Ezekiel the Rebel: The Slave Who Led an Uprising, Killed His Master, and Married the Daughter | HO

I. The Vanishing Plantation

In the spring of 1857, federal marshals arrived in Clark County, Mississippi, to investigate something that shouldn’t have been possible.

An entire plantation—three hundred acres of prime cotton land known as Thornwood—had vanished. Not burned, not sold, not foreclosed.

Vanished.

The county ledgers showed a blank space where Thornwood’s name should have been. The census takers had skipped it entirely. Even the land deeds, normally precise to the inch, contained a silence—a void in ink—as if the property had been erased from history itself.

Neighbors said it had burned in an accident. Others whispered of rebellion, of madness, of a curse. But when marshals reached the site, they found only ash, fragments of whitewashed timber, and a handful of terrified witnesses who all told the same story:

“The master’s daughter was murdered. The slaves rose up. Then the whole place burned.”

For more than a century, that was the official version. A tragic warning about what happened when masters lost control of their plantations.

But in the late 1940s, a historian named Dr. Eleanor Winters uncovered something extraordinary—a manuscript buried in the dry soil of northern Mexico.

It was written in two hands, one masculine, one feminine, and it told a story that turned the accepted version of Thornwood inside out.

The authors called it The Thornwood Record.

And within its pages lay the confession of a man history had only whispered about: Ezekiel, the enslaved field hand who became a teacher, a strategist, a murderer—and a husband to his master’s white daughter.

II. A Land Built on Fear

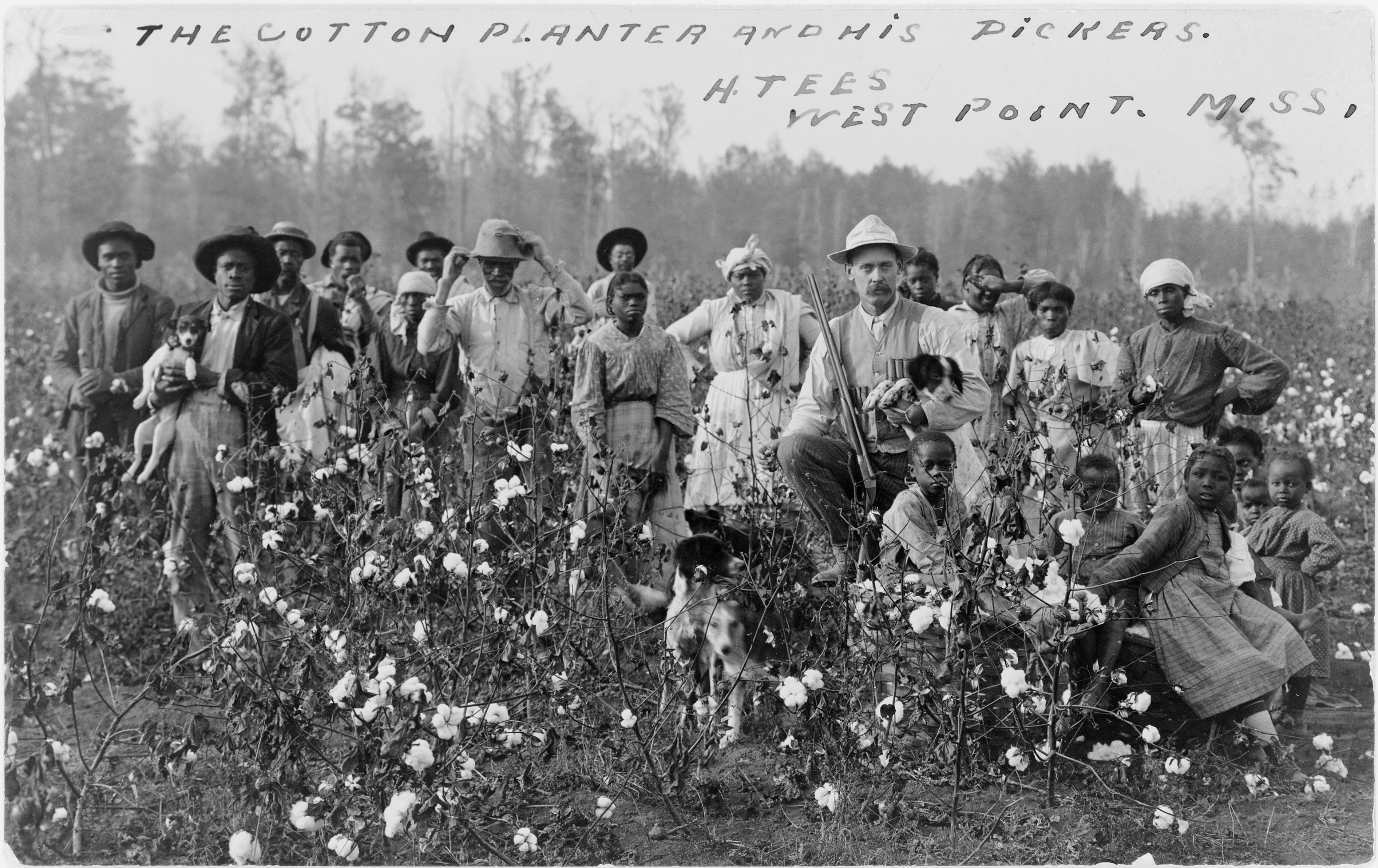

Clark County, Mississippi, in 1853 was a place where cotton grew taller than a man and fortunes were measured by the broken bodies of those forced to harvest it.

Thornwood Plantation sat three miles east of Quitman, a modest estate by local standards—ten rooms, twelve slave cabins, and 280 acres of black earth that bled red after rain.

Its master, Marcus Thornwood, was forty-eight years old, a man born into debt and determined to buy respectability through cruelty.

He wasn’t rich enough to be arrogant nor poor enough to be humble.

He was a desperate man in a desperate system, and desperation has a way of breeding monsters.

His only daughter, Catherine Thornwood, was twenty-three—educated, intelligent, and quietly fractured.

Her mother had died when Catherine was nine, leaving her to be raised by a father who loved her property more than his child.

She’d studied at the Madison Female Academy, learned French and philosophy, and—most dangerously—had been exposed to the radical idea that liberty meant everyone.

But education could not erase inheritance. Catherine came home to Thornwood in 1850 and resumed her role as the obedient daughter of a man who owned forty-seven human beings.

And among those forty-seven was Ezekiel, age twenty-four, purchased in 1848 from a broker in Natchez.

Strong. Literate. Dangerous.

That last word wasn’t in the bill of sale, but it might as well have been.

III. The Literate Slave

Ezekiel had learned to read in secret from the son of a previous master—a sickly boy who died young but left behind a living gift.

Letters became his weapon, paper his map, literacy his rebellion.

On Thornwood Plantation, Ezekiel picked cotton by day and observed by night. He watched Marcus’s patterns—how much he drank, how often he lied to creditors, when he forgot to lock his study. He learned every path through the woods, every weakness in the fences, every man who could be trusted to whisper in the dark.

By 1853, Ezekiel had turned Thornwood’s quarters into a school.

Under the pretense of evening prayer, he taught other enslaved people to read. He used scraps of newspaper, charcoal, and bark.

He didn’t just teach letters—he taught strategy.

He told them that slavery was not ordained by God or nature. It was constructed.

And what was built by men could be destroyed by them.

IV. The Promotion

Marcus’s downfall began with a theft. His overseer, a brute named Briggs, had been skimming cotton and selling it privately. When Marcus discovered the fraud, he fired Briggs in a rage—and suddenly found himself without anyone to run the fields.

Hiring a new overseer cost money he didn’t have.

So he made a catastrophic decision.

He promoted Ezekiel.

At breakfast, Catherine had protested.

“Father, giving authority to a slave—especially an educated one—”

Marcus waved her off. “He’ll be grateful. It’ll secure his loyalty.”

Ezekiel accepted the promotion with bowed head and lowered eyes.

But in that moment, everything changed.

He now had keys, access, and power—the kind that moves unseen.

By day, he managed the fields flawlessly, earning Marcus’s trust.

By night, he became something far more dangerous: an organizer.

Within months, Thornwood was two plantations—one visible to the master, one invisible beneath him.

V. Catherine’s Awakening

Catherine first noticed the change by accident.

One night she approached the kitchen house and heard voices—low, rhythmic, deliberate.

When she peered inside, she saw Ezekiel teaching letters to a group of children, the flicker of candlelight on their faces.

She should have turned away. Reporting him would have earned her father’s praise.

Instead, she stood frozen, listening to the soft chant of freedom disguised as phonetics.

That night, Catherine did not sleep.

Within weeks, she began secretly aiding him.

She lent books, maps, documents—materials she knew could get them both killed.

When Ezekiel asked her why, she answered with a truth that would haunt her for the rest of her life:

“Because I know what words like all men are created equal are supposed to mean.”

It wasn’t a declaration. It was an awakening.

VI. The Murder

The turning point came in December 1853.

A young enslaved girl named Mary from a neighboring plantation was captured after escaping her master’s son.

They whipped her in the public square. Forty lashes.

Catherine watched from a shop window as the girl was dragged past, and she vomited afterward.

That night, she told Ezekiel she was done pretending.

He told her there was only one way forward.

Her father had to die.

They planned it carefully: a glass of whiskey, a pillow, and silence.

On January 28, 1854, Catherine poured her father’s drink and waited until he slept.

Ezekiel joined her in the doorway, the pillow trembling in her hands.

“Last chance,” he whispered.

“Together,” she said.

Three minutes later, the master of Thornwood was dead.

Catherine collapsed, gasping.

“I killed my father.”

Ezekiel placed his hand on her shoulder.

“You killed a master. You freed forty-seven souls.”

And so began the most dangerous experiment in American history.

VII. The Paper Revolution

The next forty-eight hours were chaos disguised as order.

Ezekiel gathered everyone in the largest cabin. Catherine stood beside him—white, trembling, complicit.

“Marcus Thornwood is dead,” Ezekiel announced. “But we can make his death mean something.”

They forged everything—wills, manumission papers, letters, and diary entries.

Under Catherine’s hand, Marcus was reborn on paper as a repentant man who had freed his slaves in his final days out of Christian guilt.

It was audacious, blasphemous, and brilliant.

When the local doctor certified Marcus’s death as “heart failure due to drink,” their deception was complete.

Within a week, Catherine had filed the forged will.

To the world, she was a grieving daughter carrying out her father’s last wishes.

To the people of Thornwood, she was something else entirely—a comrade.

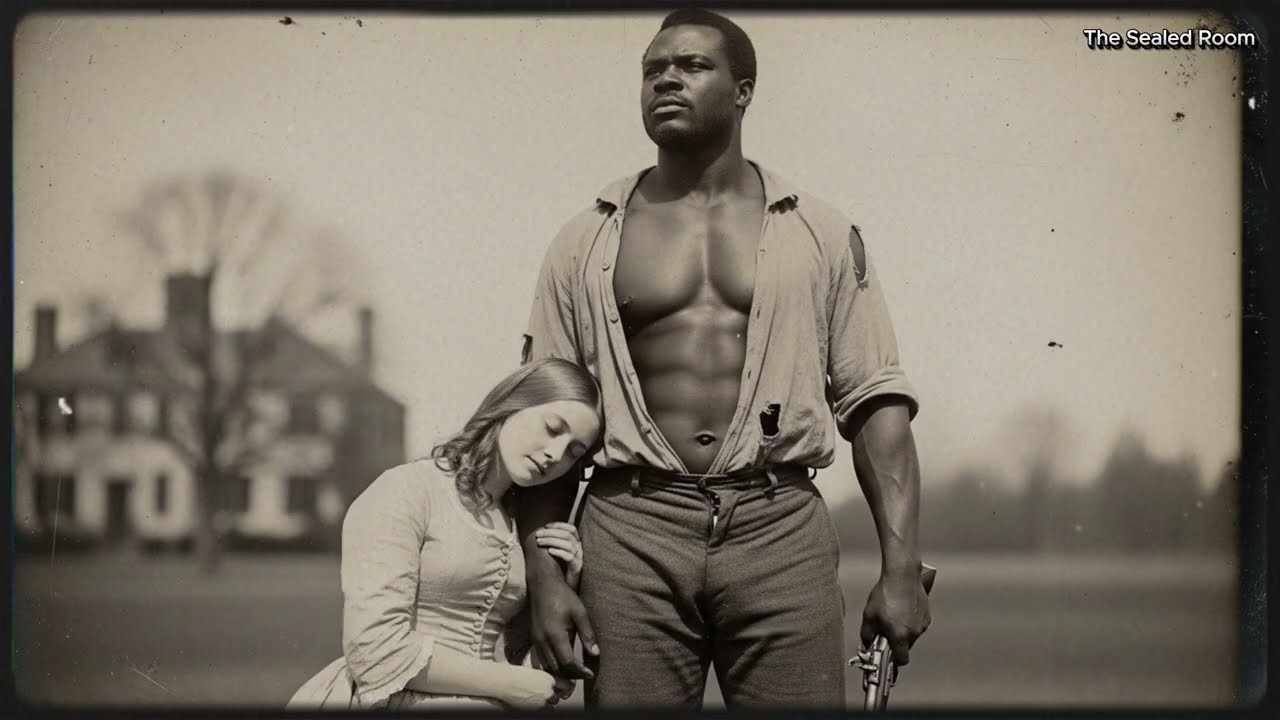

![]()

VIII. The Commune

What followed was seven months of fragile utopia.

Catherine’s plantation became the only one in Mississippi run by its former slaves.

The enslaved became paid workers.

Families were reunited.

Children were taught openly to read.

Profits were shared equally, and discipline was replaced by consent.

To outsiders, it looked like eccentric benevolence—some moral experiment by a guilty southern woman.

But inside Thornwood’s gates, it was revolution.

Ezekiel, officially “dead,” now lived as Joseph, a hired overseer from Virginia.

He coordinated the work and maintained the illusion.

Catherine handled the legal correspondence and the delicate dance of pretending to be a respectable white lady.

Together, they built a small, functioning democracy on stolen land and borrowed time.

IX. The Storm

Their peace couldn’t last.

Rumors spread—educated slaves, odd paperwork, a master’s daughter with radical ideas.

First came the creditors, then the sheriff.

Each investigation pushed them closer to exposure.

When Sheriff Cobb arrived demanding to interrogate the “negroes,” Catherine stood her ground.

“These are free workers under my supervision,” she said.

Cobb sneered. “We’ll see about that.”

The interviews yielded nothing. The community had rehearsed their answers.

Ezekiel’s grave—a fake filled with stones—convinced the sheriff he was truly dead.

But Cobb’s suspicion didn’t fade. It curdled.

X. Forbidden Love

By late summer 1854, the rebellion had evolved into something neither of them expected.

Love.

Catherine and Ezekiel had shared danger, guilt, and survival.

Now they shared something deeper.

One stormy night in August, lightning crashed outside as they worked in the study.

When Ezekiel rose to leave, Catherine stopped him.

“You should stay. It’s too dangerous to ride out.”

He hesitated. “If we do this, there’s no going back.”

“I crossed that line when I killed my father.”

They kissed, and the line between master and slave, white and black, man and woman, dissolved into something forbidden and free.

In the antebellum South, that act was more dangerous than rebellion itself.

It was proof that the walls of race and power could fall—and that terrified those who depended on them.

XI. The Betrayal

In September, a runaway named Jacob arrived at Thornwood seeking refuge.

Catherine and Ezekiel took him in, knowing it was a crime under federal law.

Two weeks later, slave catchers came.

They found nothing—but they told Sheriff Cobb everything.

Then came the real betrayal.

A neighboring planter named Sutherland, infuriated by Thornwood’s success, had been spying.

One night he saw through the study window what Mississippi law called an abomination: Catherine and Ezekiel together.

Within days, Cobb had drafted federal warrants for fraud, harboring a fugitive, and—worst of all—miscegenation.

Punishment would be death.

XII. The Exodus

A sympathetic deputy rode to warn them.

“They’re coming in forty-eight hours. They know everything.”

Ezekiel gathered everyone.

“Stay, and they’ll hang us. Run, and maybe we live free.”

Thirty-five chose to run. Twelve stayed behind, too old or too afraid.

They destroyed every record, packed food, and forged new papers.

Then they made one final decision: Thornwood would burn.

At three in the morning, Catherine stood with a torch in her hand.

Her family’s home loomed before her, silent as a tomb.

“Burn it,” she said.

Flames devoured the mansion, the barns, the ledgers, the symbols of everything that had enslaved them.

By dawn, the plantation was gone—its name erased, its history smoldering.

To the authorities, it was a massacre.

To those who escaped, it was deliverance.

XIII. The Long Road to Mexico

The refugees scattered in small groups.

Some moved by night through Louisiana.

Some posed as freed laborers.

Some never made it out of Mississippi.

But thirty souls reached the Rio Grande in early 1855.

Ezekiel and Catherine crossed last, disguised as husband and wife.

To Mexico, they were just another couple fleeing the turmoil of the North.

They settled in Monclova, Coahuila.

There, they built a store, learned Spanish, and began to write.

For twenty-three years, they recorded everything—the rebellion, the love, the flight.

Their manuscript, The Thornwood Record, was part confession, part testimony, part declaration of humanity.

They called it, simply, The Truth.

XIV. Rediscovery

Ezekiel died in 1881, Catherine two years later.

Before her death, she buried their manuscript beneath an olive tree, sealed in oilcloth, with a note to her daughter:

“Tell this when the world is ready to hear it.”

It stayed buried for seventy years.

In 1947, their granddaughter, María Márquez de López, gave the map and key to Dr. Eleanor Winters of the University of Texas.

What Winters unearthed stunned historians:

Four hundred pages of precise handwriting describing one of the most sophisticated slave uprisings in American history.

She spent three years verifying it—matching signatures, deeds, and county gaps.

Everything aligned.

Even the missing entry in the 1857 census was real.

When Winters published her findings in 1951, the South erupted in fury.

Newspapers called it abolitionist propaganda.

Churches called it sinful fiction.

But the documents were undeniable.

For seven months in 1854, a plantation in Mississippi had indeed become a commune of free Black people and one white woman who’d chosen them over her own blood.

XV. The Legacy

Today, a small historical marker stands off a rural road near Quitman, Mississippi.

It reads:

Thornwood Plantation (1840–1856): Site of a slave rebellion led by Ezekiel, an enslaved man, in conspiracy with Catherine Thornwood, daughter of the plantation owner.

Thirty-five people escaped to Mexico, never to be recaptured.

Few locals mention it. Many still want the marker removed.

But it stands—a sliver of truth in soil that once grew cotton and silence.

XVI. What Remains

Historians still debate what Thornwood means.

Was Ezekiel a hero or a murderer?

Was Catherine a liberator or an accomplice?

Does love redeem violence—or only complicate it?

What’s certain is that for seven months in 1854, human beings long considered property lived, worked, and loved as equals on Mississippi soil.

It didn’t last. It couldn’t. But it happened.

And that possibility—that glimpse of what could have been—was enough to terrify a nation built on slavery.

Thornwood wasn’t erased because it failed.

It was erased because it succeeded.

XVII. The Final Question

If you stand on the site today, the land looks ordinary. Cotton still grows there. The wind carries the same humid heaviness it did 170 years ago.

But beneath the soil, fragments remain—charred wood, broken glass, and maybe, just maybe, traces of the people who refused to remain invisible.

Ezekiel and Catherine’s manuscript lies preserved in a climate-controlled vault at the University of Texas.

Scholars read its pages with gloved hands, tracing the same letters Ezekiel once carved in dirt for his students: A for apple. B for bondage. C for courage.

He had taught them that knowledge was the first freedom.

And he was right.

The Thornwood Rebellion didn’t topple slavery, but it cracked its illusion of permanence.

It proved that the enslaved could plan, that a white woman could renounce her privilege, and that love—terrible, impossible love—could ignite revolution.

And maybe that’s the reason the record survived: because some truths refuse to stay buried.

XVIII. Epilogue: The Lesson

Every generation discovers its own Thornwoods—stories buried because they make the powerful uncomfortable.

We call them myths, exaggerations, legends.

But sometimes they’re just history written in the wrong handwriting.

Ezekiel’s story is not only about rebellion; it’s about possibility.

It asks the same question we still wrestle with:

What happens when people who have nothing left to lose decide to rewrite the world?

In that question lies the reason Thornwood matters—because it reminds us that even in the darkest systems, someone is always whispering letters in the dirt, spelling the word freedom.

News

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!!

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!! On…

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!!

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!! Aaliyah…

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!!

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!! 23 St.Paul Street….

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!!

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!! Bumpy…

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!…

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!!

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!! From a young…

End of content

No more pages to load