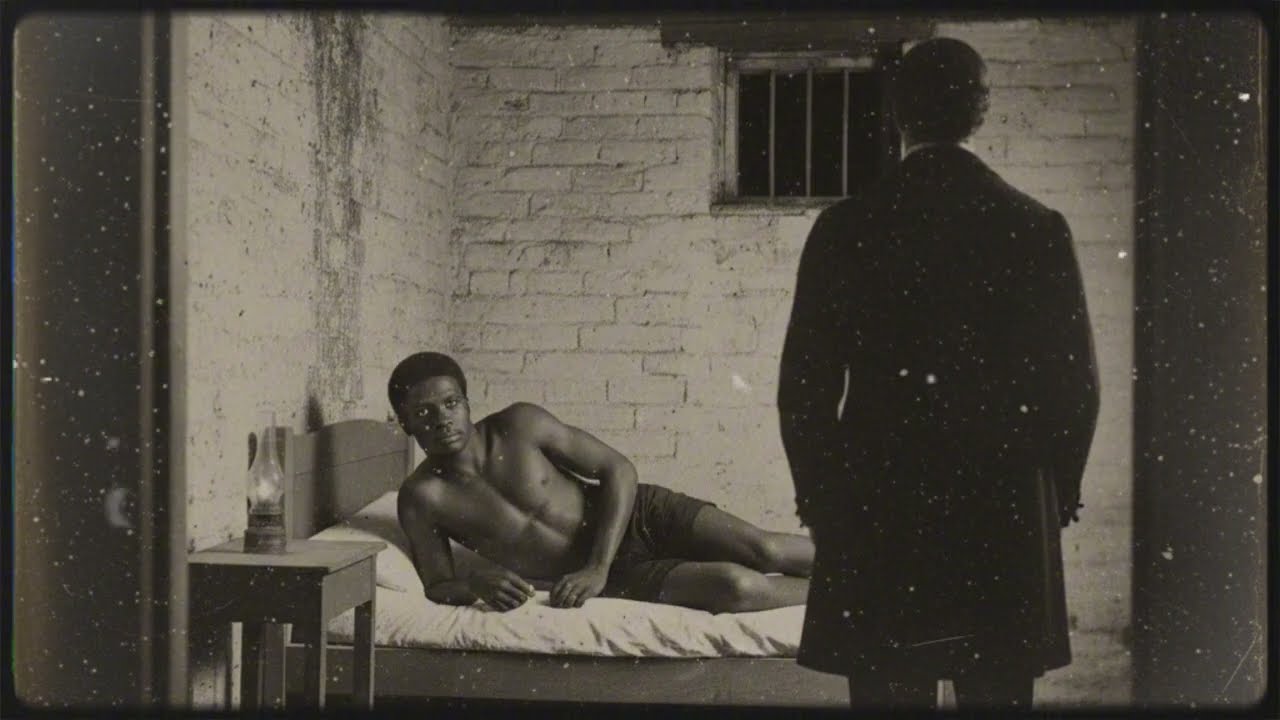

(Charleston, 1843) He Was Sold to the Rich Every Night — Until He Made Them Pay in Blood | HO

Part I — The Cellar No One Talked About

Charleston, South Carolina, has always been a city that knows how to bury its dead—and its secrets. The pastel facades, cobblestone streets, and clipped gardens tell one story: wealth, refinement, and lineage so old that even the magnolias seem to bow to it. But beneath that elegance lies another Charleston, a city built on bondage, exploitation, and the careful orchestration of silence.

In October 1843, that silence cracked.

Twelve of Charleston’s most respected citizens—seven women, five men, each from families whose names still appear in dusty society ledgers—entered a cellar beneath Thornfield Manor for a private gathering. They emerged at dawn, barely able to walk, some in shock, some incoherent, all refusing to speak.

The house servants who peeked into the cellar afterward swore they found overturned chairs, fractured iron rings, spilled tinctures, and a scattering of scorched wooden tools. But they found no culprit.

The young enslaved man at the center of the incident—an 18-year-old with striking blue eyes named Josiah—had vanished into the night.

No one reported the crime. No magistrate was informed. No doctor summoned. Charleston closed over the event like water over a stone.

But fragments of the story remain—hidden in family letters, court petitions with names blacked out, and whispered recollections recorded decades later. When pieced together, they reveal a truth so unsettling that even now, nearly two centuries later, Charleston’s oldest families would rather the cellar of Thornfield Manor remain undisturbed.

This is that truth.

A House Built on Elegance—and Rot

To understand the night of October 16th, 1843, investigators must start with the couple who orchestrated the gathering: Silas and Vivien Whitmore.

Thornfield Manor—once regarded as one of the finest rice estates along the Ashley River—was more than a plantation. It was a stage, and the Whitmores played their parts beautifully. In public, Silas was the archetypal gentleman-planter: charitable, well-mannered, meticulously respectable. Vivien was the consummate hostess: elegant, poised, and trained since childhood to smile as though her life depended on it.

Because it did.

Born Vivien Adelaide Bowmont in 1812, she belonged to a family so entrenched in Charleston aristocracy that her lineage appeared in society directories before the nation itself did. Her father, Edmund Bowmont, owned over 200 enslaved people and believed daughters were ornamental liabilities until they were married off. Vivien’s childhood, sewn with lace, was stitched together with trauma: beatings in the yard, women dragged by the wrist into bedrooms, and the quiet complicity of plantation wives who had learned that endurance was the only virtue society rewarded.

Silas Whitmore had demons of his own—private ones, shameful ones, shaped by a rigid upbringing and desires he could not openly name in a society that punished deviation with ruin. His lifelong struggle carved him into a man capable of compartmentalizing everything: want, guilt, cruelty, and the lives around him.

The Whitmore marriage was cold from the start—an economic pairing masquerading as domestic union. They grew to resent each other with a precision so practiced it became indistinguishable from routine.

But the story truly begins the day Vivien saw Josiah.

The Boy with Blue Eyes

Josiah was born on Thornfield’s soil, the son of an enslaved woman named Dinah and, according to every whispered rumor that persisted through the quarters, the overseer who despised him. His pale blue eyes—an inheritance forced upon him—marked him as different from birth, both in appearance and in the resentment he evoked.

As a child he was quiet, stuttering, and sickly. He spent most of his early years pushed aside: too light for field work, too unsettling for house service, too visibly out of place in any role Charleston had scripted for the enslaved. He grew up with the kind of loneliness that hollows a person from the inside.

Then, at around fifteen, everything changed.

Illness fled. His body sharpened and lengthened. The awkward boy transformed into a striking young man—tall, muscular, and beautiful in a way that unsettled everyone who looked at him. Even those who avoided acknowledging the enslaved beyond their labor found themselves murmuring about “the blue-eyed boy on Whitmore land.”

He drew attention he never asked for. Never wanted. Never understood.

And in 1841, he caught Vivien Whitmore’s gaze.

The Quiet Beginning of a System

No official records exist documenting what began afterward. But scattered recollections from servants, diary fragments, and unsigned letters discovered decades later point to a pattern: something transpired that summer that awakened a hunger in Vivien—a hunger for power, sensation, and control in a life suffocated by restraint.

Silas, discovering what Vivien had initiated, didn’t react with outrage. He reacted with opportunity. What she had begun for escape, he repurposed for profit.

By late 1841, something systematic had formed—something organized, secretive, and lucrative. Wealthy acquaintances of the Whitmores began arriving quietly at unusual hours. The cellar beneath the manor—once used for storage—became something else entirely: a private chamber where men and women could engage in acts forbidden in public yet protected by status and silence.

Josiah, at sixteen, became the centerpiece.

Enslaved people had no legal protections. Consent was irrelevant. Their bodies were commodities, to be used however their owners or renters demanded. This was the unspoken truth of the slave economy—a truth students never read in textbooks, a truth Charleston whispered about only behind closed doors.

For two years, Josiah was sent into that cellar night after night. Sometimes three nights a week, sometimes six. The clientele grew. The profits soared. Silas oversaw the business with the clinical detachment of a banker managing ledgers; Vivien managed the clientele with the grace of a socialite arranging soirées.

Josiah was not a person in that space. He was an attraction, a curated experience, a living commodity.

But he was also observing.

And learning.

A Mind on the Edge

Survival inside Thornfield’s cellar required dissociation—a skill many enslaved people learned to protect themselves when the world became unbearable. Josiah grew adept at slipping out of himself, hovering somewhere above the terror and humiliation, watching from a safe distance.

But the human mind is not infinitely elastic. At some point, it snaps.

For Josiah, that moment came in March 1843.

A scheduling error—one of the rare cracks in the Whitmores’ system—placed two clients in the cellar at the same time. What unfolded that night pushed Josiah beyond the limits of endurance. When Vivien checked on him the next morning, she found him curled on the floor, eyes open but vacant, breathing but unresponsive.

A doctor—bribed to silence—called it shock. He warned that continuing to force him into the cellar could cause permanent psychological damage.

The Whitmores gave him three days of rest.

Then the schedule resumed.

Except Josiah had changed.

His expression flattened. His stutter disappeared. He moved with a calm that unnerved even the Whitmores. His eyes no longer pleaded or protested—they merely watched.

Viven believed he had finally submitted.

Silas believed he had become numb.

Both were wrong.

Josiah had not broken. He had begun to plan.

The Slow Conspiracy

In the months that followed, Josiah cultivated a mask of obedience so flawless that even Thornfield’s seasoned enslaved population couldn’t detect anything beneath it. But behind that mask was a mind quietly collecting information:

clients’ names

their vulnerabilities

their fears

their shame

their reliance on secrecy

their eagerness to believe he had accepted his fate

He learned the schedule from the inside. He memorized the layout of the cellar, every bolt and hinge. He studied tinctures and plants from the plantation gardens—materials capable of inducing paralysis, hallucinations, or respiratory distress.

What he built was not a plan for escape.

It was a plan for reckoning.

An Invitation They Couldn’t Refuse

In late September 1843, Vivien proposed a profitable idea: a special event, a night where all twelve regular participants would attend together. A gathering disguised as a genteel weekend social event, with a darker purpose unfolding after midnight.

Twelve guests.

Twelve exploiters.

Twelve people who believed themselves untouchable.

Attendance cost $1,000 per person.

Silas approved immediately.

Josiah said nothing.

But when Vivien asked if he understood what would be expected of him on that night, he looked up with those pale, depthless eyes and replied:

“Whatever you wish, mistress.”

Vivien smiled. She believed she had finally shaped him into the perfect instrument of profit.

In reality, she had given him the perfect staging ground.

The Cellar Prepared

Thornfield’s staff later reported that Josiah volunteered—volunteered—to help prepare the cellar for the event. That alone should have alarmed the Whitmores. But arrogance is a powerful blinder.

For two weeks, Josiah arranged chairs, adjusted lighting, cleaned lanterns, and brought in fresh linens. Silas praised his diligence. Vivien complimented his obedience.

Neither noticed that he subtly replaced hardware, altered chains, and repositioned keys.

Nor did they notice when he prepared a drink—“a special tincture to enhance the experience”—that he presented to Vivien for approval.

She tasted it. Declared it perfect.

She didn’t taste the other components he had added—measured with precision, designed not to kill but to control.

The trap was ready.

And on the night of October 16th, Charleston’s elite walked straight into it.

Part II — The Night Charleston Tried to Forget

When the twelve guests arrived at Thornfield Manor on the evening of October 16th, 1843, nothing about the gathering suggested the infamy it would one day hold. The Whitmores hosted social events frequently, and the city’s upper circles were accustomed to Thornfield’s candlelit dinners, music spilling into the veranda, and conversations that danced skillfully around the darker truths of plantation life.

This night was different. Yet no one recognized it—not yet.

Vivien greeted her guests with the polished warmth expected of a Charleston hostess. Silas played the attentive gentleman, engaging the men in polite conversation about crops and tariffs while the women drifted through the drawing room in satin and silk.

Nobody suspected that the enslaved boy who served their wine had spent the past two years studying each of them with painstaking attention.

Nobody recognized the stillness behind his smile.

Nobody noticed the quiet anticipation in his breath.

Nobody saw the storm coming.

A Toast Before Descent

At precisely 11:30 p.m., Silas ushered his twelve invited guests into the drawing room for what the invitations had described only as “a private experience.” Servants were dismissed to their quarters. The remaining household staff—those essential to the night’s secret—were confined to the rear wing under threat of punishment.

The drawing room doors closed.

Silas poured twelve small glasses of an amber-colored tonic.

“An aperitif,” he announced. “A gift from Josiah. Something to heighten sensation and relax the nerves.”

Several guests laughed softly. Others flushed with expectation. They believed they were about to indulge in a novelty—a shared sin, a forbidden pleasure hidden neatly behind Charleston’s carefully curated respectability.

No one questioned the drink.

No one asked about ingredients.

No one imagined it was the final voluntary act they would perform that night.

Josiah stood in the doorway holding a tray. He moved gracefully from guest to guest, offering each glass with a soft smile. Some murmured thanks. Some held his gaze longer than propriety allowed. Others avoided his eyes entirely, unable to reconcile the truth of their own behavior with the fiction they had constructed around it.

For one fleeting moment, he looked at Vivien Whitmore.

She interpreted the look as obedience.

Silas interpreted it as trained submission.

Both were wrong.

Descent Into the Cellar

At midnight, the Whitmores guided their guests down the narrow stairwell leading to the cellar. It was not the first time most had descended these steps, though never before in a group. On prior nights, they had arrived alone, cloaked in secrecy, driven by desire or cruelty or boredom or simply the intoxication of owning what was not theirs to take.

But tonight, they descended together, a procession of Charleston’s most esteemed citizens walking willingly toward a reckoning none could have imagined.

The moment they reached the final step, a ripple of confusion spread through the group.

The cellar did not look the way they remembered it.

Gone was the single cot in the center of the room. Gone were the arrangements designed to isolate the night’s “entertainment.” Instead, twelve high-backed chairs were placed in a circle, arranged like an audience facing the center.

And in that center stood Josiah.

Unchained.

Unbound.

Waiting.

At first, no one spoke. Then Silas’s voice broke through the quiet, but it sounded strained, slurred at the edges.

“What… what is the meaning of this?”

He tried to step forward, but his leg buckled. He gripped the wall.

One by one, the guests felt the same sensation—the creeping heaviness in their limbs, the inability to fully control their hands, the sudden instability in their steps.

Panic flickered.

“What’s happening?” hissed Cordelia Ashworth, clutching the banister as she slid into the nearest chair.

“My fingers—” gasped Theodore, staring at his unresponsive hands.

“It’s the drink,” whispered Helena, voice trembling as she sank weakly into her seat. “It’s—something’s in the drink.”

Only Josiah’s voice was steady.

“It won’t stop your breathing,” he said. “It won’t stop your heart. You are fully conscious. You can hear me. You can see me. You can think. You simply cannot stand.”

No one had ever heard him speak like this—clear, calm, without a hint of the old stutter.

Silas slumped into a chair, jaw clenched in dawning horror.

Vivien, breath ragged, managed to choke out, “Josiah… what have you done?”

He walked toward her, footsteps slow, measured.

“Exactly what you taught me,” he replied.

“Tonight, You Are the Ones Who Sit and Endure.”

When all twelve were seated—some shivering, some staring wildly, some fighting the paralysis inch by inch—Josiah moved to the center of the circle.

He waited. Allowed them to feel the full weight of their helplessness. Allowed them to realize that the power they once wielded had been stripped away entirely.

Then he began.

“For two years,” he said quietly, “I was brought into this room. Sometimes three nights a week. Sometimes six. Not because I chose it. Not because I agreed. Because I had no rights. No voice. No recourse.”

Vivien flinched.

Helena shut her eyes tightly.

“But tonight,” he continued, “you will listen.”

He stepped toward the first chair—Helena, the banker’s wife, who had always masked her participation behind soft words and self-deception.

“You told yourself you weren’t hurting me,” he said. “You said it didn’t count because I was enslaved. You convinced yourself the things you did were harmless indulgences. You needed to believe that to sleep at night.”

Her lips trembled, but no sound emerged. The paralysis held her silent.

“You were wrong,” he whispered. “And you knew it.”

He moved to Theodore next—a judge known for his severity and cruelty, a man who had built an entire career on punishing others.

“You liked fear,” Josiah said, voice still calm. “You liked power. You liked that I could not say no. You told yourself that made you dominant. That it made you a man.”

Theodore stared forward, eyes wide, haunted.

“Tonight,” Josiah added, “look at what a man you are.”

He turned to Cordelia Ashworth—the one whose fascination had started everything.

“You called that night an adventure,” he said. “But I was sixteen years old. You were old enough to know the difference between desire and violation. You told yourself I was lucky. That you were doing me a kindness by choosing me.”

Cordelia shook uncontrollably.

Josiah’s voice remained level.

“You paid for access to a boy who begged you to stop. Call it what it is.”

Silas groaned, fighting the paralysis with fury instead of fear.

“Enough,” he tried to spit, but the words were thick. “You have no idea—”

Josiah turned to him last.

“You could have protected me,” he said. “You could have refused to allow any of this. Instead, you turned me into profit.”

Silas’s eyes filled with a mixture of shame and hatred—directed not at himself, but at the boy he had horrifically underestimated.

“You sold me,” Josiah said quietly. “Not just my labor. My body. My dignity. My life.”

Then he faced Vivien.

“You told yourself this was business,” he said. “That I was property. That the fear you saw in my eyes didn’t matter.”

Vivien’s breath hitched in her throat.

“And you learned to enjoy it.”

Her face crumpled.

But Josiah did not raise his voice. He didn’t need to. His control was absolute, and every word landed like a blade sharpened by truth.

Psychological Ruin

For eight hours, the cellar of Thornfield Manor became a courtroom with no judge, no jury, no appeal.

But Josiah wasn’t inflicting physical violence. He didn’t strike them. Didn’t touch them. Didn’t harm them in any concrete way.

Instead, he dismantled them—one by one—with the only weapon they had never expected him to wield:

the truth of their own actions.

He confronted them with the hypocrisy of their piety, the viciousness behind their gentility, the moral rot beneath their polished reputations. He recited their words back to them—their excuses, their justifications, their lies. He forced them to sit with everything they had spent two years denying.

Some sobbed into their collars.

Some trembled uncontrollably.

Some stared ahead, hollow, shattered.

The drug allowed tears but denied movement. Every emotion was trapped inside their bodies, magnified by helplessness, intensified by the impossibility of looking away.

And the more they broke, the calmer Josiah became.

For the first time in his life, he was not powerless.

Dawn

As light seeped into the cellar from the small window high on the wall, the paralysis began to fade. Fingers twitched. Arms moved. A few collapsed onto the stone floor, bodies convulsing with sobs.

Josiah stood in the center, watching them regain movement.

“You can leave,” he said simply.

Nobody moved.

“I’m not stopping you.”

Still, no one rose.

Finally, he added the only threat he ever voiced:

“If any of you speak of this night—

I have written everything you did.

Every name.

Every detail.

Those letters will be sent if anything happens to me.”

The implication was clear.

Expose him, and they expose themselves.

Destroy him, and they destroy themselves.

The power they once abused now belonged entirely to him.

He walked up the stairs without looking back.

Behind him, twelve of Charleston’s most powerful citizens remained frozen—no longer because of the drug, but because they had seen themselves clearly for the first time in their lives.

And they could not bear the sight.

Part III — The Vanishing, the Cover-Up, and the Truth History Tried to Bury

When Josiah Freeman walked out of the cellar at dawn on October 17th, 1843, he did not run. He did not hide. He did not look over his shoulder. According to the only surviving account—a whispered recollection from a house servant more than sixty years later—he walked across the yard as calmly as if he were heading to the fields for another day of labor.

But he never returned.

By noon, the Whitmore household was in chaos. Servants reported seeing their mistress vomiting in the rose garden. Silas locked himself in his study, emerging only to demand whiskey. The twelve guests dispersed with an urgency bordering on madness—faces pale, limbs trembling, avoiding eye contact with everyone.

No one dared ask questions.

No one dared speak the truth.

And no one dared admit what had happened in that cellar.

It would take less than a week for the consequences to begin.

The Aftermath No One Could Explain

Charleston society noticed immediately—but misunderstood everything. Gossips said Helena Caldwell had fallen ill. That her nerves had collapsed from “women’s troubles.” Closer acquaintances whispered that she had taken to locking herself in her bedroom and weeping without explanation.

They did not know she had stopped attending church because she could not bear to hear the word redemption without seeing Josiah’s eyes staring back at her.

Judge Theodore Barrow began drinking heavily. In the weeks that followed, he appeared in court only once—stumbling, disheveled, barely able to speak. He claimed exhaustion. His colleagues suspected stress.

No one guessed the truth: that he awoke every night drenched in sweat, convinced he was back in that cellar, hearing his own words hurled at him with devastating clarity.

Cordelia Ashworth withdrew from society entirely. When friends called on her, they were told she suffered migraines. Those who saw her described a woman who could not look in mirrors, who flinched at shadows, who seemed to shrink from touch as though the air itself accused her.

Others unraveled even more violently.

One married woman was discovered in her dressing room with blood on her gown and a knife on the floor. She had not attempted suicide. Instead, she had cut out her own tongue.

When her horrified husband demanded an explanation, she wrote one sentence with shaking hands:

“So it can never speak what I have done.”

Within two months, two of the male participants were dead by their own hand.

One filled his coat pockets with stones and walked deliberately into the Combahee River. Another shot himself in his study, leaving behind a single line:

“I see his eyes everywhere.”

The Whitmores, curiously, survived physically.

But their marriage died.

They could not stand to be in the same room. They avoided each other as though proximity alone would resurrect the night they had tried to bury. Vivian drank quietly, relentlessly. Silas drank loudly, destructively. By Christmas 1843, they were living on opposite sides of the manor.

Servants described the house as “a tomb where the living paced like ghosts.”

Charleston’s Quiet Conspiracy

One might ask: why did no one uncover the truth then? Why did twelve people unravel publicly without raising suspicion? Why did no magistrate investigate?

The answer is simple.

Because every person in that cellar had something far more valuable than innocence.

They had reputations to protect.

Charleston in the 1840s was a place where status outweighed morality, where image eclipsed truth, where families guarded their names with a ferocity that justified any amount of deceit.

If twelve prominent citizens admitted what had happened—

what they had done—

what they had paid for—

they would not only destroy themselves, but their families, their estates, their social circles, their legacies.

Silence was the only currency left to them.

And the Whitmores paid it.

So did their guests.

The cover-up was not orchestrated. It did not require meetings, agreements, or threats. It was instinctive—an unspoken pact forged by shame, fear, and self-preservation.

No one spoke.

No one wrote.

No one remembered—at least not publicly.

And in that silence, Josiah disappeared.

December 15th, 1843: The Day the Whitmores Finally Broke

Two months after the cellar incident, Josiah’s absence became impossible to ignore. Silas Whitmore rode to Charleston to post a runaway notice—thinly veiled, carefully worded, avoiding any detail that would raise questions.

But servants noticed something peculiar.

Silas seemed relieved when he tacked the notice to the courthouse board. Almost eager to leave it behind. As if hoping that by putting Josiah’s name on paper, he could expel the boy from his mind.

Vivien, for her part, spent nights standing at her window, staring into the fields as though expecting Josiah to return—not to harm her, but to finish the psychological destruction he had begun.

He never returned.

Or perhaps he didn’t need to.

Because everything she feared—every memory, every word he had spoken—was already inside her.

The Escape

In the winter of 1843, as the Whitmores dissolved, as Charleston whispered behind closed doors, as the twelve participants fell apart in different ways—

Josiah was walking north.

He followed the river first, then the stars, then a group of enslaved people making a dangerous run toward freedom. He said little, but they later recounted (in testimonies preserved by abolitionist societies) that he seemed both broken and unbreakable.

He rarely slept.

He never wept.

And whenever he crossed frozen streams or crept past lantern-lit patrols, he walked with a stillness that frightened even the others fleeing with him.

He did not speak of Charleston.

He did not speak of the cellar.

He never said his name.

Philadelphia: Rebirth Under Another Name

On January 28th, 1844, surrounded by abolitionists and Quakers, the blue-eyed man who had walked through hell introduced himself for the first time in his life.

“Josiah Freeman,” he said.

The choice was deliberate.

Sharp.

Defiant.

The name of a man, not property.

The name of someone who had survived the unspeakable.

The name of someone determined never to belong to another human being again.

Philadelphia abolitionists described him as:

reserved

disciplined

unshakably calm

fiercely protective of the vulnerable

He never sought pity. Never raised his voice. Never discussed his past—except to say that slavery produced horrors that polite society refused to acknowledge.

But he did something extraordinary.

He began helping others escape.

For a man whose trauma centered on being used, controlled, and dehumanized, dedicating his life to freeing others was an act of breathtaking resilience.

By 1850, he had guided at least 47 people through the Underground Railroad.

By 1860, over 100.

When the Civil War erupted, he used his knowledge of South Carolina terrain to guide Union scouts. His expertise saved lives.

The government never rewarded him formally. But those he helped remembered him. Many of their descendants still speak of a tall man with pale eyes who appeared out of nowhere in the dead of night and led their ancestors to freedom.

He died in 1888, in a small Philadelphia house filled with the families he had helped save.

His last words, according to local records:

“I’m free. Finally free.”

A simple sentence.

But everything he never said was contained inside it.

The Fate of Thornfield Manor

Thornfield did not outlive the Civil War.

By 1863, the enslaved population—long oppressed, long brutalized—burned it to the ground during a wave of uprisings that swept through Lowcountry plantations. The Whitmore family fled. The land was abandoned. Silas disappeared from records soon after. Vivien died in obscurity.

The cellar was reduced to foundations and ash.

But stories survive ashes.

What History Erased

The real tragedy is not that Josiah inflicted a night of psychological reckoning on the people who had exploited him.

The tragedy is that his story could have been one of thousands.

Slavery was not only forced labor. It was forced intimacy, forced obedience, forced silence. Sexual exploitation was not an aberration—it was an industry. A commodity. A weapon.

Enslaved women were violated so routinely that planters joked about “breeding.”

Enslaved men were assaulted, humiliated, emasculated, or coerced in ways history books still refuse to describe.

And when survivors fought back—physically, psychologically, or simply by escaping—they were branded as violent, dangerous, monstrous.

Josiah was none of those things.

He was a boy born into a world that despised him, used him, and discarded him.

And yet he survived.

He reclaimed himself.

He reclaimed others.

His story is fiction—but the system that produced it was real. Painfully real. Brutally real. Quietly real.

What he endured reflects what thousands endured in silence.

What he did in that cellar reflects a truth America rarely confronts:

You cannot exploit human beings without destroying some part of yourself.

Every participant in Thornfield’s secret nights believed they were untouchable.

Josiah proved otherwise.

The Final Reckoning

So what do we make of him today?

Was Josiah a villain?

A vigilante?

A revolutionary?

A survivor shaped by unimaginable harm?

Perhaps he was all of these.

But the question historians and ethicists should be asking is not:

“Was he justified?”

The question is:

“What creates a person with nothing left to lose?”

Because once created, such a person does not break.

They reshape the world around them.

Charleston, 1843: The Story the City Still Won’t Claim

Nearly two centuries later, Charleston remains a place where history is curated, softened, and sanded at the edges. Tour guides rarely speak of sexual violence on plantations. Museums mention it in footnotes. Textbooks bury it under statistics.

But the cellar at Thornfield forces us to look.

Not at Josiah.

But at the people who created him.

The genteel.

The refined.

The respectable.

The ancestors whose portraits still hang in Charleston parlors.

Their descendants prefer silence.

Just like they always did.

Why This Story Matters Now

Because the violence of enslavement did not end in 1865.

Its echoes still shape families, communities, and institutions.

Its legacy still lives in trauma passed down quietly through generations.

Josiah’s fictionalized account is believable not because it is sensational—but because it mirrors the suppressed truth of a system built on domination and denial.

He did not seek vengeance.

He sought acknowledgment.

He forced his abusers to face the truth they spent their lives avoiding.

That was his rebellion.

That was his freedom.

Epilogue — Survival Is the Greatest Revenge

The cellar is gone.

The Whitmores are gone.

Charleston has paved over its secrets.

But somewhere in the archives of abolitionist societies in Philadelphia, there remains a sketch of a tall man with striking blue eyes and a quiet expression.

Beside it is a short note:

“A survivor. A guide. A man who saved many.”

He lived.

He fought back.

He freed others.

And sometimes, that is the only justice history allows.

News

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!!

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!! So he hires a French…

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE IT? | HO!!

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE…

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!…

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal | HO!!

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal…

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. | HO!!

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. |…

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender | HO

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender |…

End of content

No more pages to load