1935 News: Dutch Schultz’s Racial Insult to Bumpy Johnson — 8 Men Dead in a Week | HO!!!!

An Investigative Report into the Harlem Blood Message That Rewrote Underworld Power

Harlem, September 1935. The Cotton Club—smoke-filled, champagne-slick, pulsing with Duke Ellington’s horns and the clipped laughter of the downtown elite—had seen its share of theatrics. But on the night of September 16, 1935, the drama did not unfold onstage.

It unfolded at a back table.

There, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson, the soft-spoken strategist who quietly ran Harlem’s most sophisticated policy network, sat alone—watching, listening, calculating. He carried himself with the stillness of a chessmaster considering the long board.

Moments later, Arthur Flegenheimer, known to every bootlegger and bookmaker in America as Dutch Schultz, rose from his table near the stage—flushed with whiskey and supremacy—and began marching toward Johnson. Schultz’s reputation was legend: volatile, fabulously wealthy, and accustomed to owning both territory and men through intimidation. The crowd sensed trouble the way sailors sense weather. Heads turned. Conversation died.

Schultz slammed his hand down on Johnson’s table. The bourbon glass jumped. Then, in a voice loud enough to suffocate the music and freeze 200 patrons in place, he delivered a tirade so racially venomous that even in Jim Crow-era New York, the room recoiled. He called Johnson “boy.” He said Harlem’s Black policy operators were tolerated guests in a white racket. He branded them incompetent. Disposable.

No one breathed.

Bumpy Johnson never raised his voice.

Never reached for the .45 he was rumored to carry.

He simply looked up—cold, unreadable—and said:

“You’ve got seven days to get your people out of Harlem.

After that, any white man I find running policy in my neighborhood dies.”

Schultz laughed—the booming laugh of a man who believed the laws of power bent permanently in his favor. He mocked the warning. He taunted the room.

Johnson stood, finished his drink, and walked into the Harlem night.

By sunrise, the first body would be found.

By week’s end, eight white gangsters would be dead.

And a principle would be written, permanently, into the criminal code of New York City:

Disrespect Harlem at your own risk.

I. Setting the Stage — Control, Territory, and Humiliation

To understand the shock that followed, one must understand what Dutch Schultz thought he owned.

By 1935, Schultz had built a $20-million empire through bootlegging, gambling, and political protection rackets. When Prohibition ended, he pivoted to the policy game—the informal daily lottery that flowed through Black neighborhoods, long before state governments legalized and captured its profits.

Policy wasn’t just gambling. It was infrastructure. It supported families, funded funeral costs, paid rent when work dried up. It also created Black economic autonomy at a time when nearly every other financial path was blocked.

Schultz intended to seize it.

He brought money, political muscle, and firepower. What he did not bring was respect. To him, Harlem operators—Madame Stephanie St. Clair, Casper Holstein, and Bumpy Johnson—were not competitors.

They were subjects.

For 18 months, Schultz strong-armed his way into Harlem, installing white collectors and enforcers who treated residents with open contempt. He misunderstood something fundamental:

Policy only works when the community trusts the banker.

Schultz thought he controlled Harlem because he controlled violence.

Harlem merely tolerated him because it lacked options.

Until the Cotton Club.

Until the insult.

Until one man decided that humiliation had a price.

II. The Man Schultz Underestimated

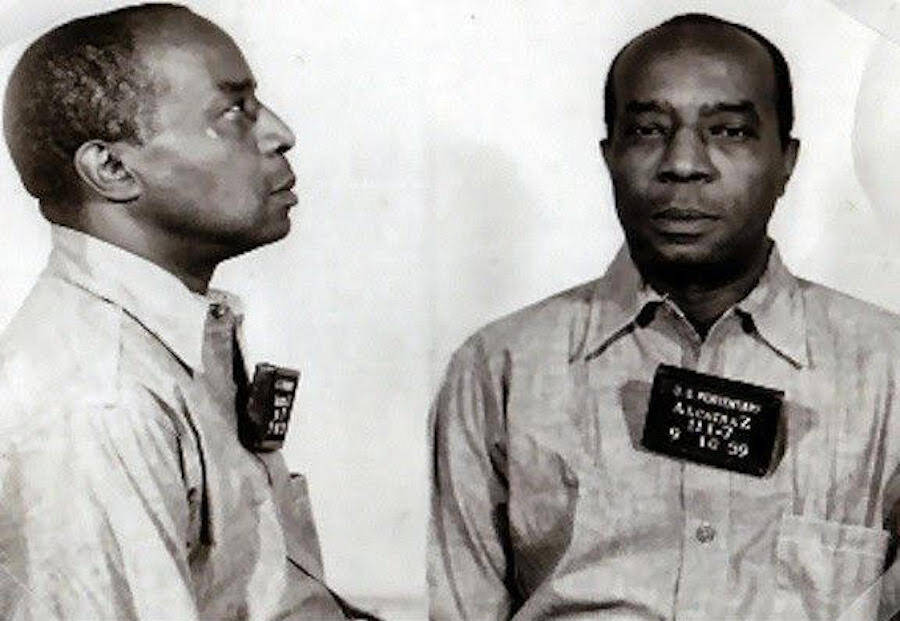

Popular imagination later cast Bumpy Johnson as part-folk hero, part-gang boss, part-tactician. But in 1935 he was largely invisible, and that invisibility was strategic.

He read constantly—philosophy, history, chess theory. He understood power as structure, not spectacle. Where Schultz saw Harlem as a colony to be harvested, Johnson saw a delicate ecosystem held together by reputation and reciprocity.

And Johnson understood something else:

The Cotton Club confrontation was no longer business.

It was a referendum on whether a white gangster could racially degrade a Black gangster, in Harlem, without consequence.

If Bumpy Johnson did nothing, Harlem’s criminal economy—and by extension Harlem’s dignity—would be permanently subordinate. If he struck back, he would be declaring a new rule:

Respect is enforced. Even here. Even now.

So he chose.

Quietly.

Precisely.

Without speeches.

III. Silence as Strategy

When Johnson left the Cotton Club, he did not rally troops or roar threats through Harlem’s nightlife. He vanished.

Policy banks closed.

Associates disappeared.

Phones went unanswered.

To Schultz, this looked like surrender.

It was camouflage.

From a safe location—known only to his tightest circle—Johnson issued an order that blended ruthlessness with icy operational logic:

Eight men.

Seven days.

One per day.

Not Schultz himself.

His infrastructure.

Collectors.

Enforcers.

Policy bankers.

The men who made Schultz’s Harlem operation breathe.

Each death would carry a note.

Each note would count down.

Each body would be found quickly.

The goal was not disorganized retaliation.

It was terror—weaponized with discipline.

And above all, it was message delivery.

A message so indelible, it would echo through the underworld for generations:

Harlem is not a colony.

IV. Body One — The Drum Behind West 145th

Six hours after the Cotton Club humiliation, Vincent “Clutch” Mel—a trusted Schultz collector—finished his nightly rounds. He carried roughly $4,000 in cash and hundreds of betting slips.

He never delivered them.

Intercepted. Abducted. Taken to a warehouse Johnson’s organization controlled.

What happened next was not improvised.

It was ritual, calibrated violence, the kind designed to teach rather than merely kill. Hands broken—symbolic punishment for the collector who handled Harlem’s money. Ice-pick wounds—non-fatal at first, meant to draw time out into horror.

By dawn, Mel’s body lay stuffed inside a metal garbage drum in an alley off West 145th Street.

Pinned to his shirt:

“One down. Seven to go. Leave Harlem.”

Sanitation workers found the drum at 6:23 a.m.

Police saw the message.

Schultz saw the war.

And Harlem saw something else:

A counter-power had awakened.

pasted

V. Police and the Press — A War Without Witnesses

New York detectives, hardened by Depression-era brutality, understood gangland theater. But this was different.

Eight premeditated murders in a week implied logistics, intelligence, and community cover.

Yet Harlem closed ranks.

Schultz’s men asked questions.

Doors stayed shut.

Information dried up.

Because this wasn’t merely crime.

It was retribution layered over racial dignity.

Many Harlem residents despised the policy racket. But they despised Schultz’s contempt more.

So the first murder did what Johnson intended:

It turned Harlem into hostile terrain—not against the police, but against Schultz.

And Schultz—furious, humiliated, unaccustomed to being refused—panicked.

He tripled security.

He shouted.

He threatened.

He threw money around.

But he could not buy something Johnson already possessed:

Harlem’s quiet cooperation.

VI. Body Two — Execution on Lenox

The next day, right on schedule:

Raymond “Red” Sullivan—another Schultz collector—was found in an abandoned Lenox Avenue building. Shot execution-style. Two bodyguards lay dead beside him, their recent gunfight evidence of a brief, futile attempt at protection.

Pinned to the corpse:

“Two down. Six to go.”

This was not frenzy.

It was mathematics.

And New York understood.

Schultz now faced the worst scenario a mob boss can imagine:

A disciplined adversary he could not find,

backed by a community he could not control.

PART 2 — “Seven Days. Eight Bodies. One Message.”

The second body was not a surprise.

The timing was.

Just before dawn, on the second day, Harlem woke to the news that another of Dutch Schultz’s policy collectors had been found dead—this time on Lenox Avenue—shot twice, clean, professional. Forensic examiners confirmed what the street already knew:

This wasn’t random crime.

This was calculated removal.

Pinned to the corpse was a note identical in its spare cruelty to the first:

“Two down. Six to go. Leave Harlem.”

Silence fell over Harlem like winter.

Even people who said little, said nothing now.

Because everyone understood—without explanation—that Bumpy Johnson had made a promise in the Cotton Club, and Harlem’s underground was now watching him keep it.

This wasn’t rage.

It was policy.

I. Schultz Begins to Crack

Dutch Schultz was many things—bold, ruthless, fearless when money was at stake. But beneath the bravado lived a deep paranoia that Prohibition-era violence had carved into him.

Two bodies in two days did not merely anger him.

They mortified him.

He saw the logic.

He saw the countdown.

He saw that he had been placed on a schedule of humiliation.

Worse, he could not hit back.

Because how do you strike a man you cannot find—

—protected by a neighborhood you do not understand

—and who has nothing to lose except the one thing he defends:

Harlem itself.

So Schultz did the only thing men like him ever truly know how to do.

He escalated.

He put a bounty on Bumpy Johnson.

He ordered Harlem collectors to travel in convoys.

He brought in more guns, more muscle, more white faces who walked through Harlem as if their presence itself were power.

It was a fatal misreading of the moment.

Because Harlem was not afraid of more men.

Harlem was now watching one man redefine the rules.

II. Body Three — The Screwdriver Signature

On the third day, a known Schultz associate turned up inside a tenement stairwell, slumped against the wall. His death, again, was clinical. Fast. Deliberate. A folded slip of paper rested inside his coat pocket.

“Three down. Five to go.”

And beside him on the floor lay a screwdriver.

No one needed it explained.

The message was layered:

• You can add guards.

• You can move locations.

• You can shout and threaten and wave guns.

It will not matter.

Because the threat was not about overwhelming firepower.

It was about precision.

By now, the police did what police always do when gangland violence becomes hard to ignore: they blamed “underworld rivalries,” raided a handful of Harlem policy spots, held press briefings, and publicly insisted that control was imminent.

Privately, detectives admitted something else:

The eight-body campaign might actually be real.

And that terrified them too—because if one man in Harlem could declare a rule and enforce it flawlessly, then the balance of power in New York City would never look the same again.

III. The City Watches — But Harlem Watches Closer

Schultz had always believed Harlem tolerated him.

The truth was more cutting.

Harlem endured him.

Policy, for all its moral messiness, had been a Black-run financial ecosystem before Schultz forced his way in. It funded rent, burials, groceries, small comforts. And yes—like all cash economies—it carried vice, corruption, danger.

But it belonged to Harlem.

Schultz turned it into extraction.

So when the bodies began to fall, Harlem did not cheer.

That would be too simple.

But Harlem did not mourn either.

People went quiet.

They minded their business.

They looked away when Schultz’s men asked questions.

And that silence—that deep, impenetrable silence—became Bumpy Johnson’s strongest ally.

You cannot retaliate against an enemy you cannot find.

And you cannot find him in a neighborhood that has already decided you no longer deserve to know anything.

IV. Body Four — “This is the Middle”

Day four broke with rain.

The fourth Schultz man—an enforcer known for spectacular cruelty—was found in a parked sedan a few blocks from the St. Nicholas Houses.

No theatrics.

No spectacle.

Just another folded note, so calm in tone it chilled the detectives who read it:

“Four down. Four to go. This is the middle.”

The middle.

It was a word chosen with surgical care.

It said to Schultz:

You are not dealing with a man reacting emotionally.

You are dealing with a strategist who planned this from the beginning

—and who is not rushing.

The note might as well have been signed,

“Respectfully, Bumpy.”

V. Schultz Considers the Unthinkable

By the fourth death, Dutch Schultz made a decision that stunned even his own crew:

He considered apologizing.

Not publicly. Never publicly.

But the Cotton Club insult now stalked him—not because he regretted it, but because it had triggered consequences he could not stop.

To apologize meant surrender.

To refuse meant bleed.

He saw no third option.

So he did what powerful men always do when cornered:

He lied to himself.

He told himself the killings would taper off.

He told himself Johnson would lose discipline.

He told himself the countdown was bluff.

Anything to preserve the fiction that power still meant immunity.

But Harlem knew better.

Bumpy Johnson always kept count.

VI. Body Five — “You Were Warned”

Day five brought the most high-profile target yet:

A mid-tier Schultz administrator who helped manage the counting houses.

He vanished after lunch.

His body surfaced near the Harlem River that evening.

And although the newspapers spared the public the detail, the detectives who recovered him would later repeat the line pinned to his coat:

“Five down. Three to go. You were warned.”

This was not violence for its own sake.

It was letter-perfect consequence.

Schultz had been warned in a room full of witnesses.

He had responded with ridicule.

Now, every corpse served as documentation.

VII. Body Six — The Hotel Lesson

On the sixth day, a Schultz courier checked into a small Harlem hotel under a false name.

He was found in his room before dawn.

Again—a note.

“Six down. Two to go.”

At this point, Schultz’s own lieutenants began begging him to retreat from Harlem—to absorb the loss, protect the remnant of the organization, and spare the crew from further targeting.

But to retreat meant humiliation.

And for men like Dutch Schultz, humiliation ranks just beneath death.

So he held ground.

And the countdown continued.

VIII. Body Seven — The Crowbar Warning

The seventh killing came with a final warning tone.

The man—a violent extortionist who had terrorized Harlem shopkeepers—was found in the back of a laundromat service alley.

Police arriving at the scene discovered the now-unmistakable folded slip:

“Seven down. One to go.”

Next to the body was a crowbar.

Detectives read symbolism into the objects. They always do.

But Harlem residents did not need symbolism.

They knew what this was:

The last message before the last message.

And somewhere downtown, Dutch Schultz—red-eyed, sleepless, pacing through cigarette smoke—asked the single question he had never imagined asking:

“What if the eighth one is me?”

IX. Schultz’s Final Gambit

Desperation sharpens instinct—and Schultz had one instinct left.

He hired temporary peace-brokers—intermediaries who moved between the white mob world and the Harlem policy underground. Quiet men. Listeners. Fixers.

Their task:

Find Bumpy.

Talk him down.

Stop the eighth killing.

They tried.

The answer returned with icy politeness:

It was too late.

The insult had been public.

The promise had been public.

The consequences would therefore be completed in public view—body by body—until the count reached eight.

There are men you negotiate with.

And there are men who inform you.

Bumpy Johnson informed.

X. Body Eight — The Line No One Crossed Again

The eighth body arrived on schedule.

A Schultz lieutenant left a Midtown garage and never reached his next stop. He was found near the Harlem line just after midnight—no longer a threat to anyone.

The note was shorter than all the others.

“Eight. Stay out.”

No signature.

None was needed.

The week-long blood-message was complete.

And with it, an unwritten law announced itself—so stark that even the newspapers whispered around it:

White racketeers do not run policy in Harlem.

Not anymore.

Not ever again.

XI. The Aftermath — A New Map of Power

The killings stopped as abruptly as they began.

Phones started working again.

Policy houses reopened.

Collectors moved in daylight.

And everyone understood why.

Bumpy Johnson did not replace Schultz’s machinery.

He reconsecrated Harlem’s control over itself.

Within weeks, Schultz’s grip had collapsed.

Within months, his entire empire began to fracture—under legal pressure, under Commission scrutiny, and under the weight of a single fact he could never escape:

He had publicly disrespected a Black man in Harlem—

—and that man had answered.

XII. What History Remembers — and What It Tries to Forget

Official records soften the story.

Police logs list the bodies without the context.

Court transcripts reduce the week to “gangland reprisals.”

But Harlem’s memory is sharper.

People remembered the look on Schultz’s face that night at the Cotton Club.

They remembered the quiet that fell afterward.

They remembered that the killings were not random—

—they were numbered.

And they remembered the lesson:

Some neighborhoods are not colonies.

Some people are not property.

And certain insults carry costs that compound quickly.

XIII. The Meaning Beneath the Myth

It is tempting to romanticize this story—to turn it into legend or cautionary fable. But the truth is heavier.

Eight men died violent deaths.

Families grieved.

Harlem remained poor.

Racism did not end.

And yet—

—something real shifted.

A white mob boss walked into Harlem believing that law, race, and money made him untouchable.

He left Harlem humbled by the one resource he never understood:

dignity enforced.

Johnson did not wield power theatrically.

He wielded it with cold arithmetic.

And in doing so, he redrew the map.

Not with ink.

With memory.

Epilogue — The Echo in the Horns

On some later night, the Cotton Club band played a slow number. The lights glowed low and gold. The audience laughed again. Drinks clinked. Life resumed.

But beneath the brass and bass, the street still remembered the week Harlem spoke in numbers.

Eight.

And never again.

News

While In Coma, My Husband and Lover Planned My Burial, Until The Nurse Said ‘She’s Back’ Then | HO

While In Coma, My Husband and Lover Planned My Burial, Until The Nurse Said ‘She’s Back’ Then | HO When…

3 Weeks After Their Wedding, He Sh0t his Wife 15 times for Getting Him the Wrong Christmas Gift | HO

3 Weeks After Their Wedding, He Sh0t his Wife 15 times for Getting Him the Wrong Christmas Gift | HO…

Hiker Vanished in Colorado — 5 Years Later, She Staggered Into a Hospital With a Shocking Truth | HO

Hiker Vanished in Colorado — 5 Years Later, She Staggered Into a Hospital With a Shocking Truth | HO On…

The Bank Called: ‘Your Husband Is Here With A Woman Who Looks Just Like You…’ | HO

The Bank Called: ‘Your Husband Is Here With A Woman Who Looks Just Like You…’ | HO At 2:47 p.m….

Teen K!ller LOSES It In Court After Learning She’s Never Going Home | HO

Teen K!ller LOSES It In Court After Learning She’s Never Going Home | HO In the final moments before the…

Mother Caught Cheating With Groom At Daughter’s Wedding – Ends In Bloody Murder | HO

Mother Caught Cheating With Groom At Daughter’s Wedding – Ends In Bloody Murder | HO On a warm evening in…

End of content

No more pages to load