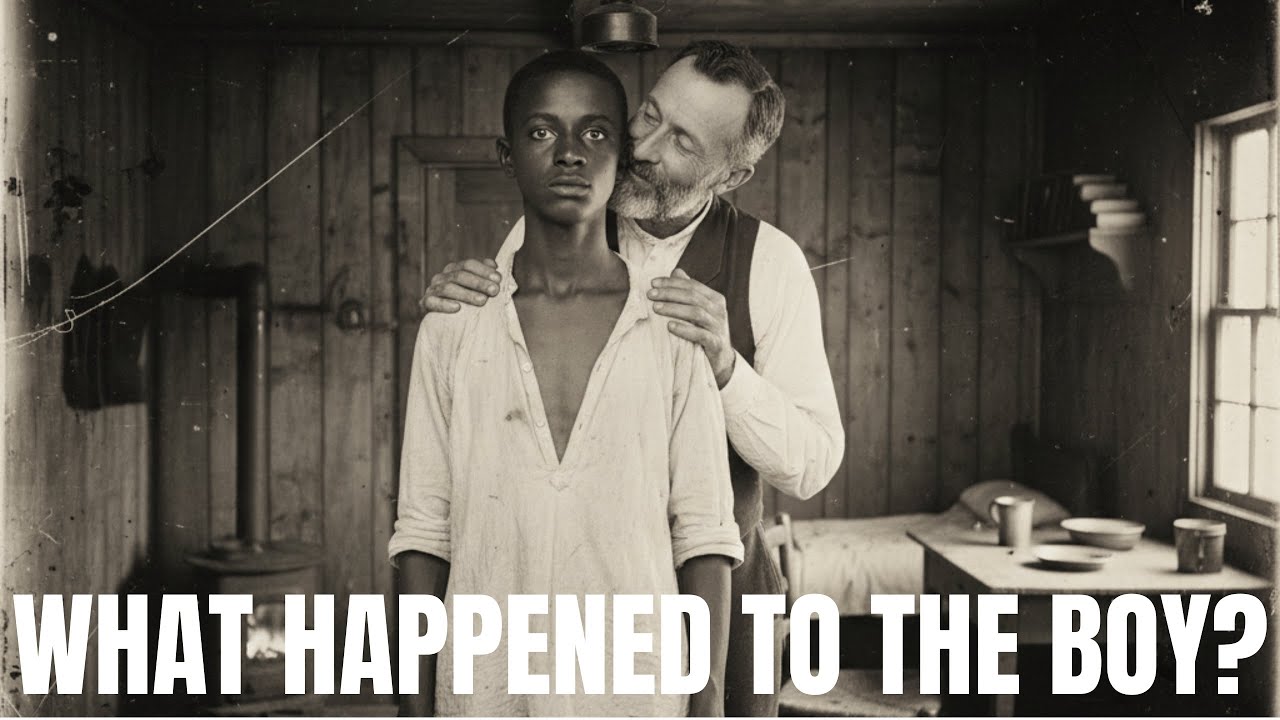

He Called the Boy ‘Special’ Every Night for 7 Years… Then Brought Home a Replacement | HO!!!!

Magnolia Grove and the Man Who Ran It

In 1845, Magnolia Grove Plantation in Mississippi was profitable, orderly, and feared. Its owner, Richard Thornton, relied on an overseer system designed to extract maximum productivity with minimal disruption. The system’s centerpiece was Silas Crowe, a seasoned overseer whose reputation was paradoxical: high yields, few open rebellions, and punishments that appeared less frequent than at neighboring plantations.

That reputation masked a quieter, more devastating form of control—one that operated behind closed doors and left no accounting ledgers.

Crowe was known for requesting young boys as personal assistants. The requests were approved without scrutiny. In a slave economy, such decisions were framed as efficiency, not intimacy. The whispers that circulated—why the same kind of boy, why the same cabin—never reached a forum that could act on them.

Jacob Arrives

Jacob, sixteen years old, arrived at Magnolia Grove as part of an estate purchase from Jackson. He had already endured the defining trauma of slavery: separation from family, years of field labor, and the learned survival strategy of invisibility. He was also intelligent—quick with numbers, attentive to instruction, observant in ways that made overseers take notice.

Intelligence in an enslaved child was dangerous. It made a person valuable—and vulnerable.

During inspection, Crowe selected Jacob for “house duties.” Thornton approved without comment. The decision was framed as a promotion, a reprieve from the fields. For Jacob, it felt like rescue.

Isolation Disguised as Favor

Jacob was moved into Crowe’s cabin and separated from the quarters. His daily life changed abruptly: better food, cleaner bedding, lighter labor, and instruction in reading and writing. Crowe spoke to him often—about discipline, trust, gratitude, and potential. He told Jacob he was different from the others. He told him he was special.

From a modern investigative lens, the pattern is unmistakable. Isolation, preferential treatment, secrets, and language of exclusivity—the classic scaffolding of grooming—were erected quickly and methodically. At the time, there was no vocabulary available to Jacob to name what was happening, and no authority inclined to intervene.

Power Without Witness

What followed over the next years was not recorded in plantation books. It appears instead in post-war testimony collected by the Freedmen’s Bureau—documents that speak in restrained, bureaucratic language while conveying severe psychological harm

Jacob described a relationship defined by coercion wrapped in care. Crowe insisted on secrecy and obedience, framing compliance as proof of loyalty and protection. The “kindness” intensified when Jacob complied and withdrew when he resisted. The message was consistent: safety was conditional.

Researchers today describe this dynamic as traumatic bonding—a psychological attachment formed when an authority alternates reward and threat, leaving the victim dependent and confused about the nature of care.

A Reputation Built on Silence

For seven years, Jacob remained in the cabin. To others on the plantation, he appeared elevated—better clothed, unwhipped, literate. That appearance fostered resentment in some, distance in others. The truth—unspoken and unacknowledged—kept everyone safe in the short term and complicit in the long term.

Crowe’s authority was total. Thornton measured success by output, not by the welfare of those producing it. The system rewarded results and punished disruption. Abuse that did not interrupt the cotton harvest went unseen by design.

The Moment That Shattered the Lie

In March 1852, Jacob overheard Crowe speaking to another boy, newly purchased, using the same phrases—special, chosen, protected. The scene was ordinary to Crowe and catastrophic to Jacob.

What Jacob realized in that moment was not merely betrayal; it was pattern. The bond he had believed unique was a repeatable method. The care he had accepted as singular was a script.

The revelation collapsed the psychological structure that had allowed Jacob to endure. He understood that the privileges he had been given were tools of control—and that he was being replaced.

What Systems Make Possible

This investigation does not turn on individual pathology alone. Crowe’s conduct was enabled by a system that conferred absolute power, removed accountability, and erased consent. Slavery did not merely permit abuse; it normalized the conditions that made it invisible.

Archival scholars note that sexual exploitation of enslaved children is under-documented not because it was rare, but because victims could not report, witnesses could not intervene, and perpetrators had no incentive to record their crimes. What survives in the archive survives by accident—and courage, years later, when survivors testified.

A Record Written After Freedom

Jacob’s account, given in 1865, does not seek absolution. It seeks accuracy. He describes years of confusion, dependence, and shame; the erosion of boundaries; and the realization that harm can masquerade as care when power is unchecked

The testimony forces a difficult question on the reader and the historian alike: How do we assess responsibility inside a system designed to break people?

The Arrival of the “Next” Boy

The new boy arrived in the spring of 1852, younger than Jacob had been when he was selected. He was thin, frightened, and newly separated from family. Silas Crowe introduced him to the cabin with the same practiced language—special, protected, chosen. The repetition was surgical.

For Jacob, the moment confirmed what his instincts had already warned him: what he had experienced was not a relationship; it was a method.

Replacement is a rarely discussed stage of coercive control. Grooming depends on exclusivity; replacement exposes the lie. The psychological effect is destabilizing by design. Victims often describe a sudden collapse of meaning—years of suffering retroactively reframed as interchangeable.

Jacob asked to be returned to the quarters.

Crowe refused.

When Privilege Turns to Punishment

Within weeks, Jacob’s conditions worsened. Meals were reduced. Reading lessons ended. Tasks grew heavier. Crowe’s tone hardened; the nightly reassurances stopped. Where warmth had once been weaponized, coldness now served the same purpose.

Plantation logs note a decline in Jacob’s productivity and an increase in “corrections.” The entries are brief and sanitized—evidence of harm rendered as management. To the system, Jacob had become expendable.

Replacement did not end abuse; it redistributed it.

Collapse and Flight

By late summer, Jacob’s health deteriorated. He experienced insomnia, panic, and disorientation—symptoms modern clinicians associate with complex trauma. He attempted to flee Magnolia Grove twice. The first attempt failed; the second succeeded only because a neighboring plantation was in disarray after flooding.

Jacob disappeared into a landscape hostile to fugitives. He survived by moving at night, accepting food from those who could not shelter him, and avoiding patrols. He would later describe those months as both terrifying and clarifying: terror stripped away illusion.

He never returned to Crowe’s cabin.

The War Changes the Ledger—Not the Past

The Civil War disrupted Magnolia Grove’s operations. Silas Crowe left to join a local militia unit; Richard Thornton consolidated holdings and focused on contracts. The plantation survived. The boys did not become footnotes; they became unrecorded.

After Emancipation, federal agents began collecting testimony. The Freedmen’s Bureau files include depositions from Magnolia Grove—fragmentary, cautious, and constrained by the language survivors felt safe using. Jacob’s testimony appears among them, notable for its clarity about pattern rather than incident.

He did not name acts; he named control.

The Replacement Speaks

In a separate deposition recorded in 1866, another man—believed by archivists to be the younger boy brought into Crowe’s cabin—described nearly identical treatment. Different dates. Same phrases. Same isolation. Same promises.

The overlap mattered.

Historians emphasize that corroboration is rare in such cases. When it appears, it exposes systemic abuse rather than individual anomaly. The pattern at Magnolia Grove was not a rumor; it was a replicable script.

Why Accountability Never Came

Silas Crowe was never prosecuted. Richard Thornton faced no inquiry. The legal architecture of slavery had erased consent, and Reconstruction’s limited reach prioritized labor contracts over historical justice. The perpetrators aged into obscurity; the victims carried memory.

This absence of accountability is not a failure of evidence; it is a feature of the system that produced the harm. Abuse that does not disrupt profit rarely appears in records designed to track profit.

What the Archive Can—and Cannot—Say

Modern investigators approach these testimonies with care. Silence does not equal consent; brevity does not equal minimization. Survivors often spoke in coded terms because explicit language risked retaliation or disbelief. The record’s restraint is itself evidence of danger.

Researchers cross-reference:

Plantation logs (for changes in status and punishment)

Sales records (for timing of arrivals and “assignments”)

Bureau depositions (for patterns and corroboration)

Post-war affidavits (for retrospective clarity)

Together, they reconstruct harm without reproducing it.

The Long Shadow of Replacement

Replacement compounds trauma. Survivors describe a double injury: the original coercion and the revelation that the bond was manufactured. Shame often intensifies—not because the survivor erred, but because the system trained them to believe uniqueness equaled safety.

Jacob’s later statements reflect this reckoning. He rejected the idea that he had been “chosen” and named what had been done to him as use of power. Naming is not closure, but it is resistance.

Why This Story Matters Now

This investigation is not an attempt to sensationalize historical abuse. It is an attempt to understand mechanism.

How absolute power enables harm

How isolation and privilege function as tools

How replacement reveals method

How archives erase while testimonies persist

The lesson is structural. When systems grant unchecked authority and remove avenues for reporting, abuse becomes efficient—and invisible.

Final Accounting

For seven years, a boy was told he was special.

When a replacement arrived, the truth surfaced: the care was counterfeit, the bond a tactic.

No court corrected the record.

The archive did—slowly, incompletely, and only because survivors spoke.

Their words remain as evidence not just of what happened at Magnolia Grove, but of what happens wherever power is insulated from scrutiny.

News

15 Choir Girls Went On A Competition & Never Returned, 23 Yrs Later They were seen in a Strip club — | HO!!

15 Choir Girls Went On A Competition & Never Returned, 23 Yrs Later They were seen in a Strip club…

The Heartbreaking Truth About Mandy Hansen’s Life On ‘Deadliest Catch’ | HO!!

The Heartbreaking Truth About Mandy Hansen’s Life On ‘Deadliest Catch’ | HO!! To millions of viewers, Mandy Hansen looks like…

Three Times in One Night – While Everyone Watched (The Vatican’s Darkest Wedding) | HO!!

Three Times in One Night – While Everyone Watched (The Vatican’s Darkest Wedding) | HO!! On the night of October…

The FBI Raid on Roddy McDowall Exposed the Dark Truth About 1960s Hollywood | HO!!

The FBI Raid on Roddy McDowall Exposed the Dark Truth About 1960s Hollywood | HO!! For decades, Hollywood remembered Roddy…

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune (Georgia 1831) | HO!!

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune (Georgia 1831) | HO!! Introduction: A Birth…

Bitter dad dumps 80,000 pennies on ex wife’s lawn, then his daughter does something unexpected | HO!!!!

Bitter dad dumps 80,000 pennies on ex wife’s lawn, then his daughter does something unexpected | HO!!!! A Virginia father…

End of content

No more pages to load