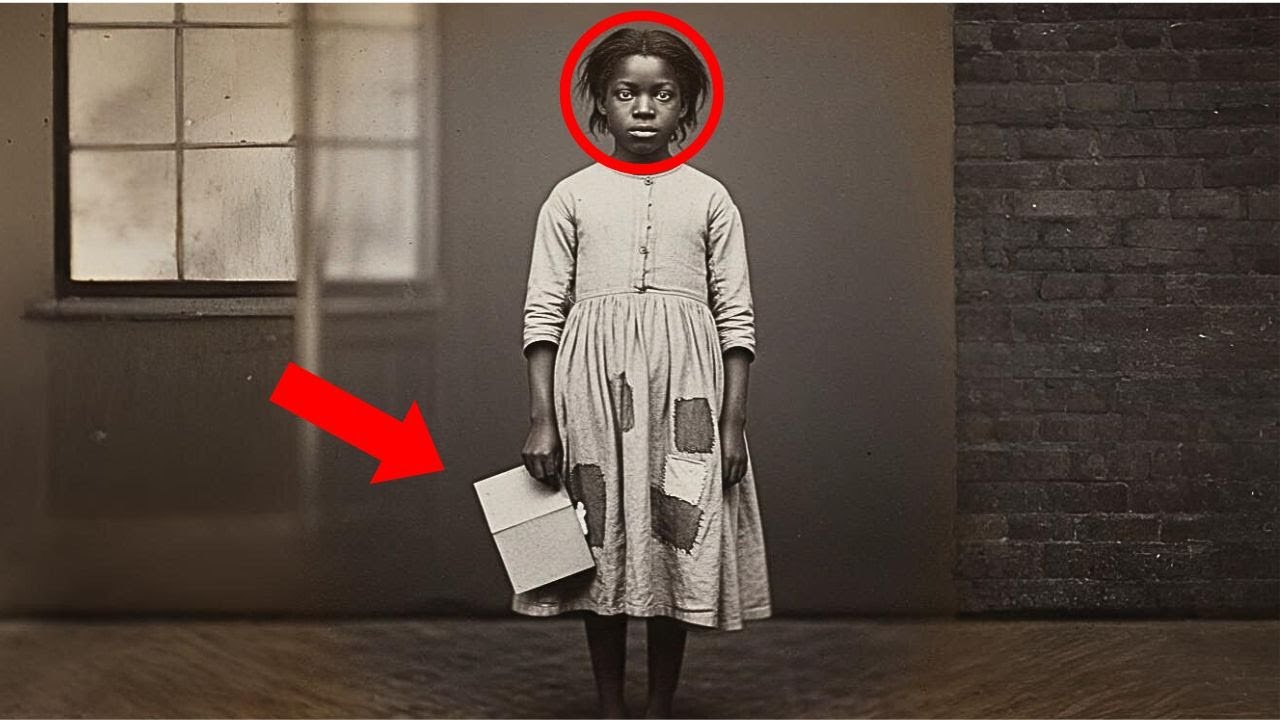

After Restoring the Photo, Experts Discovered What the Enslaved Girl Held — and Why She Never Smiled | HO!!

I. The Box in the Attic

The cardboard box had been sitting in Margaret Thornton’s attic in Richmond, Virginia, for as long as anyone could remember. It was the sort of box families inherit and never open—stuffed with yellowed letters, brittle newspaper clippings, and objects too sentimental to throw away yet too painful to confront.

In October of 2023, while preparing her late grandmother’s Victorian home for sale, Margaret finally lifted the lid. Inside, among the forgotten paper scraps and fading receipts, she found something unexpected: a small metal photograph, its surface eaten away by rust.

At first glance, it was almost unrecognizable. The metal plate—what experts later identified as a mid-nineteenth-century tintype—was scratched and corroded. But one thing remained heartbreakingly clear: the face of a young girl, staring into the camera with eyes filled with sorrow so deep it seemed to echo across time.

Margaret froze. The girl couldn’t have been older than nine or ten. She wasn’t smiling—none of the children from that era usually were—but this expression was different. It was absence. Grief. A gaze that understood something no child should ever have to know.

“Who is this child?” Margaret whispered to herself, holding the photograph under the weak light of the attic bulb. There was no name, no inscription. Just that haunting face and, she noticed, something clutched in the girl’s hand—a small, crumpled square of paper barely visible through the scratches.

It was enough to make her curious. Enough to change history.

II. The Call from Charlottesville

That night, Margaret photographed the tintype with her phone and posted it on a Civil War photography forum. Within hours, her inbox flooded with replies from collectors, historians, and amateur restorers. But one message stood out:

“This appears to be a significant historical artifact,”

wrote Dr. Patricia Hayes, professor of Visual History at the University of Virginia.

“The clothing and technique suggest early 1860s. If you’re willing, I’d like to examine this in person. There may be more to it than what’s visible on the surface.”

Margaret agreed immediately. She had no idea that her curiosity had just opened the first page of one of the most devastating stories of the Civil War era—hidden for 161 years inside a child’s silent photograph.

III. The Restoration

In a sterile lab in Charlottesville, Dr. Hayes and her colleague, digital restoration expert Michael Rodriguez, began the slow process of scanning the damaged image.

They’d worked on hundreds of nineteenth-century photographs before—portraits of soldiers, daguerreotypes of families—but something about this image unsettled them both.

“The deterioration is severe,” Michael murmured as the first scan appeared on his monitor. “Rust has eaten through at least forty percent of the emulsion.”

Dr. Hayes leaned closer. Even blurred by time, the child’s expression radiated unbearable sadness. “Children that age usually show curiosity, maybe fear,” she said. “But this… this looks like despair.”

They spent hours restoring it—layer by layer, pixel by pixel—carefully removing corrosion, digitally reconstructing the missing portions of the face and background. And then, late that night, as the image sharpened, they saw it: the small rectangle of paper in the girl’s hand.

“Michael,” Dr. Hayes whispered, “enhance that area.”

The screen zoomed in. The faint outline of handwriting began to emerge. Words. Ink. Legal script.

Michael’s brow furrowed. “There’s text here. Give me a few more hours.”

He worked in silence until nearly midnight. When Dr. Hayes returned, he was pale. “You need to see this,” he said.

On the monitor, the paper was now legible. Across the top, written in elegant nineteenth-century script, were three words that froze them both:

Bill of Sale

Below that, the rest of the text became clear:

“One Negro girl named Sarah, aged approximately nine years, sound of body and mind, sold this day of August 14th, 1862, for the sum of four hundred dollars.”

Dr. Hayes covered her mouth. “Oh, my God. She’s holding her own bill of sale.”

And at the bottom, faint but unmistakable, were two signatures—the seller’s name: Robert Thornton, and the buyer’s: James Hadfield.

Thornton. Margaret Thornton’s ancestor.

IV. The Weight of Discovery

When Dr. Hayes called Margaret the next morning, her voice was gentle but deliberate.

“I think the child in your photograph was named Sarah,” she began. “And the man who sold her shares your last name.”

There was silence on the other end. Then Margaret spoke quietly, almost to herself. “My family owned slaves,” she said. “I knew, in the abstract, that they probably did. But this—this is different. This is a face.”

Dr. Hayes asked if she could examine the Thornton family papers. Two days later, she found herself sitting in the library of the Richmond home, surrounded by ledgers, letters, and deeds dating back to the 1820s.

Inside a plantation record book marked 1862, she found it:

“Sarah, daughter of Ruth, age nine, house servant, valued at $450.”

A month later, the next line appeared:

“August 14th, 1862. Sold to James Hadfield of Lynchburg for $400. Buyer required immediate transfer. Mother Ruth remains property of this estate.”

The handwriting was calm. Precise. As if recording the sale of a horse, not a child.

Dr. Hayes closed the book and exhaled. “She was sold away from her mother,” she whispered. “That’s why she looked that way in the photo. That’s what we’re seeing.”

V. The Man Who Bought Children

Tracing James Hadfield led Dr. Hayes to Lynchburg, a city that had thrived during the Confederacy as a hub of tobacco, iron, and human trade.

At the Lynchburg Historical Society, archivist Thomas Green helped her search. Within minutes, the database filled with entries:

Hadfield had purchased seventeen enslaved children between 1860 and 1864.

He was a tobacco merchant, but his real business was darker. He ran what he called an “apprenticeship service.”

“He bought children under fourteen,” Green explained grimly, “then leased them out to factories and wealthy families under the pretense of ‘training.’ It was a front for profit. He’d rent them out, collect monthly fees, and keep legal ownership.”

Dr. Hayes scanned a newspaper clipping from 1863:

“Hadfield’s Apprenticeship Service — Industrious youth trained in domestic and mechanical arts. Inquiries welcome.”

Children, Dr. Hayes realized. Sold, leased, and catalogued like tools.

Among Hadfield’s records, one entry stood out:

“Aug. 15th, 1862 — One tint portrait of girl Sarah, with documentation. Cost: $2.”

He had ordered the photograph himself—the very tintype that would surface 161 years later in Margaret’s attic.

“She wasn’t photographed as a person,” Dr. Hayes said quietly. “She was photographed as proof of purchase.”

VI. The Girl in the Manning Household

The next name in Hadfield’s ledger was another clue:

“Sept. 1862 — Girl Sarah placed with Manning household for domestic service. Monthly fee $8.”

The Manning family had been industrialists in Lynchburg, owners of a textile mill that produced Confederate uniforms.

At the Virginia Historical Society, Dr. Hayes found their estate records—and, tucked between the ledgers, a diary kept by Catherine Manning, the family’s seventeen-year-old daughter.

Her entry from September 10th, 1862, stopped Dr. Hayes cold:

“A new girl has come to help Mother with the little ones. Her name is Sarah, though she will not answer to it. She is very young, perhaps my brother’s age, but there is no childhood in her eyes. She never smiles. She carries a paper in her apron and reads it often, though I cannot see the words. I think it must be a letter from home.”

Dr. Hayes knew what that paper was. The bill of sale.

A few months later, Catherine wrote again:

“Sarah still weeps at night. Father says she disturbs the household. They are sending her back to Mr. Hadfield.”

Returned like defective merchandise.

VII. The Warehouse Fire

Dr. Hayes followed the paper trail to Washington, D.C., and the National Archives, where she combed through the Freedmen’s Bureau records.

In a ledger dated November 1865, she found a desperate entry written in a trembling hand:

“Ruth, formerly property of R. Thornton Estate, Richmond, seeks information of her daughter Sarah, sold Aug. 1862 to James Hadfield of Lynchburg. Girl would now be approximately twelve years old. Mother wishes to reunite.”

There were three more entries like it. Ruth had survived the war and was searching for her child. But there was no record of a reunion.

Then Dr. Hayes found a Confederate newspaper report dated April 18th, 1863:

“Fire at the Hadfield warehouse — structure destroyed, losses estimated at $5,000. Three Negro children perished; others injured.”

Insurance records listed the loss as “three cattle (slaves).” No names.

For days, Dr. Hayes feared Sarah had died in that fire. But in a Freedmen’s Bureau testimony from 1866, she found a glimmer of hope:

“Spoke with girl named Eliza, age thirteen, formerly held by Hadfield. She reports that during the fire, a girl called Sarah, about ten, escaped through a window and fled toward the river. She carried a paper she always kept with her.”

Sarah had escaped.

VIII. The Road Home

If Sarah had survived, where would she go? Dr. Hayes could think of only one place—the Thornton plantation in Richmond, where her mother Ruth still lived.

But the journey would have been nearly 120 miles, through Confederate territory, across rivers and war zones.

Dr. Hayes turned to local genealogist Dorothy Freeman, an expert on Black family histories in Virginia. “If she tried to reach Richmond,” Freeman said, “she’d need help. Churches were the safest places then.”

Three days later, Freeman called back. “I found something,” she said.

At the First African Baptist Church in Richmond—a congregation founded by free and enslaved Blacks in the 1840s—archivists had preserved an 1863 journal kept by a deacon named Samuel Wright.

Dr. Hayes read the faded ink with trembling hands.

“A child came to us today, no more than ten years old, starving and exhausted. She carried a bill of sale showing she had been sold from the Thornton estate. She begs for her mother, Ruth. We sent word to the plantation but received no reply.”

Sarah had walked for three weeks, hiding by day and traveling by night, clutching the document that proved both her captivity and her identity.

IX. Too Late

For months, the church sheltered her, feeding her, trying to find her mother. Then, in August 1863, a new entry appeared in the journal—written in hurried, emotional script:

“Word came from the Thornton plantation. Ruth has died. We do not know how to tell the child.”

The next entry, dated August 14th, 1863—exactly one year after Sarah’s sale—read:

“We told her today. She did not cry. She only sat with that paper in her hands, staring at it. Sister Margaret says the child’s spirit is slipping away.”

Dr. Hayes had to stop reading. The parallels were too cruel: a girl holding her bill of sale, on the anniversary of her own sale, with nothing left to hope for.

X. The Girl Who Learned to Write

But the church journal continued.

In November 1863:

“The child Sarah has begun to speak again. She asks to learn reading and writing. Sister Margaret teaches her in secret, though the laws forbid it.”

In 1864:

“Sarah now helps the younger ones with their letters. She learns quickly, with purpose I cannot explain.”

And finally, in June 1865, after Richmond fell and the war ended:

“Sarah says she will keep her mother’s name. She no longer defines herself by that paper. She will help others find what she could not.”

Dr. Hayes wept as she read the last lines. The child who had been sold, photographed as property, had survived—and become a helper for others.

XI. The Legacy of Sarah Freeman

Tracing Sarah’s later life was painstaking, but with help from church and census records, Dr. Hayes built a full portrait.

In 1868, Sarah married a carpenter named Joseph Freeman—adopting the name that would appear in family trees generations later. Together they had four children, all of whom she taught to read by age five.

She worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau for three years, helping other families find loved ones separated by slavery. In an 1870 letter preserved in the Bureau’s files, she wrote:

“I know your pain because I lived it. I carried that paper because it proved I existed. Now I carry my mother’s love instead. Do not give up. Love is stronger than the documents that tried to divide us.”

Sarah lived until 1921. She was sixty-eight years old when she died—grandmother to seventeen, matriarch of a family that would span the American century.

But according to oral history passed down through her descendants, she never discarded the bill of sale.

Once a year, on August 14th, she would gather her children and grandchildren and read it aloud.

“This paper once said I was worth four hundred dollars,” she told them. “But I am worth everything—my mother’s love, my freedom, my voice. Never let anyone tell you what you’re worth.”

XII. The Exhibition

In March 2024, the University of Virginia unveiled an exhibition titled “The Girl Who Would Not Smile.”

At its center was the restored tintype—Sarah’s photograph—displayed beside her original bill of sale, Ruth’s letters, the Manning diary, and the church journal that documented her survival.

A contemporary artist had painted a large portrait imagining Sarah as an adult—strong, luminous, smiling.

On opening day, forty-three of her descendants stood before that portrait, five generations gathered in one room. Among them was James Freeman, Sarah’s great-great-grandson and a retired schoolteacher.

He spoke softly, his voice steady but full of emotion.

“My ancestor never smiled in that photograph because she understood exactly what was happening. She was being recorded as property. But she lived to reclaim her name, her story, and her worth. That photograph tried to define her as merchandise. We define her as a hero.”

Margaret Thornton stood beside him, tears in her eyes. She had donated the tintype and funded a scholarship in Sarah’s name—for students studying African-American history and archival restoration.

“I thought I was cleaning out an attic,” she said quietly. “Instead, I uncovered a life.”

XIII. The Photograph That Spoke

Today, the restored image hangs in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. Beneath it is a simple inscription:

Sarah Freeman (c.1853–1921)

Sold at age nine. Survived. Reunited families. Taught generations. Never forgot. Never surrendered.

Below the inscription is a quote from her 1870 letter:

“I carried that paper because it proved I existed. Now I carry my mother’s love instead.”

Visitors stand in silence before it. Some weep. Some simply stare, trying to comprehend how something so small—a photograph, a slip of paper, a name—can contain an entire world of pain and survival.

In the end, the girl who never smiled became more than a tragic image. She became proof of endurance, of memory stronger than erasure, of a lineage that refused to vanish.

What was once a photograph of ownership has become a monument to freedom.

And if you look closely at that restored image—past the rust, past the century of silence—you can almost see it:

the faintest hint of light in Sarah’s eyes, as if somewhere inside, even then, she already knew she would outlive the men who sold her.

News

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis | HO!!

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis |…

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!!

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!! The…

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him! | HO!!!!

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him!…

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!!

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!! For…

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!!

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!! That early fire, unpolished…

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!!

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!! The grass…

End of content

No more pages to load