America’s Darkest DNA Secret Finally Revealed The Truth About the Melungeons | HO!!

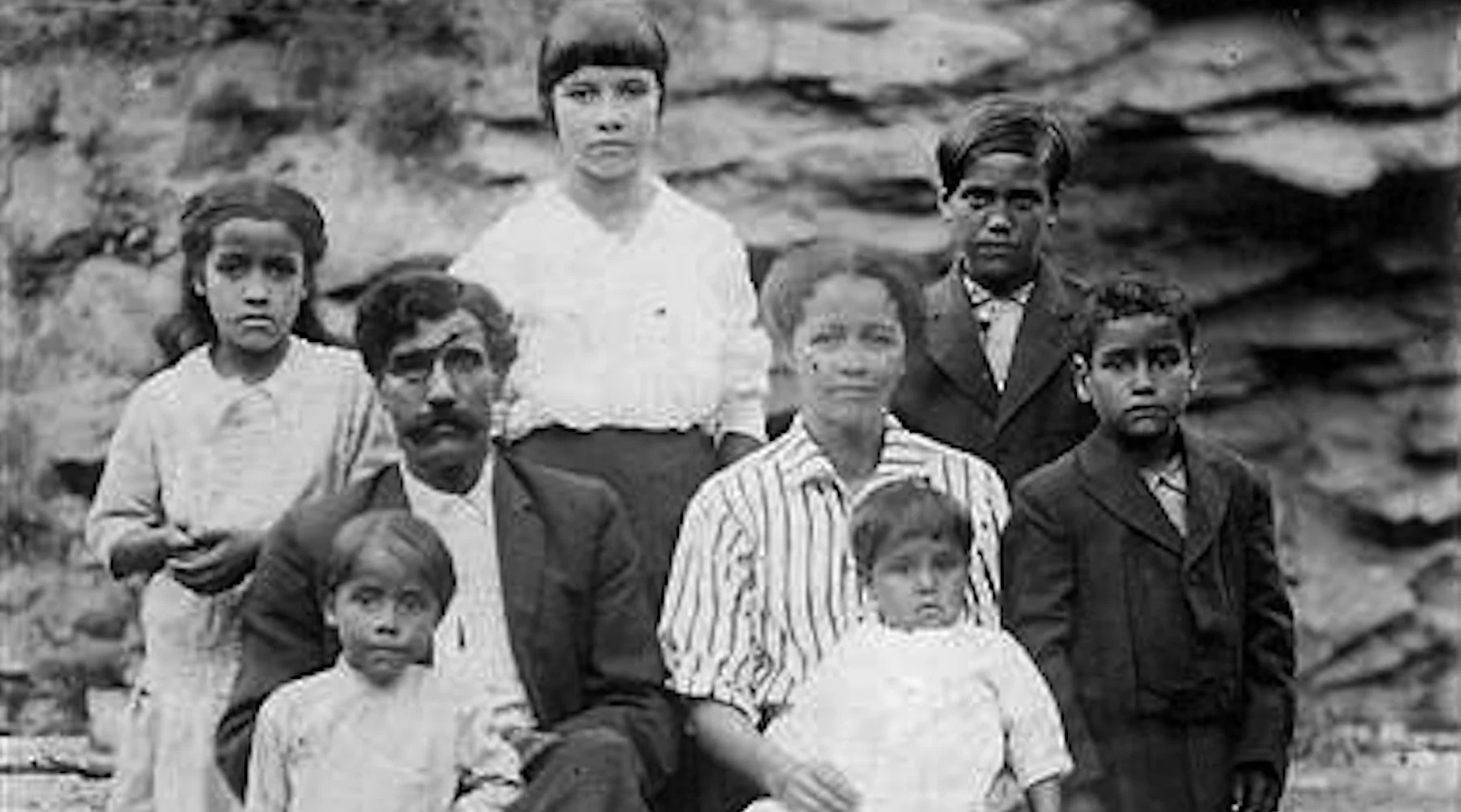

For centuries, a shadowy people lived in the hollows and ridges of Appalachia, neither white nor black, neither fully accepted nor entirely erased. They called themselves Melungeons—or, more often, called themselves nothing at all. To outsiders, they were a riddle: olive-skinned, straight-haired, with surnames like Collins, Goins, and Gibson, and stories that never quite added up.

Feared, shunned, and mythologized, the Melungeons unsettled the rigid racial hierarchies of early America. But it would take the arrival of modern DNA science to finally unravel their secret—a truth far stranger than any legend ever told.

A People Out of Place

When we think about the founding of the United States, we imagine clear lines: black and white, enslaved and free, native and settler. The Melungeons shattered those binaries. In colonial Virginia, North Carolina, and later Tennessee, they appeared in court records as “mulatto,” “free person of color,” “Portuguese,” or left blank altogether.

Their ambiguous status bred suspicion and exclusion. They were taxed differently, barred from certain rights, and sometimes prosecuted for marrying whites under anti-miscegenation laws. But no consistent label could define them.

By the late 1700s, as slave laws tightened and racial codes hardened, these mixed families—Collins, Gibson, Goins, Mullins—migrated westward into the Appalachian frontier. The mountains offered refuge, but also isolation.

There, the Melungeons created insular communities, intermarrying and clinging to survival in places like Newman’s Ridge and Blackwater Valley, where the government seldom intervened and questions about ancestry could be answered with silence.

Rumor as Armor

With their very existence threatening the racial order, the Melungeons learned to weaponize stories. They claimed descent from Portuguese sailors shipwrecked on the Carolina coast, or from Turkish captives, or from the lost English colony of Roanoke. Some even whispered of Sephardic Jews fleeing the Inquisition.

These tales, repeated in courtrooms and church records, were not just folklore—they were survival strategies in a society where a single drop of African blood could mean the loss of land, liberty, or children.

In the South, ambiguous ethnic labels like “Black Dutch” or “Black Irish” allowed Melungeon families to blend in, move across county lines, enlist in militias, and sometimes vote. The stories placed their origins outside the plantation economy, sidestepping the implications of African ancestry in a slave society. Yet, every legend was a shield against a system designed to erase them.

The Power—and Price—of Passing

As state laws sharpened racial definitions in the 1800s, Melungeons faced stark choices. Some vanished into whiteness, changing names, moving towns, and severing ties with darker-skinned relatives. Others kept to the mountains, preserving their mixed identity in private, passing down oral traditions and intermarrying within familiar surnames.

Census records reveal the shifting sands of racial classification: a family listed as “mulatto” in 1850 might be “white” in 1860, depending on who was asking, who was answering, and how much sun they’d caught that summer.

The stakes were high. Being reclassified as non-white could mean losing property, the right to vote, or even custody of children. For many, the safest way to survive was to erase the past, to let genealogical silence become a family inheritance. By the time 20th-century ethnographers arrived, the Melungeons were already a mystery—unique dialects, unfamiliar surnames, and physical traits that defied easy categorization.

The Law as Weapon

Long before DNA could reveal the truth, the law had already decided what people were allowed to be. In the infamous case of Martha Simmerman v. State of Virginia (1874), a woman of mixed ancestry was prosecuted for marrying a white man. Her racial status was determined not by fact, but by appearance, reputation, and hearsay. In Tennessee, Jacob Perkins was denied the right to vote or own land based solely on local suspicion, not evidence.

Behind the scenes, bureaucrats like Walter Plecker, Virginia’s registrar of vital statistics, waged a quiet war on racially ambiguous communities. From 1912 to 1946, Plecker rewrote birth and death certificates, recategorizing thousands as “Negro” based on his own taxonomy.

The Racial Integrity Act of 1924 codified the infamous “one drop rule,” stripping Melungeon families of rights, property, and even their names. Generations vanished from white records, reappearing as “colored” or “other”—the result was generational trauma and deliberate silence.

DNA: The End of the Mystery

For over 200 years, Melungeons eluded definitive classification, protected by myth and geography. But in the early 21st century, science came knocking. In 2002, researchers from the University of Virginia and Middle Tennessee State University launched the first comprehensive DNA study of Melungeon families.

Using mitochondrial DNA, Y-chromosome analysis, and autosomal markers, they tested descendants of the Collins, Goins, and Gibson families—people who could trace their presence in Appalachia back over two centuries.

The results, published in 2011 in the Journal of Genetic Genealogy, upended centuries of myth. The Melungeons were not descended from Portuguese sailors, Turkish prisoners, or lost English colonists. Instead, their ancestry was tri-racial: primarily a mix of European men, sub-Saharan African men, and Indigenous American women.

The pattern was painfully familiar: powerful white men fathering children with enslaved African or Native women—a structure found throughout the South, but rarely acknowledged so clearly by its descendants.

Some Melungeon paternal lines traced directly back to Africa, not via recent immigration or the Caribbean, but through the colonial American South. Many maternal lines were Indigenous, confirming long-held oral traditions, but not to the extent earlier legends claimed. Portuguese ancestry, statistically, was negligible.

A Reckoning—And Resistance

The DNA findings should have ended the debate. Instead, they ignited a firestorm. For many Melungeon descendants, the results were liberating—a chance to reconnect with silenced parts of their heritage. For others, they were an unwelcome truth. Online forums and genealogy groups erupted in denial and debate. Some accused researchers of bias; others questioned the sample size or methodology. Many simply refused to accept the findings.

The pushback echoed a national pattern: just as America often resists confronting its own racial past, so too did many Melungeon descendants resist the implications of their DNA. The story was never just about genetics—it was about the lie of racial purity, enforced and internalized for centuries.

Yet, not all responses were defensive. For younger generations and scholars, the findings were a chance to embrace a fuller, more honest identity. Family trees were re-examined, and long-suppressed stories of African and Indigenous ancestors finally given voice. Some communities began organizing cultural events acknowledging their tri-racial past, rather than just their more palatable European roots.

A Mirror for America

The Melungeon saga is more than an Appalachian curiosity. It is a case study in how America’s darkest anxieties about race were written into law, whispered through families, and only recently overturned by the blunt force of genomics. From the first colonies onward, Europeans, Africans, and Indigenous people intermarried far more freely than later statutes allowed. Dozens of similarly mixed districts across the South went through parallel cycles of suspicion, reclassification, and silence.

The lesson is clear: racial categories are political inventions, not biological truths. They collapsed the moment DNA evidence entered the courtroom of public opinion. By confronting those inventions, the Melungeon story reframes debates about citizenship, reparations, and who gets to write America’s official narrative.

If one mountain community could hide in plain sight for two centuries, how many other lost histories wait in courthouse basements or in the untested chromosomes of present-day Americans? The truth about the Melungeons is not just theirs—it is a mirror held up to a nation built on the fiction of racial purity.

As genetic testing becomes routine and archives go online, more uncomfortable facts will surface. The question is not whether more secrets exist—history suggests they do—but whether America is finally ready to confront them.

News

The Master Who Forced His Three Daughters Into a Dark Pact With His Strongest Slave — Georgia, 1852 | HO

The Master Who Forced His Three Daughters Into a Dark Pact With His Strongest Slave — Georgia, 1852 | HO…

The Impossible Mystery of the Witch Slave Who Cured 33 People, Was Sentenced to ʙᴜʀɴ, and Vanished | HO

The Impossible Mystery of the Witch Slave Who Cured 33 People, Was Sentenced to ʙᴜʀɴ, and Vanished | HO At…

The Impossible Mystery of the Witch Slave Who Cured 33 People, Was Sentenced to ʙᴜʀɴ, and Vanished | HO

The Impossible Mystery of the Witch Slave Who Cured 33 People, Was Sentenced to ʙᴜʀɴ, and Vanished | HO At…

‘That’s My Ex-Girlfriend!’ – Mountain Man Bought The ғᴀᴛ Girl at Auction, Found His Lost Love | HO

‘That’s My Ex-Girlfriend!’ – Mountain Man Bought The ғᴀᴛ Girl at Auction, Found His Lost Love | HO Milbrook, Virginia…

Enslaved Mother Had Triplets — Was Forced to Abandon Two Children to Save the Light One (1847) | HO

Enslaved Mother Had Triplets — Was Forced to Abandon Two Children to Save the Light One (1847) | HO In…

‘Daddy, That’s Mommy—The $1 ғᴀᴛ Girl Nobody Wanted’ Mountain Man’s Daughter Found Her Perfect Mother | HO

‘Daddy, That’s Mommy—The $1 ғᴀᴛ Girl Nobody Wanted’ Mountain Man’s Daughter Found Her Perfect Mother | HO Silverton, Colorado —…

End of content

No more pages to load