Experts analyzed this 1857 image — zooming in on one of the slaves reveals a horrific detail | HO!!

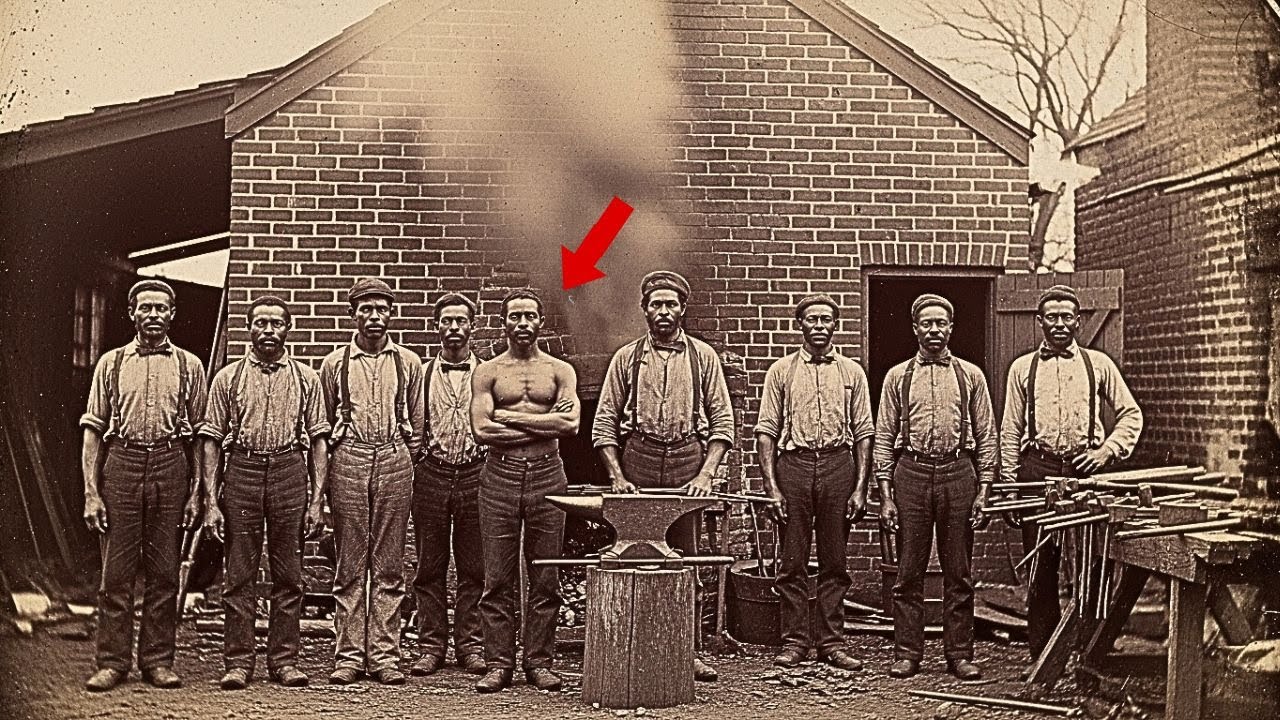

At first glance, the 1857 photograph appeared to be an ordinary record of labor — eleven men standing outside a forge, their faces smeared with soot, their eyes fixed on the camera.

Taken on Riverside Plantation, along the James River near Richmond, Virginia, the image bore a simple caption written in neat cursive:

“Iron Works, March 1857.”

But when Dr. Rachel Morrison, a curator at the Virginia Historical Archive, placed the photo under a digital microscope, she froze.

On the left shoulder of the fifth man — a tall, broad-shouldered figure standing slightly apart — was a mark. Not a scar, not an accident, but a brand.

And not just any brand.

It was shaped like an anvil.

Rachel had examined thousands of images of enslaved laborers during her career. But she had never seen anything like this.

The Branded Blacksmith

The man’s posture was strong, defiant even, his arms crossed over his chest as if shielding himself from humiliation. The torn edge of his shirt revealed the burned outline clearly — an ironworker’s tool burned into human skin.

Rachel snapped several photographs and immediately sent them to Professor David Chen, an expert on punishment and resistance in the antebellum South. His reply came within an hour.

“I’ve seen letters, initials, even numbers branded onto enslaved people. But an anvil? That’s not ownership — that’s a message. We need to talk.”

By the next morning, David was at the archive with stacks of plantation records and grim fascination in his eyes.

“Isaac Branded with the Anvil Mark”

Riverside Plantation had been one of Virginia’s largest industrial estates before the Civil War — a place where human beings and iron were both forged under heat and pressure.

Rachel began combing through the Overseer’s Journal of 1856, its pages brittle and stained with smoke. One entry, dated October 15th, caught her eye:

“Discovered blacksmith Isaac fabricating implements not authorized by Master Thornton. Hidden cache of files and chisels suitable for breaking shackles and locks. Reported immediately.”

Three days later, the next entry:

“Master Thornton ordered severe punishment. Isaac branded with anvil mark as warning to others. Tools of his trade turned against him. Forbidden from forge but reinstated due to necessity of skill.”

Rachel’s throat tightened as she read aloud. “Tools of his trade turned against him.”

David nodded grimly. “The anvil wasn’t random. It was meant to humiliate — to mark him as a craftsman who betrayed his purpose. But it also says something else: they needed him too much to kill him.”

The Escape Plot

They dug deeper.

Plantation ledgers revealed that Isaac and his father had been purchased together in 1840 for the enormous sum of $2,400, described as “skilled blacksmiths of exceptional talent.”

Isaac’s work supported not just Riverside’s operations but neighboring plantations. He produced decorative gates, complex hinges, and even precision parts for early steam engines. Letters from local planters praised “the artistry of Thornton’s smith.”

But buried among the glowing records was a darker line of correspondence — October 12th, 1856:

“Conspiracy discovered among the workers. Implements for breaking locks found in several quarters. Recommend neighboring plantations inspect their smithies.”

The escape attempt failed. Five men — Isaac, Daniel, Joseph, Marcus, and Thomas — were punished. Isaac, as the ringleader, was branded. The others were sold away, scattered to distant states.

Riverside’s overseer noted coldly:

“All troublesome elements removed. Isaac remains, as no replacement matches his proficiency.”

The Mark That Spread

Over the following months, Rachel and David traced what happened next — and discovered something extraordinary.

Across Virginia in late 1857, overseers began reporting mysterious carvings: anvils scratched into barn walls, symbols on prayer benches, patterns burned into leather belts.

At first, plantation owners dismissed them as meaningless doodles. But then a letter surfaced from a Quaker teacher in Richmond, Abigail Foster, who secretly educated free Black laborers.

Her diary, dated June 1857, read:

“A man attended class wearing a small medallion carved with an anvil. When I asked its meaning, he said quietly, ‘It reminds us that chains can be broken.’”

David leaned back, stunned. “They turned his punishment into a symbol of resistance.”

The mark that had been meant to shame Isaac became a secret emblem — a coded sign passed between those who dreamed of freedom.

The Anvil Code

Rachel uncovered a letter from a Methodist minister complaining to church officials in 1858:

“Among the colored congregants, I observe crude images of anvils scratched into pews and hymnals. They claim it signifies honest labor, but I suspect darker meaning.”

The “darker meaning” was solidarity. The anvil had become the quiet pulse of rebellion — a way for the enslaved to recognize allies and mark safe places along the Underground Railroad.

Dr. Sarah Williams, a historian specializing in those networks, joined the project. She mapped a constellation of recorded escape routes across Virginia from 1856–1860.

“Notice this cluster,” she said, tracing her finger along a stretch of the James River. “Every route that succeeds originates within a hundred miles of Riverside Plantation. That’s Isaac’s territory.”

The Blacksmith’s Secret Network

Riverside’s ledgers from 1857 onward showed a peculiar pattern — iron stock purchased but never fully accounted for.

In March 1857, 300 pounds of iron arrived at the forge. Only 270 pounds were reflected in finished tools. The same discrepancies appeared month after month.

“Thirty pounds of missing iron every month,” Rachel murmured. “That’s not error — that’s production.”

David nodded. “He’s making something — and hiding it.”

The overseer’s journals mentioned growing frustration with “damaged files and chisels discarded for remelting.” But what if those tools weren’t truly damaged?

Sarah explained that Underground Railroad networks often used such tricks — tools hidden in plain sight, disguised as waste, then retrieved by intermediaries.

Isaac, under constant watch, had found a way to keep forging freedom — one file, one chisel, one pry bar at a time.

The Anvil Man

In the Freedmen’s Bureau archives, Sarah found postwar testimonies collected from formerly enslaved people.

One account, from a man named Solomon, mentioned an almost mythic figure:

“There was a blacksmith with an anvil burned into his skin. They called him the Anvil Man. He made the tools we used to break chains. We never saw him, but we knew he was there. If you found the mark carved in a tree, it meant help was near.”

Rachel realized the symbol had evolved beyond Isaac himself. His mark had become a signal of hope — a language written in iron and pain.

By 1860, Union spies and abolitionist groups documented dozens of “anvil-marked caches” across Virginia — hidden bundles of tools and provisions guiding fugitives northward.

Even slaveholders began to notice. One planter near Fredericksburg complained bitterly in 1859:

“Runaways now equipped with files and pry bars of professional quality far beyond their capacity to produce.”

The War and the Irony

When the Civil War erupted in April 1861, Isaac’s world changed again.

Riverside’s forge was conscripted into service for the Confederate war effort — producing wagon parts, tools, and weapons components. The overseers could no longer afford to hover over him constantly.

In an 1861 letter, Edward Thornton — the man who had branded him — wrote:

“Given the demands of war, I have relaxed oversight of forge operations. Isaac remains loyal and industrious. His skill is indispensable.”

Rachel paused over the words. “He was helping supply the Confederate army — the same army fighting to keep him enslaved.”

David shook his head. “And yet, I bet he kept helping others too. Just quieter this time.”

Freedom Forged in Fire

After Richmond fell in 1865, Union officers documented the region’s surviving industrial sites.

In an April report, Captain William Bradford of the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry wrote:

“Visited Riverside Plantation. Found an enslaved blacksmith, approximately forty years old, bearing an anvil-shaped brand. Exceptional skill. Upon being informed of his freedom, he requested permission to continue working to make tools for freedmen starting new lives. I have authorized him to remain and operate as a paid craftsman.”

For the first time, Isaac’s name reappeared in official records — not as property, but as a man.

Two months later, a Freedmen’s Bureau report added:

“The blacksmith Isaac at Riverside produces fine tools distributed to freed families. When thanked for his generosity, he replied, ‘I know what freedom requires.’”

The Testimony

The most powerful discovery came from a Union Army commission transcript in June 1865 — Isaac’s own words:

“I was branded in ’56 for helping men seek their liberty. They said I had betrayed my master’s trust, but I believe I honored a higher one. The mark they gave me — I made it my reminder. Every time I saw it, I remembered who I was working for. I could not save them all, but I saved some.”

Rachel closed the file slowly. “He turned his scar into a purpose.”

David whispered, “He turned his punishment into a movement.”

The Legacy of the Anvil

Isaac Freeman — the name he chose for himself after emancipation — ran the Riverside forge until 1870, crafting tools for freed Black farmers and teaching apprentices.

By the time of his death in 1889, census records listed him as “blacksmith, literate, respected member of community.”

In a Richmond newspaper obituary, one line stood out:

“Mr. Freeman carried the mark of bondage upon his shoulder, yet forged from it a symbol of freedom.”

The Exhibition

Today, the Virginia Museum of History displays the restored 1857 photograph as the centerpiece of an exhibition titled “Tools of Freedom: The Story of Isaac, the Branded Blacksmith.”

A high-resolution enlargement of his shoulder fills an entire wall — the anvil brand visible in haunting detail. Beside it, museum artisans have recreated the tools Isaac once forged in secret: slender files, disguised pry bars, hollow-handled chisels — the literal instruments of escape.

A digital map illuminates the network of anvil symbols that spread from Riverside to the Appalachian foothills, tracing a constellation of resistance that endured long after Isaac’s death.

During the exhibit’s opening, descendants of those he aided came forward. One elderly man, James Patterson, brought a small wooden pendant shaped like an anvil.

“My great-grandfather escaped from Virginia in 1858,” he said quietly. “He always wore this. We never knew why — until now.”

The brand meant to destroy Isaac became a beacon.

The photograph meant to record labor became evidence of rebellion.

And in the grain of that old 1857 image, history’s silence broke — revealing that even in bondage, a man of iron could forge freedom itself.

News

Husband Won $99,800 In The Lottery, Wife Kills Him To Take The Money For Herself | HO!!

Husband Won $99,800 In The Lottery, Wife Kills Him To Take The Money For Herself | HO!! For years, Curtis…

A Woman’s Affair With Her Cousin’s Husband Ends In D3ath | HO!!

A Woman’s Affair With Her Cousin’s Husband Ends In D3ath | HO!! In the late summer of 2023, the quiet…

He Thought His Wife D!ed In A Car Crash. Three Years Later, She Was Found Alive In Another State | HO!!

He Thought His Wife D!ed In A Car Crash. Three Years Later, She Was Found Alive In Another State |…

Bumpy Johnson’s Bodyguard PULLED THE TRIGGER at Point Blank Range — This Sound Changed History | HO”

Bumpy Johnson’s Bodyguard PULLED THE TRIGGER at Point Blank Range — This Sound Changed History | HO” At 11:47 p.m.,…

Reggae Star Spice REVEALS Some DARK SECRETS She’s BEEN HIDING! | HO!!

Reggae Star Spice REVEALS Some DARK SECRETS She’s BEEN HIDING! | HO!! For more than two decades, Spice has been…

95 Days After She Visited Her Boyfriend In Bahamas, She Was Tested 𝐇𝐈𝐕+, Her Revenge Made 21 Women.. | HO!!!!

95 Days After She Visited Her Boyfriend In Bahamas, She Was Tested 𝐇𝐈𝐕+, Her Revenge Made 21 Women.. | HO!!!!…

End of content

No more pages to load