Boy Poses with His Mom in 1933 — What Appears in His Eyes When Zoomed In Is Chilling | HO!!

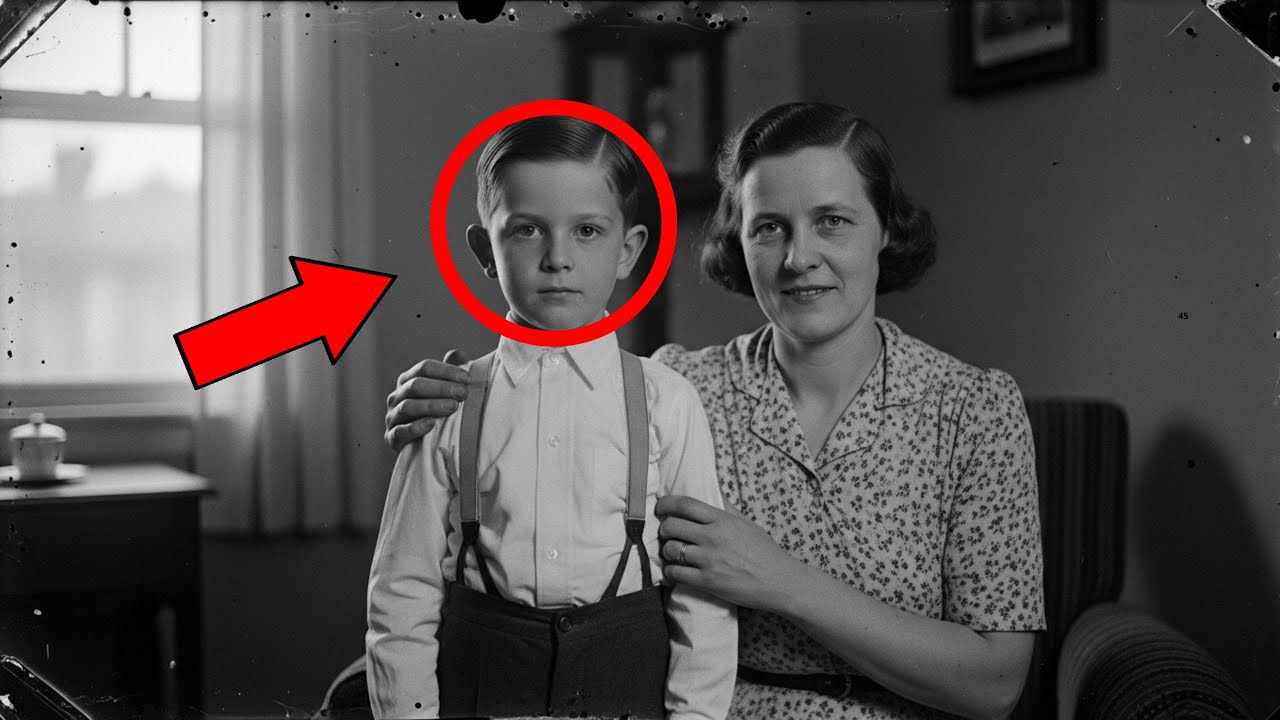

A dusty Depression‑era family portrait—an eight‑year‑old boy beside his widowed mother in autumn 1933—looked ordinary until a forensic photograph analyst enlarged the child’s pupils.

What appeared there, according to the reconstruction, was not the expected diffuse glare of an outdoor snapshot, but the reflected outline of a figure standing behind the camera in a menacing pose. That microscopic glint would become the alleged key that unlocked a pattern of forgotten child disappearances spanning multiple New England towns—and later, if the narrative holds, several states.

The discovery in the attic

Dr. Elena Vasquez, described as a specialist in early 20th‑century photographic processes, was combing through estate boxes in a decaying Salem, Massachusetts, Victorian home following the death of its nonagenarian owner, Millicent Thornbury. The attic held the usual domestic chronicle—birthdays, seaside outings, holiday tables.

Then one 1933 print stopped her: mother in wool coat and cloche hat; son in knickers, suspenders, neatly parted hair. Their poses were composed; their expressions were not synchronized. The boy’s smile read as stiff theater. His eyes, under magnification, seemed to contradict his mouth.

What the eyes allegedly showed

Using a high‑power loupe and controlled illumination, Vasquez examined the emulsion. Reflected in the boy’s pupils, she later recounted, was a dark‑clad figure directly behind the photographer’s position, arms raised as though holding an object above shoulder level.

The boy’s pupils, though tiny, appeared to encode tension—dilated edges, micro‑creases at the inner canthi, and a directional gaze inconsistent with relaxed portraiture. The mother’s posture showed no corresponding alarm. That asymmetry suggested, to the investigator, an off‑frame threat perceived by the child but either unseen or unregistered by the adult.

Linking the faces to names

Estate documents identified the subjects: Jonathan Thornbury, age eight; his mother, Katherine, a widowed seamstress navigating the economic freefall of the Great Depression. Archival family papers included a brittle 1933 police report: Jonathan vanished that November—no witnesses, no ransom, no physical trace.

Letters Katherine wrote to Boston relatives in the preceding weeks chronicled behavioral changes: fear of going outside, drawings of a “dark man,” refusal to be photographed. A final letter mentioned a Dr. Morrison and an upcoming consultation about Jonathan’s “imagination.”

Convergence on a dual professional

A stamp on the photograph’s reverse read: H. Morrison Photography Studio. Local historical society index cards listed a Harold (or Henry) Morrison operating a combined photography studio and medical practice from 1930–1934—an unusual Depression‑era dual livelihood but not implausible.

Clippings from early 1934 referenced parental complaints about a physician’s “unnecessary photographic documentation” of children. By late November 1933—the month of Jonathan’s disappearance—Morrison’s studio and practice closed abruptly. Municipal exit records noted a purported relocation “for health,” without forwarding detail.

Broadening the scope: missing children pattern

Vasquez’s file dive, as reconstructed, expanded beyond Salem. Police ledgers, newspaper morgues, and fragmentary community notices revealed at least seven disappearances of children aged six to ten between 1931 and 1934 within roughly fifty miles: Marblehead, Beverly, Gloucester, others.

Common elements allegedly surfaced: economically strained households; recent interactions with a traveling or unusually accommodating doctor or photographer; child reports (often dismissed) of a “picture man.” In multiple instances, siblings recalled fear attached specifically to cameras or medical visits.

The basement search

Armed with pattern summaries, Vasquez approached modern Salem detectives. A current owner allowed access to the former Morrison studio building, now apartments. Ground‑penetrating scanning in a basement zone identified a density anomaly behind inconsistent brickwork.

Removal of the newer wall section revealed a sealed chamber: 1930s darkroom equipment, chemical canisters, lighting rigs, storage crates—and, most disturbingly, hundreds of child photographs.

According to the narrative, many images showed escalating distress; some subjects matched archival missing‑person descriptions. Among them: a sequence featuring Jonathan, culminating in a frame mirroring the reflected tableau in his pupils—Morrison, rope raised behind the camera apparatus.

The journal

Investigators reportedly recovered a bound notebook in precise medical handwriting. Entries from 1930–1933 outlined selection criteria: families strained by economic hardship, parents working long hours, socially isolated households. Phrases allegedly emphasized ocular cues: “Eyes disclose pliability… capacity for silence.”

One passage describing Jonathan referenced “final portrait session” and “awareness without flight.” An abrupt termination entry in November 1933 noted “attention growing” and the need to “relocate operations.”

Interstate drift

Subsequent research, the account claims, found a physician-photographer adopting derivative names in California’s Central Valley by 1934, offering low‑cost services to Dust Bowl migrants. A string of migrant child disappearances previously attributed to transience reportedly exhibited analogous pre‑loss photography encounters.

A later confrontation narrative in 1938 placed the suspect fleeing amid a desert storm; no confirmed recovery followed. Additional caches of photographs allegedly surfaced on rented farmland, extending the temporal scope of victimization.

Forensic methodology (as portrayed)

Modern enhancement tools—high‑resolution scanning, contrast layer isolation, micro‑reflection modeling—were credited with extracting actionable detail from the 1933 print. Analysts simulated environmental light vectors to test whether artifact glare, retouching, or emulsion defects could mimic the reflected figure; alternative hypotheses were reportedly discounted.

Chain‑of‑custody reconstruction for the original print became essential to arguing evidentiary integrity across nine decades of storage, inheritance, and environmental exposure.

Systemic context

The Depression strained local policing bandwidth; missing child cases without immediate ransom dynamics often received minimal sustained attention. Cross‑jurisdictional data sharing was fragmentary; a predatory actor exploiting medical authority and photography—symbols of progress and trust—could, in this depiction, operate within systemic blind spots.

The case study (fictional or otherwise) underscores vulnerabilities: deference to professional status; dismissal of children’s diffuse fear narratives; absence of centralized pattern recognition.

Ethical and interpretive caution

While the narrative dramatizes a revelatory pupil reflection, real‑world application of forensic photogrammetry to micro‑reflections carries significant limitations: curvature distortion, resolution thresholds of period lenses, grain structure, and risk of pareidolia (perceiving engineered meaning in ambiguous visuals).

An investigative framework demands independent replication, blind analysis, and transparent exclusion of artifact pathways before elevating an image detail to evidentiary pivot.

Alleged impact and legacy

According to the account, the rediscovered photograph catalyzed cold case reviews, genealogical outreach, and procedural reforms in historical evidence screening. A foundation named for the child was said to train professionals to interpret subtle distress signals and prioritize children’s expressed fears despite absent corroborative adult perception.

Takeaways

Even read as a constructed scenario, the story illustrates:

Latent data can reside in mundane artifacts (family prints).

Socioeconomic crises create exploitation vectors for credentialed predators.

Children’s qualitative fear reports may precede pattern recognition in official systems.

Forensic optimism must be balanced against methodological rigor to avoid misattributing ambiguous micro‑visual phenomena.

Conclusion

A static portrait—mother steady, child constrained—becomes, in this investigative retelling, a compressed archive of unnoticed warning. Whether literal history or cautionary narrative architecture, the piece reminds practitioners that evidence sometimes hides at scales dismissed for generations, and that vigilance must extend both to technological opportunity and to the interpretive discipline required to wield it responsibly.

News

Mom Installed a Camera To Discover Why Babysitters Keep Quitting But What She Broke Her Heart | HO!!

Mom Installed a Camera To Discover Why Babysitters Keep Quitting But What She Broke Her Heart | HO!! Jennifer was…

Delivery Guy Brought Pizza To A Girl, Soon After, Her B0dy Was Found. | HO!!

Delivery Guy Brought Pizza To A Girl, Soon After, Her B0dy Was Found. | HO!! Kora leaned back, the cafeteria…

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!!

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!! While Charlene was…

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!!

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!! The prosecutor…

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!!

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!! Thursday, October…

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!!

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!! Mr. Andrews pulled out a folder like he’d been waiting…

End of content

No more pages to load