Black boy was found with 2 missing white girls. The detective was shocked to discover that… | HO!!

PART I — THE DISCOVERY

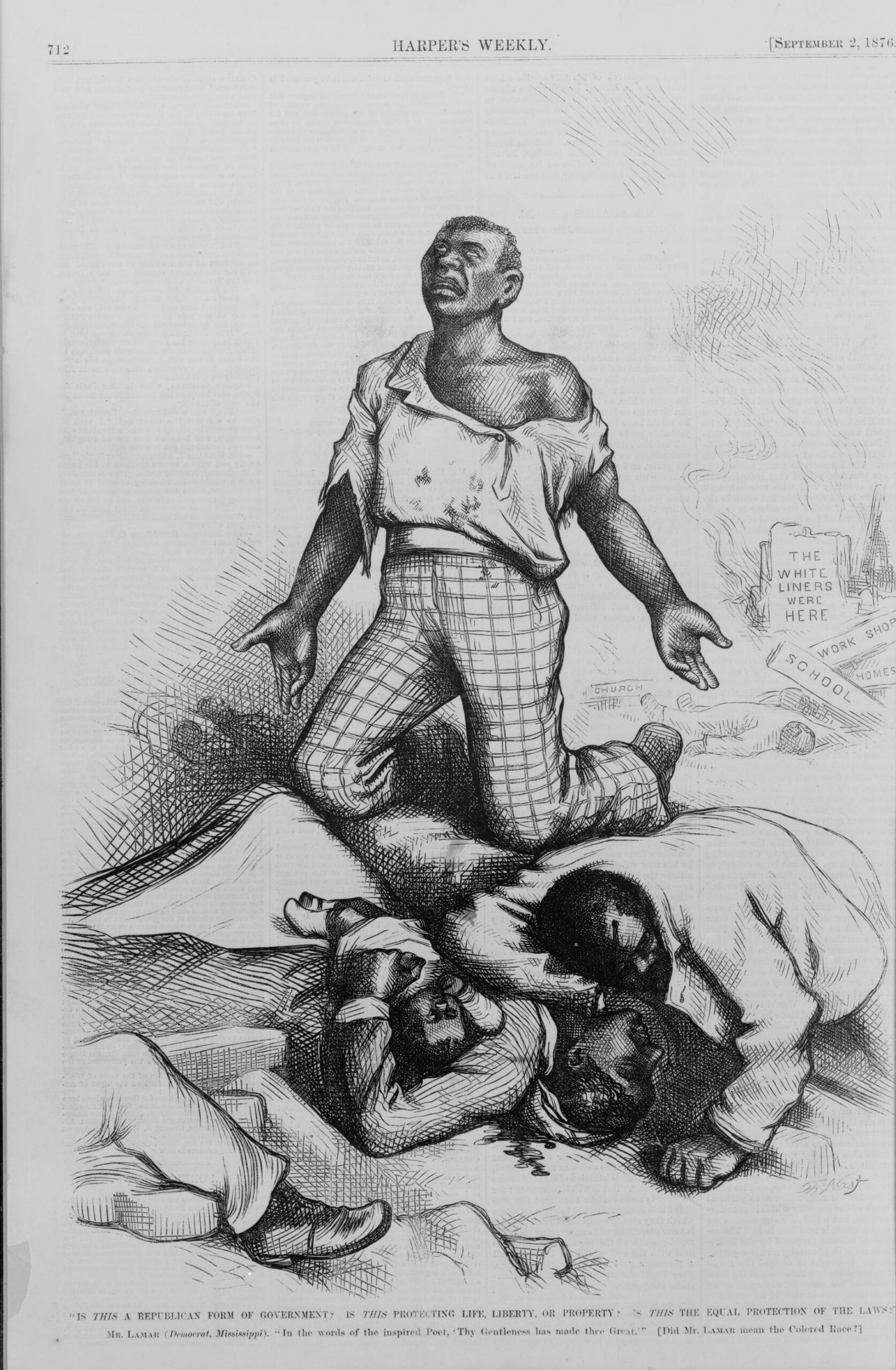

On the night of November 18, 1875, in a remote corner of rural Mississippi, a local landowner discovered a scene that would ignite one of the most volatile investigations of the Reconstruction era. Near a dilapidated timbershed on what had once been the Hollow Bend plantation, a twelve-year-old Black boy was found kneeling in the mud, clutching the bodies of two white girls reported missing hours earlier.

The landowner who made the discovery described the boy as “silent, trembling, and soaked to the bone.” When he was ordered to step away, he did not move. When men shouted at him, he did not respond. He continued cradling the girls as if refusing to acknowledge their deaths. Within minutes, the landowner sent a rider for law enforcement. Within an hour, word spread through the county that a Black child had murdered two white girls.

By the time Detective Thomas Reed arrived from the county seat, a mob had already begun to form.

Reed, 39, had served as a county detective for seven years. He had handled homicides, property crimes, arsons, and countless disputes between white landowners and the freed Black laborers who now comprised most of the region’s workforce. He had never once intervened in a lynching. He had watched bodies appear on bridge timbers at dawn and recorded these deaths as “unknown assailants,” just as every lawman in the county did to preserve his position.

What he saw that night did not match the narrative circulating among the men gathered with rope in hand.

The girls—nine-year-old Catherine Morrison and her seven-year-old sister, Eleanor—displayed unmistakable signs of drowning. There were no stab wounds, no trauma, no marks of struggle. Their clothing was intact. Their bodies were clean. Most inexplicably, the water found in their lungs was clear, free of the silt and debris characteristic of the region’s streams.

There was no river nearby. No pond. No flooded ditch. The nearest water source lay half a mile away.

The boy, known only as Eli, gave no explanation beyond a single phrase he repeated in a nearly inaudible whisper:

“I tried to make them breathe again.”

The sheriff ordered the children’s bodies removed and instructed two men to pry the girls from Eli’s arms. It required force. The boy refused to let go.

An Immediate Accusation

Within an hour, the county’s attorneys, church leaders, and prominent landowners knew every detail—except for the ones that would complicate the narrative. The story traveled with remarkable speed:

A Black boy killed two white girls. Case closed.

In Reconstruction Mississippi, that was more than enough to justify a lynching.

But Reed, trained to observe inconsistencies, noticed a detail that unsettled him: the complete absence of any sign of violence. Nothing suggested malicious intent. Nothing supported the assumption of murder.

More troubling still was the clarity of the water in the girls’ lungs.

Clear water did not come from the nearest creek. Clear water suggested a spring.

And there was only one spring-fed stream in the area: a narrow channel behind Calvary Baptist Church.

Reed knew the place well. A mile from the Morrison property, the stream had been used for baptisms since before the Civil War. Its water was unusually clean—a rarity in the muddy riverlands.

It was also a location that Black children like Eli avoided at all costs. Calvary Baptist was the center of white civic power, not a place where a Black child would wander freely.

Something about Eli’s explanation—that the girls had been in the water behind the church—was immediately at odds with the distance and terrain between the two sites. If he had carried the bodies all the way to the shed, he would have had to make multiple trips across rugged ground in the dark.

To Reed, the physical evidence suggested many things. But none of them pointed to a 12-year-old killer.

The Interrogation

By 1 a.m., Eli was shackled in the county jail beneath the courthouse. He had been silent for hours, speaking only when redirected. In the interrogation room sat three men: Sheriff William Garrett, County Attorney Preston Roor, and Reed.

Attorney Roor opened the questioning.

“You drowned those girls. Admit it now and save us all time.”

Eli’s voice was barely audible. “I found them in the water. I pulled them out. I tried to help them breathe.”

“What water?” Reed asked.

“The one behind the church. The clean water.”

“How did you get the girls from the church to the shed?” Roor demanded.

“I carried them. One at a time. I just kept going.”

The timeline was impossible. The medical examiner estimated the girls had died between 6:00 and 7:30 p.m. The bodies were found at 8:15. Carrying two children across a mile of uneven terrain in that time frame was implausible even for a grown man, let alone a malnourished child.

“What were you doing near the church?” Roor asked.

“There’s good water there,” Eli said. “And you can hear the singing on Sundays.”

Roor leaned forward. “You were watching white children.”

“No, sir.”

A Medical Report That Changed Everything

At 3 a.m., Dr. Samuel Pritchard completed his examination. His findings were stark:

Cause of death: drowning

No signs of assault

No signs of struggle

Clean water in lungs

Estimated time of death: early evening

No evidence of violence

Pritchard added one more comment—one that would have been irrelevant if not for the racial politics of the era:

“No sexual assault. Had there been, the boy would already be dead.”

It was a statement of fact, not hyperbole.

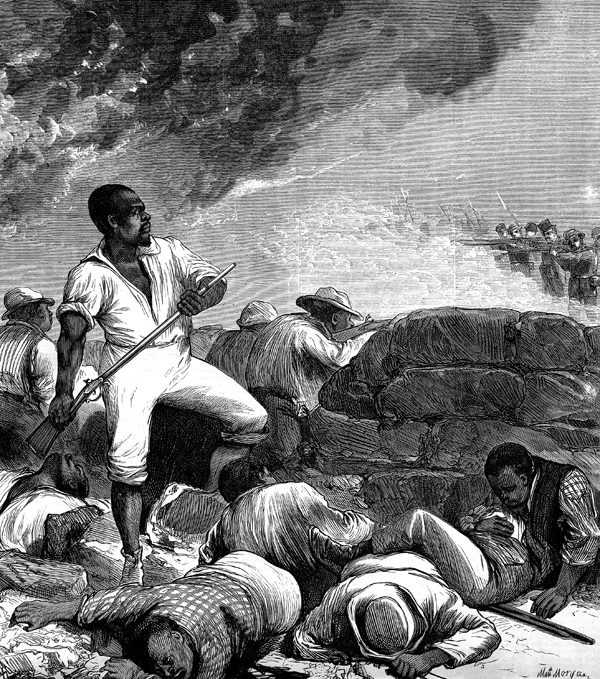

A Mob Forms

By dawn Friday morning, the courthouse lawn filled with men demanding immediate execution. They shouted for the sheriff to release the boy to them. The cries were familiar echoes of similar incidents across the South.

Anything resembling due process was considered an indignity.

Reed and Sheriff Garrett stood on the courthouse steps.

“We will not hand the boy over,” Garrett announced. “Anyone attempting to breach this courthouse will be shot.”

It was a temporary victory. The crowd dispersed, but not peacefully. Men left muttering about taking “proper action” if the courts failed to deliver swift justice.

Reed understood the message clearly.

He had less than 48 hours before the mob returned.

The First Break

Late Friday morning, Reed visited the spring behind Calvary Baptist Church. The ground was undisturbed. No signs of struggle. No footprints. No clothing fragments.

But near the streambed, he found wagon tracks—fresh ones—leading toward the water and back to the main road.

Someone had driven a wagon close to the stream that evening.

Someone with a wagon—and authority—had likely been the last adult to see the Morrison girls alive.

Reed’s first inclination: interview their parents.

Unanswered Questions at the Morrison Home

James and Clara Morrison maintained their daughters were supposed to have been at a sewing lesson at the schoolhouse.

But the lesson had been canceled.

Neither parent knew where the girls had been for four hours before their deaths.

Clara insisted the children had never interacted with Eli.

“We don’t socialize with Negroes,” she said. “They would have had no reason to know that boy.”

Reed noted the fear behind her certainty. Something was wrong—but he could not yet put his finger on it.

What he did not know was that someone else had seen the girls at the stream that evening.

And that someone was about to risk her life to tell him.

PART II — THE COVER-UP

On Saturday morning, as Reed returned to the courthouse, a woman approached the doorway hesitantly. Her name was Emma Whitfield, a Black laundress who lived near the church grounds.

“I need to tell you something about Thursday evening,” she whispered.

Reed led her into the hallway.

“I saw the reverend’s wagon by the stream,” she said. “And I saw two white girls get into the back.”

Reed stared at her. “You’re sure?”

“Yes, sir. Couldn’t mistake that brass fitting on the wagon.”

The girls had entered the vehicle willingly. They knew the reverend.

“Why didn’t you say this before?” Reed asked.

Emma’s eyes filled with fear. “Because accusing a white preacher gets people like me killed.”

Reed understood. Witnesses in the Reconstruction South faced a simple equation: truth often equaled death.

A Revered Figure with Something to Hide

Reed interviewed the deacons who had allegedly met with Reverend Samuel Fletcher on Thursday evening. All insisted Fletcher had been home preparing Sunday’s sermon.

But their rehearsed statements raised suspicion. The deacons’ accounts matched too perfectly. Their timeline too neatly aligned.

Reed returned to the stream and re-examined the wagon tracks. Fifty yards from the water, he found a fragment of blue ribbon snagged on a branch. Catherine Morrison had worn such ribbons.

The evidence was mounting.

But proof in a legal sense required something more tangible.

The Groundskeeper’s Testimony

On Monday morning, the second witness came forward.

His name was Samuel, a groundskeeper at Fletcher’s residence.

Samuel’s voice shook as he spoke.

“The reverend was teaching white children to swim in that stream,” he said. “Said it was for baptism. But parents told him to stop after one boy nearly drowned.”

Reed froze.

Swimming lessons.

Secret ones.

Ending in disaster.

“They kept letting him teach the Morrison girls because their daddy paid extra,” Samuel continued. “And Thursday evening, he came home soaked. Said there’d been an accident. Burned his clothes.”

“Do you have proof?” Reed asked.

Samuel reached into his pocket. “Found this near where he burned his clothes.”

A brass button with the initials S.F.

It was the first physical evidence placing Fletcher at the scene.

But Samuel refused to testify in court.

“They’ll hang me if I speak,” he whispered.

The Story Fletcher Told

When confronted, Reverend Fletcher denied everything.

“I was home all evening,” he insisted. “This is a slanderous accusation built on Negro lies. I will not dignify it further.”

Behind his calm tone was unmistakable threat.

“You’re playing a dangerous game, detective,” he warned. “There are forces in this county that will not tolerate attacks on church leadership.”

The forces he referred to were not theological.

They were political.

A Battle of Narratives

County Attorney Roor reviewed Reed’s findings and dismissed them outright.

“You have testimony from two Negroes, one of whom refuses to appear in court,” he said. “You have a button that could have been dropped anytime. Meanwhile, a Black boy was found holding two dead white girls.”

Roor leaned back.

“The community requires resolution. A quick trial. A legal execution. That is stability. Everything else is chaos.”

To Reed, it was a naked admission.

The county was willing to execute an innocent child to preserve white comfort.

The Trial

The trial was scheduled for Thursday—barely a week after the girls’ deaths. Reed knew courts moved quickly in cases involving alleged crimes by Black defendants, but the speed of this trial was extraordinary even by Reconstruction-era standards.

Jury selection took less than an hour. Twelve white men, all landowners.

Reed took the stand. Under oath, he testified truthfully:

The physical evidence contradicted the prosecution’s theory.

Witnesses placed Fletcher at the stream.

The timeline made Eli’s guilt impossible.

The baptismal cross found in the mud belonged to Eleanor.

The button belonged to Fletcher.

The courtroom erupted.

Roor accused Reed of misconduct. Judge Timothy Timmons restricted the detective’s testimony, ruling key statements as hearsay. Fletcher took the stand and denied all allegations.

The jury deliberated for seventeen minutes.

They returned a verdict of guilty.

An Execution Scheduled

The judge set sentencing for Friday and execution for Saturday at dawn.

Reed visited Eli that afternoon. The boy accepted his fate.

“They’ll kill me,” he said. “But at least you tried.”

Reed, stripped of authority, suspended from duty, had no remaining legal avenues.

A Midnight Decision

Reed attempted to stop the execution by appealing directly to Judge Timmons, who refused.

“A Negro convicted of murdering white children will be executed,” Timmons said. “That is the law.”

It was not law. It was the weaponization of law.

The machinery of racial control.

The Father’s Confession

Late that night, James Morrison—the girls’ father—arrived at Reed’s door.

“I need to tell you something,” he whispered.

He confirmed everything:

Fletcher had indeed been teaching the girls to swim.

Morrison had paid him privately.

His wife had not known.

And the lessons continued after parents demanded they stop.

“I want to testify,” Morrison said. “But Fletcher told me if I speak, he’ll ruin me. Ruin my business. My marriage.”

Morrison began to cry.

“I’m a coward. But the boy is innocent.”

Reed realized the truth: only one thing could save Eli.

A public confession.

From the victim’s own father.

But Morrison was too afraid—until the moment the rope was placed around Eli’s neck.

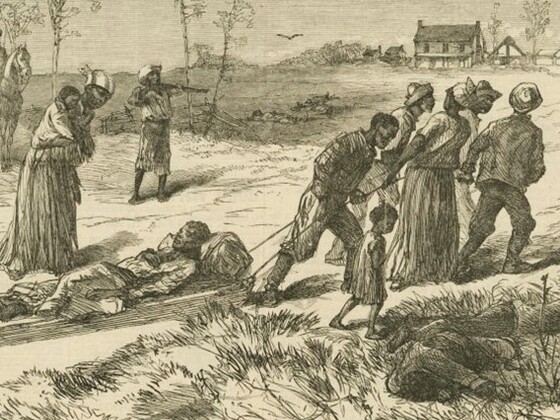

PART III — THE MORNING OF THE EXECUTION

At dawn on Saturday, December 4, 1875, a crowd of more than 300 gathered outside the courthouse. The gallows had been erected overnight.

Reverend Fletcher delivered a prayer framing the execution as “God’s will.”

Eli, shackled and pale, stood silently as the noose was placed around his neck.

Judge Timmons raised his hand to begin the execution.

Then a voice cut through the cold morning air.

“STOP!”

James Morrison pushed through the crowd and climbed onto the platform.

“That boy is innocent,” he shouted. “I have testimony that proves it.”

A ripple of shock moved through the crowd.

Morrison declared publicly that:

Fletcher had taken the girls to the stream.

Fletcher had taught them to swim.

Fletcher had panicked when they drowned.

Eli had tried to save them.

A cover-up had taken place.

The executioner stepped back.

Sheriff Garrett removed the noose.

Judge Timmons attempted to regain control, but the crowd’s consensus—necessary for any public execution—had fractured.

He ordered Eli returned to jail “pending review.”

The Collapse of Fletcher’s Alibi

Over the next two weeks:

Two deacons recanted their statements.

Fletcher’s wife confirmed his wet clothes and the burning of garments.

The brass button matched Fletcher’s coat.

Morrison provided sworn testimony.

Faced with overwhelming evidence, the county negotiated an informal resolution:

Charges against Eli would be dropped.

No formal exoneration would be issued.

Fletcher would quietly leave the state instead of facing trial.

No one in authority admitted wrongdoing.

Aftermath

Eli was freed shortly before Christmas. He had no family, no home, and no compensation. Reed gave him $40 and watched the boy walk north.

Fletcher relocated to Arkansas, founded a new church, and lived unblemished until his death in 1893.

James Morrison divorced his wife, moved to Texas, and spent the remainder of his life questioning the morality of his silence.

Reed left law enforcement, wrote a manuscript documenting the case, and buried it beside the dried stream behind Calvary Baptist Church.

In 1925, road workers discovered the manuscript. In 1930, a historian published a monograph based on Reed’s work.

It never reached a wide audience.

The Historical Record

Catherine and Eleanor Morrison’s graves remain in the expanded cemetery of Calvary Baptist Church.

Eli’s final fate is unknown.

He appears in no census. No employment rolls. No burial records. His life slips from the archive after December 1875.

One line remains in court documents:

“Charges dropped. Disposition unknown.”

The Meaning of the Case

The lesson of the Morrison case is not that justice prevailed.

It did not.

Nor that truth triumphed.

It did not.

The lesson is that even when the machinery of a racialized legal system is operating at full force, even when power structures align to erase a single life, testimony—fragile, insufficient, dangerous—can occasionally slow that machinery just long enough for one child to step off the gallows.

Eli lived.

And sometimes, in the face of systemic injustice, survival itself is the closest thing to justice the world will allow.

News

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was Heartbr | HO!!

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was…

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She | HO!!

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She |…

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!!

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!! They…

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club & Sees | HO!!

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club &…

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was.. | HO!!

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was…..

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her. Why? | HO!!

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her….

End of content

No more pages to load