$950K Stolen From Harlem Jewelry Store in 1990 — 30 Years Later, Chain Surfaces at Police Auction | HO!!!!

When the Harlem sun rose on October 12, 1990, one of the city’s most respected jewelers was already staring into ruin. Harold Banks & Sons — a community landmark on 125th Street — had been stripped clean overnight. Nearly a million dollars’ worth of diamonds, gold, and platinum vanished in what detectives would later call “the most surgically executed jewelry heist in New York City history.”

For decades the case lay dormant, locked in the archives of the NYPD’s robbery division, a cold file with no suspects and no hope. Until, in 2020, a small clerical auction of unclaimed evidence unearthed one overlooked piece: a gold Cuban-link chain engraved HB 6-12-84.

That single detail would reopen a mystery the city had long forgotten — and expose the quiet betrayal that made it possible.

A Store Built on Trust

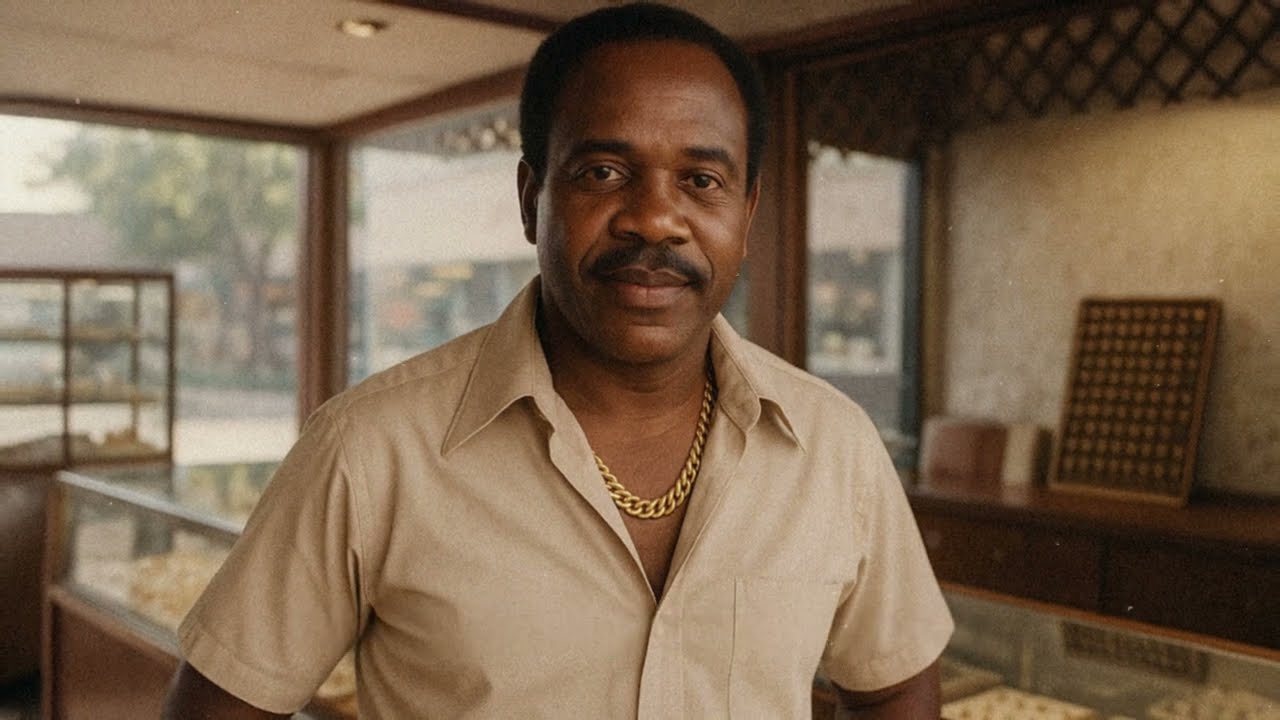

In the late 1980s, Harold Banks was more than a jeweler. He was Harlem royalty. His storefront glittered not just with gold but with pride — one of the few Black-owned luxury businesses to thrive in an era defined by upheaval.

Every evening, his staff locked the day’s most valuable pieces into three sealed crates marked for overnight pickup by a private security service. A night guard, Lawrence Given, was responsible for handing those packages to the armored-car team before midnight.

On October 11, 1990, that routine became the script for one of New York’s cleanest crimes.

The Perfect Fifteen Minutes

At 10:50 p.m., motion detectors in the rear hall of Banks & Sons tripped. Eight minutes later the first patrol car arrived. Inside, chaos — but no thieves. Two glass cases shattered, three shipping crates empty, and Given bound with duct tape in a supply closet.

He told police he’d opened the service door for men he believed were couriers. They struck him, tied him up, and disappeared. The story held. His injury was minor but convincing. No fingerprints. No forced entry. The alarm system, conveniently, had been “under repair.”

Within days, investigators admitted they had nothing. The loss totaled $950,000. Banks’s own custom chain — a heavy gold Cuban link he’d commissioned in 1984 — was also missing, though it never appeared on the official inventory. The owner’s inconsistent statements about when he last wore it led detectives to dismiss it as unrelated.

By 1992, the file was closed.

The Chain That Waited

For thirty years, the robbery became legend — a training-manual case study in precision crime. Then came the auction.

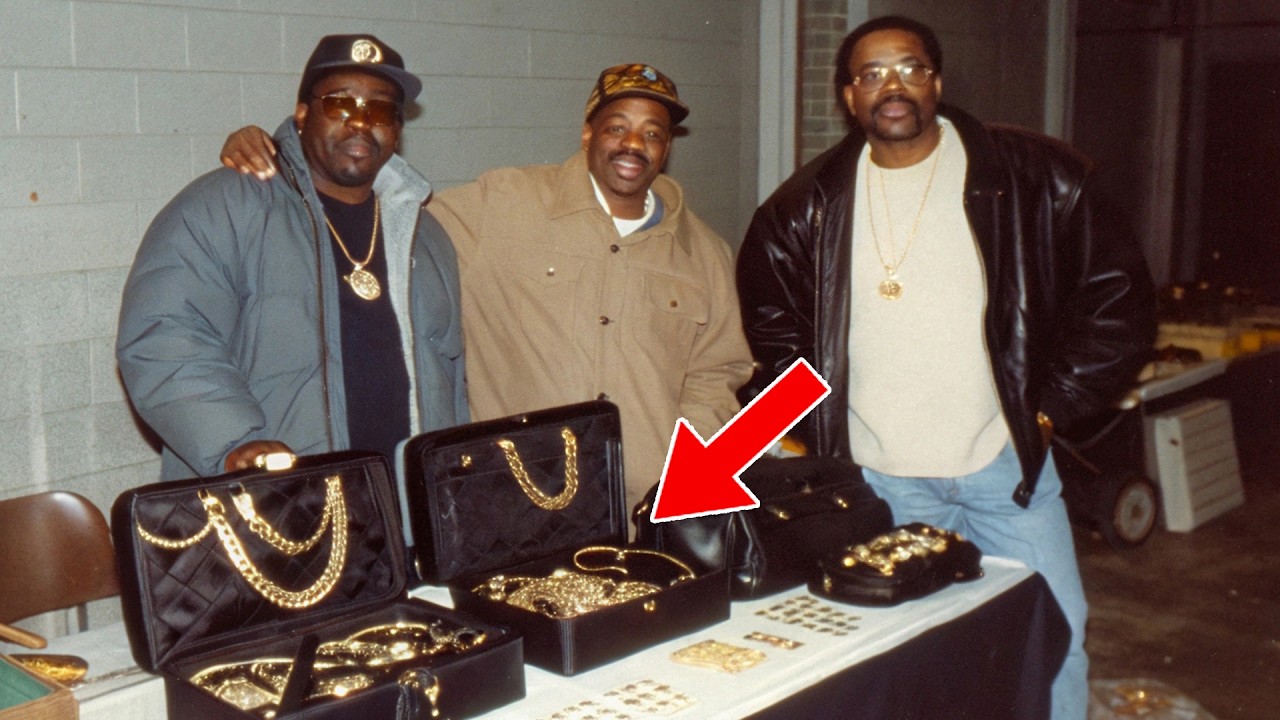

In early 2020, as part of a routine purge of unclaimed evidence, the NYPD listed hundreds of items online: tools, electronics, and unmarked jewelry. Lot #4823 was described simply as “vintage gold chain, unknown origin.”

A Bronx jeweler named DeAndre Lewis, known for restoring handcrafted pieces, bought it for under $400. The weight felt wrong for costume work — too dense, too deliberate. Under a loupe, he saw the faint engraving: HB 6-12-84.

He remembered an old trade-magazine feature on Harold Banks, complete with a photograph of the jeweler wearing an identical chain. The date matched the store’s sixth anniversary. Lewis called the NYPD.

From Evidence Locker to Cold Case

Detectives traced the chain’s tag number to a forgotten file. It had been seized in June 2002 during a routine narcotics arrest in Manhattan. The suspect, James Webster, used an alias and served a short sentence. The necklace, lacking identifying marks, was boxed and shelved. For eighteen years it sat unnoticed in a Queens evidence room.

Now, with the engraving confirmed and the provenance clear, the cold-case unit reopened the 1990 file. Cross-checking records revealed a coincidence too large to ignore: Webster was cousin to Lawrence Given, the night guard who had “survived” the heist.

The Confession

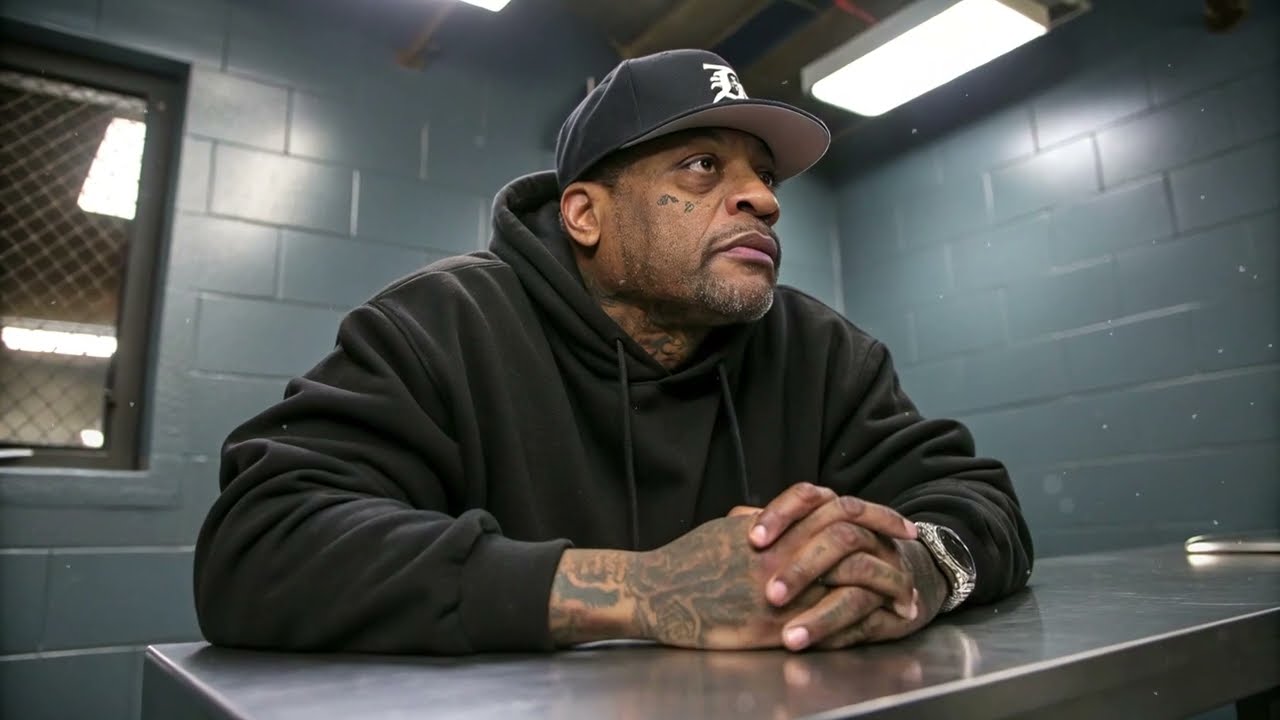

Detectives located Webster in Brooklyn, living under a new variation of his name. Facing minor probation violations, he agreed to talk.

What he described was not a chaotic smash-and-grab, but an inside job planned with military precision.

According to Webster, the idea came from Given himself. After a year on the night shift, Given knew every blind spot, every schedule, every keypad code. He proposed staging a fake courier delivery minutes before the real security van was due.

Webster recruited a third man — Rodney Dyson, a Bronx associate. The trio rehearsed the timing for weeks. Their guiding rule: no fingerprints, no panic, no bodies.

On the night of October 11, Given opened the side door at 10:40 p.m. Dyson struck him lightly with a flashlight, drawing blood for realism. They bound him, locked him in the closet, and used his keycard to reach the holding room. In under ten minutes they forced open the three shipping crates and filled duffel bags with pre-packed inventory.

But greed ruined perfection. Dyson detoured into the showroom, smashing two display cases. The vibration triggered a secondary alarm unknown to Given. The men bolted, escaping into an alley as patrol cars closed in.

Given played his part flawlessly — dazed, bleeding, cooperative. Police never suspected him.

That night, in a rented garage in Queens, the three men divided the loot. They swore never to meet again.

The Vanishing Act

Over the next decade, the thieves dissolved into the city’s background noise.

Given kept his job for 18 months, then quietly resigned and moved to New Jersey.

Webster melted down his share, selling the gold through street dealers.

Dyson disappeared entirely, later resurfacing under a new name in Maryland.

Only one piece remained untouched: Harold Banks’s personal chain, stolen privately by Given from the office safe and never mentioned to the others. Years later, when Given owed Webster money, he paid the debt with that chain.

When police raided Webster’s apartment in 2002 on a drug warrant, the necklace was seized but misfiled — its engraving unnoticed, its story erased.

The Investigation Reborn

Three decades later, the rediscovery of that engraving reignited the cold case. Detectives confronted Webster with photos of the chain and the 1991 magazine article. Under pressure, he confessed in detail, describing the plan, the timing, and every player involved.

The legal outcome, however, was anticlimactic. New York’s statute of limitations for robbery had long expired. Dyson was dead — killed in 2011 during a narcotics shootout. Given, living quietly in New Jersey, admitted his role but could no longer be charged.

No one went to prison. But the truth, finally, was on record.

Closure Without Justice

In a private ceremony, the NYPD returned the recovered chain to Harold Banks, now retired and living upstate. Tarnished but intact, the piece had survived thirty years, two evidence systems, and three generations of detectives.

The old jeweler held it for a long moment before speaking. “They said I lost it before the robbery,” he murmured. “Guess they were wrong.”

His former storefront is now a smoothie bar. The gleaming counters where diamonds once sparkled serve acai bowls to strangers who know nothing of the night Harlem lost its gold.

The Lesson in the Chain

Within the department, the case became a cautionary parable. A single mis-tagged item — a clerical slip — had hidden the answer in plain sight for nearly two decades.

“Evidence doesn’t age,” one cold-case detective wrote in the final summary. “Only our systems do.”

The file now rests in the NYPD archives labeled Solved — Non-Prosecutable. No handcuffs, no verdict, just a record of what truly happened: three men, fifteen minutes, and a city fooled for thirty years.

Yet the gold chain tells the story better than any report.

It is the shimmer of greed, the glint of loyalty betrayed, and the final proof that even the smallest detail — a pair of engraved letters and a forgotten date — can drag the past, kicking and gleaming, back into the light.

News

She Disappeared From a Locked Room in 1987 — 17 Years Later, One Object Rewrote the Entire Story | HO!!

She Disappeared From a Locked Room in 1987 — 17 Years Later, One Object Rewrote the Entire Story | HO!!…

He Checked the Baby Camera — And What He Saw Ended His Marriage | HO

He Checked the Baby Camera — And What He Saw Ended His Marriage | HO PART 1 — A Quiet…

Husband Burns House Down To Hide Evidence Of K!lling His Wife… After Dumping Her In Pickup Truck | HO

Husband Burns House Down To Hide Evidence Of K!lling His Wife… After Dumping Her In Pickup Truck | HO PART…

American Fiancée Murders Saudi Sheikh After Discovering His 12 Secret Children Worldwide | HO

American Fiancée Murders Saudi Sheikh After Discovering His 12 Secret Children Worldwide | HO PART 1 — The Call, the…

Dubai Sheikh Pays $3M Dowry for Filipina Virgin Bride – Wedding Night Discovery Ends in Bl00dbath | HO

Dubai Sheikh Pays $3M Dowry for Filipina Virgin Bride – Wedding Night Discovery Ends in Bl00dbath | HO PART 1…

Rapper Orders Hit On His FATHER From Jail For Impregnating His SON’S WIFE | HO

Rapper Orders Hit On His FATHER From Jail For Impregnating His SON’S WIFE | HO It is a murder plot…

End of content

No more pages to load