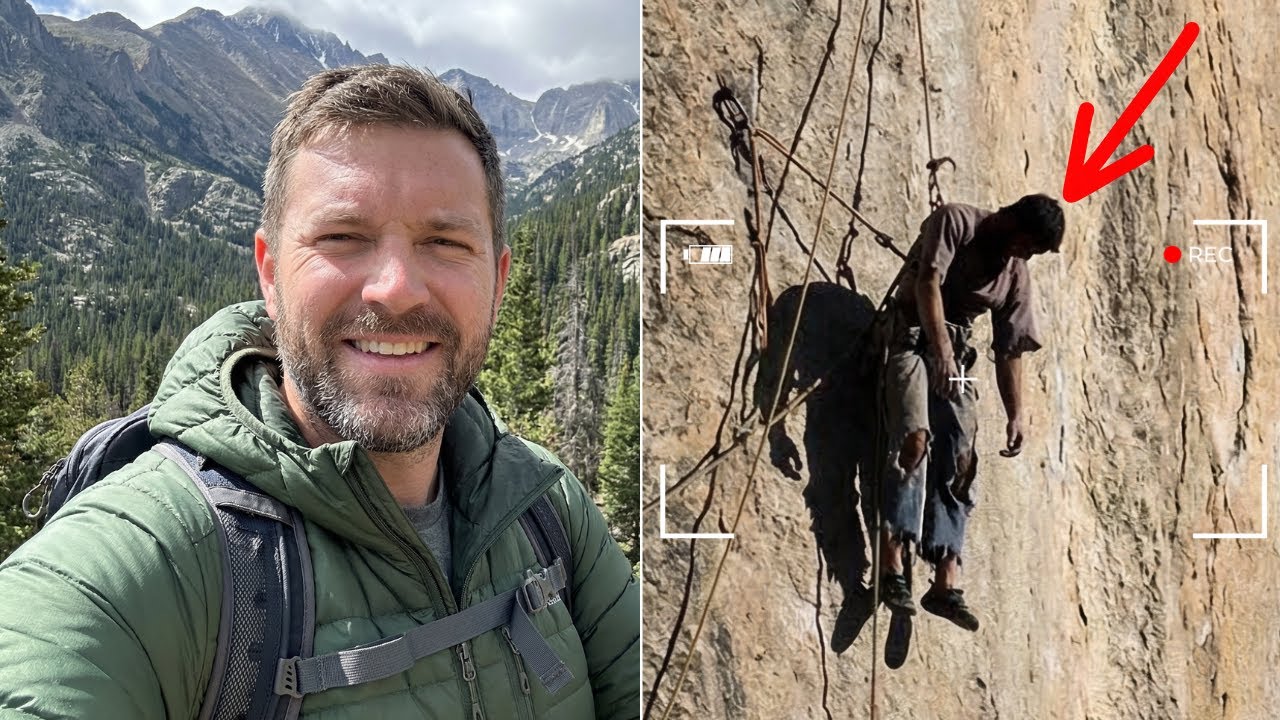

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO”

A promise feels strongest right before it becomes the thing you chase.

Before sunrise the next morning, Patricia saw Derek’s truck pull out of the gravel lot just after 5 a.m. The sky was still dark. Frost covered the glass like a second skin. He drove north on Highway 62 toward the access road leading to the base of Mount Silverton. Later, his white Ford Ranger with Boulder County plates was found parked at the trailhead—locked, undisturbed, as if it had been left with intention.

Inside, investigators discovered a handwritten note on the dashboard: planned route, estimated timeline, and Jennifer’s contact information. A quiet precaution—an experienced climber’s way of acknowledging risk without staring at it.

Derek began his approach hike around 6:30 a.m. The trail to the north face was steep and rocky, winding through dense pine before opening onto a boulder field stretching toward lower cliffs. According to his itinerary, he planned to reach a base campsite by early afternoon, rest, and begin technical climbing the next day.

The weather was exactly as predicted: cold, clear, light wind. For the first day, everything fit the plan.

Then came silence.

No message on the 12th. None on the 13th. By the evening of March 14, Jennifer’s worry turned into something sharp enough to cut. She tried calling his phone—no signal in the backcountry. She logged into their satellite messenger account—no new updates. She stared at the screen the way you stare at a door that should open any second.

On the morning of March 15, she called the Granite Falls Sheriff’s Department and filed a missing person report. Deputy Leonard Cross took the call. He spoke in the careful tone of a man trying to be honest without being cruel.

“Ma’am,” he said, “he’s experienced. It’s not uncommon to lose communication out there.”

“He told me he’d check in,” Jennifer said, and her voice betrayed her. “He always checks in.”

Cross paused, then answered in a way that told her he’d made a decision. “I’ll send a ranger to the trailhead.”

By noon, the ranger confirmed Derek’s truck was still there. No one had seen him return. Sheriff Raymond Baxter, twenty-five years in the department, knew the north face well enough to respect it. He launched a preliminary search because experience taught him the difference between delay and disappearance.

The hinged sentence is this: in rescue work, the moment you stop hoping is the moment you start counting.

On March 16, volunteers and county search-and-rescue hiked to the base camp area. They found evidence someone had been there recently: a flattened section of snow where a tent might’ve been pitched, a few crampon marks near the approach gully, and an empty fuel canister half-buried in snow. The canister was the same brand Derek had purchased in town. It was enough to confirm he’d made it that far.

Beyond that point, the trail went cold.

The north face itself was a sheer wall of granite and ice over 1,200 feet tall—split by cracks, ledges, and chimneys requiring advanced technical skills. The team surveyed lower sections with binoculars. No bright colors. No gear. No movement. The rock was dark and shadowed; the snow blended into gray stone. If Derek was up there, he was invisible from the ground.

Over the next week, the search intensified. More volunteers arrived, including the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, a nonprofit specializing in high-altitude recovery. Some knew Derek personally. They’d shared belays, trusted him with their lives. Now they were searching for his.

Teams split. One worked lower cliffs, checking alcoves and behind boulders. Another climbed partway up the face to get a better vantage point. The stable weather shifted. Clouds moved in from the west. Wind arrived with scattered snow. Visibility dropped. Night temperatures fell to fifteen below. Radios crackled, then cut out, then crackled again. The mountain didn’t care what day it was.

On March 22, after nearly a week, the operation was suspended for safety. Sheriff Baxter held a press conference at the Granite Falls Community Center. He stood in front of a large map of the mountain, face lined with exhaustion.

“We’re pausing,” he said, “not stopping. We’ll resume when conditions allow.”

Jennifer sat in the back, hands folded tight, staring at the map like it might confess.

April brought a false spring. Valleys melted. High peaks stayed locked in winter. Search teams returned twice—mid-April and again at month’s end. Each time: nothing. No clothing, no abandoned gear, no tracks. It was as if Derek had dissolved into stone.

Theories spread because uncertainty demands stories. Fall and burial under snow. A crevasse. Summit and wrong descent. A planned disappearance—dismissed immediately by anyone who knew him. Derek wasn’t running from anything. He was moving toward something: a goal, a feeling, that moment of perfect focus the mountains could provide.

The hinged sentence is this: when the evidence goes quiet, imagination gets loud.

By May, local news moved on. Volunteers returned to their lives. The ranger station filed reports and closed the binder. But Jennifer didn’t move on. She stayed in Granite Falls, renting a small room above a hardware store on Main Street. She printed flyers with Derek’s photo and posted them at gas stations, trailheads, grocery stores. She walked trails herself—she wasn’t a climber, but she became a watcher—scanning cliffs with binoculars she bought at a thrift shop.

People recognized her: the woman in the gray jacket who never stopped looking up.

Sheriff Baxter told her privately what he believed. He said it gently, but with the firmness of someone who’d seen wilderness take people before.

“Jen,” he said, “I think he died up there. Fall or exposure. And… we may never recover him.”

She listened, nodded, then asked, “Can I borrow your high-powered spotting scope?”

Baxter hesitated. Then he agreed.

She set the scope on a ridge overlooking the north face and spent hours scanning—section by section, ledge by ledge—like devotion could become a tool. She kept a notebook with sketches of the wall, marking what she’d checked. Week after week, alone in silence, while the summer sun turned snow to water and water ran down the mountain in thin silver threads.

It was during one of those sessions that she said it out loud for the first time, as if speaking it could make it real.

“A drone,” she whispered.

Baxter’s department didn’t have the budget. “If you can find someone who can fly one up there,” he told her, “I’ll support it.”

Jennifer posted on climbing forums. Emailed tech companies. Messaged hobbyist pilots. Most ignored her. Some replied with sympathy. None offered a solution—until early June, when she received a message from Aaron Vest, a freelance videographer out of Denver. He’d done aerial filming for outdoor brands and documentary crews. He had a high-end drone built for wind and cold.

He didn’t ask for money.

“Send me the coordinates,” he wrote.

The hinged sentence is this: sometimes rescue arrives not as a siren, but as one stranger willing to say yes.

On June 18, 2017—three months after Derek vanished—Aaron drove to Granite Falls with his equipment. Jennifer met him at the trailhead just after dawn. The air was cool and still. The mountain wore a thin layer of mist like a veil.

Aaron was early thirties, quiet, methodical. He asked Jennifer to describe Derek’s planned route. She unfolded the map with hands that had learned to stop shaking only because shaking didn’t help. She traced the line up the north face.

Aaron studied it, then looked up at the wall. “I’ll start low,” he said, “work up grid by grid. We’ll record everything.”

Jennifer’s voice was small. “If he’s there…”

Aaron nodded once. “We’ll see him.”

He assembled the drone on a flat rock near the approach trail—four rotors, gimbal-mounted camera, bigger than Jennifer expected. He explained battery limits like a man reciting reality to keep it from becoming panic. “About twenty-five minutes per battery in these conditions,” he said. “Less if wind picks up. We’ll do multiple flights.”

The drone lifted off with a high-pitched whine and climbed until it cleared the pines. Aaron guided it forward, eyes fixed on the live feed. The camera showed rock in sharp detail: cracks, shadows, ice seams like white scars. He moved left to right, scanning in horizontal strips. First flight: nothing. Stone. Ice. The occasional stunted tree clinging to a crack like stubbornness.

He landed, swapped battery, launched again. Higher now, toward a diagonal ledge system that matched a feature on Derek’s route. The drone hovered close. Camera zoomed. Jennifer leaned over Aaron’s shoulder, breath shallow.

“You see anything?” she whispered.

Aaron didn’t answer right away. “Not yet,” he said finally. “But we keep going.”

Three more flights that morning. Each one higher. By noon, they’d covered roughly half the north face. Aaron scrubbed footage on his laptop, frame by frame, hunting for anything that didn’t belong.

Jennifer sat beside him on a boulder, hands wrapped around a thermos of coffee gone cold hours ago. She didn’t drink it. She just held it like a ritual.

Aaron paused on a section near the upper third of the wall. A shadow—darker than the others—tucked where two rock features met. He replayed, adjusted contrast, leaned in.

“Could be nothing,” he said.

Jennifer’s voice broke. “Or it could be him.”

Aaron marked the timestamp. “We’ll get a better angle,” he said, and his calm sounded like a promise he didn’t want to risk.

The hinged sentence is this: hope is a kind of math—one shadow plus one angle can equal a life.

After a short break, Aaron sent the drone up again, heading straight for the flagged area. The wind had picked up, and the drone wavered as it climbed, but Aaron kept it steady with small, precise corrections. He maneuvered closer, tilted the camera downward.

At first the image was grainy, backlit by sun. Then the shadows resolved into shapes.

Jennifer saw it before Aaron spoke.

A narrow, uneven ledge jutting out from the wall about 800 feet above the base. And on that ledge—someone sitting upright with their back against the rock, legs bent, one arm resting across their lap. Clothing torn and discolored, faded by months of sun and wind. A color that might once have been bright red or orange now looked like rust—almost the same shade as the stone.

The figure didn’t move.

Aaron inched the drone closer, as close as he dared without risking a collision. The camera focused. Details sharpened in a way that felt almost indecent, like the machine had no respect for grief.

The face was turned slightly downward, shadowed by the angle of light. Hair matted dark. One leg extended awkwardly as if injured. The other bent. Clothing hung loose. A climbing harness was still buckled around the waist, clipped to a sling anchored to a bolt in the rock. A rope trailed off the ledge, disappearing below—severed or frayed partway down.

Jennifer made a sound between a gasp and a sob and turned away, hand clamped over her mouth. Aaron kept the drone steady, recording. He didn’t say, “That’s him.” He didn’t need to. They both knew.

He flew a slow circle around the ledge, capturing angles. The ledge was roughly four feet wide and six feet long—a thin shelf in the middle of an otherwise unforgiving wall. No easy route up. No safe route down without technical gear. The figure faced the valley as if still watching the world below.

Aaron brought the drone back and landed it gently. He set the controller down like it was suddenly heavy.

Jennifer sat on the ground, knees pulled to her chest, staring at nothing.

Aaron crouched beside her. “I’m sorry,” he said quietly.

She nodded but didn’t look up. “Call the sheriff,” she whispered.

The hinged sentence is this: being found doesn’t undo the waiting—it only gives it a shape.

Sheriff Baxter arrived within an hour with two deputies and a search-and-rescue climber named Troy Whitman, who’d been part of the original efforts. Aaron replayed the footage on the laptop, slow enough to make every detail unavoidable. Baxter watched in silence, jaw tight.

When it ended, Baxter asked, “You sure about the location?”

Aaron pulled up GPS overlay. “Exact coordinates,” he said. “Northeast section, about two-thirds up.”

Baxter turned to Troy. “Can you reach it?”

Troy studied the rock features around the ledge, zooming in. “Possible,” he said. “Not easy. Either we climb from below or rappel from above. Conditions have to be right.”

“How long to organize?” Baxter asked.

“Two days,” Troy said.

Baxter nodded once. “Make it happen.”

He looked at Jennifer, still pale and streaked with tears. “You okay?”

Jennifer shook her head like the question didn’t fit the world anymore.

“Is there someone I can call?” Baxter asked.

“No,” she said, and it was true in the bleakest way.

“We’ll bring him down,” Baxter told her. “It may take time, but we will.”

“Thank you,” she whispered, and her voice almost disappeared in the wind.

The recovery began June 21, 2017. Six climbers from Rocky Mountain Rescue assembled at the base of Mount Silverton just after sunrise—ropes, anchors, pulleys, rescue litter, enough gear to build a system where the mountain offered none. Lead climber Vincent Taber, forty-two, two decades of rescue experience, knew the technical part would be hard. He also knew the emotional part would be heavier.

“Everyone ready?” Vincent asked over helmet radios.

A woman named Rachel Cove answered, “Ready.”

Another voice: “Let’s bring him home.”

They climbed most of the morning, placing protection, communicating in clipped words. Cold damp rock. Air smelling of iron and dust. By midday, Vincent and Rachel reached a point about fifty feet above the ledge. They built a multi-point anchor—bolts and cams—tested it, tested it again, because certainty mattered when the wall didn’t forgive mistakes.

Rachel clipped into the rappel line. “On rope,” she said.

“Copy,” Vincent replied. “Slow and steady.”

She leaned back over the edge and descended, boots scraping stone in controlled increments. As she neared the ledge, the figure became more real in a way the drone footage couldn’t fully deliver—human scale, human stillness. A man sitting upright, head tilted slightly, eyes closed. Clothing in tatters. Harness buckled. Rope end frayed and discolored where it had failed him.

Rachel touched down, clipped into Derek’s old anchor, and tested it. It held.

She knelt beside him and placed a gloved hand on his shoulder—not to check, not to hope, but to acknowledge.

Into the radio she said, voice professional but tight, “I’m at the site. Confirmed deceased.”

There were no obvious signs of severe impact. No dramatic injuries. It looked like exposure, exhaustion—slow forces that didn’t need violence to win. The position suggested he’d been conscious when he stopped, that he’d sat to rest, and at some point simply hadn’t gotten up again.

Rachel secured Derek to the rescue litter and wrapped him in a thermal blanket—not for warmth, but for dignity. She noticed details that made the story feel cruelly intimate: scraped hands, fingers curled as if still holding on, boots still laced though one sole had begun to separate, a small climbing camera clipped to his chest harness with a cracked lens but intact body.

She removed it carefully and tucked it into a pouch. “Camera recovered,” she told Vincent.

“Copy,” Vincent said, and the word sounded like relief and regret at once.

The haul took over three hours. The litter had to be guided around overhangs, across rough sections, through narrow gaps. Rachel climbed alongside it, guiding with a tag line so it wouldn’t swing. Below, team members watched through binoculars, faces grim.

Jennifer wasn’t there. Baxter had suggested she stay in town. For once, she agreed. “I don’t need to see him like that,” she’d said. “I just need to know he’s coming home.”

The hinged sentence is this: rescue isn’t always about saving a life—sometimes it’s about saving what’s left for the living.

By late afternoon, the litter reached the top of the technical section. They lowered it down the lower slopes, passing it from one person to the next until it reached the base. Vincent knelt, unclipped his harness, and stared at the blanket-wrapped form without speaking. There was no triumph. Only completion.

At the trailhead, a county medical examiner transport was waiting. Baxter shook each rescuer’s hand, thanking them quietly. Rachel handed over the camera. Baxter placed it carefully into an evidence bag.

“We’ll see if there’s anything on it,” Baxter said. “If there is, Jennifer will know first.”

Back in town, word spread the way it always does in small places. People stood outside the coffee shop, the lodge, the hardware store, watching the vehicle pass. Some bowed their heads. Some just stood in silence.

Jennifer waited at the sheriff’s office. Baxter led her into a small private room and closed the door. His tone was gentle, but it didn’t soften the truth.

“He was on a ledge high on the north face,” he said. “It looks like exposure. No sign he suffered a sudden trauma.”

Jennifer nodded, eyes red but dry, as if tears were a resource she’d already spent. “Did you… bring him down?”

“Yes,” Baxter said. “He’s being taken to the medical examiner in Ridgeway.”

“Can I see him?” she asked.

“Not yet,” Baxter replied. “They need time.”

He handed her a small bag of recovered effects: a carabiner, a water-damaged notebook, and—once it was processed—the camera would be returned. Jennifer held the carabiner in her palm like it might explain something. Then she looked at Baxter and asked the question that had been burning in her since March.

“Why didn’t he message me?” she whispered.

Baxter swallowed. “We don’t know yet,” he said. “But that camera might.”

The medical examiner, Dr. Howard Pine, documented everything methodically. No major fractures. No deep lacerations. Signs consistent with prolonged exposure. Mummification from cold, dry conditions. Scrapes on palms and fingers suggesting rope and rock work. The overall impression: a man who’d died slowly, not violently—cold, dehydration, exhaustion. Preliminary conclusion: hypothermia compounded by dehydration, possibly acute mountain sickness. Survived on the ledge at least several days, possibly longer.

Baxter read the report twice and placed it in the file. The mountains didn’t need malice. They only needed time.

The camera went to a digital forensics specialist in Denver, Ian Merrick, who’d recovered data from phones pulled from rivers and drives burned in fires. The climbing camera was damaged, but not beyond him. Two days later, he extracted partial files—images and short clips, some corrupted, timestamps possibly off.

Baxter reviewed them alone in his office, blinds drawn. The first images were wide shots of the north face under clear sky. Derek’s shadow stretched long on snow. Then time-lapse photos of the climb—hands on holds, boots wedged in cracks, calm face under helmet and sunglasses. He was making good progress. The ground fell away. Trees shrank. He paused at a ledge system, took a break, photographed the view like he couldn’t help himself.

Then the sequence shifted. Rock steeper. Ice thicker. Movements more cautious. In one clip, Derek’s breathing was heavier. He muttered, “Rock’s looser than expected.” He placed gear and yanked hard to test it before committing weight.

Then came the clip that explained the entire mystery, and Baxter felt his stomach tighten even before Derek finished the first sentence.

“Okay,” Derek said, voice tight with stress. “Okay. The anchor pulled. The whole thing just came out. I’m on the ledge now. I’m safe for the moment, but the rope is cut. I can see it down there just hanging. Must’ve caught an edge when the anchor failed.”

Wind battered the mic. Derek continued, working the problem out loud like that could hold panic at bay. “I got maybe sixty feet of rope left on this end. Not enough to rappel. Not enough to reach the next anchor point below. I’m gonna have to think about this.”

The clip ended.

Baxter watched the next images—photos of the ledge, the severed rope end fluttering, the blank wall above offering no clean route. Another clip, calmer but strained: “It’s getting dark. I’m gonna wait here tonight. I got my bivy, some food, water. Weather’s holding. I just need to stay calm.”

Another morning: pale overcast light. Derek’s hands photographed—red, swollen, fingers stiff. A half-empty bottle. The valley below like a different world. His voice, confidence gone: “I tried climbing up. No good. Too hard without more gear. Tried going down. Can’t reach the next anchor with what I got. I’m stuck. I sent a distress signal on the messenger, but I don’t know if it went through. Battery’s low. I’m gonna conserve it.”

Then, quieter, like he was talking to one person only: “If anyone finds this… tell Jennifer I’m sorry. I thought I could handle this. I really did.”

The hinged sentence is this: the cruelest trap is not being unseen—it’s being visible but unreachable.

The files became sporadic—shorter clips, fewer photos, Derek rationing power like he was rationing time. On March 15, he described trying to signal—reflecting sunlight with a small mirror, shouting until his voice gave out, rigging a makeshift anchor that didn’t work because the rope length wouldn’t let it. By March 16, his tone shifted from escape to endurance: nights brutal, snow scarce for melting, weakness creeping in.

“I keep thinking someone’s gonna come,” he said in one clip. “I keep looking down at the base, expecting to see people. But there’s nothing. Maybe they’re searching somewhere else. Maybe they think I made it to the top and went down the other side.”

A still image dated March 18 showed his face gaunt, eyes hollow, looking past the camera out into the valley. Not pleading. Not performing. Just watching.

The final clip, dated March 20, was barely a whisper. “I don’t think I’m getting out of this. I don’t think anyone’s coming. I tried. I really tried. I’m so tired. It’s hard to think… hard to move. I just want to sleep.”

A long silence. Wind. Shallow breath.

“Jennifer,” he said, voice breaking into air, “if you see this… I love you. I’m sorry I didn’t come home. I’m sorry.”

Then black.

Baxter sat in the dark office long after. He’d seen death in many forms, but this was a chronicle of a man realizing, day by day, that rescue wasn’t coming in time. Baxter made copies for evidence, wrote a detailed report: solo climber, anchor failure, rope severed, stranded on a narrow ledge approximately 800 feet above the base, survived at least eight days, attempted to signal, recorded messages. No foul play. No reckless behavior. An accident—bad luck and an unforgiving environment.

He called Jennifer that evening. “Can you come in tomorrow?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said without asking why.

The next morning, he warned her. “It’s difficult,” he said. “You don’t have to watch.”

Jennifer looked at him for a long moment. “I need to know,” she said. “I need to see what happened.”

Baxter played the files in order. Jennifer watched without looking away, hands folded in her lap, face so still it was almost frightening. When Derek’s voice came through the speakers, her breath caught. She didn’t cry loudly. She just seemed to go somewhere deep inside herself and bring back understanding like a thing with weight.

When the screen went black for the final time, Jennifer sat very still.

Baxter asked softly, “Are you okay?”

She nodded once. “I’m glad,” she said, voice thin, “that he could speak. That he… wasn’t just gone. It gives me something.”

“Not closure,” Baxter offered.

“No,” Jennifer whispered. “Understanding.”

The hinged sentence is this: grief doesn’t end when you learn the truth—it just stops arguing with the unknown.

The funeral was held on a warm afternoon in early July in a small chapel outside Boulder, pale wood and glass with the foothills visible through wide windows. It was the kind of place Derek would’ve liked—simple, open, the mountains present but not looming. More than a hundred people came: climbers, friends, coworkers from the outdoor gear company where he’d worked part-time, family from across the country.

Jennifer sat in the front row beside Derek’s parents, Gordon and Diane Pullman, both in their late sixties, faces worn down by a sorrow that didn’t need words. Gordon, retired engineer, had never understood Derek’s hunger for heights but never blocked it. Diane had always worried and always asked him to be careful, and now the worry had become a fact she couldn’t negotiate with.

The service was led by Lucas Grant, a climber friend who spoke about Derek’s meticulous preparation and respect for risk. “He didn’t climb to conquer,” Lucas said. “He climbed to find peace.”

People said the phrase “he died doing what he loved,” and usually it sounded empty. This time, it sounded true and still unfair.

Jennifer didn’t speak. She’d been asked. She’d declined. Some truths were too big for a microphone. Instead, she’d prepared a slideshow of photos—Derek on rock faces, at campsites, laughing with friends, staring into sunrises. There were no images from the camera. Those belonged to Jennifer alone.

Afterward, people gathered outside beneath cottonwoods. Coffee. Food. Low conversation. Jennifer stood at the edge where grass gave way to stone, eyes on distant peaks.

Sheriff Baxter drove in from Granite Falls and approached her quietly. “I’m sorry,” he said again, like apology could become a bridge.

“Thank you,” Jennifer replied, and then asked, “Any further findings?”

Baxter shook his head. “Case is closed,” he said. “The report and footage… it tells the story.”

Jennifer nodded. “Can I get the files?” she asked.

“We have a secure drive for you,” Baxter said. “At the office whenever you’re ready.”

Before he left, Baxter said something he’d been holding since watching those clips. “He did everything right,” he told her. “That anchor failure… he couldn’t have predicted it. This wasn’t a fatal mistake.”

Jennifer stared at the ridge line. “Understanding doesn’t make it easier,” she said.

“No,” Baxter admitted.

In the weeks after, Jennifer tried to return to normal life in the apartment she’d shared with Derek, but normal had left without telling her. His gear still hung in the closet. His books sat on the shelves. His coffee mug waited where he’d left it. She couldn’t move any of it at first. She spent evenings replaying the recovered videos, studying his face, listening to his voice change from calm to strained to resigned. She searched for something—maybe a sign he’d known how much she loved him, maybe a hint of peace.

One night in late July, she found a clip she hadn’t noticed before—timestamped March 19, only fifteen seconds. The image shook as if he’d been holding the camera by hand. Sky, pale and cloud-streaked, then the ledge, then his leg stretched out in front of him. His voice came through rough and faint.

“I saw a bird today,” Derek whispered. “An eagle, I think. Flew right past me. Close enough I could hear its wings. It didn’t even look at me. Just kept going like I wasn’t here. Made me think… maybe this is what it’s like to disappear. You’re still there, but the world moves around you like you’re already gone.”

Jennifer played it again. Then a third time. She closed the laptop and sat in the dark, listening to the city outside her window, thinking of that ledge and the thin line between being alive and being found.

In August, she made a decision. She couldn’t stay in Boulder surrounded by Derek’s things and all the places they’d planned to return to. She gave notice at her job, packed what she could, and donated most of Derek’s gear to a nonprofit providing equipment to young climbers who couldn’t afford it. She kept a few things: his favorite jacket, a journal from Peru, and the satellite messenger—empty now, screen dark, but still heavy with what it had failed to do.

Before she left Colorado, Jennifer drove back to Granite Falls one last time. She hiked to the spot where Aaron had launched the drone and stood at the base of the north face under late-summer sun, aspens beginning to turn gold. From the ground she couldn’t see the ledge. Too high. Too hidden by angle. But she knew it was there.

She held the silent satellite messenger in her palm and whispered Derek’s name into the wind—not as a plea, not as a curse, just as proof he had existed.

Then she turned and walked back down.

Months later, a small memorial plaque appeared at the trailhead, placed by members of Rocky Mountain Rescue. A simple bronze plate on a stone cairn: Derek Pullman, the dates, and one line—He climbed with courage and respect. People passing by often stopped to read it. Some touched the metal lightly with their fingertips, a quiet acknowledgment of a life that had been seen.

Sheriff Baxter retired the next spring. Aaron Vest kept filming the mountains and never spoke publicly about the case, but he carried the image of that ledge like something lodged behind his eyes. Rachel and Vincent continued rescue work, repeating the same hard truth in trainings: preparation matters, redundancy matters, and the mountain does not negotiate.

Jennifer settled in northern New Mexico, where the land opened wide into desert and sky. She didn’t climb again, but she walked long hikes where horizons felt endless and nothing rose above her like a wall. Sometimes she would pull the satellite messenger from a drawer and hold it for a moment—no power, no signal, just a smooth device that had once been a promise. Not a tool anymore, but a symbol: of an 11-minute call, of a vow made in love, of the thin line between checking in and never coming back.

The hinged sentence is this: sometimes the only way to survive what you lost is to carry it gently, not loudly.

News

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO”

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO” It…

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He Kil.. | HO”

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He…

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You | HO”

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You |…

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO”

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO” Her…

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO

THE BILLIONAIRE’S SON WAS BORN BLIND — WHAT HE SAW THE NEW MAID DOING SHOCKED HIM | HO “How,” he…

End of content

No more pages to load