‘I’m Done.’ The Phone Call That Ended Charles Schulz ‘Peanuts’ in One Night | HO

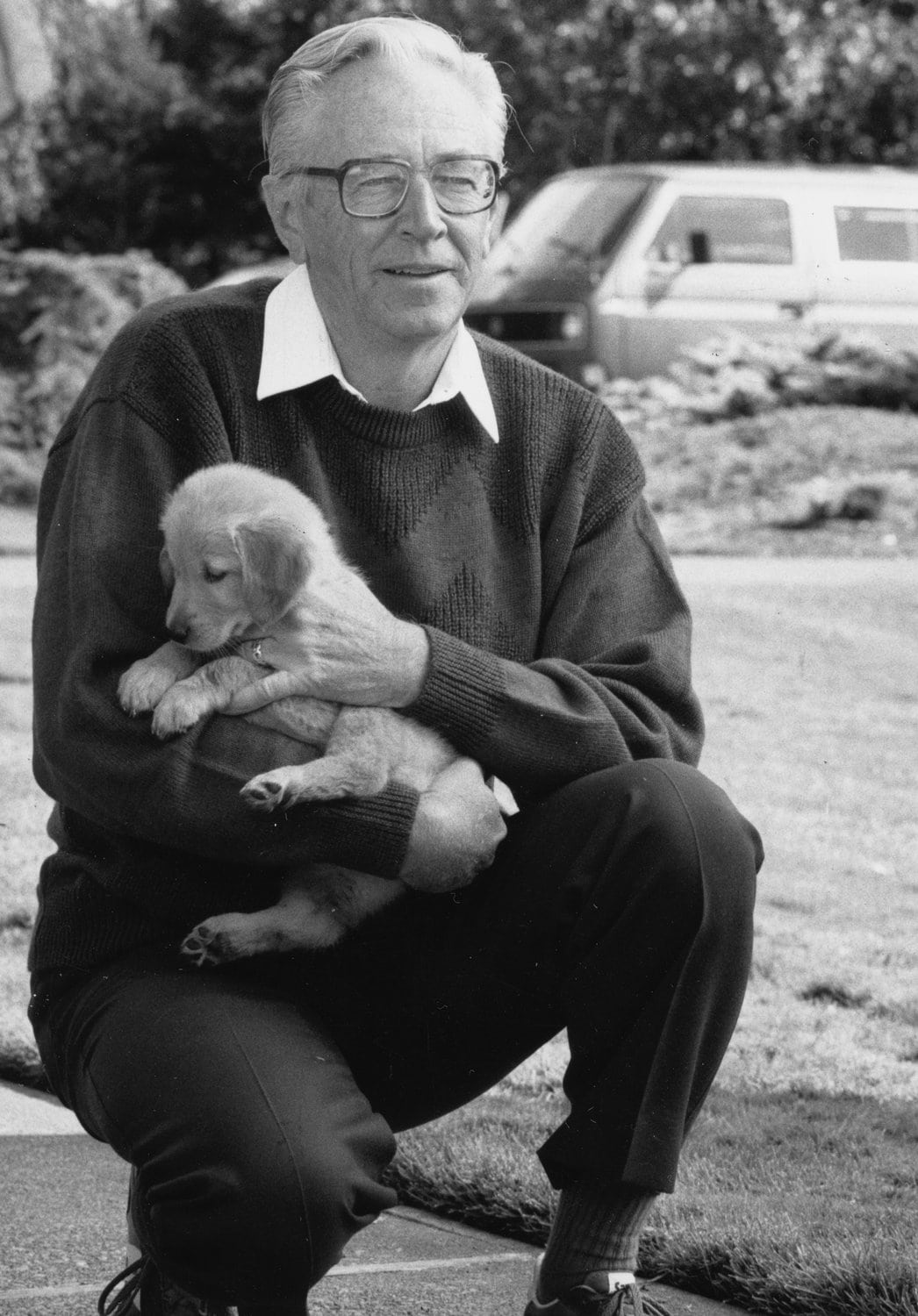

For half a century, Charles Schulz sat at his drawing board, quietly shaping the world of Peanuts. Day after day, year after year, he never missed a deadline, never let a single strip go unwritten.

The boy who once felt invisible in his own classroom became the most recognizable cartoonist on earth. But in December 1999, everything changed with a single phone call—a moment that ended Peanuts forever and left millions of fans stunned.

The story of how Schulz’s life and legacy came to a sudden, heartbreaking halt is one of quiet heroism, private pain, and the kind of creative devotion rarely seen in any field. As the world mourned the loss of Charlie Brown’s creator, the truth emerged: for months, Schulz had been hiding a devastating secret, and the final decision to step away from his beloved strip would be the hardest he ever made.

A Childhood Shaped By Loss and Loneliness

Charles Monroe Schulz was born on November 26, 1922, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His father, Carl, a barber of German descent, and his mother, Dena, a Norwegian waitress-turned-homemaker, struggled to make ends meet during the Great Depression.

For two years, the family moved to Needles, California, where Schulz’s sense of insecurity and fear of losing everything took root—feelings that would later echo in the small worries and quiet sadness of his Peanuts characters.

Nicknamed “Sparky” just days after birth, after a popular comic strip horse, Schulz seemed destined for a life in cartoons. But his early years were marked by loneliness. Bullied and out of place at school, he was skipped ahead two grades, making him smaller and younger than his classmates. The pain of being left out followed him into adulthood and became the emotional core of Charlie Brown—the perpetual outsider.

Schulz’s only solace was his dog, Spike, a black and white mutt with a talent for eating nails and tacks. Schulz’s first published drawing, a sketch of Spike, appeared in Ripley’s Believe It or Not in 1937. The joy of seeing his work in print was short-lived, as classmates mocked him and teachers ignored his achievement. The lesson was clear: success didn’t guarantee acceptance.

Art, Grief, and the Birth of Peanuts

Schulz’s mother was his greatest supporter, buying him art supplies even when the family could barely afford food. But in 1943, she died of cervical cancer at just 48—days before Schulz was drafted into the army. Her death haunted him, and every comic he drew carried a piece of her inside.

After serving as a staff sergeant in the 20th Armored Division during World War II, Schulz returned home, broken by grief and trauma. He took a job grading art for a correspondence school, earning little but learning the craft that would carry him through life. Co-workers became inspirations for future Peanuts characters, including the elusive “little red-haired girl,” modeled after Donna May Johnson, a woman Schulz loved and lost.

Schulz’s first comic strip, Li’l Folks, ran from 1947 to 1950 in local newspapers. When editors refused to move it to the comics page or raise his pay, Schulz was forced to quit. Undeterred, he pitched his idea to United Feature Syndicate. They rejected his preferred titles, instead calling the strip “Peanuts”—a name Schulz hated until his dying day.

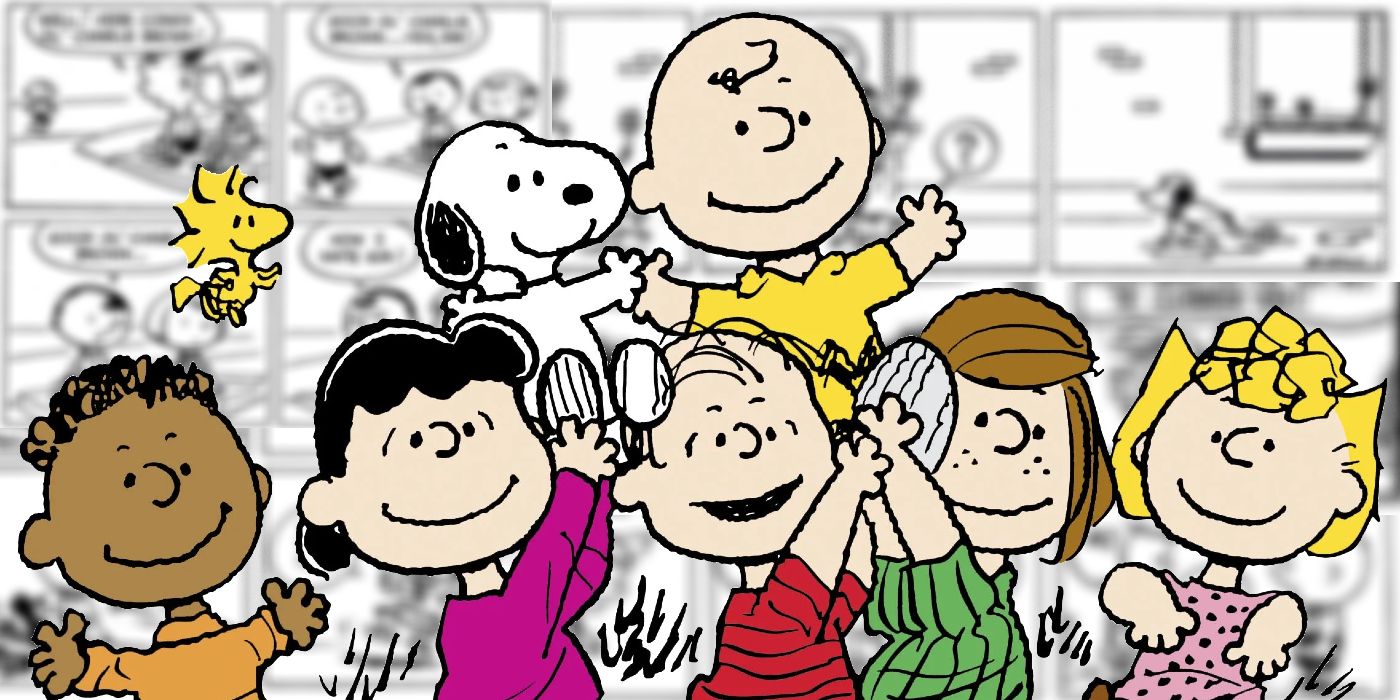

On October 2, 1950, the first Peanuts strip appeared in seven newspapers. Schulz earned just $90 that month, barely enough to survive. But by 1952, Peanuts was in 40 papers, and the cast began to grow. Linus debuted as a baby, eventually becoming the strip’s voice of reason. Snoopy, inspired by Spike, joined two days after the launch, evolving from a silent dog to a global icon.

Building an Empire—and Guarding Its Heart

With Peanuts’ growing popularity, Schulz’s life changed dramatically. By 1955, the strip ran in over 100 newspapers. Lucy’s psychiatric booth appeared, inspired by Schulz’s own therapy sessions after the war. In 1968, Schulz introduced Franklin Armstrong, the first black character in Peanuts, just days after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Southern editors protested, but Schulz refused to remove Franklin, declaring he’d rather quit than erase the character.

Merchandising exploded. Snoopy dolls, Hallmark cards, and books like “Happiness is a Warm Puppy” turned Peanuts into a billion-dollar empire. By the 1990s, the brand released 20,000 new products each year, earning Schulz $30–$40 million annually. He became one of the world’s richest and most successful cartoonists.

But behind the scenes, Schulz battled exhaustion and perfectionism. He drew every strip by hand, sometimes holding his wrist to steady his shaking hand. He took only one five-week vacation in fifty years. Offers poured in from around the world, but Schulz refused to let anyone change his characters. When studios wanted to make Snoopy more human or Charlie Brown more assertive, Schulz said no—even if it cost him millions.

The Pressure Mounts—and the Walls Close In

Despite his success, Schulz never felt truly safe. The wounds of childhood, war, and personal heartbreak lingered. In the 1970s, he fought with United Feature Syndicate over creative control. They secretly hired Superman artist Al Plastino to draw backup Peanuts strips, fearing Schulz would quit. When Schulz discovered the deception, he negotiated a contract guaranteeing only he could draw Peanuts—a victory that came at a steep emotional cost.

Legal battles followed. Accusations of plagiarism and lawsuits over Woodstock, Snoopy’s bird friend, tested Schulz’s resolve. He fought back, winning every case but losing time, money, and peace of mind. In 1981, Schulz underwent quadruple bypass surgery. For the first time in three decades, he stopped drawing. Bootleg Peanuts strips appeared in hundreds of papers, prompting an FBI investigation and arrests across six states.

The hand tremors worsened. By the late 1990s, Peanuts was in fewer newspapers, and Schulz was tired. Rumors spread that the syndicate was seeking replacements. Schulz took his first vacation, and old strips were reprinted. He signed a new deal in 1998, ensuring no one else would ever draw Peanuts.

The Call That Ended It All

On November 16, 1999, Schulz underwent emergency surgery for a blocked artery. Doctors discovered stage three colon cancer that had already spread. Multiple strokes followed, leaving him blind in one eye and unable to draw. Chemotherapy sapped his strength, and by December, Schulz knew he had to retire.

The phone call came late one evening. Schulz, sitting in his studio, broke down in tears. “It’s over,” he told his family. The man who had drawn 17,897 strips over fifty years was finished—not by choice, but by fate. His son Monty later said Schulz’s spirit was broken when he could no longer draw.

On December 14, 1999, Schulz announced his retirement on the Today Show, crying as he told Al Roker, “I never dreamed that this was what would happen to me. But all of a sudden, it’s gone. It’s been taken away from me. I did not take this away from me.” The moment was raw, honest, and deeply human—a final echo of Charlie Brown’s eternal struggle.

Before stepping away, Schulz made one last demand: Peanuts would end with him. No one else could continue the strip. The syndicate was stunned. Most comics outlived their creators, but Schulz insisted Peanuts die with him. Newspapers worldwide agreed to run reruns rather than let another artist touch his work.

A Farewell Letter to the World

Despite his illness, Schulz remained active. On February 11, 2000, he went ice skating with his daughter—just one day before he died peacefully in his sleep at age 77. The next morning, his final Sunday strip appeared in newspapers around the globe. In it, Snoopy sat at his typewriter, writing “Dear friends,” and thanking readers for their support. The timing was uncanny, as if Schulz had planned his goodbye down to the last frame.

At the time of his death, Peanuts was printed in 2,600 newspapers across 75 countries and 21 languages, reaching 355 million readers daily. Schulz’s legacy was secure, but controversy soon followed. A 2007 biography painted him as depressed and distant, claims his family fiercely disputed. The debate over Schulz’s private life continues, but for most, his work remains a source of comfort and joy.

The Charles Schulz Museum, opened in 2002 in Santa Rosa, California, houses nearly 7,000 original strips. It stands as a testament to a man who gave voice to quiet kids everywhere and proved that simple drawings could hold profound meaning.

The End of an Era

Charles Schulz was not a perfect man. He was shy, anxious, and haunted by loss. But he created something extraordinary—an entire universe where failure was met with hope, loneliness with friendship, and every day brought a chance to try again. When he died, it felt like the end of an era.

The phone call that ended Peanuts in one night was more than a retirement announcement. It was the final chapter of a lifelong story—one of perseverance, heartbreak, and quiet triumph. Schulz’s legacy endures, not just in reruns, books, and merchandise, but in the hearts of readers who see themselves in Charlie Brown, Snoopy, and the rest of the Peanuts gang.

As Snoopy wrote in that final strip: “Dear friends, thank you.” And from the world, the answer remains: Thank you, Sparky.

News

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO”

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO” It…

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He Kil.. | HO”

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He…

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You | HO”

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You |…

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO”

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO” Her…

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO”

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO” A…

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

End of content

No more pages to load