A Janitor Found a Taped-Up Door in a School Basement — It Led to a Classroom Missing Since 1978 | HO

The Classroom That Durham Tried to Forget

In the autumn of 2025, long after the city’s factories had gone silent and its downtown was gentrified into a postcard of polished brick and brunch cafés, a janitor named Arthur Coleman made a discovery that would reopen one of Durham’s darkest secrets.

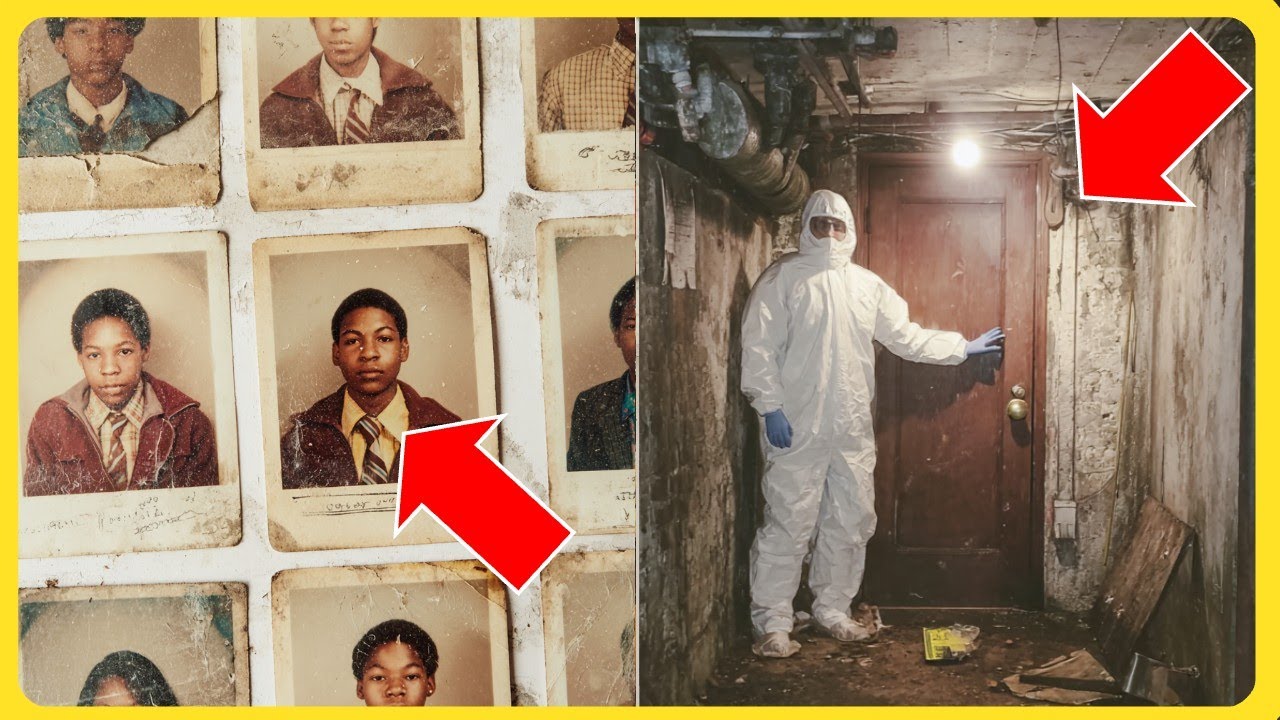

He’d been working at Vance Intermediate School for nearly thirty years—a man invisible by design, who swept the same linoleum halls every evening while teachers hurried home. That day, the renovation crew had torn down an old partition on the north wing, revealing something no blueprint said should exist: a door, sealed shut with concrete and steel brackets.

Arthur wasn’t a man given to curiosity. He’d seen enough ghosts of the past hiding behind drywall. But something about this door felt wrong—not just forgotten, but erased. The bolts were rusted, and the wood was stamped with an official seal: “Property of the State of North Carolina. Closed – 1978.”

He stared for a long time before prying it open with a crowbar. The smell hit first—stale paper, dust, and the faint metallic tang of something that hadn’t breathed in nearly fifty years.

Inside was a classroom. Perfectly preserved.

Desks sat in neat rows, a chalkboard still covered in half-erased equations, and a faded portrait of Jimmy Carter hung crooked above the teacher’s desk. Time had stopped here, right around the spring of 1978—the year Mr. Harold Vance, the school’s only Black history teacher, vanished along with twelve of his students.

The city had whispered about that story for decades. Some said it was an accident, others a cover-up. But no one ever found the classroom. Officially, it had “never existed.”

The Year of Disappearance

In 1978, Durham was a city at war with its own reflection.

White developers, backed by the county’s political machine, were carving highways straight through Black neighborhoods—Hayti, East End, Lyon Park—erasing generations of homeownership in the name of “progress.” When Mr. Vance began teaching his students about those land deeds, tracing the signatures that had stolen their grandparents’ homes, he was warned to stop.

He didn’t.

One March morning, his class didn’t show up for lunch. The principal called it a “field trip that went astray.” Within days, the police declared the case a “transportation accident.” No bodies were found. Parents were told to “move on.” Then, mysteriously, the classroom was sealed.

Within a month, the entire school district was redrawn, and new property deeds transferred ownership of several parcels—including the land under Vance Intermediate—to a real estate firm tied to a local senator.

Durham buried the story. Literally.

Arthur’s Discovery

Standing in the dark decades later, Arthur ran his hand across the teacher’s desk. There were notebooks still stacked neatly, pages yellowed but legible.

On the first one, in neat cursive:

“If they erase us, who will teach them what they stole?”

He turned the page. Inside were maps—hand-drawn records of Durham’s Black neighborhoods, each marked with notes about property transfers, zoning changes, and unexplained fires. It wasn’t just a classroom; it was a war room.

At the back of the room, behind a curtain of cobwebs, Arthur’s flashlight found a second wall—one that shouldn’t have been there. It looked newer than the rest, smooth and cold. Someone had built it to hide something.

He pressed his palm against it and felt a hollow echo. Using a maintenance hammer, he struck twice. On the third hit, plaster cracked and fell away.

Beneath it was a mural.

The Wall That Remembered

It stretched across the entire length of the room—painted in deep, dark pigments that had somehow survived the decades.

At first, it seemed like chaos: handprints, scribbled names, streaks of red and white chalk. But as Arthur’s eyes adjusted, the pattern emerged.

There were thirteen handprints—twelve small, one large—arranged in a circle. Around them, the names of Durham’s displaced neighborhoods were written like prayers: “Hayti,” “Pettigrew,” “Fayetteville Street,” “Old West End.”

And in the center, written in thick, uneven chalk, were the words:

“They can bury us, but the land remembers.”

Arthur staggered back. The air grew colder. The flashlight flickered.

On the desk behind him, one of the notebooks fell open by itself—to a final page filled entirely with a message in white chalk dust:

“Tell them we were learning.”

The Lost Twelve

In the weeks that followed, the discovery made local headlines.

City officials called it “a historic artifact.” The school board promised to “review the findings.” But within days, the room was resealed under “hazardous conditions.” Reporters were turned away.

Arthur tried to speak at a council meeting and was cut off mid-sentence. The next morning, his employment was “terminated due to restructuring.”

But word spread anyway.

Former residents of Durham’s Black neighborhoods began coming forward with memories—grandparents who’d attended Vance’s classes, family photos with children who “never came home,” whispers of a school project meant to expose city corruption.

And then there was the tape.

A retired TV cameraman, cleaning out his attic, found a film reel labeled “Durham County – Education Board Meeting – 1978.” The footage, though degraded, showed a brief, frantic scene: Harold Vance standing before city officials, holding up a map identical to the one Arthur found. His voice was faint, but his words clear enough:

“You can burn the deeds. You can rename the streets. But the ground itself will remember who it belonged to.”

Moments later, the reel cut to static.

What Remains

Arthur’s discovery never reached the national news. Within months, the sealed classroom was demolished during “campus modernization.”

When crews broke ground for a new athletic complex, they found unmarked bones beneath the foundation—small ones, belonging to children. The police called it “historical material,” unconnected to any ongoing case.

Arthur left Durham soon after. No one knows where he went. Some say he mailed copies of the notebooks to civil rights lawyers in Raleigh. Others believe he’s still somewhere in North Carolina, chasing the truth through the state archives.

The official record lists Harold Vance and twelve students as “presumed deceased.” No mention is made of their classroom, their research, or the mural that defied time.

But among the city’s older residents—those who still remember the smell of chalk dust and the sound of hymns echoing from wooden classrooms—there’s a story that refuses to fade.

They say that on humid summer nights, when the new gymnasium lights shut off and the crickets fall silent, you can still hear faint voices from beneath the concrete:

children reciting lessons, a teacher writing on the board.

And if you stand close enough, you might see it too—the words that survived every bulldozer, every lie, every silence carved into the city’s bones:

“Tell them we were learning.”

News

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO “How,” he…

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO On February 3, 2020, Richmond Police…

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… | HO

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… |…

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know | HO

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know…

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫…

End of content

No more pages to load