“So what’s going on?” an officer asks him.

“So I found him. I think he’s a federal agent,” the man says. Then, correcting himself in real time, he adds the part that actually matters. “Okay. And he got very angry that I was filming him, and he ran up to me. He grabbed me. He threw me on the ground.”

The officer blinks at the phrase like it’s too big to swallow without water. “Are you law enforcement or what?”

“No, no,” the man answers. “Just no federal involvement or anything. Zero.”

Another officer tries again, more specific. “You work for the government or—”

“No.”

A pause. The kind where everybody knows the next minutes are going to decide who’s believed.

“I mean, I don’t know what you want me to—call him from my work,” the man says, frustration rising, because he can feel the drift of the conversation. He can feel it trying to turn him into the problem for holding a phone.

This is where the promise of the night gets made, whether anyone says it out loud or not: somebody’s story is going to get paid back later, in bodycam footage, in reports, in court dates, in headlines. That’s the wager—truth versus tone, evidence versus entitlement—and the station’s bright lights don’t care who loses.

Here’s the part nobody wants to admit in the moment: the camera is not the conflict; the reaction is.

The officers walk the scene like they’re measuring it with their eyes. “You start hollering and all that,” one says to the man from the pump, “this guy’s alleging you toss him on the ground trying to grab his phone out of his hand.”

“Did he get on the ground?” the man shoots back, a little too quick.

“Yeah, he made it,” the officer replies, dry. “Were you on the ground with him?”

“I was on the ground. No,” the man says, catching himself mid-sentence, as if his body remembers something his mouth would rather not. “Okay.”

“Did you get physical with him at all?”

“He was actively resisting,” the man says, reaching for language that sounds official, justified, trained.

The officers don’t let that slide without context. “Was he following you?”

“I didn’t notice him while I was driving. I only saw him when I got out.”

“So you’re pumping gas, minding your own business,” the officer summarizes, “he’s obviously recording you, recording the car, all that stuff. You guys exchanged words or anything like that?”

“Not initially,” the man admits. “Not until I came around the corner and kind of hollered out.”

“Why are you following me?” the officer prompts.

“I was just—okay,” the man says, like the sentence ends in a shrug.

“But you were saying you obviously initiate the contact with him trying to—okay,” the officer replies, and the word “initiate” lands like a paperweight.

A car passes, tires whispering on asphalt. The nozzle clicks again somewhere at another pump, a tiny mechanical sound that feels absurdly calm.

“You’re not injured,” an officer tells the man at the pump. “You don’t need medical attention or anything like that.”

“No,” he says, and then adds quickly, “We didn’t run the car. Just personal car. My personal. I’m not—”

“We’re just here,” the officer cuts in. “We got called here. Understand the seriousness of this and the—” He’s choosing his words carefully, avoiding turning the encounter into a speech. “We have a job to do.”

“I understand,” the man says, but his tone says he doesn’t understand why the job is happening to him.

The other man stands off to the side, phone still in hand, shoulders tense but steady, as if the device is both his evidence and his shield. “I was literally silently filming,” he will later insist. “With my iPhone camera. I said nothing. There were no words that were exchanged.”

And in that gap between “silent” and “hollered,” the night tilts.

A hinged sentence: He didn’t panic because he was being filmed—he panicked because the filming could outlast his authority.

The scuffle, as described, is a blur of intention and outcome. The man from the pump frames it as a single goal: get the phone, delete the picture, end the threat. “Are you saying he fell to the ground when you were trying to grab the phone?” an officer asks, giving him an off-ramp.

“Did you push him to the ground?”

“Well, maybe,” the man concedes, and “maybe” is the sound of a story beginning to crack. “In the struggle. He went down, but with the sole intention of grabbing the phone to delete the pictures.”

The officers glance toward the far corner of the lot, toward a rock near the sidewalk, toward the place where the pavement looks no different than any other place you could trip, stumble, or be driven down onto. One officer asks, “Where are you guys rolling around at?”

“Right over there by that rock,” someone answers.

“How’d you guys get separated? Do you remember?”

“I guess I got stood up,” the man says. “I guess, you know, and started hollering.”

“So you didn’t punch him or anything like that?” an officer asks.

The question is simple, but it carries a warning: we are not here for your pride; we are here for what you did.

In the moment, the man at the pump tries to make himself sound like the one who was violated. “He’s filming me while I’m trying to pump my gas. He’s got the camera on my face,” he says earlier. “I don’t want anybody sticking their camera in my face. I don’t know what he’s trying to do with this.”

The other man’s version doesn’t need embellishment. He stays with the physical facts. “He ran up to me,” he says. “He grabbed me. He threw me on the ground. He tried to grab the phone out of me.”

The officers listen, then do what local police do when the story is louder than the proof: they go hunting for proof. They look at the angle of the sidewalk. They ask who saw what. They collect names from people who honked, who yelled, who slowed down long enough to intervene and then drove away when it felt safe again.

The gas pump nozzle sits there, the way an object sits when humans turn it into a prop. A handle meant to dispense fuel, now dispensing something else: motive, justification, an excuse to say, I was just trying to finish what I came here to do.

Later, the story travels—out of the parking lot, into reporting, into public view—because this wasn’t just a random “guy at the pump” moment. The name drops. The roles harden. And suddenly it isn’t simply two men and a phone; it’s a local police department making a call about a federal agent’s conduct in their jurisdiction.

Kudos get given where they’re due, because the details don’t float up on their own. A report makes it into print. Bodycam audio surfaces. And the cozy narrative—hero agent targeted by agitator—starts to look less like truth and more like choreography.

A hinged sentence: When the camera stays on, the mask doesn’t get to.

According to reporting that cites obtained bodycam footage, one officer is heard saying, bluntly, “Don’t look good. [He] grabbed at him. [He] gets him on the [expletive] ground.” It’s not polished language; it’s the kind of spontaneous assessment that happens when someone’s trying to reconcile a badge-shaped story with what the footage suggests.

And then there’s the other case threaded into the same public conversation, the one that raises the temperature even more: an off-duty officer who admitted to shoving a 68-year-old man to the ground because he was being filmed. That number—68—lands like a brick because it isn’t an abstraction. It’s a body. It’s bone density. It’s the line between “uncomfortable” and “dangerous.”

The man who was pushed, Gregory Bovino, is confronted later in a scene that plays like a reckoning performed at conversational distance. “Gregory Bovino, I’m looking at you,” the voice says. “Do you have anything to say to me? That’s the question you asked me when you arrested me. You wanted to know if I had anything to say to you. I’m asking you the same question.”

The confrontation keeps going, a string of accusations and warnings: “You arrested me on September 27th. That was illegal. Unconstitutional. Dangerous.” A reference to touching a car, to someone’s personal space, to a threat of “consequences.” And then, the kicker meant to make the point immovable: “Four federal judges. Four federal judges have found your conduct unconstitutional.”

Four. Not one judge on a bad day. Not a single outlier. Four decisions that, in plain language, say: you didn’t get to do that.

“Leave Chicago,” the voice says. “You losers, get out!” It’s anger, yes, but it’s also the frustration of someone who feels the system only corrects itself after the damage is done.

All of it swirls back to the gas station story because the theme is the same: someone with power, or proximity to it, reacting poorly to being documented—and then trying to flip the script.

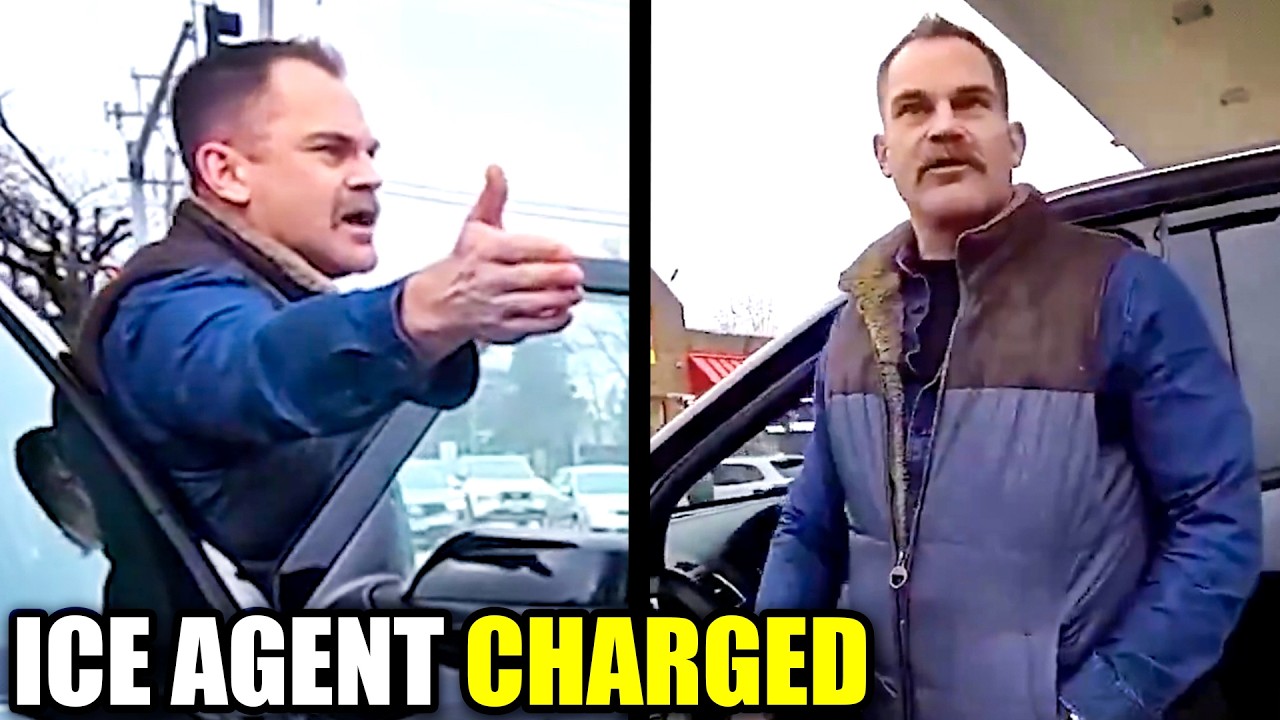

Back at the center of this particular storm is a name: Adam Scirocco, a United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent. The update is specific, and that specificity is what makes it so rare. Scirocco was charged with misdemeanor battery—local authorities taking an enforcement action against a federal agent, the kind of thing that usually gets smoothed over, redirected, or buried under layers of “we’ll handle it internally.”

A hinged sentence: The rarest sound in American bureaucracy is accountability clearing its throat.

The reporting continues, adding a timeline and a second set of quotes that sharpen the edges. An attorney, Robert Held—described as both lawyer and activist—told The New York Times he followed Scirocco in late December after the agent left an ICE facility in Broadview, Illinois. “Followed” is the word that makes half the audience recoil and the other half nod, because it can mean anything from stalking to simply driving behind someone on the same road and then recording in public. That ambiguity is where narratives breed.

Scirocco, according to police, initially denied being law enforcement. Later, he told officers called to the scene that Held began walking up to his vehicle and recording him on his phone while he was pumping gas.

Held disputes the framing. “I was literally silently filming, with my iPhone camera,” he says. “I said nothing, there were no words that were exchanged.” He describes the first physical contact as coming from Scirocco, not from him. “He was like, grabbing onto my iPhone. He was on top of me. I was on the sidewalk on my back or side and he… and I said, calm down, you need to de-escalate.”

The phrase “you need to de-escalate” is almost comical in its role reversal—one man pinned down, still trying to talk like the training manuals he wishes the other person had read.

Held says cars honked. People yelled. Strangers stopped, not out of curiosity but out of that instinct that says: this could turn into something worse if no one witnesses it. “It was all a little bit of a blur,” he admits, “but the best news— I was uninjured.”

Investigators did what investigators are supposed to do when there’s heat and politics and a federal badge lurking in the background: they looked at footage and talked to witnesses. After reviewing camera footage and speaking with witnesses, they determined the encounter occurred at the far corner of the parking lot near the public sidewalk—exactly the kind of detail that matters, because “public sidewalk” is legal oxygen for recording.

And then another detail: Scirocco didn’t dispute that he initiated physical contact. That’s not a moral judgment; that’s a factual hinge. Once you start the physical part, you own the consequences of it, especially when the other person’s alleged “provocation” is a phone held at chest level.

Held describes meeting with the prosecutor and the detective, careful to credit the institutions rather than make it about personal victory. “The hard work was all done by the police and the state’s attorney’s office,” he says. “The ball’s in their court. Individuals obviously don’t prosecute criminal cases. That’s up to the state’s attorney. So they’re bringing the case.”

The court date looms: March. Scirocco, at the time of the update, hadn’t entered a plea.

A hinged sentence: March isn’t a month on a calendar—it’s a deadline for the story you told in December.

Then the federal layer arrives, like it always does—polished statements, official titles, and language built to reverse the burden of proof. The Department of Homeland Security issues a statement two days later and describes Held as a “known ICE agitator.” The words are chosen like a shield: “known,” implying a file; “agitator,” implying disorder; “ICE,” implying the right to frame the entire situation as a security issue.

DHS claims Held targeted and aggressively harassed the agent, and that the agent acted to protect himself when faced with threatening behavior. In that telling, the phone becomes a threat, the recording becomes “doxing,” and the man who put hands on someone becomes the one needing protection.

Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin is quoted saying these were clear attempts to dox “our officer.” The phrase “our officer” is doing two jobs: it claims ownership, and it tries to wrap the individual’s conduct in the flag of the institution. She adds that the officer was alone and without protective equipment, and acted to protect himself.

But there’s a reason people don’t just read the statement and move on, and it’s not because everyone has suddenly become a legal scholar. It’s because the words run into the physics of video. And because the public has gotten familiar with the move: make the documentation sound like danger; make the reaction sound like defense.

The conversation widens to include reporting on finances and influence. ProPublica is cited regarding political ties—“no firm has closer ties” to Kristi Noem’s political operation than the Strategy Group, which played a central role in her 2022 South Dakota gubernatorial campaign. Corey Lewandowski is mentioned as a top advisor at DHS with extensive ties to the firm. And the CEO’s marriage to McLaughlin is pointed out as part of the web.

It’s the kind of detail that doesn’t prove what happened at the gas station—but it does explain why so many people distrust the framing coming from the top. When the institution defending the agent also looks like it’s defending its own network, every word in the statement starts to feel like a strategy memo.

A hinged sentence: When your press release sounds like it was written by your donor list, people stop hearing it as truth.

The narrator voice in the original commentary makes a point that’s less about this one parking lot and more about a broader pattern: “I want to be clear about something,” the voice says. “I have not seen this attorney and activist outside of Broadview. I have gone many times.” He describes Held as known among community members not only for speaking out but for representing clients—suggesting this isn’t random harassment but part of a public-facing conflict around a facility and its operations.

Then comes the claim that cuts to motive: the agent’s temperament, the fragility, the likelihood that the physical contact happened because being recorded felt intolerable. “If he was on a public sidewalk and this ICE agent… went up to him and likely [got physical], then there will be, I believe, some form of justice here.”

The argument goes one level deeper: they hide because they know it’s unpopular. They obscure identities because they don’t want to be known. Not because they’re shy—because visibility has consequences now. Because the public is no longer willing to accept “trust me” as a substitute for “show me.”

Back at the gas station, the officers are still working with what they can touch: the location, the witnesses, the footage. Their tone in the bodycam clips is telling—less reverence, more assessment. They aren’t starstruck by “federal.” They aren’t treating “I’m a federal agent” like it’s a magic phrase that turns a shove into policy.

In the first man’s mouth, “federal agent” is both a claim and a complaint. In the second man’s mouth, “federal agent” is a question that got answered with hands. And in the officers’ mouths, “federal agent” is just another detail that doesn’t change the math of who initiated contact.

Somewhere in the middle of the lot, the gas pump nozzle returns to view—the same ordinary object, now loaded with meaning. Early on it was the reason for the encounter: “I’m just trying to pump my gas.” Later it becomes the backdrop for the evidence: the far corner, the public sidewalk, the footage reviewed, the witness statements. And by the end, it becomes a symbol of the whole mess: a routine act turned volatile when someone decided their image was private even while standing in public.

A hinged sentence: The nozzle didn’t start the fight, but it became the excuse.

The payoff isn’t a dramatic takedown or a viral one-liner. It’s paperwork. It’s a misdemeanor charge filed anyway. It’s local authorities refusing to pretend they didn’t see what they saw. It’s a court date in March where the story has to survive questions, not applause.

And it’s the aftertaste that lingers, because the DHS statement doesn’t just defend one person—it signals a posture. “We won’t accept this,” it says, meaning: we won’t accept being recorded, being identified, being held in public view. But that’s not really a choice anyone gets to make on a sidewalk.

If you zoom out, the night at the pump is a tiny stage for a bigger American argument: what happens when people who exercise state power are treated like they’re above the social contract that comes with it. When a person with authority, formal or informal, decides that accountability is harassment. When “delete that” becomes the instinct instead of “explain this.”

Held’s account emphasizes the mundanity of his own behavior—silent filming, no exchanged words—because he knows how quickly “activist” can be used like a slur. Scirocco’s account emphasizes the intrusion—camera in the face, license plate captured—because he knows how quickly “doxing” can turn the public against a filmer. And the police, caught between those competing frames, do the only honest thing available: they treat it like a local incident with local consequences, and they follow the evidence.

By the end of the clip, the narrator asks viewers to stay tuned, to follow along, to support the channel. The modern coda to every public incident is the same: attention is currency, and the story will keep paying out as long as people keep watching.

But the real coda is quieter. It’s the memory of how fast “I’m just pumping gas” turned into “I need to delete your footage.” It’s the fact that a 68-year-old man’s age can become a headline because somebody couldn’t tolerate being filmed. It’s the fact that four federal judges can call conduct unconstitutional and still, on some random night, another person in another parking lot might try the same move.

The gas pump nozzle hangs there again, back in its cradle, like it wants to go back to being nothing. And maybe that’s the point: the objects stay ordinary, but the choices don’t.

A hinged sentence: In America, the camera doesn’t create accountability—it just reveals who can’t live with it.

News

Garbage Workers Hear Noise Inside a Trash Bag, He Turns Pale When He Sees What It Is | HO!!

Garbage Workers Hear Noise Inside a Trash Bag, He Turns Pale When He Sees What It Is | HO!! The…

The Appalachian Revenge K!lling: The Harlow Clan Who Hunted 10 Lawmen After the Still Raid | HO!!

The Appalachian Revenge K!lling: The Harlow Clan Who Hunted 10 Lawmen After the Still Raid | HO!! The motive wasn’t…

50 Cent Saves Girl From An Orphanage & She Breaks Down In TEARS After She Meets & Thanks Him | HO!!

50 Cent Saves Girl From An Orphanage & She Breaks Down In TEARS After She Meets & Thanks Him |…

Rich man gives a luxury car to a kind hearted construction worker, his reaction made us cry 😭 | HO!!

Rich man gives a luxury car to a kind hearted construction worker, his reaction made us cry 😭 | HO!!…

The Illinois Barn 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬: 14 Hired Hands 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐀𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐞 Over Destroyed Corn Fields | HO!!

The Illinois Barn 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬: 14 Hired Hands 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐀𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐞 Over Destroyed Corn Fields | HO!! James Edward Henley, 48, was…

‘His Name Was Bélizaire’: Rare Portrait of Enslaved Child Arrives at the Met | HO!!!!

‘His Name Was Bélizaire’: Rare Portrait of Enslaved Child Arrives at the Met | HO!!!! “The fact that the boy…

End of content

No more pages to load