He Bought a Toothless Slave To Entertain His Guests — But That Night, She Bit Back | HO

Prologue: A Night Alabama Tried to Bury

On a storm-torn night in the late 1850s, deep in the swamplands of Calhoun County, Alabama, a slave woman with no teeth walked into the great parlor of the Wexler plantation and sang a song that would end ten men’s laughter forever.

What happened inside that room—beneath the glittering chandelier, between walls painted with tobacco smoke and pride—is still debated by historians, folklorists, and survivors’ descendants.

But one thing is certain:

**Ezra Wexler bought her to entertain his guests.

And before dawn, he was dead.

The house was ash.

And the woman they called “Siba” had vanished.**

The official records claim a fire.

Local rumor insists it was something else.

This is the story investigators reconstructed from scorched ledger books, enslaved witnesses, and the fractured memories of men who survived long enough to talk—and then refused to speak of it again.

Chapter I: The Woman in the Burlap Sack

The night Siba arrived at the Wexler plantation, the wind was sharp enough to flay skin. The shutters rattled like ribs. Even the dogs refused to bark.

Two slave traders dragged her out of their wagon and onto the veranda. They smelled of tobacco, sweat, and the arrogance of men who believed their cruelty was a profession, not a sin.

One yanked the burlap sack from her head.

What the lantern light revealed made Ezra Wexler smirk.

She was thin, small-boned, wrapped in rags damp from travel. Her hair clung to her scalp. Her face was bruised purple at the jawline. And her mouth—when she parted her lips—revealed nothing but smooth gums.

“She ain’t much to look at,” one trader said, laughing. “But she got a trick. One that’ll make your dinner guests howl.”

Ezra arched a brow. He was a man whose wealth was measured not in acres but in how loudly he could humiliate those he owned. His parlor was famous for parties that made even other planters uneasy.

“How old is she?” he asked.

“Could be twenty. Could be forty,” the trader shrugged. “Tried bitin’ her last master. Lost all her teeth for it. Makes her harmless now. Can’t do no damage.”

Ezra circled her the way men circled horses.

“Harmless,” he chuckled. “Good. I need harmless for tonight.”

He tossed a coin onto the trader’s palm.

And with that, Siba—no teeth, no shoes, no past worth recording—became the latest piece in Ezra Wexler’s arsenal of cruelty.

Chapter II: The Scullery and the Warning

That first night, Ezra ordered her chained in the scullery at the back steps. Rain leaked from the roof, dripping into the dirt beneath her feet. Rats skittered along the wall. The overseer left without a word.

Hours later, when the house grew still, Siba lifted her head.

She did not cry.

She did not beg.

She did what she had always done: listened.

Wind moaned through the cypress trees. Laughter drifted from the great room—men’s laughter, swollen with wine; women’s laughter, sharpened by fear. And below it all, a faint heartbeat of music, fiddles played by enslaved hands forced to pretend joy.

Near dawn, a boy crept into the scullery. Caleb, age twelve, barefoot, eyes too old for his small face.

He carried a tin plate.

“You should eat, miss,” he whispered. “Master don’t like ’em fainting. Says he’s got a party tonight. Says you’re the joke.”

Siba lifted her head.

“Party,” she rasped. Her voice was the sound of a chain dragged across stone. “What kind of party?”

“The kind where they drink too much and hurt folks,” the boy murmured.

She studied him.

“What’s your name?”

“Caleb.”

Siba nodded once—a slow, deliberate motion.

“Then you mind what I tell you, Caleb. Stay far from the laughter.”

He didn’t understand.

But he felt the warning.

And he obeyed.

Chapter III: The Parlor of Men Who Thought They Owned the World

By sunset, the house glittered.

Lanterns swung from the wide porches. The parlor was warm with firelight, scented with roasted pork, pipe smoke, and spilled whiskey. Ezra’s guests—ten men of wealth and cruelty—arrived in bright waistcoats and darker intentions.

The women they dragged along wore lace and fear.

When Siba was brought in, the room fell silent—then erupted in laughter.

“She’s toothless!” one planter yelled.

“Bought a hound with no bite!” another cackled.

Ezra raised his goblet, basking.

“This here is Siba,” he announced. “Got her for the price of a broken mule. But I reckon she’s worth more laughs.”

He nudged her forward.

“Sing for us, girl,” he ordered. “Give these gentlemen something from the fields. Something to tickle their ribs.”

She stood barefoot on his prized rug. Her wrists shook from the tightness of the cuffs. The chandelier above her hummed with heat.

Silence stretched.

A servant later testified that the air “felt like the moment before lightning hits a tree.”

Siba lowered her head.

Then she hummed.

Chapter IV: The Song That Should Not Have Been Heard

It began low, like breath through reeds.

A melody so old and heavy that even the fire seemed to flicker in recognition. It was not a song of the fields. It was older—older than cotton, older than chains, older than the men who imagined themselves owners of the world.

Within seconds, the laughter died.

The guests stared, uneasy.

“Enough,” Ezra muttered.

But the song swelled.

It wound through the room like smoke from a smoldering brand. It curled around the chandelier’s crystals. It threaded itself between the boards of the floor. It made the air thicken, made the walls tighten.

One guest’s goblet slipped from his hand.

“What’s she saying?” he whispered.

The overseer stepped forward—but froze as the lantern nearest him exploded in a burst of flame.

The curtains caught fire.

The women screamed.

The men retreated.

And Siba—her mouth bleeding from the pressure of her gums—lifted her head.

Her eyes were wet obsidian.

Her smile was crooked and red.

She did not stop singing.

Chapter V: The One-Eyed Fire

Witnesses disagree on the exact moment panic turned to terror.

Some say it happened when the chandelier began to sway, though there was no breeze. Others say it was when Siba stepped forward, her shackles dragging softly behind her like iron skirts brushing the floor.

Ezra Wexler stumbled backward.

“Stay away,” he hissed.

She kept coming.

“You bought me to laugh at,” she whispered through her broken mouth. “Let me give you something worth remembering.”

Ezra swung his cane.

Siba caught it midair.

The wood splintered in her hand like dry bone.

No one on record has ever explained how a starved woman with no teeth broke a hardwood cane in two.

But what came next is even more impossible.

The chandelier snapped from its chain.

It crashed to the floor in an explosion of glass and flame.

The fire roared upward, swallowing the ceiling.

Siba did not flinch.

She did not scream.

She walked through the embers like they were warm water.

Ezra tried to run.

He made it three steps.

Then he collapsed, clawing at his throat—eyes bulging, mouth twisted open, veins rising like black cords under his skin. Witnesses said it looked as if invisible hands were squeezing the life out of him.

Siba leaned close.

“You took my teeth,” she breathed. “But not my hunger.”

Ezra died staring at her face.

The men who survived that night never described what they saw in her eyes at that moment.

Most refused to speak at all.

Chapter VI: The Vanishing

The fire swallowed the parlor in minutes.

Servants ran for water. Guests smashed windows trying to escape. Horses screamed from the stables. The night wind turned into a howling thing, pushing flames through the hall like a bellows.

By the time anyone reached the parlor again, it was a skeleton of beams.

Ezra Wexler lay dead beside the hearth, his cane snapped in two.

And Siba was gone.

No footprints in the ash.

No trail in the mud.

No blood, no fabric, no sign she had ever existed.

Only her song lingered in the air—thin, rising, dying, rising again.

A hum that investigators later described as “a sound that did not belong to a mortal throat.”

Chapter VII: The Investigation That Found Everything and Nothing

Sheriff Jonah Pike arrived at noon the next day.

He was a slow-talking man, heavyset, with whiskey on his breath and a Bible in his pocket. But even he could not explain what he saw.

A house gutted from the inside out.

Ten men injured.

One dead.

A chandelier melted into a brass puddle.

And in the center of it all—a scorch pattern on the floor shaped like two bare human feet.

“What kind of woman burns a parlor to ash and walks out unmarked?” Pike mumbled.

The overseer, still shaking, replied:

“That weren’t a woman, Sheriff. That was something else.”

Pike dismissed it as hysteria.

But then the witnesses spoke.

The Conflicting Testimonies

Some claimed she walked through fire without burning.

Some swore she rose into the smoke like a ghost.

One insisted he saw hands—black as soot, long as branches—wrap around Ezra’s throat.

Another said the fire “blew backwards,” as if pulled inward by her voice.

Pike wrote none of this in his report.

His official summary reads:

“Fire sparked by lantern accident.

Woman runaway.

Master deceased from smoke inhalation.”

But Caleb—the boy from the scullery—said quietly:

“She told me to stay away from the laughter.”

And he never wavered from that.

Chapter VIII: The Song That Would Not Die

For weeks after the fire, men searched the swamp.

They found no body.

No bones.

No cloth.

Not even a footprint.

But they heard something.

Hunters swore they heard humming on windless nights.

Fishermen claimed to see a woman’s silhouette across the water.

Servants refused to walk near the creek after dark.

They said:

“If you hear her song, don’t listen.

Or you’ll never stop hearing it.”

Ezra’s relatives tried to rebuild the parlor.

The walls were raised.

The floors were nailed.

The chandeliers replaced.

It burned down again within a month.

No explanation.

No accident.

Just fire.

The second blaze left behind the same scorch marks on the floor—two bare feet.

After that, the Wexler land went unsold for decades.

Chapter IX: What Historians Believe Today

Modern researchers have three competing theories.

Theory 1: The Poison Hypothesis

Some believe Siba slipped a toxin into the wine or air.

A plant derivative that triggered hallucinations, panic, or heart failure.

But this theory fails to explain:

flames moving against the wind

lack of burns on her feet

the missing body

the identical second fire months later

simultaneous physical symptoms in multiple men

And it does not account for the testimonies of those who swore they heard her humming in the ashes.

Theory 2: The Abuse-Triggered Episode

Others argue she entered a dissociative state—trauma unleashing strength and defiance.

A psychological break manifesting in extreme physical power.

But a mental break does not melt chandeliers or cause unburned footprints in ash.

Theory 3: The Cultural Ritual Theory

Folklorists believe she tapped into ancestral memory—ritual song, invocation, or trance passed silently through generations.

Not witchcraft.

Not magic.

But something older, less understood.

A kind of spiritual force awakened by injustice.

A power white witnesses had no language for.

This theory, though speculative, aligns most closely with the witnesses’ descriptions.

Chapter X: The Final Word from the Boy Who Survived

Caleb lived to be an old man.

He never left Alabama.

He never forgot the night the parlor burned.

And he never denied what he saw—or what he didn’t.

In one of the last interviews before his death, he said:

“She didn’t need teeth to bite back.

She used her song.

And they heard it.

Lord, they heard it.”

When asked what he thought happened to Siba, he smiled a slow, haunted smile.

“Some women don’t die.

Not when the world owes them too much.”

He refused to say more.

But when pressed, he added:

“If you walk the swamp on the right night,

you’ll hear her hum through the trees.

And if you hear it—

don’t follow.”

Epilogue: The Woman Who Became the Fire

Today, the Wexler plantation exists only as scorch-marked soil and scattered vines. The land was never rebuilt. No one worked it after the war. No developer ever broke it. Even the timber companies stayed away.

Locals claim nothing grows there—not cotton, not corn, not even weeds.

Except lilies.

White lilies.

Blooming every spring.

No one plants them.

No one touches them.

No one explains them.

But on warm nights, when the air hangs heavy and the cypress trees whisper, some swear they still hear it:

A woman humming.

Soft.

Steady.

Waiting.

Ezra Wexler bought a woman he thought was powerless.

A spectacle.

A joke.

A toy.

But that night, she taught every man in the room what fear truly was.

And she burned her story into Alabama soil more permanently than any record book ever could.

Some stories die when the people do.

Hers didn’t.

Because some fires never go out.

They only hum.

News

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!!

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!! Andre Johnson. Inmate #44702….

A Cheating Husband 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐛𝐞𝐝 His Wife 6 Times – She Came Out Of The Hospital And Sh0t Him | HO!!

A Cheating Husband 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐛𝐞𝐝 His Wife 6 Times – She Came Out Of The Hospital And Sh0t Him | HO!!…

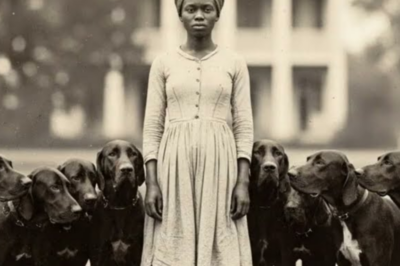

The Baroness Locked Her Slave With 8 Starving Dogs – The Girl Walked Out With All 8 Following | HO!!

The Baroness Locked Her Slave With 8 Starving Dogs – The Girl Walked Out With All 8 Following | HO!!…

Mother Of Three K!lled Cop Husband Over What He Kept In Basement | HO!!

Mother Of Three K!lled Cop Husband Over What He Kept In Basement | HO!! She moved to the window and…

Popular Miami Gold Digger Infected Rich Lovers With 𝐇𝐈𝐕 — It Ended In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

Popular Miami Gold Digger Infected Rich Lovers With 𝐇𝐈𝐕 — It Ended In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!! The Miami skyline…

The Depraved Couple Who Abvsed Their 3 Days Old Daughter, Rec0rd & S0ld The T@pe Online | HO!!

The Depraved Couple Who Abvsed Their 3 Days Old Daughter, Rec0rd & S0ld The T@pe Online | HO!! How that…

End of content

No more pages to load