Historians restore a 1901 photograph — and discover what the child was holding on his wrist | HO~

I. The Auction Discovery

The air inside the auction house was thick with the smell of old paper, varnish, and the slow decay of forgotten time.

Rows of glass cases gleamed beneath tired bulbs, each filled with relics of the past — silver spoons, Civil War medals, tattered books, and family portraits whose descendants no longer remembered their names.

Emma Bradford moved among them like someone half in this century, half in another.

A restoration historian and expert in early American photography, she had spent her career rescuing ghosts from the corrosion of silver and glass. Her eyes had been trained to see what most people missed — the faint shimmer beneath a layer of oxidation, the hidden detail in the darkness.

That morning had been ordinary — until she found it.

Nestled in a cracked leather case, tarnished and dull, lay a daguerreotype dated 1901. The auctioneer had dismissed it as “family portrait, condition fair,” and started the bidding at forty dollars. Emma’s pulse had quickened the instant she looked through the glass.

A well-dressed family posed in a park — women in elaborate dresses, men proud in their suits, children neatly arranged like porcelain dolls. But at the edge of the frame, half-hidden and almost out of focus, stood a boy. Barefoot. His clothes torn. His face dirty. And his eyes —

cold.

He stared straight into the camera, defiant, furious, as though the photograph itself had trapped him in a moment of unbearable truth. And in his small clenched hand, he held something — tight, desperate — something the rest of the family either didn’t see or didn’t want to.

Emma bought it without hesitation. Forty dollars for a piece of history — or perhaps, a confession.

II. The Boy in the Photograph

In her Cambridge studio — a converted textile mill flooded with pale morning light — Emma laid the daguerreotype beneath her magnifying lamp.

She had restored hundreds of images from the 19th and early 20th centuries. She’d seen soldiers, mothers, coal miners, sailors. But this one unsettled her.

The contrast was brutal: the polished family and the ragged boy, both frozen in the same frame, both meant to represent Boston’s Gilded Age. But one was clearly there by force of circumstance, not by choice.

The more Emma studied his face, the more she saw. The boy’s cheek bore a bruise, faint but unmistakable. His feet were bare, cut and bruised. And his fist — clenched so tightly that even a century later, the tension showed in the silver grain of the image.

“What are you hiding?” she whispered.

That night, she scanned the image at ultra-high resolution. Line by line, detail by detail, the past began to reveal itself. She enhanced shadows, adjusted contrast, and focused on the boy’s small, pale hand.

Between his fingers, something curved, something faintly organic. Not metal. Not cloth. But bone-white.

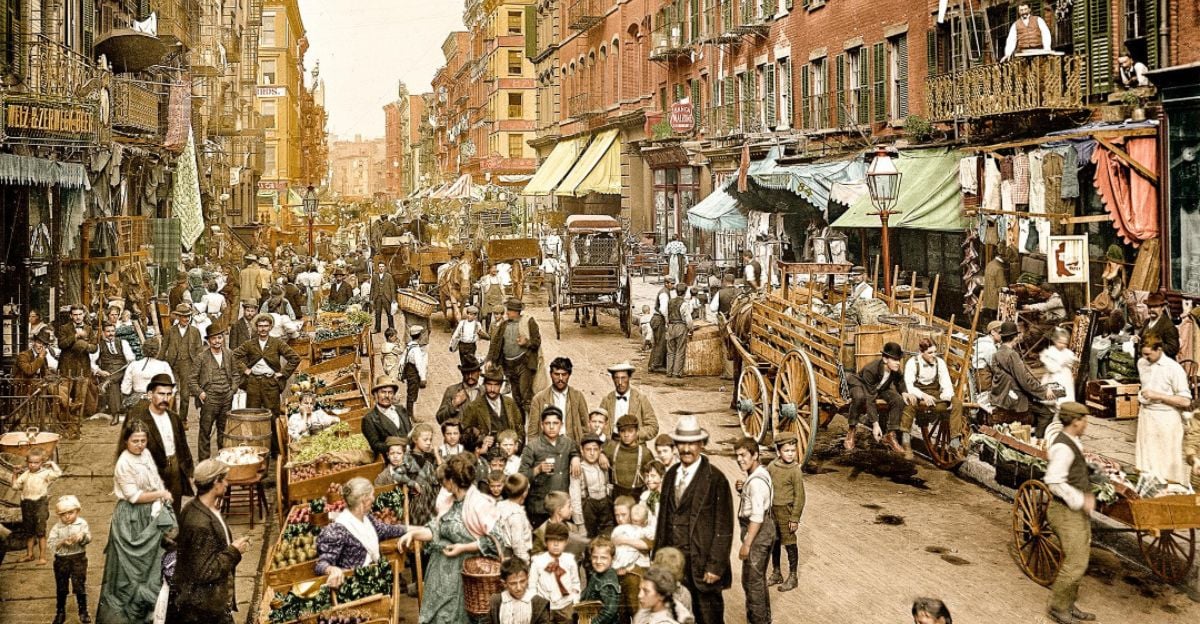

![Class of 1901 group picture [02] | University of Idaho Student Organizations Collection](https://objects.lib.uidaho.edu/pg2/pg2327.jpg)

III. The Restoration Process

Restoring a daguerreotype is not like restoring a painting. It’s surgery. Every movement must be exact. One mistake can erase history forever.

Emma began at dawn. She removed the fragile glass cover, documented the cracks, the oxidation, the corrosion. Using a process called electrolytic reduction, she carefully dissolved the tarnish without harming the silver beneath. Slowly, inch by inch, the image brightened.

What emerged was both exquisite and horrifying.

The patriarch — tall, proud, holding a silver-handled walking stick. The matriarch — calm, composed, her hands folded neatly in her lap. Three children, immaculate in white. And behind them, that barefoot boy, glaring at the lens like he wanted time itself to remember.

When Emma adjusted the light, something new appeared in the background — a red-brick building with limestone trim. She recognized the architecture instantly: Boston’s South End, near Rutland Square. A century ago, that building had belonged to the Boston Children’s Aid Society.

The irony struck her like a blow.

This family had posed for a portrait in front of a charity building meant to protect children — while one stood behind them, neglected, abused, and desperate to be seen.

IV. The Hidden Object

Emma enhanced the boy’s hand once more. This time she used a digital microscope, mapping microscopic light variations invisible to the human eye.

At 200x magnification, the mystery resolved into a shape — small, pale, curved, with what looked like root fibers at one end.

She froze.

It was a tooth.

Human. Adult-sized.

Emma felt her breath catch. For a long moment, the studio was silent except for the hum of her computer. Then she whispered, “Oh my God.”

The boy had been holding a human tooth — someone else’s — with the kind of grip one reserves for proof.

V. The Historian’s Partner

She called Marcus Chen, a historian from Boston University and her longtime collaborator. Marcus specialized in the Gilded Age — the city’s split between wealth and squalor, privilege and exploitation.

He arrived forty minutes later, coffee in one hand, curiosity in the other.

Emma showed him the scan.

Marcus leaned closer. “That’s not just neglect,” he said softly. “That’s a child worker. Look at his clothes — factory wear, not servant’s attire. Torn shirt, heavy stitching.”

“And the tooth?” Emma asked.

Marcus didn’t answer immediately. Instead, he reached into his satchel and pulled out a ledger. “I’ve been studying early mill records from Lowell and Lawrence. Around 1900, children made up nearly a quarter of the workforce in some factories. There were reports — quiet ones — about disappearances, injuries covered up by mill owners.”

“Covered up?”

He nodded grimly. “Boston’s elite didn’t dirty their names with scandals. They paid for silence.”

Emma turned the monitor back toward the boy’s clenched fist. “Then this might not just be a photograph. It might be evidence.”

VI. Tracing the Aldrich Family

At the Boston Public Library, surrounded by brittle ledgers and dust-thick air, they began their search.

Marcus identified the building first: the Children’s Aid Society, demolished in 1968. That placed the photograph near Rutland Square. From there, Emma found the photographer — Edmund Pierce, a well-known studio artist on Tremont Street, specializing in family portraits.

Within hours, Marcus matched a family from the Boston Social Register, 1901:

Harrison P. Aldrich – Textile magnate,

Wife: Catherine,

Children: Margaret (12), Elizabeth (9), Harrison Jr. (7).

Emma compared the listing to the photo. The ages, faces, even the clothing matched.

So the family in the daguerreotype was the Aldrich family — textile royalty.

And the barefoot boy? His name wasn’t listed anywhere.

But in a dusty ledger from the Lowell Mill archives, Marcus found him:

Thomas — child worker, approx. age 8. Employed in picking room. Wage: board only. Accompanied mother (Margaret, deceased July 1900). Transferred to Aldrich household, September 1900.

Transferred.

The word made Emma shiver. Not “hired.” Not “adopted.” Transferred — as if he were property.

VII. The Cover-Up

Among Harrison Aldrich’s private correspondence, filed under Household Expenses 1900–1902, Marcus found a letter.

Dr. Thorne — Regarding the recent incident with the ward Thomas. I trust your discretion. The boy’s injury was accidental and requires no official documentation. Your continued cooperation will be reflected in our arrangement.

Dr. Robert Thorne — a physician listed in the 1901 Boston Medical Directory, specializing in “injuries of a delicate nature.”

Emma felt her stomach turn. “That’s Victorian code,” she said. “It means sexual or physical abuse.”

Marcus found another letter, this one from a concerned colleague to the Massachusetts Medical Board, warning that Thorne was helping wealthy clients conceal crimes. The board dismissed the claim, noting Thorne’s “prominent associations.”

And then, in the Boston Herald society pages, a photograph: Harrison Aldrich and Dr. Thorne, smiling at a charity gala for children.

Emma stared at the clipping in silence.

“The hypocrisy is staggering.”

VIII. The Tooth

Weeks passed in a blur of research, anger, and revelation. Emma and Marcus reconstructed a timeline:

July 1900: Thomas’s mother dies of tuberculosis.

September 1900: Thomas transferred to Aldrich household.

October 1900: Letter references a “ward’s injury.”

March 1901: Thomas dies. Official cause — accidental drowning in the Charles River.

The death certificate listed the person who reported the death: Harrison P. Aldrich.

The police report said the boy had “wandered from the residence.” The body was “released to Mr. Aldrich for private burial.”

No investigation.

No autopsy.

And no mention of a missing tooth.

When Emma examined the restored photo again, she noticed something she had overlooked: bruises across Aldrich’s knuckles, the silver-handled walking stick, and the faint swelling around his jawline.

“Marcus,” she said quietly, pointing at the screen. “He’s missing a tooth.”

Marcus’s expression hardened. “Then Thomas didn’t just hold it as evidence. He tore it from the man who killed him.”

IX. The Grave

They found the grave three weeks later — a small plot in the neglected corner of Boston’s South End Burying Ground. The record read: Christian charity for a departed ward. Paid by H.P. Aldrich.

The site was unmarked, overgrown, forgotten.

Emma stood there, the wind cutting through her coat, feeling the centuries collapse around her.

If the tooth had been buried with him — hidden in his clothing or clenched in death — modern DNA could identify its owner. It could finally prove what that photograph had always known.

They obtained legal permission for exhumation, supported by the district attorney’s office. The state forensic team arrived on a freezing December morning, cameras and gloves in hand. Local reporters gathered at the gates, drawn by the whispers of a “Gilded Age murder.”

When the coffin was lifted from the earth, Emma felt her throat tighten. The wood had long rotted, leaving only fragments, bones, and a few rusted nails.

The forensic anthropologist knelt beside the remains, brushing away the soil with delicate precision.

And then she stopped.

“Emma,” she said quietly. “You need to see this.”

In the crook of the child’s right arm, protected by the curve of his ribs, lay a small, pale object.

A tooth.

Still there.

Still clenched in eternity.

X. Justice, a Century Late

DNA analysis took six weeks.

When the results arrived, the evidence was irrefutable: the tooth belonged to an adult male, genetically matched to surviving Aldrich descendants.

The revelation ignited Boston’s academic and legal circles. The district attorney called it “a case of historical homicide.” Harvard historians dubbed it “a crime preserved in silver.”

But for Emma, the real victory was quieter.

Standing in her studio, the restored daguerreotype before her, she looked again into Thomas’s eyes — the boy who refused to disappear. The boy who stared through time, through privilege, through the silence of history itself.

He had held the truth in his small fist for 123 years.

Now, finally, someone had listened.

Epilogue

The photograph now rests in the collection of the Boston Museum of History, displayed under the title:

“Thomas — The Boy Who Bore Witness.”

Visitors often pause at the image. They see the elegant family first, polished and composed. Then they notice the boy — ragged, defiant, unblinking.

Few realize what he holds.

Fewer still understand the courage it took to hold it.

But Emma Bradford does. Every time she looks at that photograph, she remembers the December wind over the grave, the cold gleam of silver, and the faint whisper of justice long delayed but never denied.

“History,” she tells her students now, “doesn’t forget. It only waits for someone patient enough to look.”

News

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!!

He Planned a Romantic Christmas Getaway – Days Later, He Was Found Under a Bridge in Florida | HO!!!! On…

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!!

Black Girl Brought Breakfast to Old Man Daily — One Day, Military Officers Arrived at Her Door | HO!!!! Aaliyah…

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!!

The neighborhood thought she was a QUIET NEIGHBOR, until police found THIS in her home… | HO!! 23 St.Paul Street….

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!!

A Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy’s Wife in Public — What Bumpy Sent Him Made the ENTIRE Family RETREAT | HO!!!! Bumpy…

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

He Told His Pastor Dad He Is Bringing His Fiancé to See Him, But It Ended in 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!…

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!!

21 Years Old Gold-Digger 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her 71 Years Old Billionaire Husband and Dog for Money | HO!! From a young…

End of content

No more pages to load