Before He D!ed, James Brown Revealed 7 Black G@y Singers He Hated Most | HO

In the mythology of American music, James Brown stands as the Godfather of Soul — the unshakable patriarch who turned gospel into groove and transformed rhythm into a weapon of Black pride. But behind the public image of power and control, Brown harbored a darker obsession: a deep, consuming hostility toward the queer men who, in their own ways, were reshaping Black music alongside him.

By the 1970s and ’80s, as America wrestled with civil rights, sexual liberation, and the AIDS crisis, funk became a battleground for identity itself. And James Brown, who built his career on discipline, masculinity, and moral order, began to see certain artists not just as rivals — but as threats to the very soul of his creation.

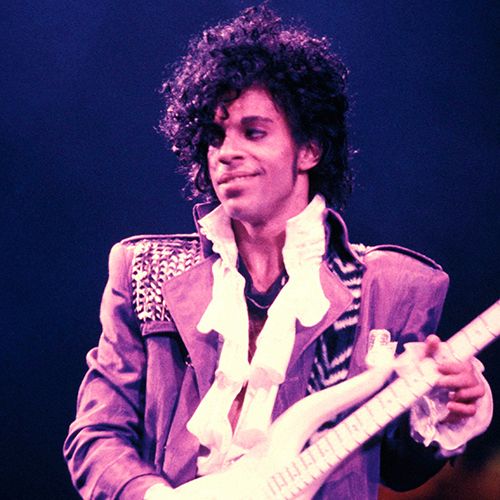

Prince: The Beautiful One Who Dared

The tension ignited in 1983, at the Beverly Theater in Los Angeles. Brown invited Michael Jackson onstage mid-show — a moment of mutual admiration. Then Jackson, unprompted, called out to the audience: “Prince, come up here with me.”

Prince sauntered onto the stage in heels and lace, tuning a guitar as if in defiance. His performance — discordant, flamboyant, unbothered — was everything Brown was not. By the next morning, he was livid. “Funk has turned into a toy for gender-benders,” he reportedly spat.

To Brown, Prince’s androgyny wasn’t artistry. It was rebellion — an aesthetic coup. And as Prince’s Purple Rain conquered the charts, Brown saw a moral collapse disguised as innovation.

Sylvester: The Saint of the Disco Church

Before Prince, another figure had already tested Brown’s patience. Sylvester, the gospel-trained falsetto who became a disco icon, strutted across stages in sequined gowns and platform heels. For queer Black America, he was liberation incarnate. For Brown, he was heresy.

He couldn’t fathom how a man who wore lipstick could be praised by white critics as “the Black David Bowie.” Sylvester’s open embrace of queerness — and the adoration it earned him — mocked everything Brown thought funk stood for: sweat, discipline, and masculine power. When Sylvester headlined New York Pride in 1983, Brown canceled a nearby show rather than “play near where that guy is singing.”

Little Richard: The Original Sinner

But Brown’s unease with queerness stretched back decades — to Little Richard, the man who arguably invented the stage Brown later ruled. In the 1950s, Richard’s pompadour, eyeliner, and ecstatic screams scandalized America. Brown, raised in the church, called him “a pervert in performer’s clothing.”

Even after Richard’s religious conversions and retractions, Brown couldn’t forgive him. The real offense, he told bandmates, was that Richard “changed gender like underwear” — that his contradictions blurred the line between salvation and sin.

Rick James, Billy Preston, Sly Stone, George Clinton: The Descent into Chaos

By the 1980s, Brown’s list of enemies had grown longer — and more complicated. He dismissed Rick James as “a man who hurts people with music” after James’s well-publicized arrests for sexual assault. He called Billy Preston, the gentle organist known as the “fifth Beatle,” a “dangerous fake,” privately citing Preston’s own criminal cases and hidden sexuality as proof of rot within the industry.

Sly Stone’s acid-fueled collapse and George Clinton’s psychedelic gender-bending theatrics only deepened Brown’s paranoia that funk — his proud, Black, disciplined creation — had fallen into chaos.

The Man Who Couldn’t Bend

By the time Brown died in 2006, funk’s center had shifted far beyond his control. Artists like Prince, Sylvester, and George Clinton had rewritten what freedom could look like onstage. They blurred the boundaries between male and female, sacred and profane, Black and universal — and in doing so, they liberated generations of musicians Brown had hoped to command.

What endures isn’t Brown’s anger, but the irony: that the Godfather of Soul, who once taught America how to move, could never learn to move with the times. His war against queer funk wasn’t just personal — it was the last stand of a man terrified of the future his own music had unleashed.

News

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO “How,” he…

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO

Judge’s Secret Affair With Young Girl Ends In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 Crime stories | HO On February 3, 2020, Richmond Police…

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… | HO

I missed my flight and saw a beautiful homeless woman with a baby. I gave her my key, but… |…

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know | HO

Husband 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 His Wife After He Discovered She Did Not Have A 𝐖𝐨𝐦𝐛 After An Abortion He Did Not Know…

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO

1 HR After He Traveled to Georgia to Visit his Online GF, He Saw Her Disabled! It Led to 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫…

End of content

No more pages to load