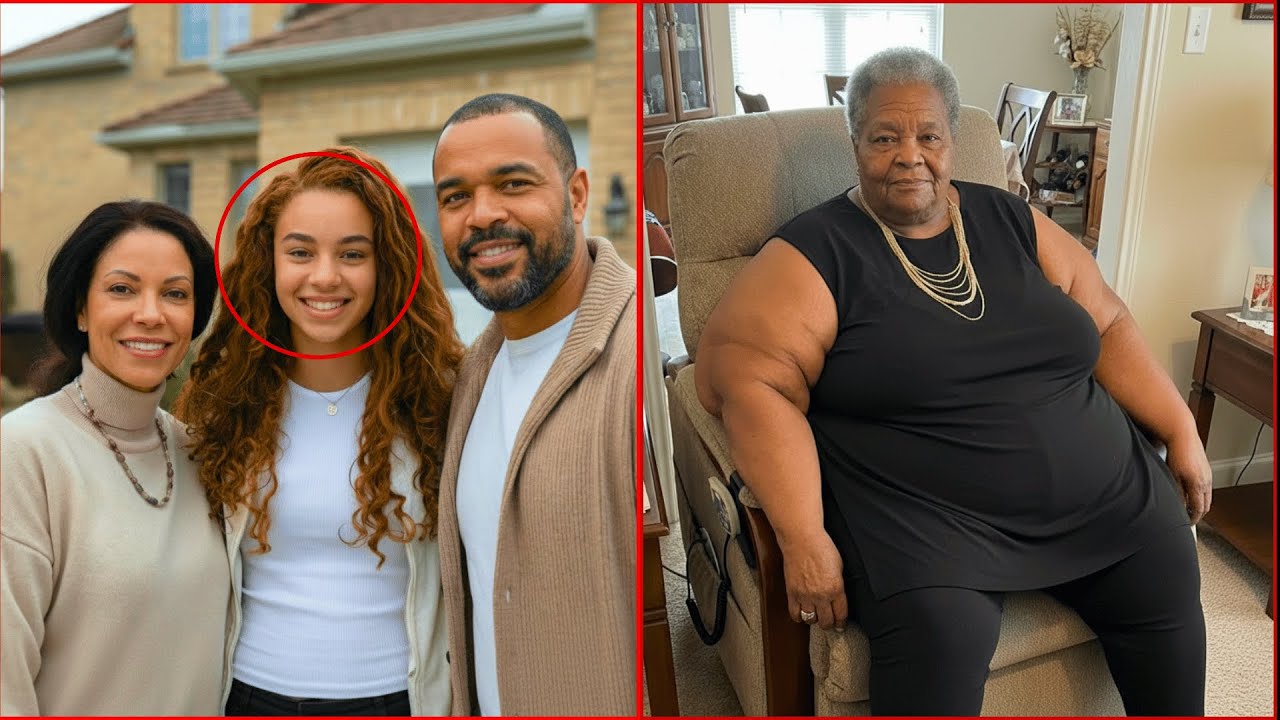

𝟏𝟎𝟎𝟎 𝐏𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝 𝐆𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐦𝐚 𝐏𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐬 𝐆𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐝𝐚𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐁𝐲 𝐋𝐚𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐎𝐧 𝐇𝐞𝐫 𝐔𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐥 𝐒𝐡𝐞 𝐃𝐢𝐞𝐬 | HO

Robert Miller, 41, worked in pharmaceutical sales.

It meant long hours, frequent travel, and a paycheck that kept the family comfortable in their modest three-bedroom home.

He’d grown up in a military family where orders weren’t questioned, and respect for authority was absolute.

His father had run their household like a boot camp, not abusive, but certainly not warm.

Robert had sworn he’d be different with his own children, more present, more understanding, more willing to talk through problems rather than simply impose solutions.

But intention and execution are different things.

Work consumed him.

The travel meant days away from home, missing dinners and school events, and the small moments that build parent child relationships.

When he was home, he was tired, stressed, not equipped to handle teenage drama.

So when Jennifer suggested sending Ashley to her mother’s house for a weekend of old school discipline, Robert didn’t push back.

He should have, but he was exhausted, frustrated, and out of ideas.

And then there was Ashley.

Ashley Marie Miller was 16 years old and caught in that impossible space between childhood and adulthood.

Not a child anymore, but not quite independent either.

She’d been an easy kid once, happy, compliant, eager to please.

But something shifted around age 14.

hormones, certainly the natural developmental push toward autonomy, but also something deeper.

A growing awareness that the rules her parents enforced didn’t always make sense, that obedience wasn’t the same as respect, that she had thoughts and feelings and opinions that deserved consideration.

She’d made the honor role through most of middle school and her freshman year of high school.

She’d played volleyball until conflicts with the coach, a woman whose authoritarian style reminded Ashley uncomfortably of her grandmother led her to quit.

She had two close friends from middle school, spent hours on Instagram and Tik Tok like every other teenager, and had recently started dating someone her parents disapproved of.

Tyler was 19, not dramatically older, but enough to trigger parental alarm.

He’d graduated high school the previous year, worked at an auto parts store, had vague plans about community college that he never quite acted on.

To Ashley, he represented freedom, someone who saw her as mature, interesting, worth listening to.

To her parents, he represented danger, a teenage pregnancy waiting to happen, a derailment of Ashley’s potential.

The arguments had escalated through February.

Ashley staying out past curfew.

Ashley being caught in lies about where she’d been.

Ashley’s grades slipping from B’s to D’s as she prioritized social life over school work.

Every conversation became a fight.

Every attempt at discipline met with eye rolling defiance or screaming matches that left everyone exhausted.

Teachers had noticed the change.

Ashley’s English teacher sent an email expressing concern about missing assignments and what seemed like depression or withdrawal.

The school counselor called suggesting family therapy.

But Jennifer and Robert interpreted these observations through their own lens.

Their daughter wasn’t struggling.

She was misbehaving.

She didn’t need therapy.

She needed consequences.

The family photos told the story.

Images from 5 years earlier showed a smiling girl with her parents at Disney World at Christmas morning unwrapping presents at a backyard birthday party surrounded by friends.

Recent photos showed something different.

Ashley’s smiles had become forced.

Her posture in family pictures was closed off, arms crossed, standing slightly apart from her parents.

The light in her eyes had dimmed.

On March 12th, 2 days before everything fell apart, Ashley came home 2 hours past curfew.

Robert had been watching through the window.

He saw Tyler’s car pull into the driveway.

Saw his daughter lean across the console for a kiss that lasted too long.

saw her adjust her clothes as she got out of the car.

That image, his 16-year-old daughter kissing a 19-year-old man in their driveway, ignited something in Robert.

Fear, anger, helplessness, all mixed together.

The confrontation was immediate and loud.

Robert told Tyler to never come back.

Ashley ran to her room, slammed the door hard enough to rattle the frame.

Jennifer stood in the kitchen listening to her daughter sobb through the walls and felt her own frustration reaching a breaking point.

That night, after Ashley had cried herself to sleep, Jennifer and Robert sat at the kitchen table and had the conversation that would change everything.

They were out of options.

Traditional punishment wasn’t working.

Taking away privileges just made Ashley angrier.

Grounding led to more sneaking out.

Trying to talk resulted in accusations that they didn’t understand, didn’t listen, didn’t care.

Jennifer brought up her mother.

Vera Thompson had raised her with strict old-fashioned discipline.

And while those methods had been harsh, Jennifer had survived, had become a functional adult.

Maybe Ashley needed that same wakeup call.

A weekend with Grandma Vera.

No phone, no friends, no boyfriend, just structure, rules, and the kind of non-nonsense authority figure who wouldn’t tolerate teenage rebellion.

Robert hesitated.

He’d always found Vera intimidating.

There was something cold about her, something that made him uncomfortable.

But he trusted his wife’s judgment, and honestly, he was desperate.

The image of Ashley in that car wouldn’t leave his mind.

He agreed.

It was decided.

They would drop Ashley off at Vera’s house on Friday afternoon.

She’d stay the weekend, come home Sunday evening, hopefully with a new attitude and renewed respect for her parents’ authority.

Before we continue into the details of what happened to Ashley Miller, I want to ask something of you.

If you believe stories like this matter, if you think awareness can prevent tragedy, please take a moment to like this video, subscribe to our channel, and share this with someone who needs to hear it.

The more people who understand how discipline can cross into danger, the more children we can protect.

Now, let’s continue with Ashley’s story.

Vera Thompson lived alone in a small ranchstyle house at the end of Oakwood Drive.

The house had been home for 30 years, purchased when her husband Harold was still alive, and she still had mobility.

Now at 72 years old, and weighing nearly 1,000 lb, Vera’s world had shrunk to the confines of her living room, kitchen, and downstairs bedroom.

She spent her days in a reinforced recliner positioned in front of the television.

The chair had cost $3,000, specially ordered to accommodate her size.

It dominated the small living room surrounded by the detritus of her existence.

Fast food rappers, medication bottles, religious magazines, remote controls.

A walker stood beside the chair, equipped with extra support bars to bear her weight on the rare occasions she moved from room to room.

Vera had worked as a cafeteria worker at the local elementary school for 20 years before her weight made employment impossible.

She’d gone on disability in 1999 and hadn’t held a job since.

Her days followed a rigid routine.

Wake at 6, watch morning news, eat breakfast, watch judge shows and religious programming, eat lunch, watch more television, eat dinner, watch evening news, sleep.

She left the house only for necessary medical appointments, transported by medical van because she couldn’t fit in a regular vehicle.

Her isolation was both circumstantial and chosen.

circumstantial because mobility limitations made social engagement difficult.

Chosen because Vera had little patience for people who didn’t share her worldview.

She’d stopped attending church regularly 15 years earlier after a new pastor started preaching messages she considered too soft, too focused on grace instead of consequences.

She’d stopped inviting neighbors over because their children misbehaved and their parenting was too permissive.

She’d stopped participating in community events because modern society had abandoned the values she held dear.

The only regular human contact came from Jennifer, who visited weekly to bring groceries and handle errands Vera couldn’t manage herself.

A home health aid came twice a week to assist with bathing, a humiliating necessity Vera endured with barely contained rage.

Otherwise, she was alone with her television, her religious materials, and her increasingly rigid beliefs about how the world should work.

Vera had been born in rural Georgia in 1947, the third of five children in a family that barely scraped by.

Her father worked as a sharecropper.

Her mother took in laundry.

They lived in a two- room house without electricity or running water.

Resources were scarce.

Patience was scarcer.

Children in that household learned quickly that obedience was survival.

Question your parents, earn a beating.

Talk back, go hungry, cause trouble, face consequences that left marks.

Vera internalized those lessons.

She learned to be invisible, to anticipate her father’s moods, to avoid triggering his anger.

She learned that love looked like control, that caring parents were strict parents, that the absence of physical punishment meant the absence of proper guidance.

By the time she left home at 18, pregnant, forced into marriage with Harold Thompson, those beliefs were bedrock.

She raised Jennifer the way she’d been raised, with an iron fist wrapped in biblical justification.

Spare the rod.

Spoil the child.

Wasn’t just a proverb to Vera.

It was a commandment.

Jennifer learned early not to cry when disciplined.

Learned to say yes ma’am with the proper tone.

learned that defiance, even mild, came with swift and painful consequences.

Harold had been a quiet man, conflict averse, content to let Vera run the household.

He worked at a factory, brought home his paycheck, and stayed out of her way.

When he died of a heart attack in 1989 at age 43, Vera felt loss, but also relief.

Now there was no one to question her methods, to suggest she might be too harsh, to interfere with her parenting philosophy.

After Harold’s death, Vera’s weight began climbing, grief eating certainly, but also the weight of absolute control.

With no job requiring physical presence, no husband requiring attention, no social obligations demanding engagement, Vera retreated into herself.

Food became comfort.

Television became companionship and her beliefs about discipline, authority, and the proper ordering of family relationships calcified in the absence of any contrary input.

By the time Jennifer married Robert and had Ashley, Vera weighed over 400 lb.

By the time Ashley was 10, Vera had crossed 700.

By 2019, she was approaching 1,000, completely homebound, dependent on others for basic needs, but maintaining absolute conviction in her own righteousness.

Jennifer’s memories of childhood were complicated.

She remembered fear, walking on eggshells, never quite knowing what would trigger her mother’s anger.

She remembered pain, punishments that left bruises, sometimes for days.

She remembered the isolation, not being allowed to have friends over, not being permitted to participate in activities that might interfere with chores or homework.

But she also remembered surviving, making it to adulthood, becoming functional.

And somewhere along the way, Jennifer had convinced herself that the harsh discipline had been necessary.

That without it, she might have gone astray.

That her mother’s methods, while unpleasant, had worked.

What Jennifer didn’t remember or chose not to were the moments that revealed the truth.

The neighbor who’d seen bruises and looked away.

The teacher who’d noticed Jennifer’s fear of authority figures and said nothing.

The church member who’d witnessed Vera dragging a crying toddler out of Sunday service by her ear and been too uncomfortable to intervene.

These moments had been filed away, minimized, recontextualized as normal for that generation.

So when Jennifer called her mother on March 13th to explain Ashley’s behavior problems and ask for help, Vera saw opportunity, a chance to prove her method still worked.

A chance to demonstrate that modern parents were too soft and children needed old school correction.

A chance to reassert her authority over a younger generation that had forgotten how to properly respect their elders.

“Send her to me,” Vera had said, voice firm with certainty.

“I’ll straighten her out one weekend, and she’ll learn what respect looks like.” Jennifer heard confidence in her mother’s voice.

Robert heard something he couldn’t quite name, something that made him uneasy in a way he couldn’t articulate.

Ashley, when told she was spending the weekend at her grandmother’s house, heard a prison sentence.

Friday, March 14th, 2019, arrived with the mundane ordinariness that often precedes tragedy.

Jennifer woke early, made coffee, went through the motions of a normal morning.

Ashley stayed in her room, avoiding her parents, radiating teenage resentment through the walls.

Robert left for work before the conflict could resume.

The plan was simple.

Jennifer would drive Ashley to Vera’s house around 2:00 in the afternoon.

Ashley would stay the weekend, Friday night through Sunday evening.

No phone access, no contact with friends, no Tyler, just time with her grandmother, following rules, learning respect.

Jennifer had convinced herself this was helping, giving Ashley the structured environment she needed, teaching her that actions have consequences.

Ashley packed her overnight bag with the enthusiasm of someone preparing for incarceration, a few changes of clothes, her phone charger, though her mother had already arranged to suspend her data access.

A book for English class she had no intention of reading.

Her journal where she’d been documenting the growing gulf between who her parents wanted her to be and who she actually was.

The final entry before leaving, written Thursday night.

They’re sending me to grandma’s like I’m some broken thing that needs fixing.

I just want them to listen to me, to see me, to understand I’m trying my best.

I’m not perfect, but I’m not a bad kid.

I’m just me.

Why isn’t that enough? The drive to Vera’s house took 20 minutes.

Jennifer drove.

Ashley sat in the back seat, arms crossed, staring out the window at suburban Florida, passing by.

strip malls, gas stations, fast food restaurants, churches, the ordinary landscape of American middle-class life.

Neither spoke.

What was there to say? Jennifer had made her decision.

Ashley had no choice but to comply.

Jennifer’s hands gripped the steering wheel tighter than necessary.

Part of her, a small part she tried to ignore, whispered doubt.

Was this really necessary? Couldn’t they try something else? Family therapy, like the school counselor suggested, more open communication, actually listening to what Ashley was trying to tell them.

But another part of her, louder and more insistent, drowned out those whispers.

Ashley needed discipline, structure, to understand that her behavior had consequences, that her parents’ rules existed for good reasons, that she couldn’t just do whatever she wanted without accountability.

Jennifer’s mother had taught her these lessons.

Now Vera would teach Ashley.

They pulled into the driveway at 1:53 p.m.

The house looked tired, peeling paint, overgrown landscaping, mailbox leaning at an awkward angle.

Through the front window, Jennifer could see the blue flicker of the television.

Always on, always Vera’s constant companion.

“Come on,” Jennifer said, voice trying for firmness, but landing closer to uncertainty.

“It’s just 2 days.” Ashley didn’t move immediately.

She sat in the back seat, staring at her grandmother’s house, feeling something she couldn’t name.

Dread, certainly anger at her parents for sending her here.

But underneath those surface emotions, something deeper.

A survival instinct trying to send up warning flares.

Don’t go in that house.

Something is wrong.

Get out.

Run.

But 16 years of conditioning overrode instinct.

Adults were in charge.

Parents made decisions.

Children obeyed.

Ashley grabbed her bag and got out of the car.

Vera was waiting at the door, a massive form supported by her walker.

She looked at Ashley with eyes that assessed and found wanting.

No warmth in that gaze.

No welcome, just a cold evaluation.

This is what I have to work with.

This is the disrespectful child who needs correction.

Get inside, Vera said.

Not hello, not how you are, just a command delivered with the expectation of immediate compliance.

Ashley walked past her grandmother into the house.

The smell hit her immediately.

Old food, medication, stale air from windows that hadn’t been opened in months.

The living room was dim despite it being early afternoon.

Curtains drawn.

The television volume was too loud.

Clutter everywhere.

It felt suffocating.

Jennifer followed with a grocery bag of snacks.

She’d brought crackers, fruit, granola bars, healthy options, as if proper nutrition could somehow mitigate what she was doing.

She set the bag on the kitchen counter and turned to her daughter.

“I love you,” Jennifer said, pulling Ashley into a hug that Ashley didn’t return.

“Be good.

Listen to your grandmother.

We’ll pick you up someday.” Ashley stood rigid in her mother’s embrace, not softening, not responding.

Part of her wanted to beg, “Please don’t leave me here.

Please take me home.

I’ll be better.

I promise.” But pride and teenage stubbornness kept her silent.

If her parents cared so little about her feelings that they’d ship her off to her grandmother’s house, then fine.

She wouldn’t give them the satisfaction of seeing her upset.

Jennifer released her daughter and walked back to her car.

She drove away without looking back because looking back might have meant seeing the expression on Ashley’s face.

Might have meant confronting the doubt gnawing at her conscience.

might have meant turning around and bringing her daughter home where she belonged.

Inside the house, Ashley stood in the entryway holding her overnight bag, staring at worn carpet and wondering how she’d survive 48 hours.

Her grandmother had already shuffled back to the recliner, the walker squeaking with each labored step.

“Put your bag in the back bedroom,” Vera called from her chair.

“Then come back here.

We need to discuss your behavior.” Ashley walked down the narrow hallway.

The back bedroom was small and dark, a twin bed with faded floral comforter, dresser missing one handle, single window overlooking the neighbor’s fence.

Prison cells probably felt more welcoming.

She dropped her bag on the floor and pulled out her phone.

No signal, or rather, her mother had restricted her data, of course.

From the living room, she could hear her grandmother’s television, some religious program about obedience and authority.

Ashley felt anger rising in her chest like acid.

This was so unfair.

All she’d done was try to have a normal teenage life, try to date someone, try to have friends, try to have some autonomy over her own existence.

And her parents response was to banish her to someone who thought it was still 1950.

She wanted to scream, wanted to cry.

Instead, she lay back on the bed and stared at the water stained ceiling, counting the hours until Sunday when this nightmare would end.

She had no idea she’d never make it to Sunday.

That within 24 hours she’d be dead on her grandmother’s living room floor.

That her parents decision to prioritize discipline over understanding would cost Ashley everything.

In the living room, Vera settled into her recliner and smiled.

This disrespectful child thought she could come here with an attitude, thought she could continue her defiant behavior.

Vera would teach her otherwise.

By the time this weekend ended, Ashley would understand proper respect, would know her place, would learn what real discipline looked like.

Vera had broken stronger wills than this teenagers.

She’d broken her own daughter’s will decades ago.

She’d do it again.

And if it required harsh methods, well, that’s what discipline was.

The Bible said, “Spare the rod, spoil the child.” Vera had no intention of sparing anything.

I’m curious, where are you watching this from? Drop your location in the comments below.

And if you’ve made it to this point in the story, leave a comment saying, “I am still here.” Let’s see who’s committed to hearing Ashley’s full story, no matter how difficult it becomes.

Ashley stood, smoothed her clothes, and walked back to face her grandmother.

Vera had positioned her recliner to face the television, but now she swiveled it slightly to look at Ashley standing before her.

The scrutiny was cold, clinical, like a scientist examining an unpleasant specimen.

“Your mother tells me you’ve been acting up,” Vera began.

talking back, running around with boys, disrespecting your parents, failing your classes.

Ashley kept her face neutral, but inside she was seething.

Failing classes, she had some D’s, yes, but also bees.

Running around.

She had a boyfriend.

One boyfriend.

That wasn’t running around.

But arguing would only make this worse.

I asked you a question.

Vera’s voice sharpened when Ashley didn’t immediately respond.

“I’m not failing all my classes,” Ashley said quietly.

“And I have a boyfriend.

That’s normal.” Ver’s expression hardened.

“Normal? A 16-year-old girl sneaking out to see a 19-year-old boy? That’s not normal, young lady.

That’s how girls end up pregnant and ruined.

That’s how families get destroyed.” “He’s not like that,” Ashley tried to explain.

We’re just dating.

My parents don’t even know him.

I don’t need to know him.

Vera cut her off.

I know his type.

And I know girls who think they’re grown before their time.

Your mother was the same way at your age.

Thought she knew everything.

I fixed that attitude real quick.

I’ll fix yours, too.

The promise in those words made Ashley’s skin crawl.

She wanted to ask what that meant, what fixing involved, but some instinct warned her not to.

Whatever her grandmother had done to her mother, whatever correction she had in mind, Ashley didn’t want to provoke it prematurely.

“Can I go back to my room?” Ashley asked, keeping her voice carefully respectful.

“No, sit down on that couch.

We’re not done talking.” Ashley sat.

The couch was worn and stained, positioned at an angle to the television.

Vera turned her attention back to the screen, but kept speaking, voice carrying over the religious programming.

You’re here because your parents have lost control of you.

They’ve been too soft, too permissive.

They’ve let you get away with behavior that should have been corrected years ago.

That’s what’s wrong with parents today.

They want to be friends with their children instead of authority figures.

They want their kids to like them instead of respect them.

Ashley bit her tongue.

She wanted to argue that respect and fear weren’t the same thing.

That her parents could be both authority figures and people who actually listened.

That maybe she wasn’t the problem.

Maybe the problem was adults who treated teenagers like criminals for wanting basic autonomy.

But she said nothing.

Just sat on that worn couch and let her grandmother’s lecture wash over her.

It went on for an hour.

Vera cycling through familiar conservative talking points about kids these days, about declining moral standards, about parents who refuse to discipline properly.

Ashley tuned most of it out, retreating into her own head the way she did during her parents’ lectures.

By 6:00, Vera finally called a break for dinner.

She’d made meatloaf earlier, heavy, overcooked, swimming in grease, green beans from a can, white bread.

the kind of meal that sat in your stomach like concrete.

Ashley forced it down, knowing that refusing food would only create conflict.

Vera prayed before the meal, a long prayer thanking God for discipline for parents who understood proper child rearing, for the opportunity to correct a weward granddaughter.

Ashley kept her eyes open during the prayer, a small act of rebellion that gave her a tiny sense of control.

After dinner, Vera sent Ashley to clean the kitchen, wash dishes, wipe counters, sweep the floor.

Ashley complied mechanically, moving through the tasks while her mind was elsewhere.

She thought about Tyler, about her friends, about her bedroom at home with its posters and familiar things.

She thought about school and how she’d actually been trying lately, despite what her parents thought.

She’d turned in the last three homework assignments.

She’d studied for her history test.

She was trying, but trying wasn’t enough.

Her parents wanted perfection, wanted complete obedience, wanted her to be someone she wasn’t.

And when she couldn’t meet those impossible standards, they’d shipped her off to someone even harsher, even less willing to see her as an actual person rather than a behavior problem to be fixed.

By 9:00, Ashley was exhausted.

The emotional weight of the day combined with the tension of being in her grandmother’s house had drained her completely.

She asked permission to go to her room.

Vera granted it with a warning.

Tomorrow morning we’re getting up at 7.

We’ll have breakfast and then you and I are going to have a long conversation about respect and consequences.

About what happens when children forget their place.

You’ll learn, Ashley.

One way or another, you’ll learn.

Ashley nodded and escaped to the back bedroom.

She changed into the clothes she’d slept in.

She hadn’t thought to pack actual pajamas and lay on the bed, staring at the ceiling.

Water stains formed patterns that looked like faces in the dim light from the hallway.

She counted them, trying to calm the anxiety thrumming through her body.

She thought about running.

She could walk out the front door right now.

Her grandmother couldn’t chase her.

Vera could barely walk with the walker.

Ashley could be blocks away before Vera even managed to get out of her chair.

She could call her parents to pick her up or call Tyler or just start walking and figure it out.

But that would mean confirming everything her parents believed about her, that she was defiant, uncontrollable, unwilling to accept consequences for her behavior.

It would mean proving them right.

And some part of Ashley, the part that still wanted her parents approval despite everything, couldn’t do that.

So she stayed, closed her eyes, and tried to sleep in that unfamiliar bed.

Tried not to think about tomorrow.

Tried to ignore the feeling that something was very wrong here.

If you’re enjoying this content and believe it serves an important purpose, please like this video, subscribe to our channel, and share it with your loved ones.

Share it not just for entertainment, but for protection.

Saturday morning came too early.

Ashley woke to her grandmother’s voice calling from the living room, sharp and impatient.

She fumbled for her phone to check the time, 7:30.

She’d overslept by half an hour.

Already, she’d broken a rule.

She dragged herself out of bed, splashed water on her face in the bathroom, and made her way to the kitchen.

Breakfast was waiting.

Cold eggs, burnt toast, the food sitting out so long it had congealed into something barely edible.

Ashley sat down and forced herself to eat under her grandmother’s watchful gaze.

“You’re late,” Vera said flatly.

“I told you 7:00.

I didn’t hear you,” Ashley mumbled through toast that tasted like charcoal.

“I’m sorry.” “Because you weren’t paying attention.” “That’s your problem, Ashley.

You don’t listen.

You don’t follow instructions.

You think rules don’t apply to you.” Ashley wanted to point out that she didn’t have an alarm clock, that she was in an unfamiliar house, that oversleeping by 30 minutes wasn’t a moral failing, but she swallowed the words along with the terrible eggs.

After breakfast, Vera ordered Ashley to clean the kitchen, every dish, every counter, sweep the floor, make it spotless.

Ashley complied, moving through the tasks while her grandmother watched television and provided running commentary on everything Ashley did wrong.

Dishes not rinsed properly.

Counter wiped but not dried.

Floor swept, but corners missed.

By 10:00, the kitchen passed inspection.

Ashley returned to the living room, hoping she could just sit quietly and let the day pass.

But Vera had other plans.

Sit down.

Vera gestured to the couch.

We’re going to talk about your attitude problem.

What followed was two hours of Vera dissecting everything wrong with Ashley.

Her clothes too tight, too revealing, designed to attract male attention.

Her friends, bad influences who encouraged rebellion.

Her boyfriend, a predator waiting to ruin her life.

Her social media, vanity and attention seeking.

Her grades, proof of laziness and disrespect for education.

Her parents, too soft, too permissive, too focused on being liked instead of being obeyed.

Ashley sat through it all, hands clenched in her lap, jaw tight with suppressed anger.

She tried not to respond, tried to let the words bounce off, but every criticism felt like a knife cutting away at her sense of self.

Everything about her was wrong according to her grandmother.

Her appearance, her interests, her personality, her choices.

Nothing she did was acceptable.

Nothing.

She was merited approval.

By noon, Ashley’s patience had worn through.

She was exhausted, frustrated, seething with resentment at being lectured like a criminal for being a normal teenager.

When Vera paused to catch her breath, Ashley spoke up.

Can I please just go back to my room? I understand.

I get it.

I’m terrible.

Can I have some space? The sarcasm was subtle, but present.

Vera caught it immediately.

That’s exactly what I’m talking about.

Ver’s voice went cold.

That tone, that attitude, that disrespect.

You think you’re clever? You think you can mock me in my own house? I’m not mocking you.

Ashley backpedled, realizing her mistake.

I just asked if I could go to my room.

No, we’re not finished.

Sit there and listen.

But Ashley was done listening.

Done sitting.

Done pretending this was helping anything.

She stood up.

I want to go to my room.

Sit down.

No.

The word hung in the air between them.

A line crossed.

A boundary violated.

In Vera’s worldview, children didn’t say no to adults.

didn’t refuse direct commands, didn’t assert autonomy over their own bodies and movements.

Ashley’s refusal was more than disobedience.

It was mutiny.

“If you walk away from me right now,” Vera said slowly, voice shaking with rage.

“You will regret it.” “Ashley turned toward the hallway.” She made it three steps before the full weight of what she’d said hit her.

She turned back, saw her grandmother’s face contorted with anger, and tried to deescalate.

I’m sorry.

I just need a break.

I’ll come back.

I just You think you can disrespect me because I can’t chase you? You think my size makes me powerless? Is that what you think? I didn’t say that, Ashley protested.

But it was too late.

Vera had found her justification.

Come here, Vera commanded.

Ashley’s feet moved before her brain could stop them.

Years of conditioning.

Adults give orders.

Children obey.

She walked back to stand in front of her grandmother’s recliner.

“Get on the floor,” Vera said.

“What?” “You heard me.

On your stomach on the floor right now.” Every instinct screamed at Ashley.

To refuse, to run, to do anything except comply.

But 16 years of being taught that obedience was survival overrode instinct.

She lowered herself to the floor, lying face down on the worn carpet, heart hammering so hard she could hear it in her ears.

She heard her grandmother shifting in the recliner, heard the creek of weight moving, heard the walker scraping across the floor, and then Vera was above her, lowering herself, using the walker for support, using the couch arm for balance, settling her weight onto Ashley’s back.

The pressure was immediate and crushing.

Ashley tried to inhale and couldn’t.

The weight compressed her chest against the floor, collapsing her lungs, making it impossible to draw a breath.

She tried to push up to create space between her body and the floor, but her arms couldn’t lift nearly 1,000 lb.

“Grandma,” she gasped, managing to turn her head to the side.

“Please can’t breathe.” This is what happens when children forget their place, Vera said calmly, adjusting her weight, settling in more firmly.

You’ll stay here until you learn respect.

Until you understand that when I give an order, you obey.

No arguments, no attitude, just obedience.

Ashley’s fingers clawed at the carpet, her legs kicked weakly, trying to find leverage.

She tried to speak, to beg, but there was no air.

Her vision was darkening at the edges.

Panic flooded her system.

Pure primal terror.

She was dying.

Her grandmother was killing her.

And there was nothing she could do to stop it.

She tried to scream but had no breath for sound.

Tried to push up but had no strength against the weight.

Tried to survive but had no options left.

Her struggles grew weaker.

The darkness at the edges of her vision spread inward and then consciousness slipped away.

The medical examiner would later determine that Ashley lost consciousness approximately 8 minutes after the compression began.

But Vera didn’t lift her weight.

She remained seated on her granddaughter’s back for another 27 minutes.

Whether she didn’t notice Ashley had stopped moving or didn’t care.

No one would ever know.

By the time Vera finally shifted her weight and used the walker to leverage herself into a standing position, Ashley was dead.

Had been dead for several minutes.

Her face was swollen and discolored.

Blood had leaked from her nose and mouth.

And on the back of her skull, where her head had been pressed against the floor with such force, there was an indentation, a depression where bone had fractured under sustained pressure.

Vera stared down at her granddaughter’s body.

Later, she would claim she thought Ashley was just unconscious, that this was part of the lesson, showing how serious disobedience could become.

But the stillness was undeniable, the unnatural color, the complete absence of the subtle movements that indicate life.

Vera shuffled back to her recliner and sat down heavily.

For 20 minutes, she just sat there staring at the television, some game show now, bright and cheerful, completely disconnected from the horror in the room, processing what had happened.

or perhaps not processing at all, just existing in the space between action and consequence in those strange minutes before reality fully penetrates.

At 1:43 p.m., she picked up her phone and dialed 911.

The call lasted 6 minutes.

The operator had to ask repeatedly for clarification, for explanation of what had happened, for Vera to check if Ashley was breathing.

She was being disrespectful.

Vera kept saying I was teaching her.

She just wouldn’t learn.

The operator tried to redirect.

Ma’am, is your granddaughter breathing? Can you check for a pulse? I can’t get down there, Vera said.

I can’t move her.

She’s just lying there.

By the time paramedics arrived at 1:47 p.m., Ashley Miller had been dead for approximately 30 minutes.

There was nothing they could do except document the scene and call the medical examiner, call the police, start the process of investigating a death that should never have happened.

Ashley died at 1:20 p.m.

on March 15th, 2019.

She was 16 years, 4 months, and 11 days old.

She died because her parents prioritized obedience over understanding, because her grandmother valued authority over life.

because a chain of decisions, each one individually comprehensible, combined into something unspeakably tragic.

She died begging for mercy that never came.

And that fact would haunt everyone who learned about her death for years to come.

Deputy Michael Rodriguez arrived at 1247 Oakwood Drive at 1:47 p.m.

The 911 call had been strange, cryptic, lacking the urgency typically present when someone reports an unresponsive juvenile.

He approached the small ranch house with caution, noting the overgrown yard, the peeling paint, the general air of neglect.

The front door was unlocked.

He entered, calling out his identification.

Sheriff’s department.

Anyone home? The smell hit him first.

Stale air, old food, something medicinal and unpleasant.

Then he saw the living room.

An elderly woman in a recliner watching television as if nothing was wrong.

and on the floor near the couch, a teenage girl lying face up, obviously deceased.

Rodriguez immediately radioed for backup and secured the scene.

He approached the woman first, hand resting near his weapon out of instinct, though this elderly woman clearly posed no physical threat.

Ma’am, I’m Deputy Rodriguez.

What happened here? Vera looked up at him with an expression he couldn’t read.

Not grief, not shock.

Something closer to confusion mixed with defiance.

She wouldn’t listen, Vera said simply.

I was disciplining her.

Rodriguez knelt beside Ashley’s body, checking for signs of life, though it was clearly feudal.

Her skin was cool.

The discoloration, the blood from her nose and mouth, the obvious depression in her skull.

These weren’t injuries from a fall or accident.

He stood slowly processing what he was seeing.

“How did you discipline her, ma’am?” “I sat on her,” Vera replied matterofactly.

“To teach her respect.

She kept talking back.

I had to show her I was serious.” Rodriguez felt his stomach turn.

12 years in law enforcement had exposed him to domestic violence, child abuse, accidents, suicides.

But this was different.

a grandmother calmly explaining how she’d crushed her 16-year-old granddaughter under her body weight as punishment.

The ambulance arrived within minutes.

Paramedics confirmed what Rodriguez already knew.

Ashley Miller had been dead for at least 20 minutes, possibly longer.

They documented time of death as approximately 1:20 p.m.

based on body temperature and rigor mortise patterns.

By 2:15 p.m., the house was filled with law enforcement.

Crime scene investigator Linda Martinez began documenting everything.

She photographed the living room from multiple angles, measured the indentation in the carpet where Ashley’s body had been, collected blood evidence, documented the walker, the recliner, the couch arm that showed palm prints where Vera had braced herself.

The carpet told its own story.

fibers were matted down in a body-shaped pattern compressed by extraordinary weight sustained over time.

Around the indentation, scratch marks, evidence of Ashley’s fingers clawing at the carpet, trying to find purchase, trying to push herself free.

The desperation in those marks was haunting.

Martinez documented blood spatter on the couch.

small drops indicating a moment when Ashley had coughed or expelled air from her lungs.

Blood on the carpet where her face had been, a smear pattern showing where her head had moved slightly, struggling for air, trying to turn.

Dr.

Patricia Chen, the medical examiner, arrived at 4:30 p.m.

to conduct a preliminary examination before the body was transported.

She knelt beside Ashley, examining the visible injuries with professional detachment that masked personal horror.

Severe mechanical esphyxiation, Dr.

Chen noted, recording observations, peticial hemorrhaging in the eyes and face, levidity pattern consistent with being face down for extended period, multiple rib fractures, bilateral, and this skull fracture.

She paused, photographing the depression at the back of Ashley’s head.

The force required to fracture a skull this way while the victim is on a carpeted surface is extraordinary.

We’re talking about sustained pressure over time, not acute impact.

Martinez also documented Vera’s living space.

The recliner worn down on one side from years of sustained weight.

The walker modified with extra support bars.

Throughout the house, religious materials, Bibles, pamphlets, magazines about Christian parenting, all emphasizing discipline and obedience.

She marinated in this ideology.

Martinez would later testify.

Every surface reinforced these beliefs about children needing to obey, about discipline being love, about authority being absolute.

She created an echo chamber with no outside perspective to challenge her.

In the back bedroom, they found Ashley’s overnight bag.

still unpacked on the floor.

Inside, three changes of clothes, a phone charger, a book for English class, and a journal.

The journal’s final entry, dated March 13th, would become crucial evidence.

Ashley’s own words describing feeling misunderstood, wanting her parents to see her, questioning why being herself wasn’t enough.

That journal would be read in court, would be quoted in news articles, would become Ashley’s voice speaking from beyond death, forcing everyone to confront what had been lost.

Meanwhile, at the Lee County Sheriff’s Office, Detective Lawrence Hartman sat across from Vera Thompson in interview room B.

Despite being under arrest for her granddaughter’s death, Vera showed no outward emotion, no tears, no distress, just calm, almost clinical detachment.

The interrogation was recorded.

The footage would later be shown at trial, generating both outrage and disturbing fascination.

Hartman started with basic questions, establishing timeline and facts.

Then he moved to the critical issues.

Mrs.

Thompson, I need you to tell me what happened today with your granddaughter.

She was disrespectful, Vera began, voice steady.

Her parents sent her to me because they couldn’t control her.

That’s what happens with soft parenting.

Children need firm guidance.

They need to understand adults are in charge.

Can you describe what you did when Ashley was being disrespectful? I told her to lie on the floor face down.

That’s how discipline works.

You make them submit.

Show them they’re not in control.

She argued at first, but I made her comply.

Then I sat on her.

Not my full weight initially.

I used the couch arm for support, but she kept squirming.

kept trying to argue even while she was down there.

So, I committed fully, put my weight on her back to teach her that when adults give orders, children obey.

No arguments.

How long did you remain on Ashley? Vera paused, considering.

Maybe 20 minutes, maybe longer.

Time is hard to judge.

She stopped moving after a while.

I thought she’d learned her lesson, that she was being quiet and obedient like she should have been from the start.

Did Ashley say anything while you were sitting on her? Another pause longer this time.

She said something about not being able to breathe, but children exaggerate during discipline.

They try to make you feel guilty so you’ll stop.

My mother taught me that you can’t give in to manipulation.

Hartman kept his voice carefully neutral.

Mrs.

Thompson, your 16-year-old granddaughter told you she couldn’t breathe and you didn’t get off her.

Do you understand she was dying? I didn’t realize it was that serious, Vera said, showing no change in expression.

I thought she was being dramatic.

Teenagers are dramatic.

When did you realize something was wrong? When I got up and she didn’t move.

Her face looked strange.

That’s when I called 911.

You called 911 at 1:43 p.m.

The medical examiner estimates Ashley died around 1:20 p.m.

That’s approximately 23 minutes.

Why did you wait? I had to get back to my chair.

Had to think about what to do.

It’s not easy for me to move quickly.

Did you try to help Ashley? CPR.

Check if she was breathing.

I couldn’t get down on the floor like that.

And I thought maybe she was just unconscious that she’d wake up.

Hartman leaned forward.

Mrs.

Thompson, I need to be very clear.

Your granddaughter is dead.

She died because you sat on her with your full body weight for over 30 minutes while she begged you to stop.

Do you understand? You killed her.

Vera was silent for a long moment.

When she spoke, her voice carried frustration rather than grief.

I didn’t mean to kill her.

I was trying to teach her.

That’s what discipline is.

Children today don’t understand consequences.

I was doing what her parents should have done years ago.

I was trying to help.

That statement, I was trying to help, would become one of the most disturbing elements of the case.

Even after being told her granddaughter was dead, even after describing in detail how she’d crushed a child, Vera still believed she’d been right, that she was the victim of misunderstanding, that modern society simply didn’t understand proper discipline.

Back at the crime scene, investigators subpoenaed phone records from Jennifer and Robert Miller.

They found texts exchanged after dropping Ashley off.

Jennifer to Robert.

Mom will straighten her out.

She always did with me.

Robert’s response.

I hope so.

Worried about Ashley, but maybe old school discipline is what she needs.

These texts would haunt the parents.

They showed active desire for stricter discipline.

Showed belief that Vera’s methods would help.

showed trust that proved fatal.

Investigators also interviewed neighbors and former co-workers.

A pattern emerged.

Vera had always been harsh, uncompromising, rigid, but most people assumed it was just her personality.

Her generation, nobody suspected the depths of her willingness to use physical domination as correction.

Patricia Walsh, a former neighbor, told investigators 15 years ago, maybe longer, Vera was babysitting Ashley.

She was about 2 years old.

The baby was crying.

Vera came out on the porch holding her and said to me, “Clear as day, children need to learn crying doesn’t get them what they want.

Sometimes you have to let them cry until they understand nobody’s coming.” It gave me chills, but I never thought she’d take it this far.

Dr.

Dr.

Chen completed Ashley’s autopsy the following day.

The report was 32 pages of medical terminology, translating to one conclusion.

Ashley Miller had died a slow, painful, terrifying death.

Cause of death, mechanical esphyxiation with contributing traumatic skull fracture.

Manor of death, homicide.

Time of death.

Between 1:15 p.m.

and 1:25 p.m.

on March 15th, 2019, detailed findings showed extensive trauma.

Bilateral rib fractures numbers 4 through 9 on the right, 5 through 8 on the left.

Fractures were acute, occurring at time of death.

Chest compression prevented normal respiratory function.

Lungs showed hypoxia and internal hemorrhaging, peticial hemorrhaging in both eyes from blood vessel rupture.

Most significant depressed skull fracture measuring approximately 4 cm in diameter.

The force required to fracture a skull this way while lying on carpet indicated extraordinary sustained pressure.

Underlying brain tissue showed contusion and bleeding.

Defensive wounds on palms and fingers suggested Ashley tried to push up or claw free.

Abrasions on knees and elbows consistent with attempting to crawl.

bruising on forearms where she tried to leverage herself upward.

Time to death.

Based on asphyxiation patterns, Ashley likely lost consciousness within 8 to 12 minutes of compression beginning.

Death occurred within 30 to 35 minutes.

The prolonged nature meant significant distress, panic, and suffering before consciousness faded.

Dr.

Chen would later testify, “In 30 years as a medical examiner, I’ve never seen a case like this.

The mechanism of death, a grandmother using her body weight as a lethal weapon is unique in my experience.

What makes it particularly tragic is that at multiple points during those 35 minutes, if the perpetrator had simply stood up, the victim would likely have survived.

This wasn’t instant.

This was sustained action with multiple opportunities to reverse course.

Those opportunities were not taken.

The evidence was overwhelming.

The confession was clear.

The medical findings were damning.

Vera Thompson had killed her granddaughter through deliberate action sustained over 35 minutes.

Whether she intended death or just intended domination became the legal question, but the result was the same.

A 16-year-old girl was dead, and the person who was supposed to protect her was the one who killed her.

This channel exists to tell these difficult stories, to shine light on tragedies that force us to examine our beliefs about children.

authority and where the line between correction and cruelty truly lies.

Thank you for your incredible support in making this work possible.

If you value content that goes deep, that doesn’t shy away from uncomfortable truths.

Consider joining our YouTube membership today.

Members get access to exclusive content, behindthe-scenes research, and early access to upcoming documentaries.

Your membership helps us keep creating the stories that need to be told.

Jennifer and Robert Miller received the call at 2:30 p.m.

on March 15th.

They’d spent Saturday morning running errands, grocery shopping, hardware store, ordinary weekend tasks.

They’d even discussed how to approach Ashley when she came home Sunday.

Maybe they’d been too harsh.

Maybe they needed to listen more.

Jennifer answered an unfamiliar number.

Detective Lawrence Hartman identified himself and asked them to come to the station immediately.

It was about their daughter.

Jennifer’s heart dropped.

Had Ashley run away, called police? Was she in trouble? Just tell me if my daughter is okay, Jennifer said, voice rising.

The pause was too long.

Mrs.

Miller, I’m very sorry to inform you that your daughter has passed away.

We need you at the station to explain what happened.

I’m very sorry for your loss.

The phone slipped from Jennifer’s hand.

She heard the detective’s voice, small and distant, still speaking.

But the words didn’t matter.

Her daughter was dead.

Ashley was dead.

Robert picked up the phone, spoke briefly with the detective, got the address.

He looked at his wife, who had collapsed against the kitchen counter, making sounds he’d never heard from her.

Animal keening, raw and broken.

They drove to the station in shock, both trying to understand.

An accident, medical emergency? Had Ashley hurt herself? Nothing made sense.

Detective Hartman sat them in a small interview room and explained.

Ashley hadn’t had an accident.

There was no medical emergency.

The person responsible was Jennifer’s mother.

Vera had confessed to sitting on Ashley as discipline.

The medical examiner estimated compression lasted 35 minutes.

Cause of death was asphixxiation and traumatic skull fracture.

Jennifer kept saying she didn’t understand.

Her mother wouldn’t.

She was strict but wouldn’t.

This didn’t make sense.

Mrs.

Thompson confessed to sitting on Ashley as punishment.

Hartman explained carefully.

She stated Ashley was disrespectful and needed to learn a lesson.

The medical examiner estimates your daughter was under your mother’s weight for approximately 35 minutes.

Ashley died from being unable to breathe.

Robert stood suddenly, knocking over his chair.

“You’re saying my mother-in-law killed our daughter? She crushed her as punishment?” Hartman nodded.

“We trusted her,” Jennifer whispered.

“We thought Ashley would be safe.

We thought she couldn’t finish.

The reality was too enormous.

They’d sent their daughter to the person who would kill her.

That first night passed in a blur.

They drove home separately, unable to speak.

The house looked the same.

Nothing had changed physically, but everything had changed fundamentally.

Ashley’s bedroom upstairs, her backpack by the door, her shoes in the entryway, all suddenly transformed into artifacts of a life that no longer existed.

Jennifer went directly to Ashley’s room and collapsed on the bed.

Robert stood in the doorway, unable to enter.

He could smell his daughter’s shampoo, see her posters on the walls, notice homework scattered across her desk.

Friday afternoon, she’d been sitting right there arguing about having to go to her grandmother’s.

For Jennifer, the guilt was immediate and crushing.

Every decision, every moment replayed endlessly.

Why had she insisted Ashley go? Why hadn’t she listened when Ashley said she didn’t want to? How had she not known her mother was dangerous? Jennifer’s sister, Carol, flew in from Arizona the next day.

She would later describe those first days.

Jennifer just shut down, wouldn’t eat, wouldn’t sleep.

She’d sit in Ashley’s room for hours holding her clothes, anything that still smelled like her.

And she’d cry in a way that didn’t even sound human, like something was being torn out of her chest.

She kept saying, “I gave her to the person who killed her.

I put her in the car.

I drove her there.

I kissed her goodbye and left her to die.” Police said Jennifer couldn’t see Ashley’s body yet.

It was evidence.

There would need to be an autopsy.

She could see her daughter after the medical examiner finished.

The thought of Ashley in that cold room alone being examined like evidence, it was unbearable.

Robert handled grief differently.

While Jennifer collapsed inward, Robert needed action.

He paced the house, called lawyers, demanded answers from police, wanted to know what would happen to Vera, how quickly she’d be prosecuted, what her sentence would be.

But underneath the anger was self-hatred.

Robert had agreed when Jennifer suggested sending Ashley to Verus.

He’d thought Ashley needed tougher discipline.

His last real conversation with his daughter had been an argument.

He’d failed her.

His brother Thomas stayed with them the first week.

He later recalled, “Robert couldn’t sit still.

He’d walk room to room picking things up and putting them down, checking his phone every 30 seconds.

One night around 2:00 in the morning, I found him in the garage punching the wall.

His knuckles were bleeding.

He just kept saying, “I failed her.

I was supposed to protect her and I failed.

Robert also handled practical decisions Jennifer couldn’t face.

Calling Ashley’s school, notifying extended family, contacting a funeral home, planning his 16-year-old daughter’s funeral.

Each phone call was agony, having to say the words, “Our daughter has died.” Having to explain or not explain because how do you explain this? Having to hear shocked silence followed by inevitable questions.

Robert found himself saying, “It’s complicated.

There’s an investigation.

We’ll share more when we can.” Because the truth was too horrible.

The truth was that his mother-in-law had crushed his daughter to death.

News spread through the community rapidly.

By Saturday evening, the story hit local news.

By Sunday, it was regional.

By Monday, national headlines were sensational.

Comments sections were vicious.

Some people expressed outrage at Vera, others made cruel jokes, some blamed the parents, and some disturbingly defended Vera’s right to discipline however she saw fit.

The Miller home became a makeshift memorial.

Neighbors left flowers, cards, stuffed animals, candles.

Some knocked to offer support, others wanted details.

Robert stopped answering.

Ashley’s friends organized a vigil at the high school on March 18th.

Over 300 students showed up crying, holding candles, sharing memories.

Her best friend, Madison, gave a brief speech about how Ashley was funny, kind, trying to figure out who she was, like all of them, about how she didn’t deserve to die because she was acting like a normal teenager, about how scared she must have been in those final moments, how alone, how much pain she was in.

In the days following Ashley’s death, cracks in Jennifer and Robert’s marriage began to show.

Grief affects people differently.

Sometimes it brings people together.

Sometimes it tears them apart.

Jennifer couldn’t look at Robert without seeing his agreement to send Ashley to Vera’s house.

Robert couldn’t look at Jennifer without seeing her mother’s face.

They moved around each other like ghosts, unable to connect.

Arguments started, small at first, over logistics, over funeral arrangements, but they quickly escalated into recriminations.

“This was your mother,” Robert would say.

“You agreed to send her,” Jennifer would snap back.

Round and round, blame circling between them, never landing anywhere satisfying because they were both responsible.

Both had made the decision.

Both had trusted Vera.

both had failed to protect their daughter.

On March 19th, 4 days after Ashley’s death, Jennifer and Robert were finally allowed to see their daughter’s body at the funeral home.

Jennifer insisted on going, despite Robert’s attempts to convince her otherwise.

The funeral director led them to a private viewing room.

Ashley was lying on a table covered with a sheet to her shoulders.

They’d done their best to make her presentable, but Jennifer could still see traces of trauma.

the discoloration on her face, the swelling, the way her head rested at an odd angle.

Jennifer approached slowly, reached out and touched her daughter’s hand.

“Cold? Too cold.

The hand she’d held a thousand times.

Cold and still and lifeless.

“I’m so sorry, baby,” Jennifer whispered.

“I should have listened.

I should have protected you.

I failed you.” Robert stood back, unable to approach, unable to see his little girl this way.

He turned and walked out.

And in the hallway, he finally broke down completely, collapsing against the wall, sobbing.

Inside, Jennifer stayed with Ashley for 30 minutes, talking to her, apologizing, telling her all the things she wished she’d said when her daughter was alive, about how proud she was, about how much potential Ashley had, about how she’d taken teenage rebellion too seriously.

Ashley Miller’s funeral was held at Grace Community Church on March 23rd, 2019.

The church held 200 people.

Over 400 showed up.

Her casket was white, covered in pink roses.

Photos surrounded the altar.

Ashley as a baby, a child, a teenager, smiling, alive, gone.

Robert gave the eulogy, voice cracking immediately.

He spoke about Ashley being smart, funny, stubborn, about how she challenged him, made him question his decisions, about how she was becoming an incredible young woman and he’d never forgive himself for not seeing that clearly enough while she was here.

He told the congregation that Ashley was trying, trying to figure out who she was, trying to navigate school and relationships and family expectations, trying to find her voice.

She wasn’t perfect, but she didn’t need to be perfect.

She just needed to be seen, heard, loved for exactly who she was.

And we failed her,” Robert said, sobbing openly.

“Now, my wife and I, we failed her.

We prioritized obedience over understanding.

We sent her to someone we trusted, and that person killed her.

Our daughter died thinking we didn’t love her enough to protect her.

That’s something Jennifer and I will carry for the rest of our lives.

By the end, half the congregation was crying.

The other half sat in stunned silence, processing the weight of what had been said.

Ashley was buried at Eternal Garden Cemetery.

The headstone read, “Ashley Marie Miller, 2002 to 2019.

Beloved daughter, gone too soon.

Forever in our hearts.” what it didn’t say.

Killed by someone who claimed to love her.

Victim of discipline taken to its darkest conclusion.

A life ended by the person her parents trusted most.

Vera Thompson was arrested at the scene on March 15th at approximately 2:20 p.m.

due to her size and mobility issues transporting her required special accommodations.

A medical transport van was called.

Vera was secured and taken to Lee County Jail, booked on charges of secondderee murder.

Her first court appearance was March 18th via video link.

She appeared on screen in an orange jumpsuit specifically sized for her supported by a wheelchair.

Judge Thomas Martinez read the charges.

Mrs.

Thompson, you are charged with one count of secondderee murder in the death of Ashley Miller.

Do you understand these charges? Yes, your honor.

How do you plead? Her attorney, public defender Samuel Briggs, leaned in.

My client pleads not guilty, your honor.

The courtroom erupted.

Jennifer lunged forward in her seat.

Robert had to physically restrain her.

The idea that Vera was pleading not guilty after confessing after the evidence felt like a slap.

Bail was set at $500,000.

Given Vera’s limited income, she would remain in custody until trial.

Her attorney indicated they would pursue a defense based on lack of intent and diminished capacity.

Samuel Briggs faced an uphill battle.

His client had confessed.

The evidence was overwhelming.

The medical examiner’s report was damning, but he had a job to provide the best defense possible within legal constraints.

His strategy relied on three arguments.

Lack of intent to kill.

Vera intended discipline, not murder.

potentially reducing charges to manslaughter.

Diminished capacity.

Vera’s age, health conditions, isolation, and mental state impaired her judgment.

Cultural defense.

Vera’s generation normalized physical discipline.

What modern society views as abuse, Vera viewed as appropriate parenting.

The prosecution, led by assistant state attorney Maria Rodriguez, pushed back hard.

Intent could be inferred from actions.

Vera sat on Ashley for 35 minutes while the girl begged for mercy.

She heard her granddaughter say she couldn’t breathe and chose to remain in position.

She waited 20 minutes after Ashley stopped moving before calling 911.

These actions demonstrated at minimum depraved indifference to human life, satisfying the legal standard for secondderee murder.

The defense hired Dr.

Richard Thompson to conduct a psychological evaluation.

He spent 12 hours over three sessions interviewing Vera.

His report submitted in July 2019 painted a complex picture.

Vera presented with rigid cognitive patterns consistent with her age, upbringing, and prolonged isolation.

She demonstrated limited empathy and difficulty understanding perspectives outside her experience.

Her belief system regarding child discipline was deeply entrenched and resistant to contrary information.

Cognitive testing revealed mild impairment consistent with earlystage vascular dementia.

Memory function was relatively intact, but executive function, the ability to adapt behavior in real time and assess consequences, showed deficits.

Vera demonstrated what Dr.

Thompson characterized as moral fixation.

She’d constructed a worldview where physical discipline was not only acceptable, but necessary.

And this worldview had calcified over decades without external challenge.

Isolation meant she had no social feedback to moderate her beliefs.

However, Dr.

Thompson noted that Vera understood her actions led to her granddaughter’s death.

She comprehended cause and effect.

She understood that sitting on Ashley caused Ashley to die.

What she struggled with was accepting that intent didn’t excuse outcome.

In her mind, because she meant well, she shouldn’t be held fully responsible.

This wasn’t legal insanity.

Vera knew the nature of her actions.

She knew right from wrong legally.

But her moral framework was so distorted, she genuinely believed crushing a child under her weight was acceptable disciplinary practice.

The prosecution’s expert, Dr.

Patricia Winters, evaluated Vera independently and reached different conclusions.

While Vera showed some cognitive decline, it wasn’t significant enough to impair understanding of her actions or their consequences.

She demonstrated clear memory.

She could articulate cause and effect.

She understood that applying significant weight to a person’s chest prevents breathing.

The defense’s characterization of her beliefs as cultural or generational was, in Dr.

Winters’s professional opinion, a distortion.

Yes, corporal punishment was more common in previous generations, but even in the 1950s and60s, sitting on a child with lethal force was recognized as abusive and dangerous.

This wasn’t standard discipline of any era.

Vera’s actions demonstrated what Dr.

Winters called malignant authoritarianism, a belief that she had absolute power over her granddaughter’s body and the right to use that power without limitation.

When Ashley expressed physical distress, Vera made a conscious choice to continue.

That choice reflected at minimum extreme recklessness amounting to depraved indifference.

The trial of Vera Thompson began January 13th, 2020, nearly 10 months after Ashley’s death.

The courtroom was packed.

Media presence was extensive.

Jennifer and Robert sat in the front row directly behind the prosecution table, staring at the back of Vera’s head.

Assistant State Attorney Maria Rodriguez stood before the jury and delivered an opening statement that left several jurors visibly shaken.

Ladies and gentlemen, this is a case about trust betrayed, about authority weaponized, about a 16-year-old girl who died begging for mercy while the person who was supposed to protect her chose cruelty instead.

Ashley Miller was not a bad kid.

She was a normal teenager, emotional, sometimes defiant, testing boundaries like every adolescent does.

Her parents thought sending Ashley to her grandmother would teach respect.

They thought wrong.

Rodriguez explained that over the next two weeks, jurors would hear testimony from medical examiners, law enforcement, forensic experts.

They would see crime scene photos that would disturb them.

They would hear a recording of the defendant’s confession.

The defense will try to convince you that Vera Thompson is a confused old woman who made a terrible mistake, that she didn’t intend to kill Ashley, that her generation just handled discipline differently.

Don’t be fooled.

Intent doesn’t require planning.

Intent can be inferred from actions.

When you sit on a child with nearly a thousand pounds of weight, when that child tells you she can’t breathe, when you hear her gasping and struggling beneath you, and you choose to remain in position, that is intent, that is depraved indifference to human life, that is murder.

Rodriguez concluded by asking jurors to hold Vera Thompson accountable, to say clearly that no cultural belief, no generational difference, no religious conviction excuses crushing a child to death.

to deliver justice for Ashley Miller, who deserved so much better.

Several jurors were already crying.

Jennifer sobbed openly.

Vera sat motionless, expression blank, as if Rodriguez was describing someone else’s crime.

Samuel Briggs faced an almost impossible task.

Humanize Vera Thompson.

His opening statement attempted to create reasonable doubt about intent.

What happened to Ashley Miller is a tragedy.

No one disputes that.

My client does not dispute that.

She knows her actions led to her granddaughter’s death.

She has to live with that.

But this case is not about whether Ashley died.

It’s about why she died.

The prosecution wants you to believe that my client, a 72year-old woman with severe health problems and cognitive decline, intended to commit murder.

That simply isn’t supported by evidence.

Briggs explained that Vera grew up in an era where physical discipline was not only accepted but expected.

She was taught that children needed firm guidance.

These beliefs were reinforced by religion, community, her entire life experience.

When her daughter asked for help with Ashley, Vera thought she was being helpful.

She thought she was teaching an important lesson.

She used a method of discipline that had been used on her.

She didn’t understand her weight made this method lethal.

This is not murder, Briggs concluded.

This is a tragic accident caused by generational differences, impaired judgment, and fundamental misunderstanding of appropriate discipline.

My client made a terrible mistake.

But mistakes, even catastrophic ones, are not the same as murder.

Key testimony was devastating for the defense.

Deputy Rodriguez described entering the house and finding Ashley’s body.

described Vera’s calm demeanor.

Her matter-of-fact explanation, “I sat on her to teach her respect.” Dr.

Patricia Chen’s testimony included detailed descriptions of Ashley’s injuries, photos shown to the jury, disturbing images of the skull depression, the bruising, the internal trauma.

Several jurors looked away.

Chen explained, “The force required to fracture a skull in the manner observed would be extraordinary.

We’re talking about sustained pressure over time.

This wasn’t brief.

This was prolonged compression that Ashley’s body simply couldn’t withstand.

When asked if Vera would have been aware she was causing serious harm, Chen replied, “Yes, Ashley would have been moving, struggling, making sounds of distress.

The sensory feedback would have been impossible to ignore.

Either Mrs.

Thompson was aware and chose to continue, or she deliberately ignored obvious signs of life-threatening distress.

Either way, the level of negligence required approach’s intentionality.

Jennifer Miller’s testimony was the emotional centerpiece.

She took the stand on day four, visibly shaking, barely able to look at her mother.

Rodriguez asked her to describe her relationship with Vera.

Jennifer explained her mother had always been strict, sometimes harsh, but she’d never witnessed anything that made her fear for Ashley’s safety.

I thought my mother would protect her, Jennifer testified, crying.

I thought she loved Ashley.

I thought I was helping my daughter by sending her there.

I was so wrong.

I’ll never forgive myself, but I’ll also never forgive my mother for what she did.

The most anticipated testimony never came.

Vera Thompson did not take the stand.

Her attorney advised against it, knowing her lack of remorse and matter-of-fact descriptions would horrify jurors.

Closing arguments lasted 3 hours.

Rodriguez reiterated evidence, medical findings, the confession.

She showed the jury photos of Ashley, alive, smiling, full of potential next to photos of her crushed body.

Don’t let the defense distract you with talk of generational differences and cognitive decline.

Rodriguez said, “Focus on facts.” Ashley said she couldn’t breathe.

Vera heard her.

Vera stayed on top of her for 35 minutes.

That’s not discipline.

That’s murder.

Briggs made one final plea.

My client is not evil.

She’s a 72year-old woman whose entire world view was shaped by a different time.

She made a catastrophic error in judgment.

Hold her accountable, but don’t brand her a murderer.

The jury deliberated for 8 hours.

On January 28th, 2020, they returned with a verdict.

We find the defendant guilty.

Jennifer collapsed in sobs.

Robert closed his eyes, face contorted.

In the gallery, Ashley’s friends hugged each other, crying.

Vera showed no reaction, no tears, no shock, just the same blank expression.

As Vera was wheeled out of the courtroom, Jennifer shouted, “I hope you never have a moment of peace.

You killed my baby.

For the first time since Ashley’s death, Jennifer and Robert grieved together.

Not as a couple who would survive this, but as two parents who’d lost everything and finally seen a measure of justice.

Sentencing was scheduled for March 15th, 2020, exactly 1 year after Ashley’s death.

In murder cases, the sentencing hearing typically includes victim impact statements, giving the victim’s family an opportunity to address the court and the defendant.

Jennifer requested to speak first.

She walked to the podium on unsteady legs, a written statement clutched in shaking hands.

When she spoke, her voice was raw with grief and anger that had been building for 12 months.

Your honor, members of the court, I stand before you as the mother of Ashley Miller, but I also stand here as the daughter of the woman who killed her.

That duality, that impossible, horrifying duality, is something I will carry for the rest of my life.

I loved my mother.

Growing up, she was strict, harsh, but I thought she loved me in her own way.

I thought her discipline came from caring.

I was wrong.

Jennifer’s voice strengthened as she continued, “What my mother did to Ashley wasn’t discipline.

It wasn’t love.

It was domination.

It was cruelty.

It was murder.” Ashley was 16 years old.

She was smart, funny, stubborn.

She had dreams.

She wanted to study art in college.

She wanted to travel.

She wanted a life.

And my mother took that away over a teenage attitude, over back talk, over behavior that required communication, not violence.

She described replaying the moment she dropped Ashley off every single day, seeing her daughter’s face, looking back at her, hearing her mother say she’d straighten Ashley out, getting in her car and driving away, leaving her child with her killer.

That knowledge haunted her every moment.

Had destroyed her marriage, destroyed her ability to function.

But while I carry guilt, my mother, the woman sitting over there, carries none.

She has shown no remorse, no grief, no understanding of what she did.

She killed a child and thinks she was justified.

She thinks discipline excuses murder.

She thinks her generation’s beliefs give her the right to crush someone’s skull.

I am asking this court to impose the maximum sentence allowed by law.

Not for revenge, not for my own satisfaction, but because my mother has demonstrated repeatedly that she does not understand why what she did was wrong.

She is not safe.

She cannot be trusted.

And Ashley’s death, brutal, terrifying, preventable, demands accountability.

Jennifer walked back to her seat sobbing.

Several court observers were crying.

Even Judge Martinez appeared moved.

Robert went next.

His statement was shorter, but equally powerful.

I don’t have prepared remarks like my wife.

I don’t know how to put into words what it’s like to lose your daughter to someone you trusted.