The Man Who Taught the Mountain to Learn

Evidence suggests Elijah lived in those mountains for at least two decades, perfecting his mechanisms. Reports from 1855 onward describe “wooden machinery that groaned after rain,” paths that looped endlessly, and eerie silences that sent hunters fleeing in panic.

A single survivor from Monroe’s party was found delirious months later. His final words, recorded by a local doctor:

“He built something up there that’s more than traps. He built a place where the hunter becomes the hunted.”

By 1860, the disappearances stopped — not because Elijah was captured, but because no one dared go back.

The Archaeologist’s Warning

Dr. Donovan’s full report was sealed after her death in 1983. But in a letter to a colleague she wrote:

“What we uncovered was not a hideout. It was a system of control — an early, terrifying prototype of psychological warfare. The mechanisms weren’t meant to harm. They were meant to teach. And I believe their creator succeeded.”

Her findings hinted that the system may have remained partially functional for decades. Some traps appeared to have been maintained into the early 1900s — perhaps by others who stumbled upon Elijah’s designs and kept them alive, knowingly or not.

The Mountain That Remembered

Folklore filled the gaps history refused to answer. In the early 1900s, Appalachian families told stories of a “mountain man” who punished greed and cruelty by making trespassers vanish. Children were warned not to hunt “what isn’t theirs to hunt.”

By the 1930s, locals spoke of hearing “wooden gears turning under the earth” after heavy rains. In the 1950s, hikers reported meeting an elderly Black man deep in the forest who seemed to know their names, warning them which paths to avoid before disappearing into the mist.

The descriptions — a man with finely crafted tools, eyes both kind and watchful — matched accounts recorded as far back as the 1870s. Whether it was Elijah himself or a figure born from his legend, no one could say.

The Map That Shouldn’t Exist

In 1969, a descendant of the Hail family uncovered a sealed envelope among inherited papers. Inside was a crude map drawn on animal hide, marked with strange symbols resembling mechanical diagrams. Along the margin, in faded ink:

“Not all who wander these paths are truly lost. Some are exactly where they have chosen to be.”

Handwriting analysis showed it didn’t match Thomas Hail — nor anyone else in his family. The map was turned over to state officials. It promptly disappeared from the archives during a relocation in 1972.

Echoes of the Design

Even today, certain valleys in McDowell County remain curiously untouched by development. Attempts to build logging roads have failed due to “equipment malfunctions” and “surveying discrepancies.” Locals talk about a feeling — a sense of being watched — when they wander too far from the main trails.

A 2001 archaeological survey using ground-penetrating radar detected what appeared to be underground tunnels arranged in deliberate geometric patterns. When excavation began, only natural rock formations were found — yet several team members insisted the formations seemed “sculpted by intention.”

The lead archaeologist later admitted privately:

“It was as if the mountain decided what we were allowed to see.”

Legacy of the Hunter Turned Hunted

To historians, Elijah Brown is a ghost in the records — an escaped slave with no death certificate, no grave, and a genius that shouldn’t have been possible for a man denied education. Yet his existence is undeniable, written into the landscape itself.

To psychologists, his story represents the earliest known case of environmental manipulation as a form of resistance — transforming the landscape into an invisible rebellion.

And to the people of McDowell County, he remains both protector and curse. They say he taught the mountains to remember cruelty, to turn injustice back upon its pursuers.

In 1868, years after her husband’s disappearance, Sarah Hail wrote one last diary entry:

“I dreamed of Thomas again. He sat in a small wooden room, surrounded by devices of strange design. He looked at me and said, ‘I understand now what he wanted me to understand — what it means to belong to another’s design.’”

Perhaps that’s the truest legacy of Elijah Brown — not vengeance, but transformation. The mountains themselves became his testament: silent, watchful, and unwilling to let the world forget that once, a man who was supposed to be broken built a trap so perfect that no master ever escaped it.

News

A Stepdaughter Infected Her Stepmother With HIV After A Secret Affair, Leading To Murder | HO

A Stepdaughter Infected Her Stepmother With HIV After A Secret Affair, Leading To Murder | HO On a gray Seattle…

Chicago: Wife Found Out Husband’s Sister Was Actually His Trans Lover – It Led To M*rder | HO

Chicago: Wife Found Out Husband’s Sister Was Actually His Trans Lover – It Led To M*rder | HO On the…

Bride 𝐃𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐦 During Honeymoon, Year Later He Was Standing At Her Door .. | HO!!!!

Bride 𝐃𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐦 During Honeymoon, Year Later He Was Standing At Her Door ..| HO!!!! On a quiet weekday morning,…

The Chilling History of the Appalachian Bride — Too Macabre to Be Forgotten | HO!!!!

The Chilling History of the Appalachian Bride — Too Macabre to Be Forgotten | HO!!!! PART 1 — A Wedding…

Vanished In The Ozarks, Returned 7 Years Later, But Parents Didn’t Believe It Was Him | HO!!!!

Vanished In The Ozarks, Returned 7 Years Later, But Parents Didn’t Believe It Was Him | HO!!!! PART 1 —…

The Bricklayer of Florida — The Slave Who 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐝 11 Overseers Without Leaving a Single Clue | HO!!!!

The Bricklayer of Florida — The Slave Who 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐝 11 Overseers Without Leaving a Single Clue | HO!!!! TRUE CRIME…

End of content

No more pages to load