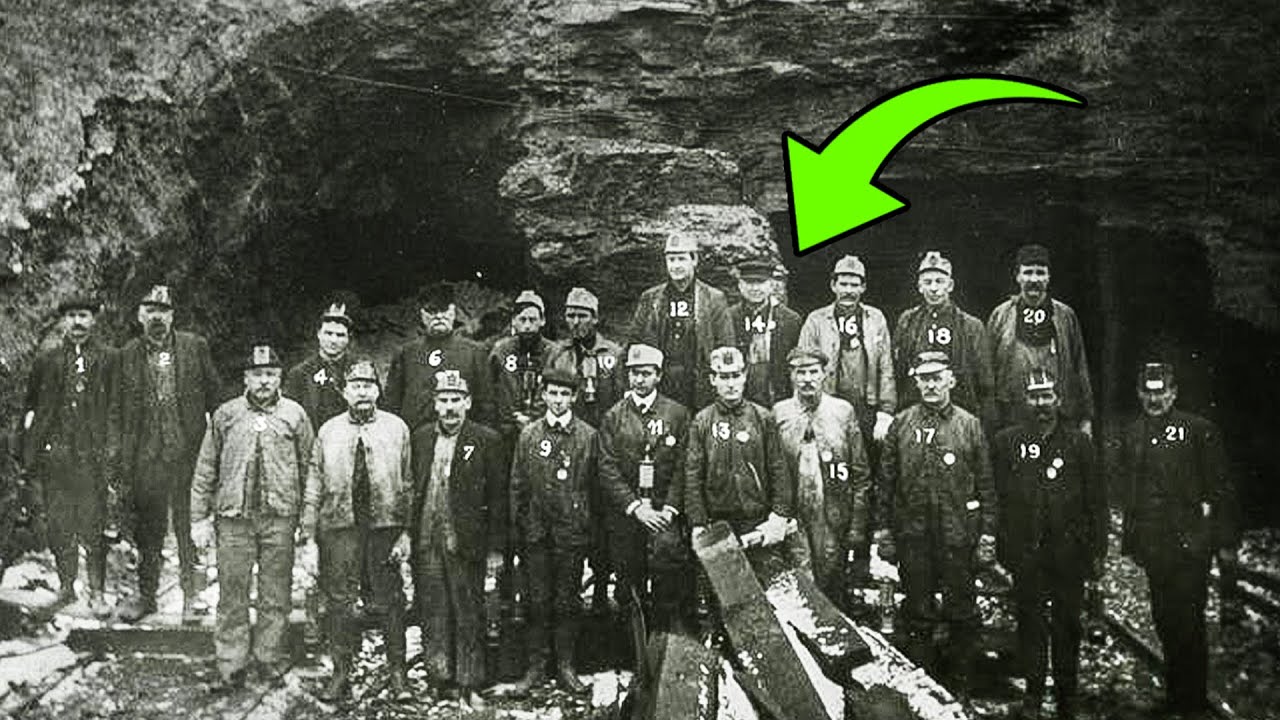

Experts Thought This Was Just a Normal Photo of Coal Miners From 1907… They Zoom In & Turn Pale | HO!!

The photograph had slept in the darkness of an archive box for longer than anyone alive had existed. Dust coated its edges. The ink had faded into the soft sepia haze that old images acquire when they have been forgotten for too long. No one expected anything unusual from it. After all, it was one of hundreds—maybe thousands—of coal mining photographs donated to the Pennsylvania Mining Heritage Foundation over the decades.

But all it took was one woman, one glance, and one instinct that refused to be ignored.

Dr. Sarah Chen had spent three years cataloging photographs for the foundation. It was quiet work, the kind that demanded patience, precision, and the ability to look at the same bleak scenes—miners covered in coal dust, rickety mine entrances, exhausted families—day after day without letting the sadness sink too deep into the bones. She thought she’d gotten used to it. She thought nothing could shock her anymore.

She was wrong.

It was a rainy October afternoon when she found it. The sky was the color of cold metal, the office smelled faintly of mildew, and Sarah had already decided she would leave ten minutes early. Her eyes were tired, her fingers stiff. She pulled one more photograph from the box—just one more before she allowed herself the relief of stepping outside.

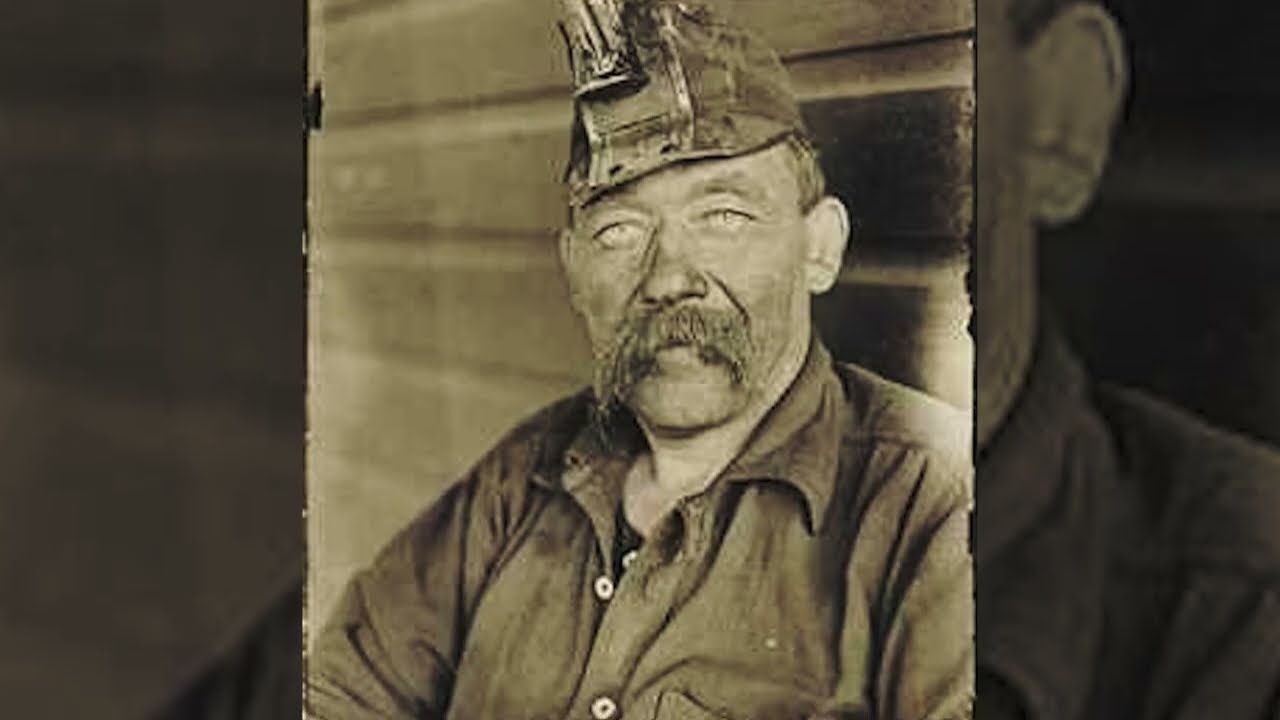

At first glance, it was nothing special. A group portrait of coal miners from 1907. Twenty-one men arranged in two rows, standing before the yawning black mouth of a mine carved into the Allegheny rock. Their expressions were typical: stoic, weary, resigned. The faces of men who labored in darkness so deep that sunlight felt like a dream.

She almost set it aside.

But something tugged at her. A whisper in the back of her mind. A sensation historians learn to listen to, because history does not reveal its secrets to those who rush.

She pulled the photograph back.

Turned on her high-resolution scanner.

Zoomed in.

And then her world shifted.

In the second row, behind a heavyset man with a broken nose, stood three figures—ordinary at first glance, until the screen enlarged their faces. Sarah’s heart stopped. Her breath vanished.

These weren’t men at all.

Under the caps. Beneath the dirt. Behind the soot-streaked cheekbones.

They were women.

One of them—number 14 in Sarah’s notes—was barely more than a girl.

When Marcus, her colleague, leaned in beside her, his face drained of color instantly. “No,” he whispered, “that can’t be right.”

But it was right.

The longer they stared, the more unmistakable it became. The soft curve of a jaw poorly hidden beneath coal grime. The delicate bone structure, the shape of the mouth, the youth, the truth that no amount of dirt could disguise.

This photograph, taken in one of the most dangerous professions of the early 20th century, hid a secret no historian had ever documented. And once Sarah and Marcus understood the truth, they were unable to unsee it.

These were women dressed as men.

Women who had gone underground.

Women who had risked their lives for reasons history had buried.

Women who had survived one winter that should have swallowed their families whole.

The story that Sarah would soon uncover was not one of curiosity or novelty. It was one of desperation. Of broken systems. Of sacrifice quiet enough that no newspaper had ever recorded it.

A story that began five months before that photograph was taken.

The winter of 1906 in the Allegheny Mountains was merciless. Temperatures plunged so low that livestock froze standing. The Delaware River turned solid, trapping boats in glass. Families huddled around dwindling firewood. Hunger gnawed like a vicious animal.

In the mining towns, the crisis was even worse. Coal mining was hard enough in good weather. But during that winter, avalanches closed roads. Supply carts couldn’t reach remote settlements. The wages of miners who were paid by the ton rather than the hour shrank to nearly nothing, because even reaching the coal face was nearly impossible in the bitter cold.

That was the winter when James O’Sullivan’s leg was crushed in a cave-in.

He had been underground for nearly thirty years, and he’d always told his children that the mines had a voice, a way of warning you. But on that day, the warning came a second too late. A single crack, then darkness. He survived only because two younger men dug him out with their bare hands, screaming his name over the roar of collapsing stone.

He would never work again.

His 17-year-old daughter, Margaret O’Sullivan, watched the doctor splint the leg. Watched her mother cry quietly at the stove, her younger siblings shivering beneath blankets. Watched her father apologize for something that was not his fault.

And then she made a decision.

A decision that would become the heart of the photograph that stopped Sarah Chen’s breath 113 years later.

Margaret cut her hair at dawn.

She used her father’s dull razor and tried not to cry as each lock fell. She dressed herself in his jacket—far too large—his suspenders, his cap.

When she stepped into the freezing air, she was trembling. Not from cold.

From fear.

At the mine entrance, the foreman, Thomas Brennan, squinted at her through the dim light. He had worked underground since he was twelve years old. He’d broken ribs, lost friends, buried pieces of himself far beneath the mountain. He didn’t scare easily.

But something about the girl with the too-big jacket and the fire in her eyes struck him like a hammer.

“I know who you are,” he growled. “Go home, girl.”

Margaret swallowed. Her voice shook, but she spoke anyway.

“My father can’t work. My mother is sick. My brothers are little. And my sister is four years old. If you don’t let me earn a wage, Mr. Brennan… then you can explain to Reverend Matthews why children starve this winter.”

Her breath fogged in the air. Her hands trembled.

She stood her ground.

And in that moment, Thomas Brennan broke a rule he’d lived by his entire life.

He looked the other way.

“Keep your eyes down,” he muttered. “Keep quiet. And if anyone asks—”

“I’m Michael O’Sullivan,” she said quickly. “James’s nephew from Pittsburgh.”

He nodded once.

And Margaret O’Sullivan stepped into the darkness.

What Margaret didn’t know—what Sarah Chen would discover decades later—was that she was not the only woman wearing borrowed clothes and risking her life beneath the mountain.

In fact, she was the third.

Standing in that photograph, her shoulders squared, her face steady despite all she’d lost, was Katherine Kowalsski. Twenty-eight years old. Widow. Mother of three. Her husband had died in a shaft collapse in November 1905, buried under tons of rock. She received $14 in compensation. Fourteen dollars to raise three children.

The mine store evicted widows after three months if they fell behind in payment. Katherine was two weeks from being thrown out into the snow.

So she became “Carl.”

She worked without complaint.

Without rest.

Without allowing grief to consume the one thing keeping her children alive.

To the men beside her, she wasn’t a curiosity. She wasn’t a threat. She wasn’t a scandal.

She was a mother, fighting for her family.

And that was enough.

The third woman in the photograph—Elizabeth Lee—carried a different story, but one no less heartbreaking.

She had crossed the entire country after the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906 destroyed her home, killed her husband, and left her wandering with only the clothes on her back. Her grandmother had once told her stories of Chinese women who disguised themselves as men to fight in ancient wars, to travel freely, to survive in worlds that tried to shrink them.

So Elizabeth reinvented herself again.

She arrived in Pennsylvania with nothing, stepped off a train into a town where no one knew her, and walked straight into the mine office to apply for work.

No disguise of desperation—just determination.

She earned respect quickly.

But respect could not erase danger.

Or hide exhaustion.

Or prevent tragedy.

And tragedy was coming.

The photograph was taken on April 2, 1907. The first warm day after a brutal winter. Snow melted in the fields. Birds returned to the pines.

The mine reached record production. Spirits were high. Someone—most likely Thomas Brennan—insisted on photographing every worker.

It was intended as a celebration.

It became a memorial.

Five weeks later, the mountain roared.

A tunnel collapsed without warning, sending shockwaves through the ground. Fourteen miners were trapped in a chamber that rapidly filled with choking dust. The rescuers worked nonstop, clawing through unstable stone while the mountain groaned ominously above them.

The newspapers later called it “a miracle.”

But the true miracle was kept out of the headlines.

One of the rescuers who volunteered to crawl into the narrowest part of the collapsed shaft—where the rock above could have crushed her instantly—was Margaret O’Sullivan.

She wriggled through gaps too small for most men. She dug with bleeding hands. She shouted encouragement through cracks in the stone.

She stayed until her voice broke, until her fingernails tore away, until the last man was dragged out.

Thomas Brennan watched her emerge from the darkness—dust and blood coating her hair, tears carving streaks down her soot-blackened cheeks—and he wrote something in his diary that Sarah discovered in a box decades later:

“Today I saw true courage. It does not always come in the form we expect.”

He never reported her.

He never exposed Katherine.

He never betrayed Elizabeth.

Some secrets, he believed, were acts of mercy.

When Sarah found that diary entry more than a century later, she cried in the silent archive room, tears falling onto the wooden table.

Because suddenly, the photograph was no longer just an anomaly.

It was a testament.

A testament to bravery that no one honored.

To sacrifice no one acknowledged.

To women who carried families on their backs while the world told them they had no right to stand among men.

Sarah’s exhibition six months later included the photograph, the diary, the letters, the census records, and—most importantly—the stories of the three women who risked everything.

Visitors traveled across the country to see it.

Descendants came forward.

One elderly woman—Patricia O’Sullivan, Margaret’s granddaughter—pressed her hand to the glass and whispered:

“There she is. Seventeen years old. Feeding five siblings. Braver than anyone gave her credit for.”

Margaret lived to be 92.

Katherine lived long enough to see all three of her children married.

Elizabeth became a successful boarding house owner, her strength echoing through generations.

But none of them ever spoke of the mines.

Not once.

They kept that winter buried inside them, the same way the photograph had been buried in a box for more than 100 years.

Looking at the image now—the three women standing shoulder to shoulder with men who protected them, who worked beside them, who knew and kept their truths—one realization hits hardest:

Some of the greatest acts of courage in history are invisible.

They happen in silence.

In darkness.

In tunnels beneath mountains.

In the hearts of people who choose survival not because they want to be heroes, but because they have no other choice.

Experts thought this was just a normal photo of coal miners from 1907.

But when they zoomed in, they uncovered a story of hunger, sacrifice, sisterhood, and a quiet rebellion against a world that gave women no power—yet depended on their strength.

The photograph did not change history.

It revealed the history that had always been there.

Hidden in plain sight.

Waiting for someone to look closely enough.

News

Woman Born in 1843 Talks About the One Thing She Regrets Most – Enhanced Audio | HO

Woman Born in 1843 Talks About the One Thing She Regrets Most – Enhanced Audio | HO I think about…

Teen K!ller Laughs in Judges Face, Thinking He’s Undefeated — Then His Grandmother Stands Up | HO

Teen K!ller Laughs in Judges Face, Thinking He’s Undefeated — Then His Grandmother Stands Up | HO “Mr. Cole,” Judge…

This Baby Isn’t Ours’—Her In-Laws Beat the Widow Until a Cowboy Rode In | HO

This Baby Isn’t Ours’—Her In-Laws Beat the Widow Until a Cowboy Rode In | HO Sometimes salvation rides in so…

Dad 𝐀𝐛𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 His 𝗗𝗜𝗦𝗔𝗕𝗟𝗘𝗗 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 With Mother’s APPROVAL—She Got 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗻𝗮𝗻𝘁, They Did THIS to Hide It | HO

Dad 𝐀𝐛𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 His 𝗗𝗜𝗦𝗔𝗕𝗟𝗘𝗗 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 With Mother’s APPROVAL—She Got 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗻𝗮𝗻𝘁, They Did THIS to Hide It | HO On a…

10 Hours After She Left With Her New BF For Hawaii, He K!lled Her When She Discovered He Had.. | HO

10 Hours After She Left With Her New BF For Hawaii, He K!lled Her When She Discovered He Had.. |…

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!!

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!! Andre Johnson. Inmate #44702….

End of content

No more pages to load