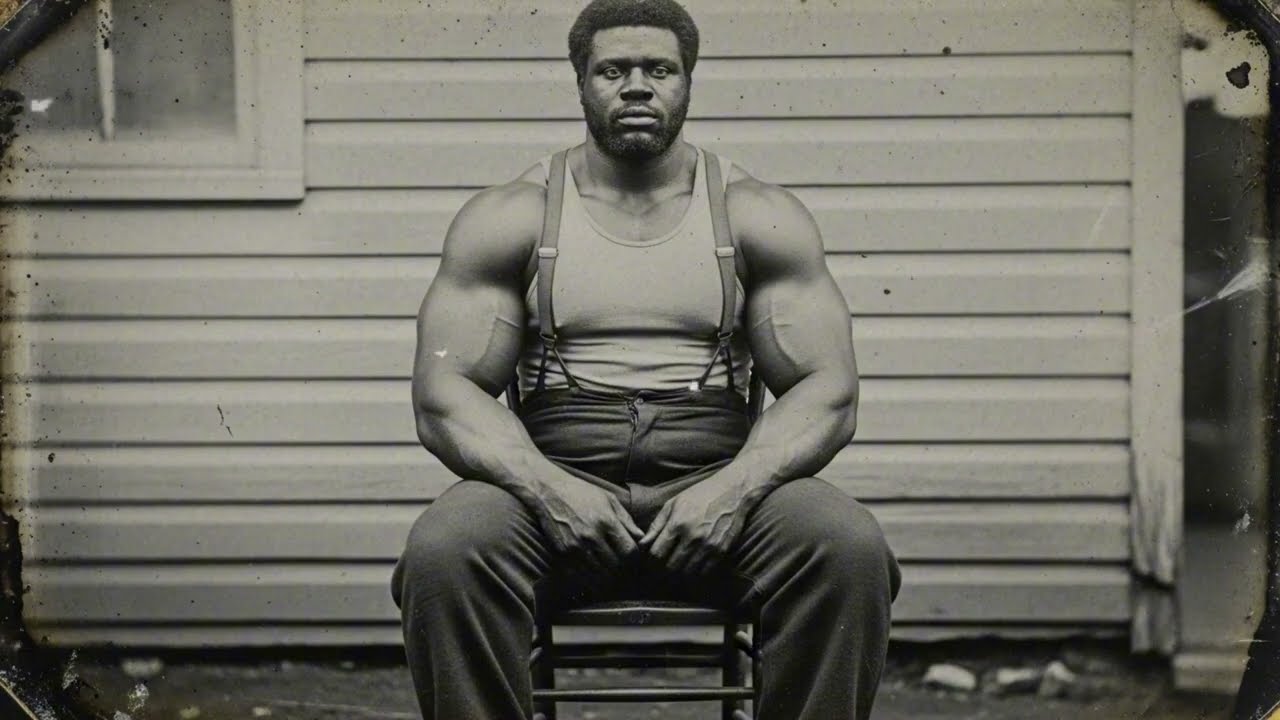

(1856, Jacob Terrell) The Black Man So Strong That 12 Overseers Could Not Restrain Him | HO

In the brittle, humidity-warped plantation records of northeastern Alabama, there is an entry so extraordinary that historians still struggle to categorize it. Dated March 1856, the report describes an incident at Harrington Plantation, where twelve armed, trained, legally empowered white overseers failed to restrain a single enslaved man.

The men were not inexperienced. They were not drunk. They were not unprepared. They had the advantage of weapons, numbers, and authority.

And yet they failed.

What they witnessed that morning would leave deep psychological scars:

Three overseers resigned within days

One permanently disfigured

Two refused for the rest of their lives to discuss the event

The plantation owner, Colonel Marcus Harrington, ordered every document sealed. Families were paid for silence. No one spoke publicly. No newspaper covered it.

And yet the story survived.

Not because the colonel preserved it — but because the enslaved people did.

What happened that morning was not supernatural.

It was not myth.

It was not an exaggeration born from trauma.

It was something far more dangerous.

It was proof that even the most brutal system of American slavery depended on the one thing enslavers could never fully control: a person’s decision to comply.

To understand how one man broke the logic of an entire plantation, we must understand him — the man who walked off the Harrington estate and vanished into history.

This is the story of Jacob Terrell, and the case that terrified every slaveholding region of the South.

I. Harrington Plantation: A Fortress Built on Cotton and Control

In 1856, Harrington Plantation stood as one of the most profitable operations in Madison County. Spread across 3,000 acres of Alabama bottomland, carved by the Talapoosa River, it was an empire of cotton and coercion.

The estate supported:

240 enslaved laborers

17 white overseers

1,500 bales of cotton annually

A meticulously organized infrastructure of fields, mills, gins, cabins, and punishment sites.

The mansion itself was a 16-room Greek Revival monument to the colonel’s power — but the true engine of Harrington Plantation lay not in its architecture, but in its mathematical cruelty.

Colonel Marcus Harrington kept detailed ledgers on every human being he owned:

daily output

hours worked

punishments delivered

injuries sustained

deaths recorded

He viewed himself not as a tyrant, but as a master strategist. He prided himself on precision. On order. On efficiency.

Which is why the arrival of Jacob Terrell in the autumn of 1852 seemed like a perfect acquisition.

II. The Man Who Was Not Supposed to Resist

Purchased in Richmond at the staggering price of $2,000 — triple the prevailing rate — Jacob caught the colonel’s eye immediately.

His physical description remains preserved in archives:

Age: about 28

Height: 6’7’’

Weight: approximately 260 pounds

Build: “remarkable constitution,” dense, ironworker muscle

History: born and raised on an iron plantation

Temperament: quiet, compliant, no history of rebellion

Unlike most enslaved field laborers, Jacob came from industrial work — furnaces, forges, timber operations. He was strong in a different way. Not wiry endurance, but compact, pressure-forged power.

He rarely spoke. Worked efficiently. Never challenged authority.

For nearly four years, Jacob behaved exactly as a high-value laborer was expected to. Overseers described him as:

“Reliable”

“Mechanical”

“Predictable”

But in the winter of 1855, something shifted.

A letter reached him.

A letter he was never supposed to see — or survive.

III. The Letter That Broke Something Inside Him

Enslaved people were forbidden from receiving correspondence, yet somehow, a single piece of paper found its way to Harrington Plantation. Witnesses later recalled a haunting moment behind the cookhouse.

Jacob stood motionless, staring at the letter.

His hands shook.

His face looked hollow.

As if a man had suddenly realized he was already dead.

No one knew the contents at the time.

Not the overseers.

Not the colonel.

Not even the enslaved people who watched Jacob’s soul collapse in silence.

Later, the truth would emerge.

But by then, the chain reaction had already begun.

Overseers noticed small changes:

Jacob asked about property boundaries

about river depths

about distances to neighboring counties

about escape routes

He wasn’t planning rebellion.

He wasn’t planning violence.

He was planning an ending.

Old Samuel described Jacob’s presence as:

“The stillness before a sky turns green and a tornado touches down.”

What none of them understood, not yet, was that Jacob wasn’t becoming dangerous.

He was abandoning fear.

And once a man no longer fears consequences, he becomes impossible to control.

IV. March 14, 1856: The Morning Fog

The morning began uneventfully. Fog wrapped the plantation in a muffled gray silence, the kind that made distance deceptive and shadows strange.

Work began at dawn.

At 7:15 a.m., three overseers confronted Jacob at the cotton press.

A dispute.

A refusal.

A mention of the intercepted letter.

Witnesses disagree on the exact trigger, but all accounts align on what followed.

Overseer Thomas Gibbard raised his leather strap.

He struck Jacob.

Jacob did not flinch.

Eli Strauss grabbed Jacob’s arm.

It felt, he later testified,

“like gripping an oak beam.”

Jacob didn’t pull away.

Didn’t swing.

Didn’t resist in any violent way.

He simply refused to move.

What happened next would terrify everyone present.

V. Twelve Armed Men Against One Man Who Chose Not to Bend

Gibbard, humiliated, fired his pistol into the air, summoning reinforcements.

Four more overseers arrived.

Then five.

Then twelve — the maximum number on the property.

Twelve armed white men, trained in restraint and punishment, positioned themselves around one unarmed man.

They moved in simultaneously.

What followed appeared in every testimony:

Bodies hitting the ground.

Bones cracking.

Overseers colliding with each other.

Men thrown off balance by their own momentum.

A circle of white men falling, one after another — without Jacob landing a single blow.

It wasn’t a fight.

It was a demonstration of immovability.

Not superhuman strength.

Not mystical force.

But absolute psychological conviction.

A wall that had decided not to fall.

When the colonel arrived minutes later, he found:

four overseers injured

one unconscious

another with broken ribs

a seventh with a dislocated shoulder

the remaining men shaken and silent

Jacob stood in the center of the clearing, breathing heavily but untouched.

The colonel drew his pistol.

The world froze.

Witnesses described a silence so absolute it felt alive.

And then Jacob spoke.

VI. “I Ain’t Here No More.”

His voice was calm.

Clear.

Final.

“I ain’t here no more.

You might be looking at me, but I ain’t here.

I been gone since that letter came.”

He turned and walked toward the woods.

No running.

No fear.

No hesitation.

The colonel ordered the overseers to stop him.

No one moved.

Jacob disappeared into the treeline and into legend.

VII. The Search That Found Nothing

The colonel launched an eleven-day manhunt involving:

23 armed riders

bloodhounds

neighboring plantations

river patrols

boundary checkpoints

Jacob’s trail lasted half a mile.

Then vanished at a creek.

The dogs lost the scent.

Not upstream.

Not downstream.

Nowhere.

It was as if Jacob stepped into the water… and ceased to exist.

No tracks.

No clothes.

No body.

No sign of struggle.

He was simply gone.

And Harrington Plantation began to crumble.

VIII. Overseers Break — The System Cracks

Three overseers resigned within days.

Gibbard, once the most feared man on the estate, wrote:

“I can no longer maintain discipline.

The system contains flaws I had not previously recognized.”

Strauss left next.

Pritchard drank himself into eventual dismissal.

The colonel, obsessed, launched his own investigation — leading him to the truth of the letter that had destroyed Jacob’s willingness to submit.

A letter from Jacob’s wife, sold to Georgia:

she was pregnant

she begged him not to attempt rescue

she knew they would never see each other again

she asked him to “stay whole inside”

The letter had been shown to him by an overseer.

A cruelty meant to break him.

It succeeded — just not in the way they expected.

IX. The Bundle in the Hollow Tree

Nearly a month after the escape, a cloth bundle was discovered wedged into a hollow oak near the woods.

Inside were:

a wooden carving of two figures holding hands

a torn paper with a Georgia address

an iron foundry tag

and a note

The note revealed everything:

“I ain’t running.

I’m walking slow.

Going to Georgia.

Might take four months if I move careful.

If I make it, you won’t hear of me again.

If I don’t, at least I died trying to get back to what matters.”

And then, the line that terrified the colonel most:

“I wasn’t fighting that morning.

I was showing you I ain’t a thing you can move no more.

You can kill a man like that.

But you can’t work him.”

The colonel burned the note.

But the story spread anyway.

X. A Plantation Begins to Collapse

After the incident:

escapes increased

resistance became organized

people began standing together

punishment stopped working

Fifty enslaved people once stood silently between an overseer and a man about to be whipped — humming until the colonel backed down.

It was passive resistance.

Nonviolent.

But devastatingly effective.

The colonel tried:

more overseers

more patrols

informants

restricting gatherings

None of it worked.

Because the danger wasn’t Jacob.

It was the idea Jacob planted.

XI. The Letters From Georgia

In January 1857, nearly a year after the escape, the colonel received a letter in Jacob’s handwriting.

It said only three things:

“I made it.

I am with my wife and son.

And you don’t own nobody, Colonel.

You just got a system that makes it hard for people to choose different.

I proved it ain’t impossible.”

Another letter came months later.

Even more dangerous.

Jacob wrote:

“What happened after I left — that wasn’t me.

That was them deciding for themselves.

You can’t stop that.

Not with punishment.

Not with fear.

Not with guns.”

The colonel broke.

XII. Harrington Plantation Falls Apart — And the South Begins to Tremble

By 1858:

overseers quit in waves

escapes spread to other plantations

resistance movements mirrored Jacob’s example

rumors spread across Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia

Jacob had become a symbol, whispered from cabin to cabin:

“The man twelve couldn’t move.”

The colonel sold the plantation.

The new owner failed too.

Nothing could restore order.

Because Jacob had exposed a truth slaveholders never wanted spoken:

Slavery was not enforced by chains or guns.

It was enforced by belief.

And belief could be broken.

XIII. The Final Mystery: What Became of Jacob?

Official records fall silent after 1860.

But a Philadelphia abolitionist newspaper published an anonymous account by a formerly enslaved man matching Jacob’s details. It contained one unforgettable line:

“I didn’t fight those men. I just decided they couldn’t decide for me anymore.”

Some believe Jacob lived quietly in the North.

Some believe he died on the journey.

Some believe he reached freedom, raised his family, and told no one who he once was.

But his legacy is undeniable.

Because on that fog-covered morning in 1856, on a plantation built on domination, one man made a decision:

He refused to be movable.

And twelve armed men discovered what it meant when a human being decided he would no longer participate in his own oppression.

Conclusion: The Strength That Terrified a System

Jacob Terrell did not topple slavery.

But he cracked something inside it.

He revealed a terrifying truth slaveholders never wanted to confront:

Their power depended entirely on other people believing they had none.

And once a single person stopped believing —

once one man stood immovable against twelve —

the entire logic of the system trembled.

That was Jacob’s true strength.

Not muscle.

Not violence.

Not supernatural force.

But the unbreakable conviction that he was a man.

And no one — not even twelve overseers with whips, guns, and the law behind them — could make him forget it.

News

In Chicago Secret 𝐆𝐚𝐲 Affair Exposed At Funeral, Widow Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 With A Note in Her 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 | HO!!

In Chicago Secret 𝐆𝐚𝐲 Affair Exposed At Funeral, Widow Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 With A Note in Her 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 | HO!! Chicago…

The UNTOLD Truth Of Tracey Chapman’s Rise & Dramatic Fall… | HO!!

The UNTOLD Truth Of Tracey Chapman’s Rise & Dramatic Fall… | HO!! “Tracy Chapman” eventually went six-times platinum in the…

53YO Woman Tracks 25YO Lover to Texas—He Scammed Her for $100K, Then Married a Man. She brutally…. | HO!!

53YO Woman Tracks 25YO Lover to Texas—He Scammed Her for $100K, Then Married a Man. She brutally…. | HO!! It’s…

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent”

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent” By morning, the message…

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent”

Six Months After My Wife Gave Birth, My Friend Said, ”We Need To Talk. It’s Urgent” By morning, the message…

King Tut’s Mask Was Scanned Using Quantum Imaging — The Results Shocked Egyptology | HO”

King Tut’s Mask Was Scanned Using Quantum Imaging — The Results Shocked Egyptology | HO” For more than a century,…

End of content

No more pages to load