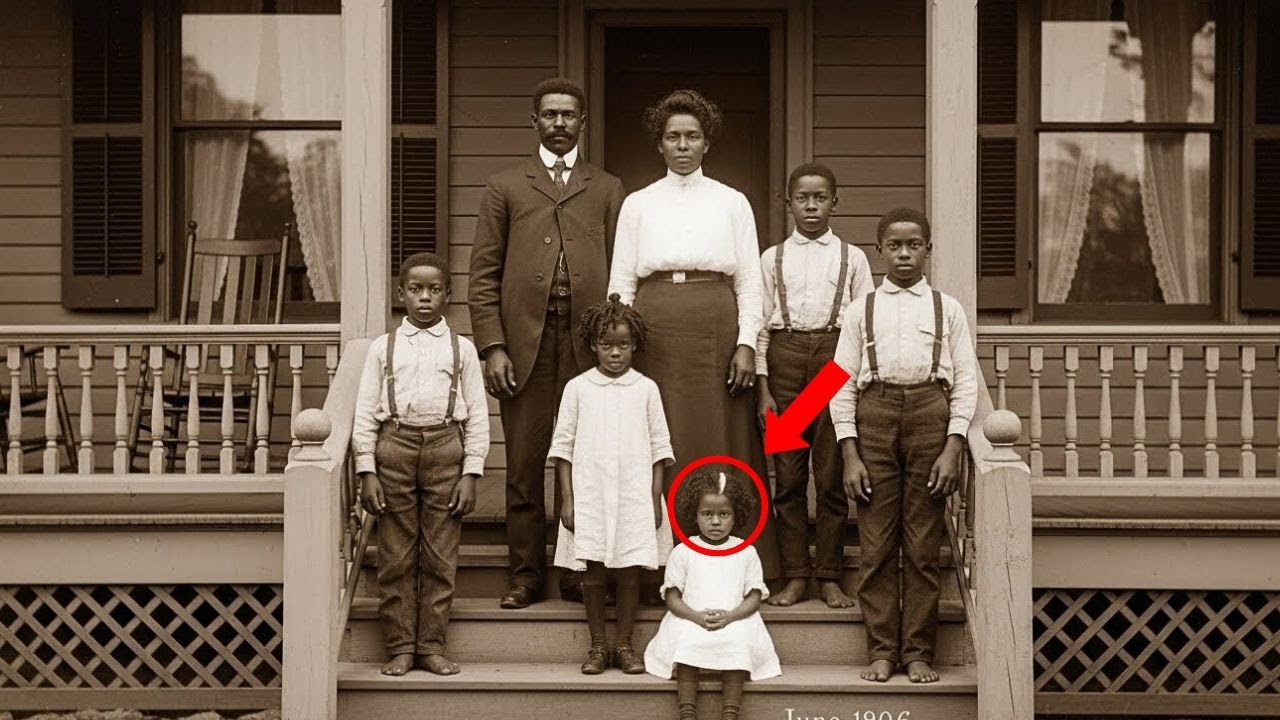

1906 Family Photo Restored — And Experts Freeze When They Zoom In on the Youngest Child’s Face | HO!!

The photograph arrived at Maya Richardson’s Brooklyn studio on a cold January morning, tucked inside a padded envelope, swaddled in acid-free tissue like something that had already survived too much. Her radiator knocked in uneven rhythms, Sinatra hummed softly from an old speaker, and a little U.S. flag magnet clung to the metal edge of her filing cabinet, pinning up a client checklist that read, in block letters, HANDLE ORIGINALS WITH GLOVES.

Maya had restored thousands of images—Civil War tintypes, faded Victorian portraits, water-stained albums rescued from basements—but something about this package made her slow down before she even opened it. The return address said Charleston, South Carolina. The sender: Grace Thompson. The letter inside was brief, almost pleading: This photograph has been in my family for generations. It’s the only image we have of my great-great-grandmother’s family, but it’s badly damaged. I’m told you’re the best at what you do. Please help me see their faces clearly.

The hinged sentence was the first quiet wager the story made: when someone asks you to restore a face, they’re really asking you to restore a missing chapter.

Maya unwrapped the photograph and slid it beneath her magnifying lamp. The image was in rough shape. The emulsion had cracked and peeled in several places, like dried riverbeds. Water damage had left dark stains across the bottom third, and someone long ago had tried a crude repair that only made everything worse—thick smears where details should have been, a kind of desperation pressed into paper.

But beneath the damage, she could still see the ghost of a composition: seven people posed in front of a wooden house with a wide porch. The photograph was mounted on thick cardboard backing, and on the reverse, written in faded pencil, were three words that made her sit up straighter: June 1906, Charleston. Below that, a series of names—some legible, others washed away into faint gray.

She photographed the original with her high-resolution camera, creating a digital master file so her work wouldn’t risk further harm to the fragile artifact. Then she opened her restoration software and began the slow technical surgery: cloning undamaged sections to fill cracks, feathering edges so repairs didn’t look like patches, reducing discoloration from the old failed fix, lifting stains without flattening the texture that made the image real.

Her hand moved across the tablet with practiced confidence. Fifteen years of restoration had taught her the same lesson again and again: the mistake is always impatience.

Three hours in, the structural repair was complete. The porch railings were continuous again. The dark wash along the bottom softened into something that looked like shadow instead of rot. The figures sharpened into a family: a man in a dark suit with a high collar, a woman beside him in a white blouse and long skirt, and five children ranging from a teenager down to a small child sitting on the porch steps.

Maya leaned back, rolled her shoulders, saved the file, and told herself she would start the faces tomorrow. Faces required a different kind of focus, the kind where you don’t just repair what’s missing—you decide what deserves to be seen.

The hinged sentence clicked into place as she shut down for the night: you can fix a photograph in an afternoon, but you can’t control what it will ask you to learn.

She returned the next morning with fresh eyes and the strongest coffee she could justify before noon. Structural restoration was done. Now came the delicate work of pulling people out of haze—recovering the details that made them individuals, not silhouettes.

She started with the adults, enhancing contrast and sharpness until the man’s jawline came through and the tension in his mouth became visible. Mid-30s, serious, shoulders squared as if even a camera demanded discipline. His hand rested on the woman’s shoulder, a gesture that read as protection and partnership at the same time, the way families posed when they wanted the world to believe they were solid.

The woman’s face emerged next—intelligent, determined, gaze direct. Maya found herself imagining exhaustion behind that posture: managing a household and five children in 1906 Charleston, holding herself upright anyway because the world was always watching and never forgiving.

Then the children. A teenage boy about fifteen stood near his father, nearly as tall, his expression caught between pride and the discomfort of being told not to move. Two girls around twelve and ten, hair braided with white ribbons, mouths pressed into polite lines. A boy about seven with a grin that wouldn’t behave, missing a front tooth as if even formality couldn’t erase childhood. And finally, the youngest: a little girl sitting on the porch steps, hands folded in her lap.

The damage there was worst. A large water stain obscured most of her face. Maya worked slowly, layer by layer—lifting discoloration without inventing features, coaxing detail from what remained. As the child’s face began to emerge, Maya paused with her stylus hovering above the screen.

Something wasn’t just unusual. It was… specific.

She increased magnification, focusing on the eyes and forehead. Her breath caught. Even accounting for grain, even accepting the limitations of early camera technology, what she was seeing didn’t fit the tidy assumptions people make about old photographs. The spacing around the eyes looked distinctive. And there—near the crown—what looked like a lighter patch in the hair that wasn’t glare, wasn’t damage, wasn’t a restoration artifact.

Maya sat back, heart tapping faster than it should for a Tuesday morning in a quiet studio. She’d restored every kind of face genetics could produce. But this felt like something with a name, something clinical—except the year in pencil said 1906.

She picked up her phone and called Dr. James Wright, a colleague who taught medical history at Columbia and had helped her before when old images hinted at conditions the past never documented properly.

James answered on the second ring. “Maya?”

“I need you to look at something,” she said, keeping her voice even even as her mind ran. “I’m working on a photograph dated June 1906, Charleston. I think I’m seeing signs of a genetic condition in a child’s face. If I’m right, it wasn’t even identified until the 1950s.”

A pause. Then, “Send me a screenshot. And don’t touch the face any more than you have to.”

The hinged sentence arrived like a cold draft through a closed window: when a detail refuses to be explained by damage, it’s usually because it’s the truth.

Dr. James Wright arrived that afternoon, tall and silver-haired, the gentle manner of someone who had spent decades teaching students that the body carries history in plain sight. Maya had the image displayed on her large monitor, zoomed tightly on the youngest child’s face.

James leaned in, studying silently. Maya watched his expression change from casual interest to focused attention, then to something like astonishment.

“You’re seeing what I’m seeing?” Maya asked, quietly, as if volume could disturb the past.

James nodded slowly. “If this photograph is authentic and unaltered—and I assume you’ve verified that—then yes. I’m seeing clear markers of Waardenburg syndrome.”

Maya exhaled, like she’d been holding breath for hours without noticing. “But that wasn’t—”

“It wasn’t named until 1951,” James said, finishing the thought. “Named isn’t the same as existing.”

He pointed carefully, narrating as if teaching a class. “Look at the distance between the inner corners of the eyes. Dystopia canthorum.” He traced the screen without touching it. “And here—this lighter patch in her hair. That could be a characteristic white forelock.”

Then he paused at the child’s eyes, and Maya leaned closer with him. Even through grain, even with the last imperfections of restoration, the difference was visible. One eye appeared darker, consistent with deep brown. The other looked distinctly lighter—pale blue or gray, startling in contrast.

“Heterochromia,” James said softly. “Complete heterochromia iridis. Different colored eyes. Combined with the other features, it’s almost certainly Waardenburg syndrome type one.”

Maya felt a chill run up her arms that had nothing to do with winter. “So… in 1906 Charleston,” she said, voice careful, “how would people have understood this?”

James didn’t answer immediately. “They wouldn’t have,” he said finally. “Some might have assumed partial albinism. Some would have made stories about ancestry. Some would have been afraid. Others might have called her blessed or cursed, depending on their beliefs.” He glanced at Maya. “For a Black child in segregated South Carolina, looking this different in a way people couldn’t explain… it could have been complicated. Potentially dangerous.”

Maya stared at the child’s face—the small, serious mouth, the posture that looked too composed for someone so young. It struck her how easily a camera could capture what a community might spend years arguing about.

She pulled up Grace Thompson’s letter again on her screen. “Grace says this is her great-great-grandmother’s family,” Maya said. “She wants to see their faces clearly. Should I tell her what we found?”

James didn’t hesitate. “Yes,” he said firmly. “It’s part of her family’s story. And honestly? It’s historically significant. Conditions like this existed long before medicine gave them names. Your restoration didn’t create it—it revealed it.”

Maya nodded, then returned to the work with a new kind of care. She finished restoring the child’s face without exaggeration, letting the features speak for themselves. When she printed the restored photograph, the youngest child was no longer a stained blur. She was present: wide-set eyes, a visible difference in color, a pale streak in dark hair, expression steady.

Maya wrote Grace an email and chose every word like she was handling the original again: she explained the restoration was complete, and that the youngest child displayed physical characteristics consistent with Waardenburg syndrome, a condition affecting pigmentation and facial structure that wasn’t medically identified until 1951. She explained this meant the family in 1906 would not have had language for what made the child different, but that the difference itself was real and could be important context for family history.

She hesitated before hitting send—because you don’t know how a stranger will feel when you hand them a truth wrapped in science. Then she remembered Grace’s line: Please help me see their faces clearly. Maya clicked send and packaged the restored print.

The hinged sentence sat in her throat as the box sealed shut: the past doesn’t ask your permission to be complicated—it only asks to be seen.

Three days later, her phone rang. Charleston area code. Maya answered and heard a woman’s voice that sounded warm but strained, as if she’d been holding emotion back for hours.

“Ms. Richardson? This is Grace Thompson. I got your email. I’ve been staring at the restored photograph for two days.”

Maya’s hand tightened around the phone. “I’m glad it reached you safely.”

Grace took a breath. “The little girl,” she said, and her voice softened. “The one with the different-colored eyes. That’s my great-great-grandmother. Her name was Sarah.”

Maya’s heart skipped, the way it does when a face becomes a life. “So she—she grew up.”

“That’s why I’m calling,” Grace said. “After I read your email, I went through everything I have. Old letters. Bible records. Newspaper clippings my grandmother saved. I’ve been trying to piece Sarah’s story together for years, but there are gaps. My grandmother barely talked about her own grandmother, and when she did, she was vague.” Grace paused. “Now I think I understand why.”

“What did you find?” Maya asked.

“I found a letter from 1924,” Grace said. “Sarah wrote it to her daughter—my great-grandmother. In it, she talks about being different all her life. About people treating her with fear or fascination. She mentions a woman named Clara who protected her as a child and taught her everything. I never understood what that meant before, but now… now you tell me Sarah had Waardenburg syndrome.”

Maya finished the thought quietly. “And in 1906 Charleston, that would have made her vulnerable.”

“Exactly,” Grace said, voice tightening. “Ms. Richardson, would you help me find out more? About Sarah, about Clara, about what Sarah’s life was really like? I have pieces, but I can’t fit them together.”

Maya looked back at the restored 1906 photograph on her monitor. The youngest child sat on porch steps like she’d been waiting for someone to finally notice her properly.

“Yes,” Maya said. “I’ll help.”

Two weeks later, Maya stood in the arrivals area of Charleston International Airport holding a sign with Grace Thompson’s name. She had decided this story was too important to research from Brooklyn. Grace emerged from the crowd—early fifties, warm eyes, high cheekbones that looked like they’d traveled through the generations without losing shape. They recognized each other immediately, and Grace hugged her with the relief of someone who’d been carrying questions alone.

“Thank you for coming,” Grace said. “I know you didn’t have to. Restoring the photograph was your job. This is something more.”

“This is history,” Maya replied. “And I want to help you find it.”

They drove into Charleston under golden afternoon light, past historic homes and live oaks draped with Spanish moss. Grace pointed out landmarks as they passed: the old slave mart museum, Mother Emanuel AME Church, neighborhoods that had been the heart of Black Charleston in the early twentieth century.

“The house in the photograph doesn’t exist anymore,” Grace said. “Torn down in the ’50s during urban renewal. But I know the street it was on.”

Grace’s home was a modest bungalow in North Charleston filled with family photos spanning five generations. Her dining room had been turned into a research center: a table covered in neatly organized stacks of documents, a laptop, a whiteboard crowded with notes and a hand-drawn family tree.

“I’ve been working on this for three years,” Grace said, gesturing to the organized chaos. “Ever since my mother died and I inherited the papers she kept.”

She brought out letters tied with ribbon. “These are from Sarah. She wrote to my great-grandmother—her daughter—between 1924 and 1948. Sarah died in 1952 when my grandmother was a teenager. My grandmother said Sarah got quiet in her later years. Like she was tired of remembering.”

Maya held the letters carefully. The handwriting was clear, educated, each one dated with care. Then Grace pulled out another item: a small leatherbound book with a broken clasp.

“This is what made me reach out to you,” Grace said. “It’s a journal written by someone named Clara Bennett. It covers 1902 to 1928. Sarah is mentioned throughout. But it’s not just a diary. It’s medical observations, treatments, records of births and deaths. I think Clara was a midwife or healer.”

Maya opened the journal and found neat, precise entries. An August 1906 note made her throat tighten: Sarah continues to thrive despite the talk among some families. Her eyes and hair make her a curiosity, but she is bright and quick to learn. I have convinced her mother to keep her close to home until she is older and stronger. The world is not always kind to those who are different.

Maya looked up. “Clara knew,” she said.

Grace nodded, eyes wet. “From the beginning.”

The hinged sentence landed as the room filled with the weight of paper and time: sometimes the first person to understand a child isn’t a doctor—it’s the woman who shows up when everyone else whispers.

They spent the evening reading Clara Bennett’s journal aloud, taking notes. A picture formed of a remarkable woman who served Charleston’s Black community as a healer, midwife, and informal physician for nearly three decades. Clara was born in 1870, daughter of formerly enslaved people who had learned herbal medicine and midwifery during slavery and passed that knowledge down. By 1902, Clara was thirty-two, trusted with births, illnesses, deaths.

The first mention of Sarah appeared in June 1906, the same month as the photograph: Delivered Ruth’s fifth child today, a girl they named Sarah. The birth was straightforward, but the child’s appearance is unusual. Her eyes are two different colors, one dark like her parents, one pale blue like I have never seen in a colored child. There is also a white streak in her hair at the crown. Ruth is frightened, wondering if her baby is cursed. I assured her the child is healthy and whole, just different. I have read of such things in my medical books, though I do not have a name for this particular condition.

“Ruth,” Maya said softly, “that must be Sarah’s mother.”

Grace traced the page with her fingertip. “Clara was there the day she was born,” she whispered.

The entries continued—Sarah meeting milestones, Clara noting how she responded to sound and voices, how she crawled, how she learned quickly. But Clara also recorded the community’s reactions: rumors, superstition, fear. Ruth keeps Sarah mostly at home, which is wise for now, but cannot last forever.

By 1908, Clara wrote: I have offered to help educate Sarah when she is older. Ruth is grateful but worried about how people will react if her daughter learns too much. I reminded her that knowledge is the best protection we can give our children, especially children who will face extra scrutiny for being different.

Maya noticed Clara returned to Sarah again and again with a personal investment that went beyond clinical observation. This wasn’t just documentation. This was protection written in ink.

Grace pulled out a faded clipping from the Charleston Messenger, a Black-owned newspaper from the early twentieth century. It was dated 1925 and featured a young woman in a nurse’s uniform.

Local Woman Completes Nursing Training.

Maya compared the face in the clipping to the restored 1906 portrait. The distinctive spacing, the direct gaze. The eyes weren’t as visible in the newspaper reproduction, but the person was unmistakable.

“That’s Sarah,” Grace said, voice rising with awe. “She became a nurse. In 1925. In South Carolina.”

The next morning they went to the Charleston County Public Library archives. Grace requested files on Clara Bennett, nursing schools in the 1920s, and records from the neighborhood where Sarah’s family lived. The librarian, Frederick, an older man who’d worked archives for forty years, greeted Grace like he’d seen her in these rooms before.

When Grace explained what they were researching, Frederick’s expression shifted to recognition. “Clara Bennett,” he said slowly. “I know that name. My grandmother talked about a healer named Clara who delivered half the babies in the neighborhood. Said she was the smartest person she ever knew. Taught herself medicine from books when no school would admit her.”

He disappeared into back rooms and returned with boxes. “These are records from the Cannon Street Hospital and Training School for Nurses. One of the few institutions training Black nurses in the 1920s. If Sarah trained, she might be here.”

They flipped through admission rosters, training lists, graduation records. Hours passed in quiet concentration until Grace’s breath caught.

“There,” she said, pointing. Her finger trembled slightly.

Maya read aloud: Sarah admitted September 1922, sponsored by Clara Bennett, graduated May 1925 with honors, special commendation for dedication to patient care.

“Sponsored by Clara Bennett,” Maya repeated.

Grace swallowed hard. “Clara didn’t just protect her,” Grace said. “She made it possible.”

They found Clara’s journal entry from 1922: Sarah has been accepted to the nursing school. I used every contact and favor I have accumulated over 30 years to make this happen. The administrators were hesitant. Sarah’s appearance makes her memorable and not always in comfortable ways. But her intelligence and determination won them over. She will face challenges there that other students will not face. People will stare at her eyes, whisper about her difference. But Sarah has lived her whole life being stared at. She knows how to meet the world with dignity.

Frederick brought employment records from the Charleston County Health Department. “They started hiring Black nurses in the mid-1920s for home visits in colored communities,” he explained. “If she worked here after graduation, there might be something.”

There was. Sarah, registered nurse, assigned to home visits in the East Side community. Monthly salary: $45.

Frederick unfolded a map from the 1920s and pointed to the East Side. “That was rough territory,” he said. “Overcrowding. Poor sanitation. Limited access to care. The nurses who worked there… they walked into homes where they might find anything.”

Grace found a letter from Sarah dated 1927, written to her daughter. It read: I visit families today who look at me with suspicion at first. My eyes make them uncertain. But when I help deliver a healthy baby or treat a child’s fever or show a mother how to keep her family well, they forget about my difference. They see me as someone who cares. Clara taught me that the best way to overcome prejudice is to be undeniably good at what you do.

The hinged sentence arrived as Maya watched Grace fold the letter back into its ribbon: the world may stare first, but skill is a language even prejudice has trouble arguing with.

On their third day in Charleston, Grace took Maya to the cemetery where Sarah was buried, a small, well-kept African-American cemetery with graves dating back to the late 1800s. Sarah’s headstone was simple: Sarah, 1906–1952, beloved mother, grandmother, and healer. They stood in silence long enough for the city noise to feel far away.

Then Grace reached into her bag and removed a small wooden box. Inside, wrapped in soft cloth, was a tarnished silver pin shaped like a nurse’s cap.

“This was Sarah’s nursing pin,” Grace said. “My grandmother gave it to me before she died. She said Sarah wore it every day she worked, even after it went out of style. She said it reminded her what she had to overcome to earn it.”

Maya photographed the pin carefully, adding it to their documentation. As she adjusted focus, an elderly woman approached with a cane, moving slowly but with purpose. She looked at the headstone, then at Grace.

“You Sarah’s family?” the woman asked.

Grace nodded. “Her great-granddaughter.”

The woman’s face softened. “Sarah delivered me,” she said with a gentle smile. “December 1949. I was born two months early. The doctors said I wouldn’t make it. But Sarah came to our house every day for six weeks. Taught my mama how to care for a premature baby.” She tapped her cane once, as if to underline the fact. “She saved my life.”

Her name was Dorothy. She was seventy-four. She’d lived her whole life in Charleston and still remembered Sarah’s visits to the neighborhood in the late ’40s and early ’50s.

“People called her the nurse with angel eyes,” Dorothy said. “Because one eye was light like heaven, or that’s what folks said. She was patient. She’d sit with families for hours, making sure they understood.”

Dorothy’s gaze drifted to the headstone. “But she was sad sometimes. My mama said Sarah lived through things that would’ve broken most people.”

Maya asked if Dorothy would be willing to be interviewed on camera. Dorothy nodded immediately. “Her story should be told,” she said. “People forget. Young folks need to know what it took for somebody like Sarah to survive and still give.”

That evening, in Grace’s living room, Dorothy spoke into Maya’s camera about Sarah’s competence, the medicine bag she carried, the way she explained health in terms families understood. Maya spent the next two days collecting more oral history. The pattern was consistent: Sarah was unusual in appearance, remarkable in character. Her difference became a kind of strength.

One ninety-one-year-old man, Robert, said, “My mama told me administrators said her appearance would make patients uncomfortable.” He shook his head. “But once people met Sarah, once they saw how good she was, they forgot about her eyes. They saw her care.”

Another woman showed photos from a 1948 community health fair: Sarah at a table covered in educational materials, surrounded by mothers listening intently. Her distinctive eyes were visible, but what struck Maya was her posture—confident, direct, completely at home in her role.

Records showed Sarah worked until six months before her death in 1952. She was forty-six when she died; the death certificate listed heart failure. Clara’s journal, ending in 1928, included notes about Sarah pushing herself too hard, neglecting her own well-being while caring for others.

The last puzzle piece arrived from Grace’s cousin in Columbia, South Carolina, who sent a box of letters Sarah wrote to her daughter in the 1940s while the daughter was away at college. These were intimate and revealing: the challenges of being a Black nurse in a segregated system, the weight of responsibility, and the quieter pain of childhood.

In a 1946 letter, Sarah wrote: I want you to understand something about being different, about having people stare and whisper. When I was young, Clara taught me that difference can be either a burden or a gift, depending on how you choose to carry it. I chose to let it make me more compassionate, more determined to help others who also feel like outsiders. My eyes that made people uncomfortable as a child became my trademark as a nurse. People remembered me, trusted me, knew I would come when they needed help. The very thing that could have limited me became part of my strength.

Grace read that letter aloud on camera, her voice breaking on the last line. Maya didn’t speak; she didn’t need to. The words did what history rarely does: they explained themselves.

The hinged sentence that closed the circle of Sarah’s voice was the one the past had been trying to say all along: the thing that makes you conspicuous can also make you unforgettable in the best way.

On Maya’s last evening in Charleston, she and Grace built a timeline across the dining room table—dates, documents, photos, testimonies, names braided together until the story stopped feeling like a mystery and started feeling like a life. A child born with Waardenburg syndrome in 1906 South Carolina, raised under segregation, protected and educated by a healer, trained as a nurse despite visible difference, dedicating her career to caring for the most vulnerable.

Three months after Maya returned to Brooklyn, she stood in the Charleston Museum at an opening reception for an exhibition titled Hidden Faces, Revealed Lives: The Story of Sarah and Clara Bennett. The restored 1906 family photograph held the central position, enlarged so visitors could see every face clearly—especially the youngest child on the porch steps. Beside it, Clara’s journal sat open to the entry describing Sarah’s birth. Across from that, Sarah’s 1946 letter hung on the wall, her words printed in clean black type.

And in a glass display case, resting on dark velvet, was the tarnished silver nursing pin—no longer just an object in a box, but a symbol with a plaque beneath it: Sarah’s graduation pin, 1925.

Dr. James Wright had contributed a medical panel explaining Waardenburg syndrome, its genetic basis, and why it wouldn’t be identified until 1951. He emphasized what mattered most: the condition affected appearance, not intelligence or capability, and throughout history people with it were often misunderstood—feared, romanticized, pushed aside—depending on who was doing the looking.

The exhibition honored Clara Bennett, too. Research revealed Clara delivered more than **800** babies, trained dozens of women in midwifery and herbal medicine, and quietly challenged a medical establishment that denied Black women formal training by proving skill could exist without permission.

A local filmmaker approached Grace about a documentary. A medical historian from Duke asked about including Sarah in a book. A nursing school expressed interest in creating a scholarship in Sarah’s name.

Dorothy stood before the photograph with tears streaming down her face. “I have lived seventy-four years because of her,” she told anyone near enough to hear. “She came every single day when I was too small, too early. Not because we had money—we didn’t—but because she believed every child deserved a chance.”

Grace spoke at the microphone near the end of the evening. “When I sent that damaged photograph to Maya for restoration, I just wanted to see my ancestors’ faces clearly,” she said. “I never imagined what we would discover. For generations, we knew Sarah was a nurse, but we didn’t know her full story. We didn’t know about Clara who protected and educated her. We didn’t know about the genetic condition that made her different, or how she transformed that difference into strength.”

Grace looked at the enlarged portrait of four-year-old Sarah—serious, steady, unmistakable. “Sarah grew up when being different was dangerous. She did it anyway, supported by people who saw her worth. This honors not just Sarah, but all the people in our communities whose remarkable lives were quiet, whose stories deserve to be remembered.”

Maya watched visitors move through the exhibit, pausing to read, leaning close to study faces, murmuring when they saw Sarah’s eyes. She thought back to the first moment she zoomed in on the child’s face and felt her breath catch. The shock wasn’t really that the condition existed in 1906; the shock was realizing how much of history is visible if you know how to look, and how much gets forgotten when nobody bothers to ask what a face has been carrying.

Before the museum closed, Maya stood again in front of the restored photograph. It was no longer a damaged artifact begging for repair. It was a window. It was proof that a community saw a child who was different and made choices—some fearful, some superstitious, and one crucially protective. Clara had chosen protection. Sarah had chosen purpose.

Grace came up beside her, voice quiet. “Thank you,” she said. “For seeing what was hidden. For caring enough to help me find the truth.”

Maya turned toward the display case where the tarnished silver nursing pin sat under museum light, no longer tucked away in family cloth. “Thank you for trusting me with it,” Maya said. “There are probably thousands of stories like Sarah’s, waiting in damaged photographs and forgotten documents.”

As Maya flew back to Brooklyn the next day, she thought about the stack of new restoration requests waiting in her inbox—families wanting to see faces clearly, wanting time to give something back. She wondered how many other hidden lives were waiting behind stains and cracks. How many other children on porch steps were still misunderstood by history because nobody zoomed in long enough.

Now, generations would see Sarah the way she deserved to be seen: not as a curiosity, not as a rumor, but as a nurse, a healer, a woman whose difference became a signature of care. The restored 1906 photograph would hang in Charleston, and the story behind the youngest child’s face would travel—through museum halls, through documentaries, through scholarships, through family conversations where the past finally had the right words.

The final hinged sentence settled in Maya’s mind as the plane lifted off: every photograph is a door, and sometimes restoration is just the act of turning the handle.

News

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!…

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!…

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!…

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!!

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!! Sometimes death is…

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI Came | HO!!

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI…

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!!

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!! Xavier was the kind of…

End of content

No more pages to load