(1865, Sarah Brown) The Black girl with a photographic memory — she had a difficult life | HO

Prologue: A Gift Too Powerful for the World She Inherited

History has a way of forgetting the people it fears most.

In the turbulent spring of 1865, as the last gunshots of the Civil War echoed across a fractured nation and the 13th Amendment began to dissolve the legal framework of slavery, a seven-year-old Black girl in rural Georgia quietly began demonstrating abilities that defied everything white society believed about Black intelligence.

Her name was Sarah Brown.

She was born into bondage with a mind that worked like no other. What modern psychology would later call eidetic—photographic—memory, Sarah possessed naturally. She could recall pages, images, speeches, maps, entire conversations after a single glance or a single hearing. Perfectly. Without effort. As if her brain were a camera and the world was constantly imprinting itself upon her.

But in Reconstruction-era Georgia, a Black girl with genius wasn’t seen as a gift from God.

She was seen as a threat.

A threat to white supremacy.

A threat to historical lies.

A threat to the men who needed the past buried so they could rebuild their power unchallenged.

And because she could remember everything, she would spend her life punished for remembering—and eventually erased so thoroughly that only fragments of her existence survive.

This is her story.

Chapter I: Born Into Bondage, Raised in a World Fighting to Forget

Sarah Brown was born in 1858 on a small plantation in Wilkes County, Georgia. Not a grand cotton empire, but a subsistence farm that fed the Confederate army. The work was brutal. The overseers harsher. And the children raised beneath that system learned early that white men carried the right to your life in their pockets.

Her mother, Harriet, was a house servant—supposedly a “privileged” position, though in truth it simply meant greater vulnerability to the white men who prowled the halls of the main house. Her father’s identity was never written down, but the whispered rumors said enough.

From infancy, Sarah saw things she should never have seen. And by the time she was old enough to form memories, those memories clung to her with perfect clarity.

The violent last years of slavery imprinted themselves on her mind like ink on parchment.

When Union troops approached Georgia under Sherman, the plantation’s white family fled, leaving the enslaved population to a strange limbo: no longer enslaved in practice, but not yet secure in freedom. Men disappeared to join Union lines. Women hid in the woods, fearing retaliation. Everything was uncertain.

But Sarah saw it all.

And she never forgot a single detail.

When emancipation became law in 1865, Harriet took Sarah to Washington, Georgia—a small, rough settlement where freed Black families built makeshift communities out of nothing. The Freedmen’s Bureau barely reached the town, and white hostility burned hotter than the summer sun.

Harriet washed clothes until her hands bled, all to keep her daughter alive.

And yet, in this precarious new freedom, one possibility emerged that had been violently denied to generations of enslaved people:

school.

Chapter II: The Classroom Where a Prodigy Emerged

In late 1865, a one-room Black church doubled as a school. Its teacher was Martha Williams, a young freeborn Black woman from the North, educated by Quakers and deeply committed to Black literacy.

Classes were held after sunset by candlelight. Students ranged from 6 to 60, many exhausted from a full day’s labor. Most were learning the alphabet for the first time.

And then there was Sarah.

Martha noticed it on the first night: the girl learned the alphabet after a single lesson. By the second night, she could recite it backward. She copied letters perfectly, spacing and shaping them exactly as Martha wrote them.

Martha tested her with Bible verses. Sarah repeated them flawlessly after one reading—down to the punctuation marks.

She memorized entire pages.

Maps.

Diagrams.

Dates.

Every detail, no matter how small.

She remembered the location of words on the slate after the slate had been wiped clean.

It was beyond unusual. It was unprecedented.

Harriet confirmed what Martha feared:

No one had ever taught Sarah anything.

This was pure, natural genius.

And in Reconstruction Georgia, genius could be fatal.

The Black community agreed:

Keep Sarah’s abilities secret.

Protect her.

Hide her brilliance from white eyes.

But secrets rarely survive in a world committed to exposing and exploiting Black vulnerability.

Chapter III: The White Doctor Who Saw Opportunity

In spring 1866, Dr. Charles Morrison, a Freedmen’s Bureau physician from Pennsylvania, visited Washington to assess local conditions. He saw Martha’s school—and saw Sarah demonstrate her memory.

His scientific curiosity turned instantly into ambition.

He approached Harriet, insisting that Sarah undergo “medical examination.” Harriet resisted, but Dr. Morrison held federal authority. Refusal was dangerous.

Eventually, she felt she had no choice.

Dr. Morrison began testing Sarah obsessively:

—pages of medical texts

—anatomical diagrams

—random number strings

—photographs

—nonsense syllables

—maps

Sarah recalled everything with flawless accuracy.

Hours later.

Days later.

Her mind was a perfect recorder.

Morrison documented everything, writing reports that—if published—would have shattered every racist assumption about Black intellectual inferiority.

But he didn’t publish them.

Instead, he saw money.

By summer 1866, he began advertising exhibitions:

“THE REMARKABLE NEGRO GIRL WHO NEVER FORGETS.”

He rented halls. Sold tickets.

Used Sarah as entertainment.

Harriet tried to resist. Morrison threatened her. Told her she had no rights. That refusing him would cost her daughter far more.

So Sarah performed—night after night—before white crowds hungry for spectacle.

Some marveled.

Some sneered.

Some called her a fraud.

Some called her unnatural.

Ministers argued:

—Some claimed she was proof of Black humanity and divine intelligence.

—Others claimed she was demon-possessed.

But then came the moment that changed everything.

Chapter IV: The Girl Who Remembered Crimes White Men Needed Forgotten

In October 1866, during a public exhibition, an audience member handed Sarah a newspaper page from 1863—a Confederate-era report of a lynching in Wilkes County.

Sarah read the page for five seconds.

Then she recited the article word-for-word.

Then she described the accompanying illustration—a woodcut of the lynching scene.

Then, horrifying the room, she began naming the white men pictured.

“That’s Mr. Patterson.”

“That’s Mr. Willis.”

“That’s Sheriff Carver.”

The hall erupted.

Men jumped to their feet, shouting accusations. Calling Sarah a liar. Threatening violence. Demanding to know how a Black child could possibly recognize those men.

But she wasn’t guessing.

She remembered them—because she had seen them on the streets of Washington during her childhood.

She remembered everyone.

She remembered everything.

In one moment, Sarah’s ability crossed a line.

She had exposed the past—violence white society needed erased.

And once white men realized she could recall crimes they had committed, witnessed, or covered up, her existence became intolerable.

The next day, newspapers stopped writing about her entirely.

Dr. Morrison’s exhibitions were shut down by local threat.

White authorities warned him:

“Silence her.

Or we will.”

By early 1867, Morrison fled Georgia—taking all his scientific reports with him, never publishing a word.

Sarah was left behind.

Unprotected.

Exposed.

Marked as dangerous.

Chapter V: A Living Archive for a People Whose Stories Were Being Erased

White society feared Sarah.

Black society embraced her.

In mid-1867, Harriet moved them to Augusta, hoping a larger Black community and AME church networks would offer safety. There, Sarah came under the protection of Reverend Thomas Wilson, an AME minister with deep connections to northern abolitionists.

Under his guidance, Sarah’s abilities were used for a far more powerful purpose:

preserving Black memory.

Families who had been torn apart by slavery brought Sarah:

—photographs

—names

—stories

—rumors of where loved ones had been sold

—fragmentary histories of their lineage

Sarah remembered all of it.

Every detail.

She became a living genealogical archive for people whose pasts had been systematically destroyed. She memorized:

—enslaved marriages never recorded

—children sold to other states

—plantations where relatives had worked

—stories passed down orally

—birthplaces, burial sites, last known locations

Old men and women sought her out to tell their stories—stories no white historian would ever record.

She remembered every word.

Reverend Wilson wrote in his 1869 journal:

“She has become our living archive, preserving the memories of our people that no written record captures.

But she carries a terrible burden. She cannot forget the horrors she has witnessed.

I pray her suffering might serve a larger purpose.”

But danger was never far.

Chapter VI: The Attempt to Seize Her

By 1870, white authorities in Augusta launched an effort to have Sarah forcibly removed for “scientific study.” White doctors wanted to:

—measure her skull

—test her neurologically

—and, chillingly, they spoke openly about wanting to study her brain after death

They wanted a biological explanation that would preserve scientific racism—anomalies could be studied, dissected, used to reinforce racist theories.

Not genius.

Not brilliance.

An “abnormality.”

But the Black community refused.

When authorities arrived at Reverend Wilson’s church, dozens of armed Black men stood guard around the building. They made it clear:

No one was taking Sarah.

Federal law, AME influence, and community resistance forced the white officials to back down.

But Harriet understood.

Sarah could never truly be safe in the South.

So, in 1871, at age thirteen, Sarah was sent North—alone—to live with AME affiliates in Philadelphia and study at one of the most prestigious Black institutions in America:

The Institute for Colored Youth.

Harriet stayed behind. Poverty trapped her.

Mother and daughter would never meet again.

Chapter VII: Brilliant, Educated, and Haunted

From 1871–1876, Sarah excelled at the Institute.

She mastered:

—Latin

—French

—advanced mathematics

—history

—science

—classical literature

She stunned teachers with her ability to read a textbook once and know every word. She graduated early, one of the most gifted students the institute had ever seen.

But brilliance came with torment.

Sarah could not forget anything—especially her trauma.

She relived slavery as vividly at sixteen as she had at six. She experienced flashbacks that left her shaking, disoriented, terrified. Today, psychologists would recognize this as PTSD worsened by eidetic recall.

She had no therapy.

No support.

No release.

Every memory—the beatings she witnessed, the threats, the screams—was as sharp as the day it happened.

She lived with trauma that never faded.

And then, at eighteen, Sarah Brown disappeared from history.

Completely.

Chapter VIII: The Vanishing of a Genius

After 1876, there is no record of Sarah.

No marriage certificate.

No death certificate.

No employment records.

No letters after 1879.

There are three leading theories:

1. She died young.

Chronic trauma, poverty, depression—any could have overwhelmed her. Many Black women died of illness or exhaustion before 30, and their deaths often went unrecorded.

2. She changed her name to escape her past.

Trauma survivors often flee their identities.

Black Americans frequently changed names post-emancipation for safety.

Sarah may have chosen anonymity—silencing her gift to survive.

3. She was institutionalized or killed.

A Black woman suffering flashbacks in the 1870s could easily be labeled “insane” and confined.

Or targeted by men she could identify from memory.

Her gift made her dangerous.

And dangerous Black people did not survive long in a society rebuilding white supremacy after Reconstruction.

We will almost certainly never know.

Chapter IX: The Evidence That Survived—Barely

Though Sarah vanished, fragments of her story live on in:

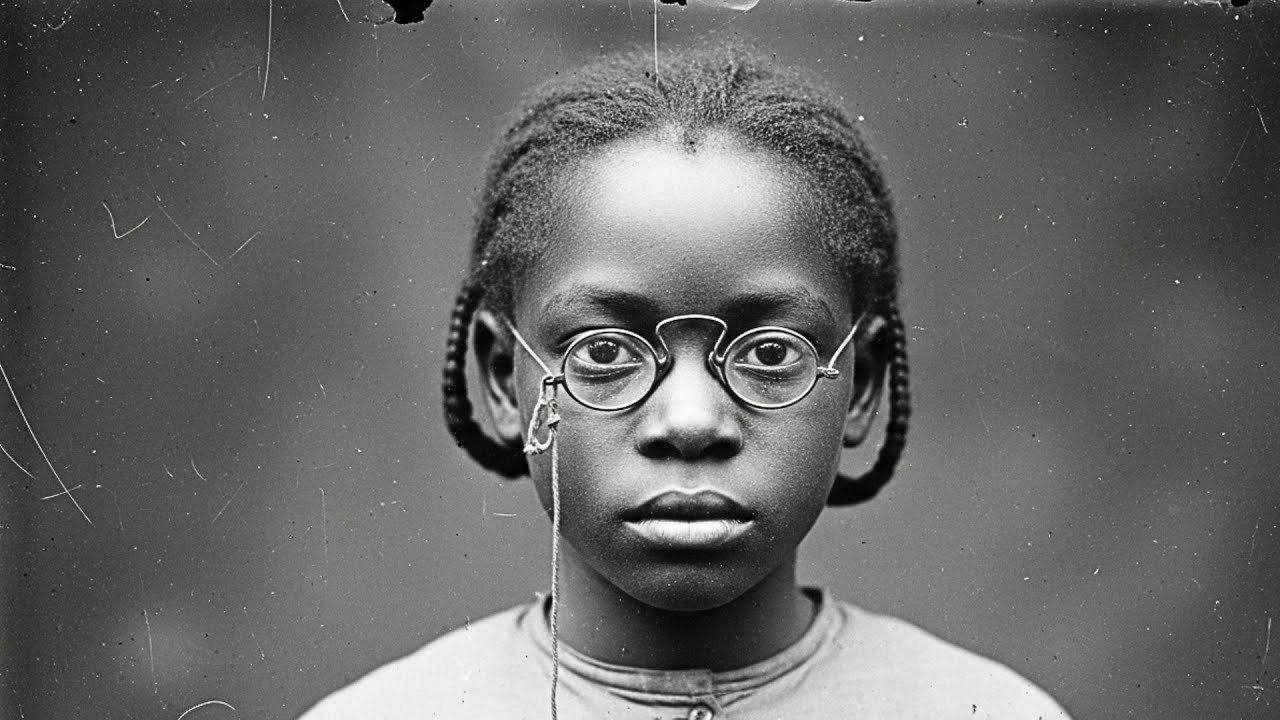

1. A photograph (1866)

A small Black girl, straight-backed, staring into the camera with unnerving intensity.

Labeled only: “Memory Girl, Washington, Georgia.”

2. AME Church letters

Referring to “the Brown girl from Georgia who remembers everything.”

3. Reverend Wilson’s journal

Describing her as a living archive—and her suffering.

4. A letter from Martha Williams (1867)

Which contains perhaps the most haunting summary of all:

“They do not fear the child.

They fear what she remembers.

In a nation desperate to forget its sins,

a girl who cannot forget becomes the greatest threat of all.”

Sarah Brown was not just a prodigy.

She was a witness.

And America has always tried to silence witnesses to its crimes.

Chapter X: Why Her Story Matters Now

Modern neuroscience suggests Sarah truly had photographic memory.

Her documented abilities match rare cases seen today. She could have been:

—a scientist

—a linguist

—a historian

—a mathematician

—a professor

—a world-changing intellect

Instead, she was exploited by white men, endangered by white violence, and ultimately erased.

Not because she lacked potential.

But because she possessed too much of it.

Because she remembered what America needed forgotten.

Because she represented Black brilliance in a society determined to deny it.

Sarah Brown’s life illustrates a chilling truth:

Genius in a Black girl was never seen as a blessing.

Only a threat.

And threats were eliminated.

Epilogue: A Girl Who Remembered Everything, in a Country That Forgot Her

Sarah Brown should be a household name.

She should appear in psychology textbooks, history books, documentaries, classrooms.

She should be recognized as one of the most extraordinary minds ever recorded.

Instead, power erased her.

But fragments survive—just enough for us to rebuild her memory.

And in doing so, we honor her.

Because she spent her life remembering things others wanted forgotten.

Because she carried the history of her people when the world tried to bury it.

Because she embodies not just genius, but the tragic cost of Black brilliance in a country built on suppressing it.

Sarah Brown remembered everything.

And now, at last—

we remember her.

News

Husband Treats Wife Like A Maid On Family Feud! Steve Harvey’s Reaction Shocked Millions Of People | HO!!!!

Husband Treats Wife Like A Maid On Family Feud! Steve Harvey’s Reaction Shocked Millions Of People | HO!!!! Linda blinked…

At 62, Julian Lennon Admits ”I Utterly Hated Her” | HO!!!!

At 62, Julian Lennon Admits ”I Utterly Hated Her” | HO!!!! At sixty-two, Julian Lennon sat under studio lights that…

Woman Takes Steve Harvey ‘s Seat – Then Discovers He… | HO!!!!

Woman Takes Steve Harvey ‘s Seat – Then Discovers He… | HO!!!! The hum of jet engines filled the cabin…

At 41, Doris Day’s Grandson Reveals the Secret She Kept Hidden For Years | HO!!!!

At 41, Doris Day’s Grandson Reveals the Secret She Kept Hidden For Years | HO!!!! Ryan Melcher was forty-one when…

Steve Harvey STOPS Family Feud in Tears When 97 Year Old Guest Reveals She Was His Mom’s Best Friend | HO!!!!

Steve Harvey STOPS Family Feud in Tears When 97 Year Old Guest Reveals She Was His Mom’s Best Friend| HO!!!!…

3 Days After Her Husband Came Out Of Prison, She Divorced Him When She Found Out His 𝐏𝟑𝐧𝐢𝐬 is.. | HO

3 Days After Her Husband Came Out Of Prison, She Divorced Him When She Found Out His 𝐏𝟑𝐧𝐢𝐬 is.. |…

End of content

No more pages to load