He Sold His Body to Save His Wife… Then He Stopped Taking the Money | HO!!!!

INTRODUCTION

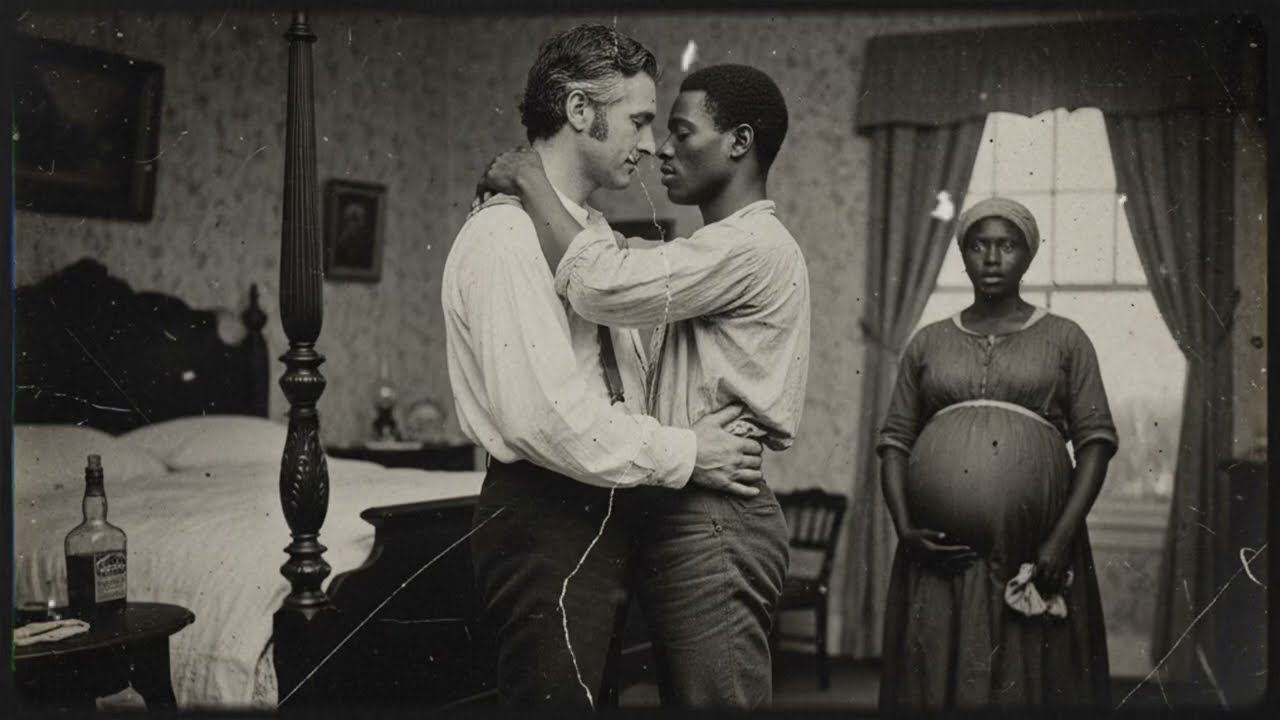

History often preserves the broad architecture of slavery—its laws, its economics, its structural brutality—while losing the intimate, psychologically complex stories that defined life inside that system. The archives record whippings, sales, plantation yields, and census data, but they rarely capture the inner worlds of people forced to navigate impossible choices.

Among the most difficult narratives to reconstruct are those involving coercive sexual relationships between enslavers and enslaved men. The antebellum record documents sexual violence against enslaved women extensively, but the same system also produced cases that defy simple moral categories—situations in which power, survival, desire, and trauma formed relationships that contemporary society refused even to acknowledge.

The story of Nathaniel Pierce, an enslaved man in South Carolina in the mid-1840s, occupies that hidden terrain. It begins with an act of coercion so clear that even modern eyes recognize its violence, and yet evolves into a psychological bond that neither he nor his enslaver fully understood. It exposes an economy of exploitation that operated behind locked doors, far from the public performances of morality in which planters frequently engaged.

And it reveals how a man who sold his body to save his wife’s life eventually stopped taking the money—not because the abuse ceased, but because the relationship had shifted into something his contemporaries lacked language to describe.

This article reconstructs that story—not as melodrama, but as an examination of the complex psychological landscape that enslavement created. It is a world in which moral agency was systematically stripped away, leaving behind a field of constrained choices, coerced intimacies, and consequences that extended far beyond the plantation’s boundaries.

I. THE SUMMONS

In September 1846, Nathaniel Pierce—twenty-six years old, recently arrived at Riverside Plantation, and newly married—stood outside the door of his enslaver’s private bedroom for the second time. He had been summoned after dark, a time when enslaved labor was supposed to end, and the domestic façade of plantation life gave way to what one former enslaved man once called “the real work of the night.”

His wife Clara, seven months pregnant and dangerously ill, believed he was still in the tobacco fields.

The man who had ordered his presence, Monroe Caldwell, was a respected landowner in Oakmont County: a man known for his calm demeanor, his church attendance, his involvement in local politics, and his public rhetoric about Christian duty. Caldwell belonged to the class of mid-tier planters—not a titan of the lowcountry, but a man for whom reputation was a critical asset.

Inside the locked room, beneath the scent of bourbon and smoke, Caldwell offered Nathaniel a transaction:

$2 for sexual access, in exchange for medicine his wife needed to survive.

The offer was not a negotiation; it was coercion framed as benevolence. As in countless other documented cases, the enslaved person’s consent had no legal meaning. Refusal would bring retaliation. Acceptance meant submitting to a violation of the body and mind.

Nathaniel later told another freedman that he “felt something like death inside” as he agreed.

The money changed hands. The arrangement began.

II. THE ECONOMY OF SILENCE

Monroe Caldwell was not unique among Southern enslavers in cultivating hidden sexual relationships with enslaved people. What made his case distinct was that his desire centered not on enslaved women—a pattern that has been extensively documented—but on enslaved men. Antebellum sources reference this phenomenon in oblique, euphemistic language: “unnatural habits,” “disordered affections,” “peculiar preferences.” Most evidence survived only in court archives, church disciplinary records, and personal diaries never meant to be public.

Caldwell, born into a rigid society that demanded heterosexual reproduction and masculine performance, had spent decades cultivating the appearance of a conventional planter. He married a socially respectable woman, fathered three daughters, and carried himself with the confidence expected of white men in his position.

Privately, he developed a system of coerced transactions with enslaved men. He purchased young field hands from distant markets, selected those he found physically appealing, and made them offers similar to the one he extended to Nathaniel. Those who refused were resold. Those who complied rarely lasted long; once the psychological cost became too high, Caldwell disposed of them through sale to brutal labor camps.

It was a cycle built on absolute power, one that could remain invisible precisely because enslaved men had no legal recourse and no voice in the public sphere. Scholars have since noted that sexual abuse of enslaved men often occurred in isolation, leaving minimal evidence compared with the systemic exploitation of enslaved women.

Nathaniel’s case fits that hidden pattern. But unlike his predecessors, he had something Caldwell desired more than convenience: emotional availability shaped by desperation.

III. A CHOICE THAT WASN’T A CHOICE

Nathaniel and Clara had been sold from Virginia in late 1845 after their previous enslaver’s estate was liquidated. Riverside Plantation offered them continuity—a cabin together, work routines that allowed them to remain near one another, and the possibility of forming a household under the most restricted conditions possible.

When Clara became pregnant in early 1846, the pregnancy quickly became dangerous. She experienced swelling, headaches, bleeding. Plantation medicine was minimal, and enslaved women received only enough care to preserve their economic value. The overseer urged her to continue working. The plantation mistress offered a bottle of patent tonic. Neither was sufficient.

By September, midwives warned that Clara might die without real medical intervention.

Thus, when Caldwell told Nathaniel:

“Your wife will suffer. Your child may not survive. But your dignity will remain intact.”

The coercive nature of the choice was unmistakable. The architecture of slavery ensured that survival often required decisions that defied moral frameworks—decisions made not in freedom, but in desperation.

Nathaniel agreed. And he returned three days later. And again three days after that. Eleven times in the span of three months, he stood at Caldwell’s door, each time carrying the weight of a marriage he was trying to protect and a self he no longer recognized.

Little by little, his body adapted. His mind withdrew. The nausea faded.

The medicine worked. Clara’s health stabilized.

Survival had a cost.

IV. WHEN THE MONEY STOPS

On the night their son was born—December 16, 1846—Nathaniel was summoned again. He went because refusal meant danger. He went because habits form quickly under coercive systems. He went because survival had reshaped the boundaries of what he believed he could endure.

But something shifted that night.

When Caldwell handed him the money, Nathaniel pushed it back.

It was not defiance. It was something harder to articulate—a psychological break, a moment at which the transactional clarity of their arrangement dissolved. Around that time, Caldwell began treating him differently. The planter spoke to him rather than at him. He asked questions. He listened. He touched him not only with the entitlement of an enslaver, but with gestures that resembled tenderness.

This change is recognizable to psychologists as the early stages of trauma bonding—a dynamic in which victims of ongoing coercion attach themselves to their abusers as a survival strategy. Enslaved people had no conceptual vocabulary for such experiences; their world did not allow them to distinguish between the coercive structure and the emotional adaptations it produced.

Caldwell encouraged the illusion of mutuality. He praised Nathaniel’s intelligence. He initiated conversations about books Nathaniel was not allowed to own. He offered him forms of attention none of the enslaved people on the plantation had ever been given.

To enslaved men, whose identities were systematically destroyed by labor, violence, and commodification, even minimal recognition could feel like validation.

For Caldwell, the attention masked the violence of ownership. For Nathaniel, the recognition masked the reality of exploitation.

Historically, this type of dynamic is well documented: enslavers created quasi-romantic illusions to ensure lasting compliance from enslaved partners. Nathaniel’s case, however, reveals how effective such manipulation could be when deployed over months and layered with gratitude, trauma, and prolonged isolation.

V. THE BOND TAKES SHAPE

Between January and March 1847, the relationship evolved in ways that complicated the cruelty at its foundation. Caldwell taught Nathaniel to read—an act prohibited by South Carolina law. He gave him books. He asked for his opinions on political matters and philosophical questions.

In antebellum America, enslaved men were denied intellectual identity. Caldwell’s gesture, though coercive and self-serving, created an emotional dependency Nathaniel struggled to name.

The dynamic echoed patterns identified by modern trauma researchers:

Hypervigilance alternating with moments of connection.

Cycles of threat and reassurance.

Identity erosion accompanied by selective validation.

In such circumstances, victims often internalize distorted narratives about affection, loyalty, and intimacy.

Caldwell blurred every boundary. He called Nathaniel “extraordinary.” He asked about his childhood in Virginia. He inquired about his dreams. He facilitated a two-week trip to Charleston, where he brought Nathaniel into hotels and restaurants under the guise of “personal servant,” then into bed as a lover.

For those two weeks, Nathaniel lived a double existence—publicly subordinate, privately elevated. The contrast destabilized his sense of self. It is likely the first time he felt recognized as a person in years.

Caldwell mistook this psychological dependency for love.

Nathaniel mistook the attention for something voluntary.

Neither interpretation was true.

VI. A MARRIAGE DISINTEGRATES

When Nathaniel returned from Charleston, he found that Clara had been reassigned from housework to field labor. The overseer had retaliated against her to discipline Nathaniel indirectly. The baby was thin from inconsistent feeding. Clara’s hands were blistered from work she was not accustomed to performing.

The gulf between husband and wife widened. Clara noticed the fine clothes. The scent of perfume. The changes in his demeanor. She also noticed the money.

When she confronted him, he confessed—not everything, but enough.

Her response was pragmatic, the response of a woman who understood the mechanics of slavery far better than many historians do:

“Do what you must to keep us alive. But come home.”

It was not acceptance in any modern sense. It was survival reasoning. For enslaved women, the calculus of family protection often required actions that violated personal dignity. Clara’s reaction underscores a reality frequently overlooked: enslaved families were forced to accommodate circumstances they could not control, making decisions inside systems designed to break them.

Nathaniel tried to rebuild the marriage. It was slow, halting work. He remained emotionally distant. Clara’s trust was thin. Their child grew, but Nathaniel felt unable to fully inhabit the role of father.

Meanwhile, Caldwell’s attachment deepened into obsession.

VII. THE PLANTATION BEGINS TO UNRAVEL

By the autumn of 1847, Caldwell’s wife, Abigail, confronted him. Plantation mistresses often suspected their husbands’ involvements with enslaved women. But involvement with enslaved men—if suspected—produced a different level of alarm. Southern masculinity depended on rigid heterosexual norms. Discovery would destroy a planter’s reputation, economic relationships, and political future.

Abigail warned him. Caldwell ignored the warning. She retaliated by undermining his social standing through letters to business partners and quiet rumors about his “instability.” Within months, his economic position began to deteriorate.

At the same time, Nathaniel withdrew, realizing the corrosive effects of the relationship on his marriage and his identity. Caldwell responded with threats—using the language of ownership that shattered any remaining illusion of equality.

When Nathaniel threatened to sever contact, Caldwell ordered Clara to be sold to the Deep South.

It was the moment the mask dropped.

Whatever tenderness Caldwell believed existed evaporated under the reality of absolute power.

Nathaniel begged. Clara intervened. The threat hung over them like a blade.

VIII. BREAKDOWN

What followed in late 1847 to early 1848 was a period of escalating instability.

Caldwell drank heavily. He alternated between pleading and rage. He reasserted dominance when challenged. Nathaniel oscillated between fear, guilt, and a hollow sense of obligation.

These psychological contradictions are common in coercive environments, where victims internalize conflicting identities: the desire to escape, the conditioned urge to placate, the illusion of connection, and the terror of punishment.

Clara, witnessing the unraveling of her husband and the collapse of the plantation, made a bold decision: she approached Caldwell directly.

Her appeal—measured, courageous, and grounded in maternal logic—forced Caldwell to confront what he had become. The weight of her words, combined with his collapsing public life, produced a moment of clarity.

He wrote letters to a Philadelphia Quaker merchant known for purchasing enslaved families and facilitating their eventual emancipation.

He arranged the sale.

And he let them go.

IX. THE EXIT

In early 1848, Nathaniel, Clara, and their son Benjamin boarded a wagon and departed Riverside Plantation forever.

Caldwell watched from his office window. He did not follow. He did not intervene. He did not punish.

Nathaniel never saw him again.

Caldwell’s decline continued. Local records indicate increasing debts, social withdrawal, and signs of mental distress. He disappeared from surviving documents by the mid-1850s—a not uncommon fate among disgraced planters whose private lives unraveled.

What remained was the life Nathaniel had to rebuild in the North—a life shaped by freedom, survival, and the long shadow of trauma.

V. FREEDOM: A DOOR OPENED BY A MAN WHO COULDN’T LET GO

Nathaniel never remembered the actual moment the wagon crossed the Pennsylvania state line.

He only remembered the air.

Cold, northern, thin.

A kind of cold that stung the lungs but meant survival.

Clara wrapped their son in a shawl as the wheels rattled over uneven cobblestone. They reached Philadelphia in the last weeks of winter, the city gray and smoke-stained, but to them it looked almost holy. It was the first place Nathaniel had ever stood where no white man could legally own him.

The Quaker merchant, Isaiah Patterson, greeted them with a warmth that made Nathaniel uneasy. Men like Patterson—educated, gentle, soft-spoken—were not part of his world. Men with voices that held no threat confused him. Patterson shook his hand carefully, as if afraid Nathaniel might recoil.

He did.

For weeks he flinched whenever Patterson reached for anything, even a ledger or a coat. Centuries of instinct do not evaporate at the state line.

Clara adapted faster. She always had.

Within two months she was helping in Patterson’s household, laughing with the other women, practicing reading with them in the evenings. Nathaniel watched her reclaim pieces of herself he hadn’t even known were missing.

He envied her.

He loved her.

He didn’t fully understand her.

Not yet.

Patterson’s offer was clear and radical:

“Three years of honest work, fair wages, no exploitation—and then, if you choose, I will sponsor the purchase of your legal freedom papers. After that, you are no longer my workers. You are simply citizens.”

Citizens.

Nathaniel wasn’t ready for the word.

He didn’t know how to carry it.

But he nodded and accepted the contract.

Because the only alternative was to look back toward South Carolina.

And he would rather have cut off his own hands.

VI. THE SHADOW THAT FOLLOWED HIM

Trauma has a geography.

For Nathaniel, it lived behind closed doors, in lamplit rooms, in any quiet space where a man might speak too softly. He could spend an entire day working with tools, shaping wood, building chairs, repairing shutters—but one gentle voice behind him could send his heart racing.

He hid it well.

Or tried to.

Clara saw everything.

Every tremor in his hands.

Every night he woke gasping.

Every time he held their son stiffly, as if afraid the child would sense the truth inside him.

She never blamed him.

But she never asked, either.

Survival had taught her that some truths only destroy.

During their first Philadelphia winter, Nathaniel began having episodes—moments where he would dissociate, stare at nothing, hands trembling as if some unseen presence hovered just behind him. Clara would guide him to bed, rub his back, whisper prayers.

He never told her the full truth.

He never said that sometimes, when he closed his eyes, he could still feel Monroe’s breath at his ear… not always as violence.

Sometimes as apology.

Sometimes as need.

Sometimes—God forgive him—as tenderness.

Those were the memories that sickened him the most.

The human mind is not built to hold brutality and affection in the same space.

But slavery forced that coexistence.

During one episode, Clara whispered:

“You’re here. Not there. He can’t touch you now.”

He nodded.

But the voice in his memory whispered back:

You’re the only person who ever saw me…

Nathaniel never repeated that line aloud.

Not once.

Not even decades later.

VII. A CONFESSION HE NEVER EXPECTED

The first real turning point in Nathaniel’s healing came from someone he barely knew.

A man named Thomas Wright, older, slow-moving, with the look of someone who had survived different kinds of storms. They were helping expand the local church—an institution built by freedmen brick by brick—when Thomas spoke without looking up:

“You carry shame like a man who had no choice.”

Nathaniel froze.

How could he possibly know?

Thomas continued hammering in a nail.

“I know that look. I had a master once who… expected things. Who asked for things no man should ask another. And he paid. That made it worse.”

Nathaniel dropped his hammer.

Thomas kept speaking, low and steady.

“They twist your body first, then your mind. Make you think you chose it. Make you think the moments that weren’t cruel were affection. Make you think the blame is yours.”

Nathaniel felt something break inside him.

The world had given him no language for what happened with Monroe. Enslaved men were not imagined as victims of such things. They were denied even the dignity of trauma.

And yet here was Thomas, naming the unnameable.

“If you didn’t love him back, why do you feel broken?”

“I don’t know,” Nathaniel whispered.

“Because he gave you scraps of humanity in a place where you were starved for it. That’s how they keep you.”

Nathaniel sat down hard on the church step and covered his face.

For the first time since Philadelphia, he wept.

Not the silent kind he hid from Clara.

Not the terrified kind he had as a child.

But a cleansing, violent cry that shook him to his bones.

Thomas didn’t touch him.

Didn’t offer comfort.

He simply stayed near.

And for Nathaniel, that was enough.

VIII. THE YEARS OF REPAIR

Healing did not happen quickly.

It was not a straight line.

It was not merciful.

It did not care about his timeline.

But it happened.

He learned to hold his son without shame.

Benjamin grew into a bright, curious boy with quick hands and a fearless nature. He followed Nathaniel everywhere, tugging his sleeve, asking how tools worked, how wood fit together, why nails held weight.

Nathaniel answered every question, even when the answers choked him.

He learned to love Clara again.

At first, he approached her carefully, as if she were fragile.

But she wasn’t.

She had survived slavery with her identity intact.

She had carried a family through hell without losing herself.

Over time, intimacy returned—not the passionate kind of youth, but a deeper, slower kind of affection. A quiet companionship.

One evening she took his hand and said:

“You don’t owe me perfection. You only owe us honesty.”

He nodded.

It was the closest he ever came to confessing the whole truth.

He became a carpenter.

A talented one.

Patterson sponsored his apprenticeship, then encouraged him to take on jobs of his own. Nathaniel built tables, repaired staircases, carved intricate frames that customers said were finer than anything imported.

Building things helped him rebuild himself.

For every piece of furniture he sanded smooth, he imagined sanding away memories.

For every table leg he carved, he carved a little more control over his life.

By 1850, Patterson helped the family purchase their freedom fully—signed papers that declared Nathaniel, Clara, and Benjamin “free persons of color.”

Nathaniel framed his documents.

He hung them above the workbench.

He checked them every morning.

IX. THE LETTER HE NEVER OPENED

In 1852, two years after purchasing his freedom, Patterson called him into his office.

He was holding an envelope.

“This arrived from South Carolina,” Patterson said gently.

“I thought you should decide what to do with it.”

Nathaniel stared at the handwriting.

He knew it instantly.

Monroe Caldwell.

His body reacted before his mind did—pulse racing, hands trembling, breath tightening.

He could smell the old cologne.

Could hear Monroe’s voice whispering his name.

Could feel the mix of longing and revulsion twisting in his gut.

Clara stepped into the office.

Patterson handed her the letter too.

She studied Nathaniel’s face.

“Do you want to know what it says?”

“No.”

“Then we burn it.”

She didn’t hesitate.

She took the envelope to the hearth, struck a match, and set it ablaze.

Nathaniel watched the edges curl, the ink blacken, the fire eat the past.

He waited to feel relief.

He did not.

He waited to feel closure.

He did not.

But the letter was gone.

And that, Clara later said,

was the only closure a man like him could ever get.

X. THE WAR THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

When the Civil War began in 1861, Nathaniel was 42.

He did not enlist.

Not because he didn’t care about the cause—he did—but because he knew what battlefields did to men. His mind had already survived one war.

But he contributed.

He built crates for the Union Army.

Helped repair damaged buildings.

Donated a portion of his earnings to abolitionist groups.

During those years, he watched thousands of formerly enslaved people pour into the North seeking refuge. He listened to their stories—stories of beatings, starvation, rape, torture.

Stories far worse than his own.

And each time someone spoke of their trauma, he felt the same ache:

At least their suffering made sense.

Mine… does not fit any category.

He never mentioned Monroe.

Not once.

History would never know that part of him.

XI. THE SON WHO CARRIED THE TRUTH FORWARD

Benjamin grew to be tall, strong, kind.

He married a freeborn woman named Miriam and had two daughters—children who would never know the lash, the auction block, or the quiet horrors of bedroom coercion.

When Benjamin was 17, he asked:

“Papa, why do you wake up crying sometimes?”

Nathaniel said nothing for a long time.

Finally:

“Because memory is not always something you choose.”

It was the safest answer he could give.

When Benjamin was older—after Clara had passed, after Nathaniel’s hair had grayed and his hands stiffened with age—Benjamin pieced together more of the truth.

He had heard whispers from the church elders, fragments from Thomas Wright, and stories passed quietly among free Black communities. He had learned to read faces and silence as well as words.

One evening, Benjamin said:

“Papa… whatever you did to save us… I know it came with a cost.”

Nathaniel closed his eyes.

Benjamin continued:

“You don’t ever have to explain it. You don’t ever have to confess it. You carried the weight so we didn’t have to.”

Nathaniel’s voice broke.

“I wish you didn’t know.”

“I wish you hadn’t lived it.”

Father and son held each other while evening shadows crept across the floor.

Sometimes love is simply acknowledging what cannot be spoken.

XII. THE FINAL YEARS: WHAT A MAN TAKES TO HIS GRAVE

Nathaniel lived to see 1889.

He watched Reconstruction rise and fall.

Watched his grandchildren play in streets he built homes on.

Watched Black men vote for the first time, then watched that right erode again as Jim Crow laws took root.

He saw freedom gained, threatened, reshaped.

He never returned to the South.

Never spoke Monroe’s name again.

Never told anyone the full truth of that year inside Riverside Plantation.

In his final months, he often sat alone on the back porch, carving little wooden figures—small animals, birds, toys for his grandchildren. He carved to keep his hands from shaking. Carved to keep the nightmares away.

One afternoon, shortly before his death, he said to Benjamin:

“Your mother saved me. Patterson helped me. Thomas understood me.

But I never learned to forgive myself.”

Benjamin asked quietly:

“For what?”

Nathaniel answered with a truth only trauma can speak:

“For surviving.”

He died that winter at age 70.

His gravestone reads:

“NATHANIEL PIERCE —

Carpenter. Husband. Father.

A Free Man.”

No one carved the other truth:

The man who sold his body to save his wife…

and then, impossibly,

stopped taking the money because the abuse had turned into something twisted, human, damaged, and real.

XIII. THE INVESTIGATOR’S AFTERWORD

Most histories of slavery focus on the visible horrors—whips, chains, auctions.

But the psychological horrors were often even more devastating:

coerced intimacy

dependent relationships

trauma bonds

exploitation disguised as affection

the erasure of one’s own desires

the inability to define love or violation

These stories were almost never recorded.

Men like Nathaniel carried them silently.

Shame made sure of it.

Racism made sure of it.

History erased them because they didn’t fit the clean categories of “abused” and “free.”

But they existed.

Hundreds of them.

Thousands of them.

Nathaniel’s story—whispered through community memory, reconstructed through testimony, found in a Quaker ledger and a forgotten obituary—remains one of the few we can still trace.

It forces us to confront a truth most people prefer not to know:

Slavery did not just steal bodies.

It stole the ability to understand one’s own heart.

It twisted survival into guilt, coercion into counterfeit affection, violation into confusion.

It left men and women free in name but never fully free in memory.

Nathaniel Pierce survived.

He built a family.

He carved a life.

He died a free man.

But part of him remained in that locked bedroom in South Carolina—

a reminder that freedom does not erase the past.

It only makes room to carry it.

News

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!!

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!! So he hires a French…

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE IT? | HO!!

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE…

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!…

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal | HO!!

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal…

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. | HO!!

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. |…

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender | HO

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender |…

End of content

No more pages to load