His Best Friend Snitched On Him, So He Destroyed 300 People: Kingpin Rayful Edmond III | HO!!

PART 1 — The Making of a Kingpin

On December 17, 2024, inside a halfway house in Cape Coral, Florida, Rayful Edmond III collapsed and died at age 60. He was 325 days away from full release after serving 35 years in federal custody. To most of America, the name barely registers anymore. But in Washington, D.C., especially for those who lived through the crack-era bloodshed of the late 1980s, the name lands like a thunderclap.

Because in the nation’s capital — the city of monuments, embassies, and federal power — Rayful Edmond III became the face of a drug empire that once controlled 60 percent of the city’s cocaine supply. His case triggered unprecedented federal security measures, reshaped the prison telephone system nationwide, and eventually produced one of the most consequential government informants in U.S. narcotics history.

This is the story of how a boy raised in a drug-dealing household became the Kingpin of D.C., how betrayal turned him into a government informant, and how his cooperation helped bring down hundreds — perhaps as many as 300 people — including killers, traffickers, and cartel-level suppliers.

And yet, in the end, the man whose world revolved around survival, loyalty, and power died quietly in a Florida halfway house — one year short of freedom.

A Drug Empire Begins at the Kitchen Table

The official version of his life begins simply enough.

November 26, 1964. Washington, D.C.

Rayful is born to Rayful Edmond Jr. and Constance “Bootsie” Perry, both government employees — respectable on paper. But inside the modest home on M Street Northeast, the real family business was narcotics.

Relatives drifted in and out. Twenty to thirty people sometimes lived there at once. It wasn’t a home — it was a distribution center disguised as a residence.

His mother didn’t hide the business from her children — she trained them. At nine years old, Rayful sat at the kitchen table bagging diet pills for illegal resale to federal employees. That moment would later be captured in wiretap recordings where his own mother admitted:

“When he started out, it was doing hand-to-hand. Then he just got too big, too fast.”

But outside that house, Rayful wasn’t a menace. He was a star.

Popular. Best-dressed. A gifted basketball player. Teachers liked him. Girls chased him. He had the charisma of a born leader — but his leadership training came from narcotics distribution, not corporate mentorship.

College lasted barely a year. He dropped out — not because he lacked ambition, but because he already knew the business he intended to dominate.

By 18, he was cutting cocaine for local dealers. Soon he met Cornell Jones — a heavyweight in the D.C. scene — and Tony Lewis, Sr., the man who would become his closest business partner and mirror image.

Together, they built what resembled a corporation more than a street gang. Sophisticated distribution. Payroll structure. Security infrastructure. Logistics that rivaled Fortune 500 firms.

By the mid-1980s, Washington, D.C. had a new monarchy — and Rayful was King.

The System He Built

The operation wasn’t chaotic street dealing. It was industrial.

Back alleys were engineered with escape routes. Tripwires warned of incoming police. Kids ran lookout teams using pagers and code language. Sales were so frequent witnesses described lines 100 people deep, buying drugs faster than fast-food restaurants served burgers.

Dealers worked eight-hour shifts. Top sellers earned $5,000 a week.

Authorities estimated 30 transactions per minute.

And then came the expansion.

Las Vegas. A boxing match. A chance introduction to Melvin Butler — a California-based trafficker with ties to the Crips and the Cali Cartel.

One shipment turned into many.

Soon 1,700 pounds of cocaine were moving through D.C. every month.

$2 million per week.

150 employees.

A city drowning.

Yet the meeting that would define his fate didn’t happen in a cartel mansion. It happened at a car wash.

The Woman Who Would Destroy Him

She was a 47-year-old white jewelry seller named Alter “Altea” Rae Xanville.

He was 21, rich, powerful, reckless, and curious.

He bought jewelry she didn’t think he could afford. He told her not to worry. Soon she was living in an apartment he paid for, furnishing it with his cash, traveling to Las Vegas with him — and being drawn deeper into his world.

What began as courier work soon turned into trusted co-conspirator status.

In April 1988, she flew alone to Los Angeles carrying $1.5 million in cash to deliver to cartel intermediaries.

The trust he placed in her would cost him everything.

Because when she was later arrested, Alter Rae didn’t go down — she wired up.

She became the federal government’s most valuable witness — and she recorded everyone, including Rayful’s own mother.

A $30,000 bounty was placed on her head.

She went into hiding.

And Rayful’s empire — and family — began to collapse.

Murder in the Nightclub

The violence that followed his rise turned Washington, D.C. into the Murder Capital of America.

One case stood out.

June 23, 1988 — 2:30 a.m. — Southeast D.C.

An argument.

A nightclub called Chapter 3.

An 18-year-old rival — Brandon Terrell — mouths off.

Outside, Rayful gives a signal to his lieutenant, Columbus “Little Nut” Daniels.

Seven bullets.

Terrell drops dead.

Reward: A $50,000 Mercedes-Benz.

A 16-year-old fall-guy tries to take the blame. Police don’t buy it.

And the murders escalate.

Between 1985 and 1989 — D.C. homicide numbers explode.

434 murders in 1989 alone.

Crack emergencies rise 400 percent.

Witnesses vanished.

Others were burned out or killed.

Rayful didn’t need to pull the trigger. He nodded. Others handled the rest.

But in the neighborhood, the story sounded different.

He handed out $100 bills to kids.

Paid rent for neighbors.

Paid for medicines and groceries.

He sponsored youth basketball.

Some called him Robin Hood.

Others called him Death.

Both were right.

The Arrest That Shocked the City

April 15, 1989 — 5:30 p.m.

Federal agents storm multiple properties.

Twenty-nine people are arrested.

The jury is kept anonymous for the first time in D.C. history.

Courtroom surrounded by bulletproof glass.

Rayful is housed on a Marine base and flown to court by helicopter daily.

The danger is real.

One witness is shot dead before testifying. Another’s house is firebombed.

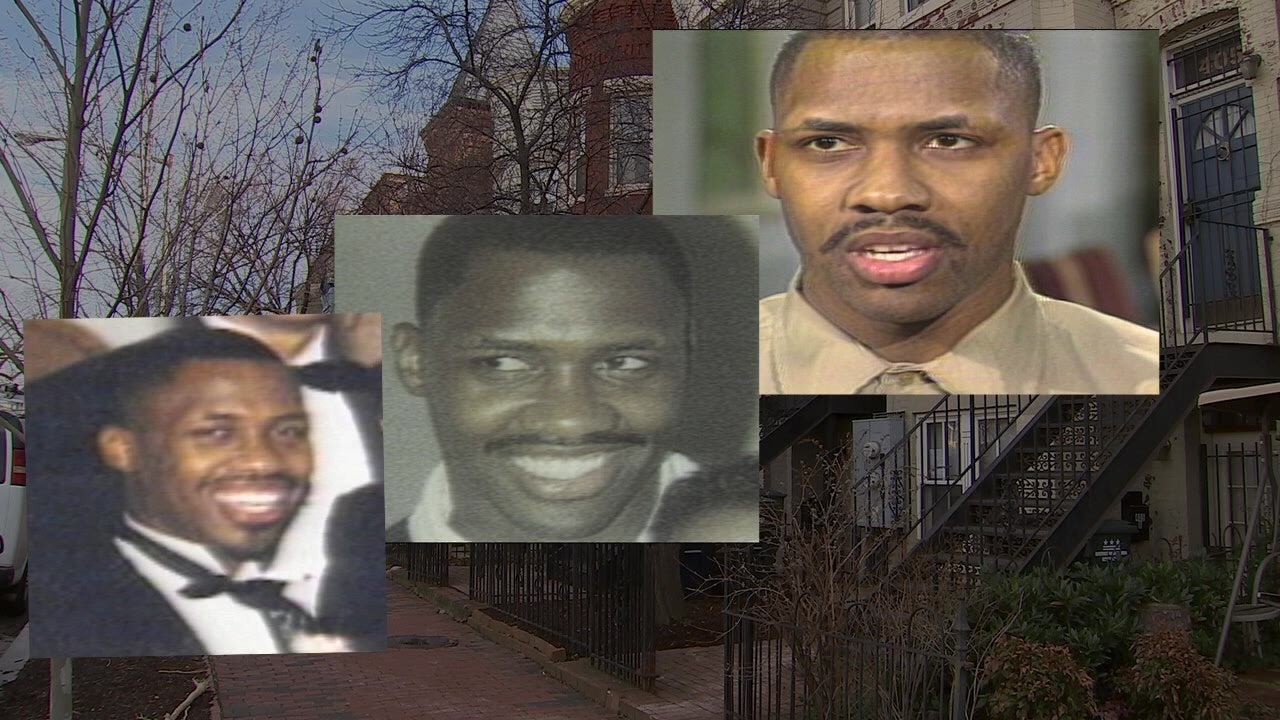

His childhood best friend, Royal Brooks, testifies against him.

He admits storing $3 million in cash and cocaine.

Then Alter Rae takes the stand. Blonde. Calm. Controlled.

And she detonates his world.

Her testimony — combined with his mother’s recorded voice — buries him.

He receives life without parole.

So do members of his family.

His empire is erased.

But his power is not.

Because inside federal prison, Rayful found a way to run an even bigger operation — from behind bars.

And when that operation collapsed, he made a decision that would change American law enforcement forever — and destroy over 300 people in the process.

He became the most powerful federal snitch in the history of Washington, D.C.

And he never stopped.

Not for 24 straight years.

PART 2 — The Snitch Who Brought Down 300 People

When the judge’s gavel dropped in 1990 and the sentence “life without parole” echoed through the federal courtroom, most assumed that Rayful Edmond III’s reign had ended. He was 25 years old and was expected to die in prison. But behind the razor wire and concrete, his influence didn’t shrink — it metastasized.

Federal prosecutors later said flatly:

He moved more cocaine from prison than he did while free.

Running a Drug Empire From a Prison Payphone

Federal archives show that after early custody at USP Marion, Rayful was transferred to USP Lewisburg — a hardened facility filled with lifers, cartel operators, and killers. There, he was placed in proximity to two men who changed everything:

Dixon and Osvaldo “Chicky” Trujillo-Blanco — sons of the infamous Colombian cocaine matriarch Griselda Blanco.

It was a perfect storm.

• They had supply.

• He had distribution networks still operating in D.C.

• They shared the same appetite for risk.

And Lewisburg, at the time, had a vulnerability.

Its phones.

Rayful gained near-exclusive access to multiple lines — calling for hours daily — even placing simultaneous long-distance calls. Investigators recorded 54 calls in a single afternoon connecting four states and two countries. He spoke in layered slang and pig-Latin-based codes that required federal translators to interpret.

By 1992, drug task forces confirmed 1,000–2,000 kilos per week were passing through networks linked to his new cartel contacts. Much of that product traced back to Washington, Maryland, Virginia, Philadelphia, and New York.

Estimations suggested $300 million in drug proceeds moved through the organization during the period he helped coordinate while incarcerated.

Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder — years before leading the Department of Justice — would later remark that Edmond “pushed more cocaine from his cell than from the street.”

And then the federal government caught him.

Wiretaps mounted. Financial trails surfaced. And in 1996, he was convicted again — this time for conducting a criminal enterprise from federal prison.

Sentence added:

30 years — on top of life without parole.

This should have sealed his fate.

Instead, it led to the single most controversial decision of his life.

The Decision That Changed Federal Cooperation Forever

July 1994.

In a modest motel room, away from the prison yard and far from the streets of D.C., federal agents sat across from one of the most feared men of the crack era.

And Rayful Edmond III agreed to cooperate.

The FBI warned him bluntly:

• This will not reduce your sentence

• This will endanger your family

• This will permanently destroy your name

He said yes anyway.

The official narrative says he did it to secure his mother’s release. Constance “Bootsie” Perry — the woman who first taught him to package drugs — had been sentenced to 14 years because of testimony tied to his organization.

But law enforcement veterans — and even members of his former crew — doubt that was his only motivation.

A more pragmatic reality loomed:

He had been caught, yet again, at the center of a massive narcotics conspiracy.

The cooperation gave him leverage — or at least protection — inside a system where enemies multiplied.

And once he began talking, he never stopped.

For 24 uninterrupted years, federal agents met with him multiple times weekly. He decoded recordings like a linguist. He explained process flows, hierarchy, and price dynamics. He mapped supply chains. He identified rival networks and internal traitors.

Former Assistant U.S. Attorney John Dominguez later called him:

“A compass — one that pointed investigators where to go next.”

By the time he was finished:

• 300+ defendants were implicated

• Over 100 were convicted

• 20 previously unsolved murders were closed

• Major trafficking pipelines were dismantled

One federal agent admitted that entire task force strategies evolved from his guidance.

He didn’t simply inform.

He rewrote how narcotics investigations were structured.

And while doing so, he entered the federal Witness Security Program — inside the prison system.

The man once celebrated as the Babe Ruth of Crack now held a different title:

The most valuable snitch in Washington, D.C. history.

A Community Divided Down the Middle

By the time his cooperation spanned a decade, the mythology around him had fractured.

Some called him a traitor — a man who built a kingdom on loyalty, only to violate the very code he enforced.

Others — especially those living with the scars of 1980s D.C. — believed his cooperation finally delivered justice in a city that once averaged more than a killing a day.

So when the government finally moved to reduce his sentence, emotion flooded the city like a returning tide.

October 2019 — Washington, D.C. Federal Court.

For the first time in 17 years, Rayful returned to court — thinner, older, quieter — to argue that his life sentence should be reduced.

Judge Emmet G. Sullivan — a seasoned jurist not prone to dramatics — said openly:

“This is the most challenging decision of my judicial career.”

The Washington Attorney General’s office conducted a public survey of over 500 residents.

The result was nearly a mathematical tie:

50.4% supported his release

49.6% opposed it

No clearer reflection exists of how deeply the city remained psychologically split.

Victims still grieved.

Former rivals still held grudges.

And some old-heads still quietly admired him.

But federal prosecutors — acknowledging the staggering scale of his cooperation — recommended a reduction.

In 2021, Judge Sullivan issued a 72-page ruling, reducing the sentence to 20 years.

Even then — freedom wasn’t immediate.

He still owed 30 federal years from the Pennsylvania conviction. Yet by 2024 — after 35 total years of incarceration — the Bureau of Prisons transferred him to a halfway house.

For the first time since Ronald Reagan was president, Rayful Edmond walked in public without guards.

And then — only months later — it ended.

The Final 325 Days

July 31, 2024. He arrived at a halfway house in Cape Coral, Florida. Gone was the swaggering kingpin who once bought gold-inlaid Jaguars and dropped $10,000 in cash on the street for children to chase.

In his place stood a 60-year-old man hardened by stress, institutional food, and three and a half decades of confinement.

On August 1, 2024, a video surfaced online.

He smiled.

“I’m back. Better than ever.”

Then silence.

For four and a half months, there were no public appearances. No interviews. No memoir. No documentaries. No public apology tour. No visible attempts to reconnect with old allies or make peace with old enemies.

He waited for November 8, 2025 — his projected full-release date.

But on December 17, 2024, he collapsed.

Dead at 60.

A later autopsy cited hypertensive cardiovascular disease and severe arterial blockage. His family blamed decades of inadequate prison medical care. His attorneys hinted at negligence.

Others — darker corners of the city’s rumor mill — whispered assassination.

But coroners said otherwise.

The stress of ruling an empire, losing it, informing on hundreds, and living under permanent threat had finally collected its biological debt.

The irony was suffocating:

His partner, Tony Lewis Sr., walked free at 60.

Rayful died at 60 — less than a year short of freedom.

The Legacy No One Wants to Own

So who was he?

A monster?

A genius?

A product of parental indoctrination?

A Robin Hood with blood on his hands?

A rat?

A reform tool?

The truth — as Washington learned — is that he was all of these things at once.

His empire worsened addiction, violence, and loss.

His organization left families shattered and neighborhoods scarred.

Yet his cooperation solved homicides that once seemed lost to time.

He dismantled cartel-backed pipelines that may otherwise have continued poisoning cities nationwide. His case even forced reform of federal prison telephone systems, changing the way inmates communicate across the U.S.

He was villain and weapon — destroyer and tool.

Even decades later, his name appears in rap lyrics, whispered as a symbol of excess, control, and treachery.

And in the city he once dominated, residents remain split — almost exactly down the middle — on whether justice was ever truly served.

The Best Friend Who Snitched — And the Man Who Snitched Bigger

It began with betrayal.

His childhood best friend Royal Brooks testified against him.

It ended with a bigger betrayal.

Rayful Edmond III snitched on almost everyone else.

More than 300 lives were altered.

Some imprisoned for decades.

Some killed by rival crews after exposure.

Some forced into permanent hiding.

And the boy who once sat at a kitchen table bagging diet pills never lived long enough to be a free man again.

He existed between two worlds — prison walls and confidential informant briefings — until his heart stopped.

The Final Question

In the end, one question lingers over Washington like fog:

If a child is trained to sell drugs by his parents…

If he builds an empire before age 25…

If that empire destroys lives…

And if he then destroys hundreds more through cooperation…

Was he a criminal mastermind — or simply a weapon created too early to ever change course?

Or was he proof that America sometimes builds the very monsters it later condemns?

No jury ever answered that question.

Because his story ended quietly — in a Florida halfway house — 325 days before the finish line.

And that silence may be the loudest part of all.

News

A wealthy doctor laughed at a nurse’s $80K salary backstage. She stayed quiet—until Steve Harvey stepped in and asked. The room went silent. Then Sarah cried—not from shame, but relief. Respect isn’t a title. | HO

Chicago Memorial chose two families from the same institution for a special episode—healthcare workers on national TV, the pitch said,…

On Family Feud, the question was simple: ”What makes you feel appreciated?” She buzzed in first—then her husband literally stepped in front of her to answer. The room went quiet. Steve didn’t joke it off; he stopped the game. The real surprise? Her honest answer finally hit the board. | HO

Steve worked the crowd like he always did. “All right, all right, all right,” he called, voice rolling through the…

He didn’t walk into the mall looking for trouble—just a birthday gift. When chaos hit, he disarmed the shooter and held him down until police arrived. Witnesses begged the officer to listen. Instead, the ”hero” was cuffed… and the cop learned too late | HO

He stayed low, using shelves as cover, closing distance step by silent step. For him, this was a familiar equation:…

Three days after her dream wedding, she learned the unthinkable: her ”husband” already had a wife. | HO

Their marriage didn’t look like the movies. It looked like overtime and budgeting apps and Zoe carrying the weight of…

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud Mid-Taping When Celebrity Did THIS — 50 Million People Watched | HO!!!!

During a short break in gameplay while the board reset, Tiffany decided to “work the crowd,” something celebrity guests often…

She Allowed Her Mother To ‘ROT’ On The Chair And Went To Las Vegas To Party For 2 Weeks | HO!!!!

Veretta raised Kalin with intention: discipline mixed with tenderness. Homemade lunches in brown paper bags. Sunday mornings at Greater Hope…

End of content

No more pages to load