A Happy Family in 1906 — But the Youngest Son Hides Something Shocking | HO!!

When Dr. Sarah Chen, curator at the National Museum of Medical History, first examined the glass plate negative sent from a Philadelphia estate, she expected another routine addition to the museum’s archives.

Instead, she uncovered a haunting story that has remained silent for over a century—a story of love, loss, and the hidden epidemic that shaped early 20th-century America.

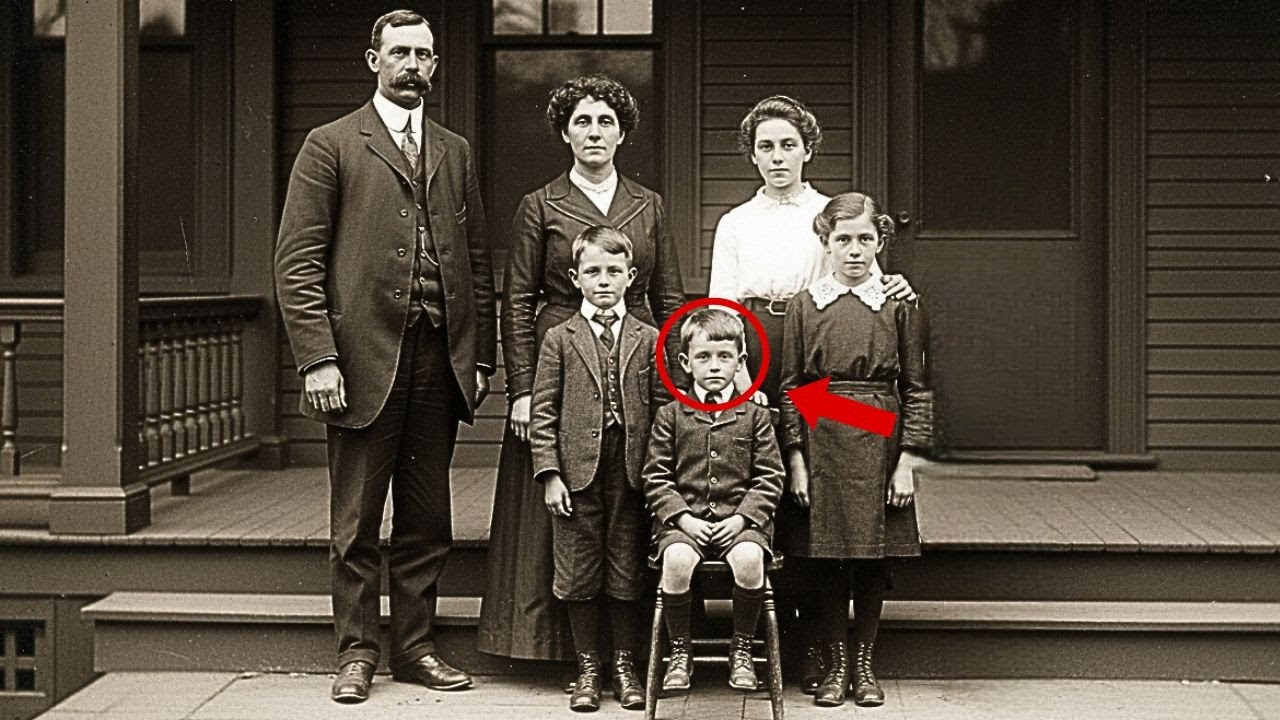

The photograph, dated summer 1906, depicted the Bennett family: six members posed on the porch of a tidy wooden house, the image of middle-class prosperity. Dr. Howard Bennett, a respected city physician, stood on the left, his wife Catherine beside him, her hand protectively resting on their eldest daughter’s shoulder.

Three children stood in order—Elizabeth, Robert, and Caroline. At the front, seated on a small stool, was the youngest, Joseph Bennett, age six. Everyone smiled for the camera, radiating health and security. But beneath the surface, the photograph concealed a devastating truth.

A Curator’s Discovery

Sarah Chen specializes in the history of infectious diseases. She has spent years studying historical medical photographs, learning to recognize subtle signs of illness that often escaped the notice of their subjects. As she examined the Bennett family portrait, her trained eye was drawn to Joseph.

His cheeks were hollow, his eyes unusually bright, and his posture fragile. Using a magnifying loop, Sarah noticed a detail that made her heart race: Joseph’s fingertips were clubbed—a telltale sign of chronic low oxygen, most commonly caused by tuberculosis in children of that era.

Sarah dug deeper into the documentation accompanying the donation. The estate belonged to Dr. Howard Bennett, who had practiced in Philadelphia from 1895 until his death in 1952. Among his professional materials were personal effects and family photographs, including the 1906 portrait. Donation records indicated that Dr. Bennett had four children, but only three survived to adulthood. The youngest, Joseph, was born in 1900.

Uncovering the Family Secret

Sarah found further evidence in Bennett’s medical journals from 1906 and 1907, which included articles about childhood tuberculosis. One margin, in Bennett’s handwriting, simply read “Joseph.” The clues pointed to a tragic diagnosis.

Seeking confirmation, Sarah contacted Ellen Porter, Dr. Bennett’s great-granddaughter and the donor of the collection. Ellen’s response was hesitant but honest. “My grandmother, the oldest girl in that photograph, told me about Joseph before she died,” Ellen said. “She made me promise never to discuss it publicly. She said it was too painful.”

Sarah explained the importance of Joseph’s story to medical history. If Dr. Bennett, a physician specializing in chest diseases, had treated his own son for tuberculosis, it could shed light on how families—and doctors themselves—confronted the epidemic. Ellen finally revealed the truth: Joseph had contracted tuberculosis in the spring of 1906. Despite his father’s expertise, the disease progressed rapidly. “Tuberculosis was shameful then,” Ellen said. “People treated it like a moral failing, like it only happened to the poor. For a doctor’s family to admit one of their children had it—they kept it secret.”

Joseph died in January 1907, seven months after the photograph was taken. Ellen explained that the portrait was created intentionally while Joseph was still strong enough to sit up and smile—a memorial in advance, before the family was irreparably changed.

A Father’s Despair

Sarah’s research into Dr. Bennett’s personal papers revealed a man caught between professional expertise and utter helplessness. Bennett’s journal entries from 1906 began clinically, but soon became desperate.

“April 12th, 1906. Joseph has begun coughing at night. I tell myself it is merely a spring cold, but I cannot ignore what my training tells me. I examined his chest this morning. The sounds are unmistakable. Dear God, not this, not my son.”

Bennett documented every symptom, every failed remedy. He consulted colleagues, considered sending Joseph to a sanitarium for fresh mountain air—a common but often futile treatment. But he refused to let his son die among strangers. The family converted their sleeping porch into a recovery room, isolating Joseph from his siblings to protect them.

Katherine Bennett’s letters to her sister in Boston, found among the family papers, described the heartbreak of watching Joseph grow weaker, the children tiptoeing through the house “like ghosts,” and her husband’s nightly vigils at Joseph’s bedside.

The Stigma of Disease

In early 20th-century America, tuberculosis was more than a medical crisis—it was a social catastrophe. Families faced ostracism, loss of employment, denial of insurance, and exclusion from schools. Dr. Bennett’s own notes reveal the fear: “Families of TB patients face social ostracism. Children denied school admission. Fathers lose employment.”

Philadelphia, in 1906, had one of the highest tuberculosis death rates in the country. The germ theory of disease was still new, and many believed tuberculosis was hereditary or a sign of moral weakness. Public health campaigns were hampered by stigma, forcing families like the Bennetts to hide their suffering.

Sarah found evidence that this secrecy was widespread. In New York, health workers conducting tuberculosis surveys faced resistance from families terrified of quarantine and eviction. Most sick children went undiagnosed and untreated. The Bennett family’s experience, it turned out, was tragically common.

Turning Grief Into Change

Despite the pain, Dr. Bennett refused to let Joseph’s death be meaningless. Sarah discovered correspondence between Bennett and Dr. Edward Trudeau, a pioneering tuberculosis researcher. Bennett sent Trudeau detailed medical notes and samples from Joseph’s case, hoping to contribute to scientific understanding. Trudeau’s response was encouraging: Joseph’s case provided crucial data on childhood tuberculosis progression, influencing diagnostic criteria and treatment recommendations.

After Joseph’s death, Bennett became a tireless advocate for tuberculosis research and public health reform. He published over 30 papers, served on committees, and testified before government bodies.

In a 1910 address to the Pennsylvania State Legislature, Bennett spoke as both physician and grieving father: “Tuberculosis is not moral failing. It is bacterial infection that can strike any family regardless of wealth or social standing. If we continue to stigmatize tuberculosis, families will continue to hide sick children until it is too late.”

His advocacy was ahead of its time. Pennsylvania would not establish a comprehensive tuberculosis program until 15 years later.

A Photograph’s Lasting Legacy

Sarah Chen spent six months curating an exhibit titled “The Hidden Epidemic: Childhood Tuberculosis in America, 1900–1950.” The Bennett family photograph became its centerpiece. Enlarged and displayed with magnified details of Joseph’s face, the image forced visitors to confront the reality behind the smiles—a child dying of a disease his father was powerless to cure.

The exhibit included other family portraits, letters, and medical records, illustrating the human cost of the epidemic and the silence imposed by stigma. Visitors lingered before the Bennett photograph, reading the story and seeing, perhaps for the first time, the hidden suffering of families like theirs.

Ellen Porter attended the opening with her daughter and grandson—three generations honoring Joseph’s memory. “He looks happy,” Ellen’s grandson said, quietly. “Even though he was sick.” Ellen replied, “He was loved. That’s what this photograph really shows. A family that loved him enough to document his life, even knowing how it would end.”

Breaking the Silence

The exhibit drew praise from medical schools, public health organizations, and historians. It humanized statistics, sparking conversations about disease stigma and the importance of public health infrastructure.

Sarah’s lecture at the opening summarized Joseph’s legacy: “Joseph Bennett died in 1907, but his story didn’t end there. His father made sure of that. Dr. Bennett spent 45 years fighting to change how society treated tuberculosis, to remove the stigma, to improve public health responses. He couldn’t save his own son, but his work helped save countless other children.”

After the lecture, Ellen thanked Sarah for giving Joseph a voice. “My grandmother spent her whole life keeping his story secret because she was ashamed. But there was never anything to be ashamed of. Joseph was just a little boy who got sick. He deserved to be remembered.”

As Sarah looked once more at the photograph, she saw more than a sick child—she saw a bridge between past and present, a family’s love, and a lesson for generations. Joseph Bennett’s smile, preserved for over a century, had finally broken the silence.

News

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO”

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO” It…

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He Kil.. | HO”

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He…

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You | HO”

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You |…

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO”

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO” Her…

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO”

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO” A…

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

End of content

No more pages to load