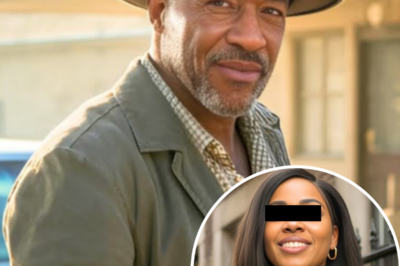

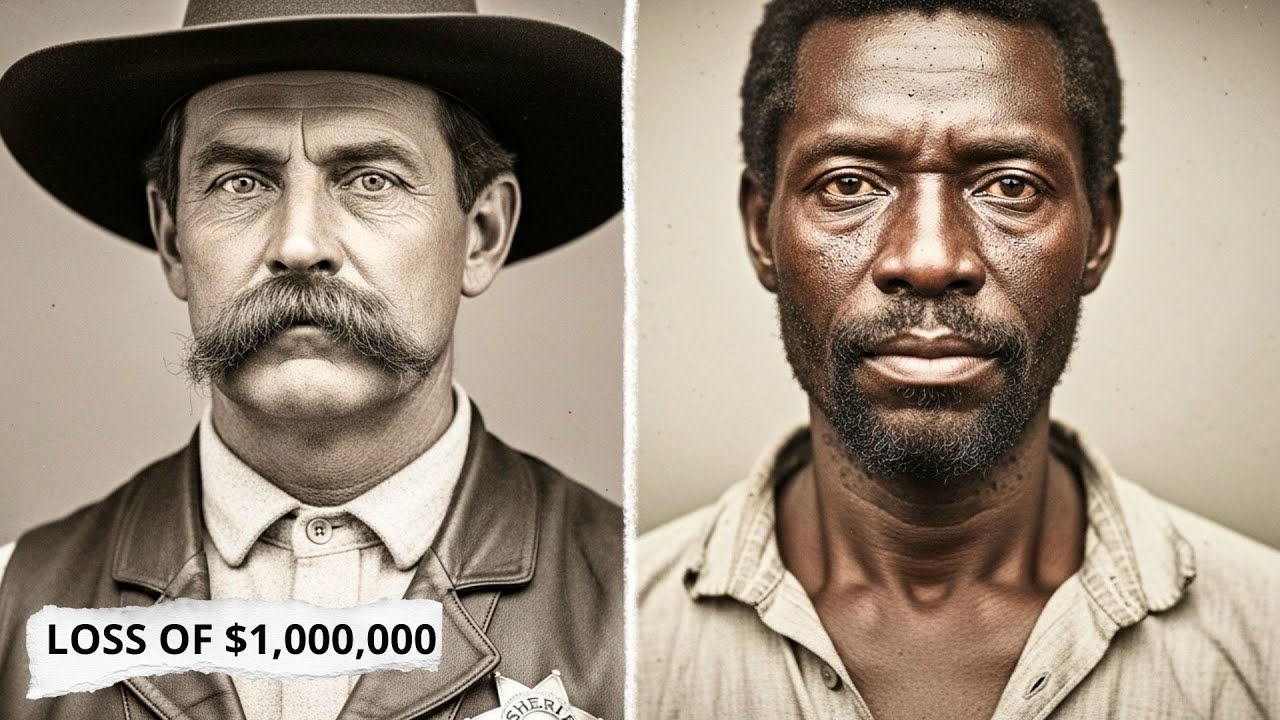

A sheriff and a slave caused $1,000,000 in losses to plantation owners in Virginia in 1849 | HO!!

I. The County That Prospered on Chains

In the spring of 1849, something unprecedented began to unfold in Albemarle County, Virginia—a rebellion so quiet, so methodical, that no one recognized it as a revolution until it was too late.

A white sheriff named Thomas Garrett and a runaway slave named Daniel waged a campaign that would devastate twenty-three plantations and cost Virginia’s ruling class more than a million dollars. They didn’t set fires. They didn’t steal money. What they took was infinitely more valuable: human beings.

For six months, Garrett and Daniel freed 347 enslaved men, women, and children, unraveling the economic foundation of a county built on bondage.

The story of how a lawman sworn to uphold slavery became its fiercest enemy is darker and more shocking than any legend carved into courthouse marble. It’s a story buried in courthouse records, whispered in Quaker journals, and etched into the oral histories of Black families across generations—a story of conscience, betrayal, and the terrible price of doing what’s right.

II. The World Thomas Garrett Inherited

In 1849, Albemarle County was a portrait of the Old South’s contradictions.

The James River glittered in the sunlight, flowing past grand estates with names like Oakmont, Greenfield, and Rose Hill—white-columned mansions that proclaimed wealth built on the backs of 8,000 enslaved people. Nearly 40% of the county’s population lived and died in chains.

The plantation economy was an intricate engine of cruelty. Men, women, and children toiled from sunrise to nightfall. Public whippings and “slave patrols” enforced control. Virginia’s laws forbade literacy, property, assembly, and testimony. An enslaved person who ran once was whipped. Twice, branded. Three times, executed.

The system was designed to make slavery eternal.

Into this world was born Thomas Garrett, the son of a poor white farmer who owned no slaves and no illusions about the gulf separating him from the wealthy planters who dominated the county. Thomas’s family worked their own small tobacco farm outside Charlottesville. They were free but powerless, respectable but poor—reminded daily that “white” didn’t necessarily mean “wealthy.”

His mother, Elizabeth Garrett, a former schoolteacher, insisted her sons be educated. Thomas proved gifted, mastering reading, writing, and arithmetic before most boys his age could sign their names.

That education changed his life. At eighteen, he left the farm to clerk at the county courthouse, where he learned the machinery of law—the same law that treated human beings as livestock.

By twenty-six, Garrett was a deputy sheriff. By thirty-two, he was elected sheriff of Albemarle County. His job was to keep the peace. But in a society where peace was built on chains, that meant enforcing the unthinkable.

III. The Whipping That Broke a Lawman

The moment that changed everything came in 1842.

Garrett was ordered to help recapture a runaway slave named Rebecca, property of Colonel Richard Ashford—one of the wealthiest men in the county.

Rebecca was seventeen. Light-skinned. Pregnant. She’d been raped repeatedly by Ashford’s son, Marcus, a violent young man whose cruelty was whispered about even among other planters. When Rebecca realized she was pregnant, she fled—knowing that exposure meant she would be sold “downriver” to Louisiana, where death came faster than harvest.

She made it fifteen miles before the dogs caught her.

Garrett watched as she was dragged back in chains, stripped to the waist, and whipped fifty times in Charlottesville’s public square—her swollen belly visible to the crowd. Her screams tore through him.

He’d seen punishment before. But this was different. This was a human being, a child, tortured for trying to survive.

When it was over, Rebecca was sold to a trader from New Orleans for $800. She vanished into the hellish pipeline of the Deep South. Garrett never saw her again. But he never forgot the sound of her voice.

That night, he couldn’t sleep. For the first time in his life, the idea that slavery was “necessary” began to crack.

IV. The Quiet Radicalization of a Sheriff

The doubt spread slowly, like rot beneath a polished floor.

Garrett began reading contraband abolitionist literature—pamphlets smuggled from the North, Frederick Douglass’s autobiography, William Lloyd Garrison’s fiery sermons, Quaker treatises declaring slavery a sin before God.

He attended secret Quaker meetings, invited by a farmer named Isaiah Miller. There, by candlelight, people whispered prayers for the enslaved. They offered shelter to runaways. They spoke of freedom as a sacred duty.

Garrett listened, torn between his oath and his conscience. As sheriff, he enforced the Fugitive Slave Law. As a man, he began to hate it.

For years, he did nothing. He told himself he was gathering information, waiting for the right time to act. In truth, he was afraid.

Then came January 1849, and a stolen sack of food that changed everything.

V. The Man in the Woods

A plantation owner named William Preston reported that his smokehouse had been robbed—ham, cornmeal, bacon. A petty crime, but in Virginia, theft by a slave was punishable by mutilation or death.

Garrett investigated out of duty. He questioned the enslaved workers, found nothing. That night, riding home, he spotted movement in the trees—a man, tall and lean, carrying a sack.

The man didn’t run. He simply waited.

When Garrett approached, he saw scars on his wrists—shackle burns. The man’s voice was calm. “I took the food,” he said. “Been four days since I ate.”

His name was Daniel. He’d escaped from a plantation in North Carolina and was making his way north.

Garrett was supposed to arrest him. Instead, he lowered his weapon.

“You know what’ll happen if I take you back?” Garrett asked.

“I do,” Daniel said. “You going to do it?”

Garrett hesitated. “No. Not tonight.”

That conversation, whispered in the cold Virginia woods, was the birth of a rebellion.

VI. The Underground Within the Law

Over the next hours, they talked—two men from opposite sides of America’s moral divide.

Daniel told him about his family, sold off piece by piece. About learning to read in secret. About the years spent planning his escape. Garrett confessed his disgust for the system he served, his guilt over Rebecca, his hatred for the laws he upheld.

Together, they made a pact.

Daniel would stay in Albemarle County, building a hidden camp in the forest as a waystation for escapees. Garrett would use his badge as a shield—investigating reports of “runaways,” but never catching them. He’d feed Daniel information: patrol schedules, bounty hunters’ routes, safe passage north.

Within weeks, the first fugitives arrived. A man named Isaac reached Daniel’s camp half-dead. Garrett staged a search, returned empty-handed, and later drove Isaac north under the guise of official business.

By February, five people were free. By March, twelve more. By April, dozens.

Word spread quietly through the enslaved community—through coded songs, quilt patterns, whispers in the fields. The message was clear: “If you make it to Albemarle, the sheriff won’t catch you.”

VII. The Family and the False Arrest

By March, a family of five—Samuel, Martha, and their children—sought refuge. Traveling with children was suicide; the youngest was four, too small to walk far. But Thomas Garrett devised a plan so audacious it almost defied belief.

He claimed to have captured a family of fugitives and needed to transport them to Richmond for trial. The wagon was covered. The “prisoners” were chained for show. Two deputies rode along as escorts.

But instead of heading east to Richmond, Garrett turned north. Three days later, the family crossed into Pennsylvania—free soil.

He returned to Virginia, his wagon empty, claiming “abolitionists” had attacked and freed the prisoners. No one doubted him.

That spring, escapes became an epidemic. By May, over 150 people had vanished from Albemarle’s plantations. The economy began to fracture. Crops withered in the fields. Owners fumed.

They didn’t know that the enemy was their own sheriff.

VIII. The Price of Freedom

By June 1849, Garrett and Daniel’s network had freed 213 people.

Plantation owners hired professional slave-catchers from Richmond. They demanded investigations. Garrett responded with feigned diligence—sometimes capturing minor runaways to protect the operation.

But the pressure mounted. He knew it couldn’t last.

The end came not from betrayal, but from desperation.

A woman named Sarah, enslaved at Ashford Plantation—the same estate where Rebecca had been whipped years earlier—appeared at Garrett’s jail one summer morning. She turned herself in.

“I know who you are,” she told him calmly. “I know about Daniel. I know what you’ve done.”

Garrett’s blood ran cold.

“Then why are you here?” he asked.

“Because my daughter, Ruth, is about to be sold south. She’s fifteen. Marcus Ashford’s been raping her. She’s pregnant. I need your help to get her out—or I’ll tell them everything.”

It was blackmail. But it was also a mother’s plea.

Garrett agreed.

IX. The Raid on Oakmont

They had one week.

Daniel gathered six men—escaped slaves now living in Pennsylvania—who returned south to risk everything for a girl they had never met.

On July 14th, 1849, Garrett arrived at Oakmont with deputies, pretending to investigate a “horse-thief ring.” While Ashford entertained him inside, Daniel’s team slipped onto the grounds, found Ruth in the slave quarters, and led her toward the woods.

They almost made it.

An overseer spotted them. Bells rang. Guns cocked. Garrett burst outside and saw Daniel surrounded, Ruth cowering behind him.

Then he did the unthinkable. He stepped between the armed guards and the fugitives.

“Lower your weapons,” he ordered. “These men are under arrest. They’re part of the escape network. I’ll take them myself.”

The ruse worked. He loaded Ruth and the others into his wagon and rode away.

Miles later, he stopped in the woods, unlocked their chains, and said, “Run.”

Ruth reached her mother that night. They disappeared north with Daniel. Garrett turned back toward Charlottesville, rehearsing his lie.

He didn’t know it yet, but his time was over.

X. The Trial of the Sheriff

Two days later, he was arrested.

Plantation owners had pieced it together. Sarah had been caught on her way north, tortured until she confessed. The conspiracy unraveled.

Garrett was charged with aiding fugitives, conspiracy, theft, and treason against Virginia. He was locked in his own jail—the same cells where he’d once held others.

His trial, held in August 1849, was a spectacle. The courtroom overflowed with angry planters demanding vengeance.

The evidence was overwhelming. The jury—all slave owners—needed less than an hour to convict.

Before sentencing, the judge asked if he had anything to say. Garrett stood for three hours.

He didn’t beg for mercy. He exposed the system. He described Rebecca’s rape and whipping in excruciating detail. He told the stories of the men and women he’d helped—naming them, humanizing them, forcing his accusers to see what they’d denied.

Then he turned on them.

“You will punish me,” he said, “but I am not the criminal. You are. You built a nation on stolen bodies. You call me traitor? History will call you monsters.”

The courtroom exploded. He was sentenced to twenty years hard labor at the Richmond penitentiary.

XI. The Legacy of Rebellion

In prison, Garrett broke rocks and forged iron chains—the cruelest irony imaginable.

Daniel made it to Canada with Sarah and Ruth. They settled near Toronto, part of a community of escaped slaves. When the Civil War began, Daniel returned to fight with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first Black regiment to see major combat. He survived the war and lived to see slavery abolished.

His tombstone in Ontario reads:

“Born into bondage. Died in freedom. Helped hundreds walk the path between.”

Garrett refused to accept parole when the Confederacy formed in 1861. “I will not fight to preserve slavery,” he told the guards. He remained in prison until Union troops liberated it in 1863.

He moved north to Philadelphia, working for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and later teaching freedmen how to read and vote.

He died in 1877, buried under a simple headstone:

“Thomas Garrett — Sheriff of Albemarle County. Friend of Freedom. He saved 347.”

XII. The Forgotten War Within

Plantation owners rewrote the story. They painted Garrett as a madman corrupted by Northern propaganda, dismissed the escapes as “exaggerations,” and buried the truth beneath marble monuments to men like Ashford and Jefferson.

But the Black community remembered. The descendants of those 347 souls told the story again and again—of the sheriff who turned against his own kind, and the slave who taught him what justice meant.

Generations later, a small roadside marker appeared near Charlottesville:

“In 1849, Sheriff Thomas Garrett assisted in the escape of numerous enslaved people before being imprisoned. His actions dealt severe financial losses to local plantation owners and inspired abolitionists across the nation.”

No fanfare. No statue. Just truth carved in metal.

XIII. The Cost of Conscience

Today, Albemarle County markets its history through tours of Monticello and manicured plantations, where slavery is acknowledged but often softened. Yet the real story of the county’s collapse in 1849—the quiet war waged by a sheriff and a slave—still haunts the red clay soil.

They didn’t fire a shot. They didn’t lead an army. But they proved something terrifying to the masters of Virginia: slavery depended on obedience.

And once a single man refused to obey, the entire system trembled.

Thomas Garrett paid with his freedom. Daniel risked his life a hundred times over. Together, they destroyed a million dollars’ worth of human property and exposed the lie that slavery was invincible.

Their story asks the same question today that it did in 1849:

When the law and justice stand on opposite sides—

which one will you obey?

News

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis | HO!!

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis |…

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!!

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!! The…

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him! | HO!!!!

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him!…

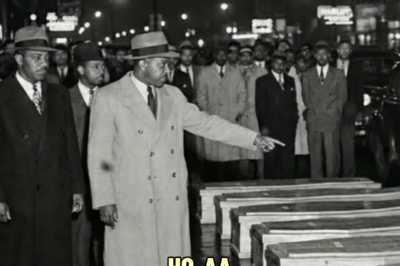

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!!

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!! For…

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!!

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!! That early fire, unpolished…

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!!

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!! The grass…

End of content

No more pages to load