𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 charge for groom who 𝐤𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 stepfather at wedding; sheriff says it’s self defense | WSB-TV | HO

Another line, another voice, warning and blunt: “You better be right if you’re going to kill someone.”

And then a father’s grief, raw enough to make the studio feel too small. “Justice will prevail for my son’s—” the sentence caught, a word swallowed by loss.

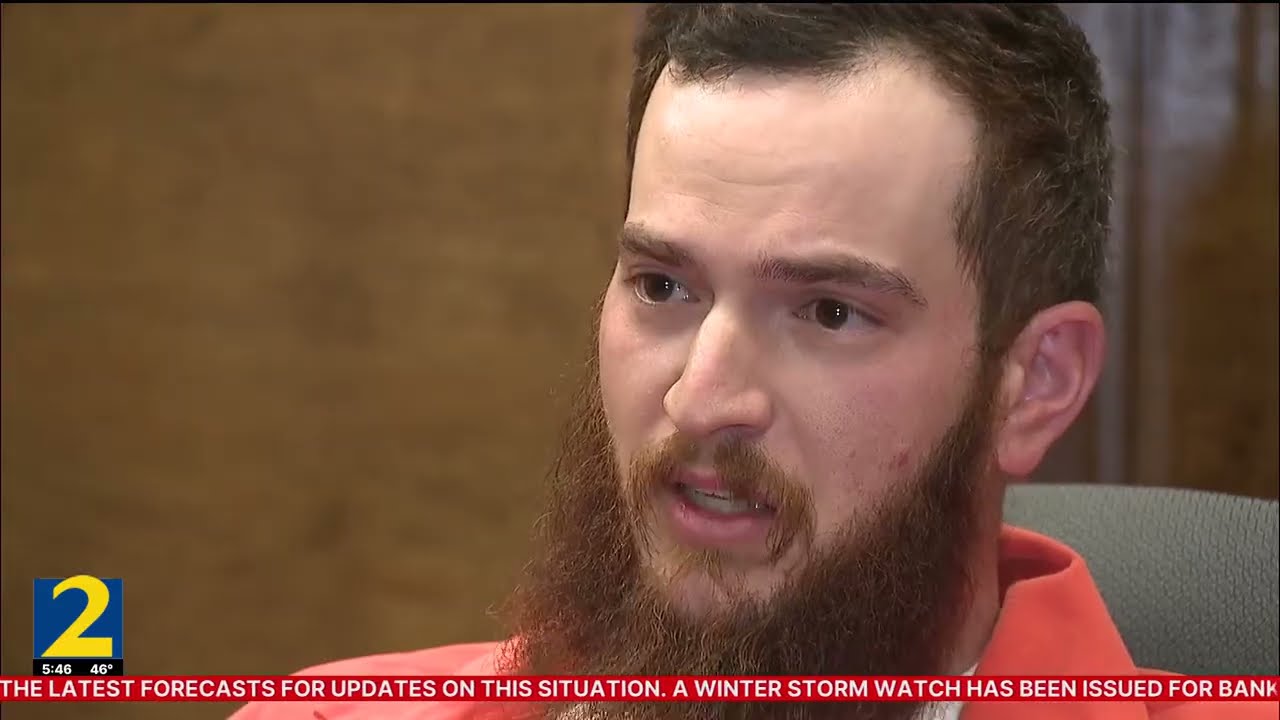

A bride and groom had stood smiling in July 2024—Kayla and Aaron White—posed for photos, rings on, hands linked, family gathered close the way families do when they want to believe closeness keeps trouble out. Hours later, it was undisputed that the groom shot and killed a man.

The question wasn’t whether a shot was fired. The question was what the law would call it when it happened—and who would carry the weight of that label.

Sheriff Gary Long wasn’t arguing the timeline. He wasn’t denying a death. He was arguing the word crime.

“I don’t think anyone should have to second-guess defending themselves,” he said. His tone wasn’t angry; it was disappointed, like a teacher watching a student abandon what they’d been taught. “But I do dispute that new husband Aaron White committed felony murder.” He leaned forward slightly, as if the camera could hear sincerity better up close. “There’s an innocent man sitting in my jail.”

Kayla White, the bride, spoke next, and the fact she could speak at all felt like its own kind of courage. The homicide victim, she said, was her stepfather—Jason Mahan, forty-four. “I liked him a lot,” she admitted, a sentence that carried complicated love in it, the kind families don’t put on bumper stickers. But she stood by her husband anyway. “I just have to have faith,” she said softly. “The truth will come out eventually.”

Mark Winnie’s report tightened the lens to the hinge point in the night—when celebration turned into confrontation. Both District Attorney Jonathan Adams and Sheriff Long agreed on the spark: after the wedding, the bride told a relative—apparently intoxicated, apparently behaving inappropriately—to leave. There was a tussle. Aaron got involved.

A clip played: a voice in the background, urgent and trying to be reasonable. “Time to separate them. This ain’t right.”

Jason Mahan, upset over the tussle and whatever it meant for family respect, showed up and punched Aaron White in the face. Aaron described it plainly, like it still surprised him. “Knocked me to the ground.”

Minutes later, Mahan returned, along with the relative who had tussled with the bride. The relative fired a gun. Witnesses differed on timing—on when a bullet struck Aaron White’s hand, on the sequence of steps, on exactly who moved first. But the story converged on one point: Jason Mahan chased Aaron White, and Aaron made it to his truck.

“I was able to draw my weapon,” Aaron said in the interview.

“And did what?” came the question.

“Defended myself and everybody else.”

“You shot him?”

“Yes.”

The law lives in that space between “I had to” and “You didn’t.” It lives in whether a fear is reasonable and whether a response is lawful. It lives in who gets believed and when.

Sheriff Long said his office investigated and then called the Georgia Bureau of Investigation for an independent look, as if he knew the case would need more than one set of eyes to be trusted. District Attorney Adams said a 2025 grand jury found self-defense and declined to charge White for the homicide. Others were indicted for aggravated assault, he said—then he dismissed those charges.

And then, this month, the turn that made the story ignite again: Adams presented the case to a second grand jury. This time, the jury indicted Aaron White for felony murder and aggravated assault.

A second look can be justice or politics depending on where you’re standing—and sometimes the only difference is what year it is.

Mark Winnie framed it the way prosecutors often frame hard cases: not as a question of feelings, but of options. District Attorney Adams said the key issue was whether White should have responded to Mahan with a gun or with his hands. “It’s a question for a jury,” Adams said, “to determine whether or not the defendant had a reasonable belief of receiving serious bodily injury.”

Sheriff Long didn’t dispute that the standard existed. He disputed how it was being applied—and he said it out loud, in a way that made other sheriffs in other counties sit a little straighter.

He spoke about something most people never connect to felony murder indictments: gun safety classes. The sheriff said the DA’s decision flew in the face of what he’d taught citizens about protecting themselves, classes in which the DA had joined him before.

“People will be hesitant to defend themselves,” Long said, the words landing with weight in a state where a lot of folks have grown up with firearms the way they grew up with toolboxes. “For the mere fact of coming to jail for murder.”

In the same report, grief held its own microphone. Dan Mahan, Jason’s father, stood with the posture of a man who has learned how to stand through pain because sitting down feels like collapse. “No parent should bury their child ever,” he said. He didn’t demand blood on camera. He demanded process. “We’re just going to let the state of Georgia and the district attorney’s office and all of the law enforcement settle this thing.”

Mark Winnie asked the question people ask when they don’t know what else to ask. “What gives you the wherewithal to get through this?”

“God,” Dan Mahan said. “Friends, family, community.”

Behind the words was a quiet understanding that in courtrooms, faith doesn’t replace evidence—but it’s sometimes the only thing that keeps a family from breaking apart while the evidence is argued over.

The anchors returned to the split that made the report feel less like crime coverage and more like a civic fracture. Mark said that since the on-camera interview, Aaron White had been released on bond. Defense attorney Brett Dunn said there were areas he didn’t want White to speak about because of the pending prosecution. Dunn also said he believed an election played a role in the case.

The studio promised more at 6.

But the story had already done what stories like this always do in small counties and big states: it moved from the news into diners, into group texts, into church parking lots, into late-night arguments on porches where people used to talk about football.

On one side, people said: You can’t punish a man for surviving a chaotic night where bullets were already in the air.

On the other, people said: A wedding doesn’t grant immunity. A punch doesn’t automatically justify a gun. And if you’re wrong, someone doesn’t go home.

Even if everyone agreed on the same set of facts, they didn’t agree on what those facts meant. And in American law, meaning is the battlefield.

In the evidence photos, the scene looked like a blur of human decisions stacked too close together: an argument, a scuffle, a shove, a blow, a chase, a truck door, a hand reaching where it had reached a thousand times in practice and a thousand times in imagination. Somewhere in there, a line got crossed—or it didn’t. The state would have to draw that line with testimony and timelines, not with gut feelings.

Sheriff Long’s voice replayed, stubborn and paternal: “There’s an innocent man sitting in my jail.”

District Attorney Adams’ position replayed, colder but no less certain: the issue wasn’t self-defense as a concept. It was lawful use of deadly force under the circumstances—whether the belief of serious bodily injury was reasonable, whether the response was necessary, whether another option existed.

And then Aaron White’s own voice replayed, stripped of legal language and left with only fear: “Life or death… I’ve got to get to my weapon.”

A wedding is supposed to be a beginning, and instead it became a case file with two grand juries and one county split down the middle.

Mark Winnie’s report, for all its calm delivery, made one thing unavoidable: the system wasn’t speaking with one voice. The sheriff said self-defense was clear. The district attorney said the law required a jury to decide. A grand jury once declined to charge; another grand jury later did. The groom said he feared for his life. The victim’s father said justice would prevail. The bride said she had faith.

And in a place like Butts County, people didn’t just watch that on TV. They took it personally—because it asked a question that sits under a lot of American life, under a lot of American fear.

When you’re cornered, what are you allowed to do—and what will it cost you afterward?

Months from now, jurors may sit in a box and listen to witnesses disagree about seconds. They may hear about who fired first, about when a hand was hit, about who chased whom, about how close danger felt in the dark after a wedding. They may be asked to imagine their own bodies in someone else’s panic, to measure reasonableness with hearts that were not there.

But on the night the story hit the 5 p.m. news, the only certainty was that a man died, another man was charged, and a county sheriff had drawn a public line against his own district attorney for the first time in thirteen years.

The first thing you noticed in the footage wasn’t the courthouse steps or the yellow legal pad in the reporter’s hands—it was the little U.S. flag lapel pin on the groom’s suit, a cheap enamel rectangle catching studio glare like it was trying to look brave. On a night that was supposed to end with cake boxes and leftover champagne in plastic cups, it ended with sirens, statements, and a name entering the system. “New at 5,” the anchor said, voice steady the way TV teaches you to be steady, “a deadly shooting after a wedding. And now the groom has been charged with felony murder.” In Butts County, Georgia, where folks still wave from pickup beds and argue about church parking instead of headlines, the story landed like a dropped tray—loud, messy, and impossible to ignore. Channel 2 investigative reporter Mark Winnie sat under cool studio lights and said what made people sit up straighter: the sheriff and the district attorney weren’t aligned, and the split wasn’t quiet.

Mark looked into the lens, then toward the anchors. “Butts County Sheriff Gary Long says the felony murder charge against a groom for a shooting on his wedding night marks the first time since he became sheriff—thirteen years ago—that he has publicly disagreed with his district attorney.” Thirteen years wasn’t just a statistic; it was a way of saying, I don’t do this lightly. On screen, evidence photos appeared in quick succession—dozens of still frames from a night that started in formalwear and ended in chaos: a driveway lit by harsh headlights, a cluster of people frozen mid-motion, shadows and angles that made everything look both obvious and impossible to prove.

District Attorney Jonathan Adams said he’d done the right thing. Sheriff Long said, flatly, that an innocent man had been jailed. And then the admitted shooter’s voice cut through the studio package, not polished, not practiced, just urgent and tight. “I’m going—it’s a life-or-death situation,” Aaron White said. “I’ve got to get to my weapon.”

Someone asked the question people always ask because language doesn’t know what else to do. “Why did you shoot him?”

“Fear for my life,” Aaron answered.

Sheriff Long followed with a sentence that sounded like a verdict even before any jury sat down. “Clearest case of self-defense,” he said, “that I have personally seen in thirty years of law enforcement.”

Another voice—warning, blunt, almost parental—cut in: “You better be right if you’re going to kill someone.” Then a father’s grief, heavier than any argument about statutes: “No parent should bury their child ever.”

A wedding is supposed to be the start of something, but in this case it became the start of a fight over what the law calls reasonable.

A bride and groom—Kayla and Aaron White—had stood smiling after a July 2024 ceremony, posed for pictures, rings on, hands linked, family close the way families get close when they want to believe closeness keeps trouble out. Hours later, it was undisputed that the groom shot and killed a man: forty-four-year-old Jason Mahan, the bride’s stepfather. There was no controversy about whether a shot was fired; the controversy lived in the name prosecutors attached to it.

“I don’t think anyone should have to second-guess defending themselves,” Sheriff Gary Long said, and he didn’t say it like a slogan. He said it like a man who had taught that exact idea in community rooms with folding chairs. “But I do dispute that new husband Aaron White committed a crime, felony murder, as an indictment now alleges.” He leaned forward toward the camera, as if sincerity could close distance. “There’s an innocent man sitting in my jail.”

Kayla White spoke next, and the fact that she could speak at all felt like its own kind of endurance. She admitted something that didn’t fit neatly into either side’s talking points. “Jason was my stepdad,” she said. “I liked him a lot.” The word liked sounded too small for the complicated history families carry, but it was what she could offer without betraying anyone. Still, she stood by her husband. “I just have to have faith,” she said quietly. “The truth will come out eventually.”

Both Sheriff Long and DA Adams agreed on the spark that lit the rest of the night: after the wedding, the bride told a relative—apparently intoxicated, apparently behaving inappropriately—to leave. There was a tussle. Her husband got involved.

In a clip, a voice rose over the commotion, urgent and trying to be reasonable. “Time to separate them. This ain’t right.”

Then Jason Mahan appeared, perhaps upset about what the tussle meant—about respect, boundaries, family pride. He punched Aaron White in the face.

“Knocked me to the ground,” Aaron said.

Minutes later, Mahan and the same relative returned. The relative fired a gun. Witnesses differed on timing—on whether the gunshot that struck Aaron White’s hand happened earlier or later, on which movement came first, on whether the chase started before someone realized how serious the night had become. But the narrative converged on a point everyone seemed forced to agree with: Jason Mahan chased Aaron White, and Aaron White made it to his truck.

“I was able to draw my weapon,” Aaron said.

“And did what?” the question came.

“Defended myself and everybody else.”

“You shot him?”

“Yes.”

In the law, “self-defense” isn’t a feeling; it’s a threshold, and everyone argues about where that threshold sits.

The package explained how the case had already taken one full circuit through the justice system before the public ever saw the split. Sheriff Long said his office investigated and then called in the GBI—Georgia Bureau of Investigation—for an independent look, the kind of move that signals both caution and a desire to be believed later. DA Adams said a 2025 grand jury found self-defense and declined to charge Aaron White for homicide. Other people in the incident were indicted for aggravated assault, the report said, but the DA dismissed those charges.

Then came the pivot that made the case flare back to life: this month, DA Adams presented the case to a second grand jury. This time, the second grand jury indicted Aaron White for felony murder and aggravated assault.

Two grand juries can look at the same night and come back with two different answers, and that’s not a glitch—it’s the system showing you its seams.

Mark Winnie framed the disagreement the way prosecutors tend to frame hard cases: not as a question of emotion, but of options. DA Adams said the key issue was whether White should have responded to Mahan with a gun or with his hands. “It’s a question for a jury,” Adams said, “to determine whether or not the defendant had a reasonable belief of receiving serious bodily injury.” It sounded clinical, but it was also the point where ordinary people listening at home started arguing with their TVs. Because the question isn’t just what happened. The question is what any of us would be allowed to do if the world turned chaotic in a parking lot after a wedding.

Sheriff Long didn’t deny the legal standard existed. He said the decision to charge flew in the face of what he’d taught citizens for years. He talked about gun safety classes, the kind held in community buildings where people come with questions they don’t ask in public. And he pointed out that the district attorney had joined him in those classes before.

“People will be hesitant to defend themselves,” Long said. “For the mere fact of coming to jail for murder.”

In another clip, Kayla’s voice sounded smaller than her dress probably had looked. “I just have to have faith,” she repeated, as if repetition could hold the world together.

And then the victim’s father, Dan Mahan, spoke with the careful steadiness of someone who has learned to stand through grief because sitting down feels like collapse. “No parent should bury their child ever,” he said. He didn’t demand a particular outcome on camera. He demanded process. “We’re just going to let the state of Georgia and the district attorney’s office and all of the law enforcement settle this thing.”

Mark asked the question reporters ask when they don’t know what else to ask. “What gives you the wherewithal to get through this?”

“God,” Dan Mahan said. “Friends, family, community.”

Behind that answer was the unspoken truth: the courtroom would be a different kind of church, one where belief didn’t substitute for evidence, but where everyone still prayed for something—vindication, accountability, relief.

Back in the studio, Mark Winnie added one more update like a match thrown onto dry grass. Since the interview, Aaron White had been released on bond. Defense attorney Brett Dunn said there were areas he did not want White to speak about because of pending prosecution. Dunn also said he believed an election had played a role in the case.

And just like that, the story stopped being only about a night and became about a season.

When a case touches weddings, family, and fear all at once, it doesn’t stay inside a courtroom file. It moves into diners, group chats, church parking lots, and late-night porch conversations where people talk like they’re arguing about someone else but they’re really arguing about themselves. Some people said, A man shouldn’t be punished for surviving a night where shots were already in the air. Others said, A wedding doesn’t grant immunity, and a punch doesn’t automatically justify a gun. And nearly everyone—no matter which side they leaned toward—agreed on the one sentence nobody could make sound less terrible: one man didn’t come home.

Kesha-like instincts weren’t required to see what the case would hinge on; you just had to listen to how the adults around it spoke. Sheriff Long spoke like a man protecting a principle he’d sold to the public for years: don’t hesitate if your life is in danger. DA Adams spoke like a man guarding a different principle: if lethal force becomes the default answer, the law stops meaning anything.

Between those principles sat a jury box that didn’t exist yet, waiting like an empty chair at a family table.

If you freeze the story at the moment Aaron reached his truck, everything looks like motion without meaning: someone running, someone chasing, someone holding a wounded hand, someone yelling, someone firing somewhere else. But prosecutors and defense attorneys don’t argue about motion; they argue about choices. They argue about whether Aaron had a moment to disengage, whether the chase was still a threat at the truck, whether he reasonably believed he faced serious bodily harm, and whether using lethal force was lawful under Georgia law.

DA Adams’ position reduced it to a single line of inquiry: gun or hands. Sheriff Long’s position was different: when bullets are already part of the night and a man is being pursued, you don’t ask him to solve it like a wrestling match.

And Kayla—caught between husband and stepfather, between vows and blood ties—kept saying what she had. “The truth will come out,” she said, and it sounded less like optimism and more like survival.

The evidence photos didn’t show feelings. They showed angles. Distances. Who stood where. What the lighting looked like. What the ground looked like. What a truck door looked like when it was open. Somewhere in those dozens of images, a prosecutor would point and say, Here is the decision point. Somewhere else, a defense attorney would point and say, Here is the threat.

Mark Winnie said Jonathan Adams believed he did the right thing. The sheriff said it was the clearest self-defense case he’d seen in thirty years. And the anchors, sitting in their suits, reminded everyone there would be more at 6.

But the truth was, for the people living in the county, 6 p.m. wasn’t the next chapter. The next chapter was the day after, when you had to see your neighbor in line at the gas station and pretend the story wasn’t sitting between you like a third person.

A wedding night doesn’t usually come with a bond hearing, but this one did. Somewhere behind the scenes, paperwork moved the way paperwork always moves, indifferent to the fact it carried a man’s name and another man’s death. Aaron White’s defense attorney said he didn’t want his client discussing certain parts publicly because of the pending prosecution. That caution was as much strategy as it was protection. Because in a case like this, every sentence becomes an exhibit later.

“Life or death,” Aaron had said in the interview audio. “I’ve got to get to my weapon.” It wasn’t a legal argument; it was a confession of what his brain believed in that moment. In court, that belief would be held up to the light and measured against “reasonable.” Reasonable is the word the law uses when it wants to sound objective about a thing that is almost never objective in the moment.

Sheriff Long’s “thirteen years” became its own kind of evidence—not legal evidence, but credibility evidence. Viewers heard it and thought, He wouldn’t risk this unless he meant it. Others heard it and thought, That’s exactly what politicians say when they want you to stop asking questions.

The defense attorney’s suggestion that an election played a role turned the volume up further. People who never learned the difference between a grand jury and a trial suddenly had opinions about grand juries. People who didn’t know what felony murder meant were suddenly debating it as if the definition could change depending on who said it first.

Felony murder is a phrase that hits the ear like a sledgehammer because it sounds like intent even when the statute is more complicated than intent. It’s the kind of charge that makes someone’s mother cry in a kitchen even if she doesn’t fully understand the legal mechanics. It’s also the kind of charge that makes a victim’s family feel, for a moment, like the system is finally taking the death seriously.

That’s what made the split so combustible. Both sides could claim they were protecting the public.

Sheriff Long, looking straight into the camera, said his fear was that people would become hesitant to defend themselves, afraid that doing so would land them in jail for murder. DA Adams, by pushing the case to a second grand jury, signaled his own fear: that the public might normalize lethal responses in chaotic situations, and that the only way to prevent that was to let a jury draw a line.

And in the middle of those fears, Kayla tried to stand upright. She had married Aaron hours before, and now she was learning what it meant to be a wife in a story the world had already named.

It’s easy to treat cases like this as puzzles with a clean answer. But this one wasn’t a puzzle; it was a collision of roles. A groom. A stepfather. A bride. A relative told to leave. A sheriff. A district attorney. A father burying a son. Each person carried a title that came with expectations, and those expectations fought each other.

The sheriff and the DA agreed that things “went south” after the wedding when Kayla told a relative to leave. That agreement mattered more than it seemed, because it established a shared starting point. But after that, the story fractured into two interpretations: one where Aaron was being hunted in a chaotic scene and did what he had to do, and another where lethal force was not the only available response.

Witnesses differed on the sequence around the gunshot that struck Aaron’s hand. That difference matters in court the way inches matter in a crash report. If Aaron was injured before he ran, if the threat escalated before the truck, if the chase involved an imminent danger of serious bodily injury, that supports one narrative. If the injury timing is uncertain and the threat at the truck is arguable, that supports another.

And the truth that nobody liked saying out loud was that even honest witnesses can remember the same night differently when adrenaline and fear are part of the scene. Memory can be faithful and still be wrong.

In the studio package, Mark Winnie let the voices do the work. Aaron’s voice was strained but direct. Sheriff Long’s voice was confident, almost protective. DA Adams’ voice was measured, legal, careful to place the decision where he said it belonged: with a jury.

“Reasonable belief,” Adams said, and that phrase sounded like a judge’s gavel even without a judge in frame.

In another part of the report, the bride’s face looked like someone who hadn’t slept since the wedding. She said she liked her stepfather, but she stood with her husband anyway. That admission didn’t satisfy anyone completely. Supporters of Aaron wanted her loyalty to be simple and absolute. Supporters of Jason Mahan wanted her grief to be louder. But real people rarely behave the way the public demands. Real people try to survive.

And then there was Dan Mahan, the father, who refused to perform anger for the camera. He said he would let the state and the DA’s office and law enforcement settle it. He spoke about God, friends, family, community—the scaffolding people use when they’re forced to stand in a life that no longer feels like theirs.

No parent should bury their child. No bride should have to talk about her wedding night in the language of indictments. No groom should have to learn the weight of “felony murder” as a phrase attached to his name. But the story didn’t care what should happen.

It only cared what did.

If the sheriff’s public disagreement was unprecedented in thirteen years, that meant something else too: the pressure behind the scenes must have been intense enough to push a career officer into the light. Sheriffs don’t pick fights with DAs unless they’re sure—or unless they’re desperate—or unless they believe silence would be worse. When Long said he’d taught citizens in gun safety classes that they shouldn’t second-guess defending themselves, he wasn’t just defending Aaron White. He was defending his own message to the public. Because if the public began to believe that defending yourself could lead to a murder charge, they’d either hesitate when they shouldn’t—or decide the whole system was arbitrary.

And if the DA believed the “gun or hands” question belonged in front of a jury, he wasn’t just prosecuting a case. He was trying to establish, publicly, that lethal force is not automatically justified by fear. That fear has to meet the law’s standard.

The law, in that sense, was trying to do what it always tries to do: turn panic into a sequence of choices and call some of those choices legal and others not. The problem is that panic doesn’t arrive in a sequence. It arrives all at once.

Somewhere between the wedding venue and Aaron’s truck, between the punch and the chase, between the gunshot fired by someone else and the gunshot that ended Jason Mahan’s life, the night crossed into a category that would take months or years to untangle.

At 6 p.m., the station promised to air both sides of the election controversy. People would watch. People would argue. People would take screenshots of headlines and send them like weapons. But none of that would bring Jason back, and none of that would return Kayla’s wedding night to what it had been meant to be.

The only thing that would move the story forward now was court: motions, hearings, arguments, the slow churn that tells families to be patient while their lives remain on hold.

And somewhere in a file—among those dozens of evidence photos—there would be one image that, to a jury, would feel smaller than everything else and yet carry its own gravity: the groom in his suit, the little U.S. flag lapel pin still fixed to the fabric, a bright symbol sitting above a heart that insisted it was acting to survive.

First it had been just a detail you noticed on television. Then it became a marker of how the story was being framed: patriotism, protection, “defend yourself,” the simple story Americans like to tell about danger. And by the end of the report, it felt like something else entirely—an emblem of the country’s hardest argument with itself.

When you’re cornered, what are you allowed to do—and what will it cost you afterward?

In Butts County, the question didn’t stay abstract. It sat at kitchen tables. It sat in squad cars. It sat in the DA’s office. It sat with Kayla when she tried to sleep. It sat with Dan Mahan when the house went quiet and nobody called anymore.

Sheriff Long said an innocent man had been in his jail. Mark Winnie said Aaron White had since been released on bond. The defense attorney said he didn’t want his client discussing certain areas publicly. The DA said it was for a jury to decide.

A lot of people looking at this very closely, the anchor said, and it sounded like understatement wrapped in professionalism.

Outside the studio, outside the courthouse, outside the arguments, a wedding album existed somewhere with pictures of Kayla and Aaron smiling in July heat, unaware of how quickly joy can be rewritten into evidence. In those photos, the lapel pin probably looked like nothing at all—just a tiny flag, just a small nod to tradition.

Now it looked like a reminder: the symbols people wear are always simpler than the stories they end up living.

News

Wealthy Widow Had A Love Affair With A Prisoner — He Got Out & She Was Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 … | HO

Wealthy Widow Had A Love Affair With A Prisoner — He Got Out & She Was Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 … |…

Father Sh0t Daughter-in-law After Learning Of Her Secret 3-year 𝐋𝐞𝐬𝐛𝐢𝐚𝐧 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫 With His Wife | HO!!

Father Sh0t Daughter-in-law After Learning Of Her Secret 3-year 𝐋𝐞𝐬𝐛𝐢𝐚𝐧 𝐀𝐟𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫 With His Wife | HO!! A young woman lay…

West Virginia 2010 Cold Case Solved — Arrest Shocks Isolated Mountain Community | HO!!

West Virginia 2010 Cold Case Solved — Arrest Shocks Isolated Mountain Community | HO!! A little more than half an…

Miami Trans Says ”𝐍𝐨 𝐒£𝐱 𝐁𝐞𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐌𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐠𝐞”, On their Wedding Night, He Sh0t Her 14X After Disco.. | HO!!

Miami Trans Says ”𝐍𝐨 𝐒£𝐱 𝐁𝐞𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐌𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐠𝐞”, On their Wedding Night, He Sh0t Her 14X After Disco.. | HO!! Jasmine…

After Intimacy, He Laughed About Her 𝐒𝐦𝐞𝐥𝐥 — 30 Days Later, He Was Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 | HO!!

After Intimacy, He Laughed About Her 𝐒𝐦𝐞𝐥𝐥 — 30 Days Later, He Was Found 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐝 | HO!! People would later…

THE TEXAS 𝐁𝐋𝐎𝐎𝐃𝐁𝐀𝐓𝐇: The Mitchell Family Who 𝑺𝒍𝒂𝒖𝒈𝒉𝒕𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒅 21 Men Over a Stolen Flatbed | HO!!

THE TEXAS 𝐁𝐋𝐎𝐎𝐃𝐁𝐀𝐓𝐇: The Mitchell Family Who 𝑺𝒍𝒂𝒖𝒈𝒉𝒕𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒅 21 Men Over a Stolen Flatbed | HO!! Grady arrived within an…

End of content

No more pages to load