”I’M SCARED! I’M SCARED!” — Neighbor Finds Woman 𝐋𝐨𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐝 In Kennel | HO

Here is the hinged sentence that snaps the whole thing into place: the scariest problems don’t arrive with sirens, they arrive with a fence tall enough to make you doubt your own ears.

Justin walks toward the property line and calls out, “Is everything okay over there?” No answer. The screaming continues, steady as a metronome. He stays outside the fence, on the road, where he’s allowed to be, and keeps filming because he doesn’t know what else to do with his hands. Then the police arrive.

An officer steps out, listens, and you can see it in his posture—the instant shift from “routine call” to “something’s wrong.” The fence is tall, and the officer tries to look over it, then looks at Justin like, can you help me see? Justin offers his phone, that same flashlight beam now doing a different job, not comfort but clarity. He reaches his arm up and over the top, not stepping onto the property, not climbing, just angling the camera to catch what’s happening on the other side.

Later, Justin will describe what he saw in quick, clipped phrases, like his brain is trying to protect him by keeping it technical: a tarped kennel in the backyard; someone inside; something being thrown at a vented door; movement; then, when he zoomed in on the video, what looked like chains.

The officer sees enough to say, “That ain’t right,” and immediately backs his truck around to the alleyway so he can get eyes on the kennel from the rear fence. That’s when the five-minute video starts—the one that made an investigative reporter with three decades of experience admit she had a visceral reaction she wasn’t prepared for.

Justin’s voice on the video is raw, incredulous, furious in a way that keeps tripping over itself. “You locked your kid in a dog kennel,” he says.

And Candy Thompson answers like she’s explaining a messy kitchen. “Yes, because she’s tearing up everything.”

Justin can’t believe he’s hearing it. “You really think locking a kid—into a special needs kid? A special needs kid—locking her in a dog kennel?”

Candy shrugs, arms crossed, unfazed. It looks, to some viewers, like a smirk. It looks, to others, like boredom. It looks, in the most honest way, like someone treating another human as an inconvenience to be stored.

Inside the kennel, a voice cracks apart. “I’m scared,” she cries. “I’m scared.” The word “scared” lands again and again, as if saying it might summon the thing that makes it stop.

Justin tries to anchor her with his own voice, loud enough to carry over the fence. “It’s okay, sweetie. It is okay. We got you help. All right. What’s your name?”

“Emily,” the voice answers.

“I’m Justin,” he says. “Okay? Emily, it’s going to be okay.”

The hinged sentence comes in like a door slamming: when a grown-up says “it’s okay” to a terrified person they can’t reach, it isn’t reassurance—it’s a vow.

Justin keeps talking because silence feels like abandonment. He tells her to breathe. He tells her help is there. He tells her to look behind her because there’s a police officer. Emily keeps repeating the same needs like a looped alarm: “I have to pee,” “I’m scared,” “Let me out.” The banging continues, metal clattering in the dark, the kind of sound you can’t unhear once you know what it is.

Candy stays near the scene, still defensive, still justifying. “I’m going to put this dog in there,” she says at one point, as if the kennel is simply a container and the only debate is what belongs inside it. In the backyard, dogs run around freely. They aren’t tied up. They aren’t confined.

The kennel, a police chief later explains, appears clean and is surrounded by tarps with a chair inside, and it doesn’t even look like where the animals usually stay. Which makes the logic collapse in your hands: the animals are free to roam, but the vulnerable adult is the one locked behind a cable-latched door.

Justin, voice breaking with anger he’s trying to keep from turning reckless, confronts Candy again. “Do you understand how bad it is—on a special needs kid—to where I get home and I hear somebody screaming like that? Look at your face. You hear that precious child? I know you have more than just her that’s special needs. And I can hear you calling them that word. And locking them in a freaking dog kennel. Are you serious?”

Emily’s fear spikes. “I’m scared,” she repeats, louder now, like the cold has climbed into her lungs.

Justin answers her with steadiness he had to build in real time. “I know, Emily. I know. Just breathe. Help is here.”

He asks, “What are you scared of, Emily?”

And the answer is obvious in a way that hurts: she’s scared of the thing she’s trapped inside, and the person who put her there, and the fact that it happened enough times to feel normal.

A reporter later points out another detail you might miss in the darkness: Candy’s shirt. The words read like a joke that curdles in your mouth—“I’m one of those crazy people.” Another irony sits right there on the map: Candy lives on Liberty Way.

Hinged sentence, because sometimes irony is just cruelty wearing a grin: when the street is named Liberty and the backyard holds a cage, you realize how cheap a word can become.

Justin will tell the reporter he had one thought when he saw what was happening: keep recording. “That way nothing can be hearsay,” he says. “Everything is shown. That’s evidence.” His voice isn’t proud when he says it. It’s practical, like he’s describing how to hold pressure on a wound. He also says he tried to keep Emily calm, because in that moment, with a fence between them, his voice was the only hand he could offer.

The officer, after seeing the phone footage, moves fast. His face says it before his mouth does: it’s go time. He drives around, positions himself by the alley, and speaks directly toward the kennel. “Police department,” he calls. “What’s going on? We’re about to get you out of here.”

Justin coaches from the other side. “If you look behind you, Emily, there’s a police officer. Okay? Tell him what you just told me.”

Emily’s voice shakes. “I’m scared.”

“It’s okay,” Justin insists, as if saying it enough will stitch her back together. “We’re here now. Breathe. Come on out, sweetheart. Come on out.”

That’s when Candy appears—coming out from inside the home, walking into view like she’s stepping into an argument she didn’t ask for, not a crisis she caused. The officer tells her to stop, to not come closer. He tries to assess what’s happening, tries to keep control of the scene, tries to handle the backyard without hopping the fence. Justin stays where he is, recording, eyes fixed on Emily because he refuses to let her be unseen again.

On the video, you hear banging at the front door. “They’re banging on your door,” someone says. Emily cries, “Okay, I’m scared.” Justin answers, “No, no, no, go get them. It’s okay, sweetheart.” Everything is happening at once—the officer trying to access the property, Candy talking as if inconvenience is her primary injury, Emily pleading from inside a confined space in the cold.

Justin’s anger keeps breaking through. “You have no remorse,” he tells Candy. “You’re the mother. You’re the caretaker. You’re supposed to be somebody that loves and helps and guides, not somebody who gets so frustrated that you lock them in a cage.”

Candy offers her explanation again: “She’s been peeing and tearing things up in the house.”

Justin’s mind catches on one detail that doesn’t add up. “But why is she peeing in the house,” he asks, “when she’s screaming that she has to pee in there?”

It’s a simple question, the kind that exposes a larger truth: this wasn’t a solution; it was control. And control doesn’t care whether it makes sense.

The reporter, Ann Emerson, later says she’s seen horrible things in thirty years and still wasn’t ready for the reaction she had watching the five-minute clip. She interviews Justin and asks him to walk through the night step by step. He tells her he’d heard “a few things” before—yelling, arguments, noises you could dismiss because you couldn’t see them and didn’t know if it was teenagers, or a couple fighting, or a bad TV turned up too loud.

He says that the moment he said, “I’ve heard you many times before,” it clicked in his head that something hadn’t been right for a while. He says he wishes he would’ve called earlier, even for a welfare check, even just to have someone show up and look. Because now he knows what those muffled sounds could have been.

Hinged sentence, because regret is its own kind of evidence: the first sign something is wrong is often the moment you realize you’ve been normalizing the warning noises.

The interview expands the frame. Ann reads details from local reporting: the kennel area appeared clean, surrounded by tarps, with a chair inside; there were animals in the residence; the dogs in the yard weren’t confined. Ann asks what it looked like when the officer finally saw what Justin’s phone captured. Justin says the officer’s face changed instantly, like a switch flipped from “listen and assess” to “act now.”

Ann asks what Justin did during those minutes. Justin says he stayed where he was allowed to be, kept recording, and focused on Emily. “Hey, baby,” he tells her in the clip. “Breathe. Just breathe. Help is here. I know it’s cold, but breathe.”

He says he didn’t know if it was illegal to hop the fence, and he wasn’t going to make a bad situation worse. So he stayed put, phone up, and made sure Emily heard a steady voice through the dark.

Emily, when Justin asks her age, answers clearly: “I’m 22.”

That number changes the way the air feels. Not a little child. A 22-year-old vulnerable adult. Someone who should be able to walk to a bathroom without asking permission, someone who should be able to say “I’m scared” and have it mean something to the people responsible for her care.

Ann asks Justin what he thought when he heard Candy’s justifications. Justin says he was furious, but there was “something over him” keeping him calm and collected, like his body understood that rage without control wouldn’t help Emily. He says he felt furious and sad at the same time. How could someone sit there, with no emotion, no remorse, and act like this was okay? How could someone look at a person locked behind a cable and ask, “What’s wrong, Emily?” like it’s a mystery?

Then comes another detail that makes the story heavier without needing to be dramatic: Candy’s husband, neighbors say, was once the police chief. Justin tells Ann someone even warned him, “It won’t do any good, Justin, because her husband had been the police chief.” Justin doesn’t accept that as an excuse to do nothing.

He says he doesn’t believe behavior like this just starts out of nowhere after a spouse passes away. He says people lose loved ones all the time and don’t suddenly start acting out like that. He wonders if things were hushed up, if that tall solid fence went up for a reason, how often Emily or others were put in that kennel, what else might have happened behind closed doors.

And that’s the moment the story stops being only about one night and becomes about the spaces communities leave uninspected. The story becomes about how authority can cast a shadow long after it’s gone. It becomes about how easy it is to let a reputation do the work of oversight.

Hinged sentence, and it’s a bitter one: the most dangerous cover isn’t darkness—it’s the assumption that “people like that” couldn’t possibly do something like this.

Justin says he doesn’t watch the videos anymore. He says they sadden him and frustrate him. But he keeps talking to anyone who will listen because he wants Emily’s story to be heard, and he wants justice not just for her but for anyone else in that household. He says the experience changed how he moves through the world.

He tells Ann he’s trying to be more aware, to listen more, to keep an ear and eye out without being “too nosy,” to speak up faster when something sounds wrong. He says it made him think about kindness in a way that has edges now—kindness that isn’t passive, kindness that calls 911 when it needs to.

Ann asks if he’s heard from Emily since. Justin says no, and he wishes he could see her. He says he hopes she knows there are thousands of people thinking about her, praying for her, hoping she’s okay. He says he hopes she’s dealing with the aftermath in a good way, whatever that looks like after a lifetime of being made small.

Ann asks Justin his age. “I’m 24,” he says.

Twenty-four years old, two kids at home, twin boys on the way. Ann tells him he’s wise beyond his years. Justin doesn’t bask in it. He talks about his family and says he can’t imagine something like this happening to his children. He doesn’t want to even go down that road in his mind. He says he would do what anybody else would do—except we already know not everybody does.

A neighbor voice appears in the story, saying they’re glad Justin stepped up, saying they hope Candy “gets what’s coming,” framing it in faith and morality. The tone shifts from shock to accountability. And then the legal system enters with the cold language of charges: aggravated kidnapping; injury to a disabled individual; unlawful restraint of a disabled individual; endangering a disabled individual; assault. The report states Candy Thompson and her husband adopted Emily when she was two years old. It also states there were two other vulnerable adults in her care—foster adults—one 34, the other around 27, and they were placed with other family members. Adult Protective Services is handling care and follow-up.

Hinged sentence, because the paperwork is never the whole story but it matters: when the law finally writes down what happened, it stops being “a rumor behind a fence” and becomes a record the fence can’t hide.

The police chief confirms key details in a measured voice that sounds like he’s protecting himself from the emotional weight. He says the victim was removed and transported to the ER at Anson General Hospital for a medical evaluation, treated for minor injuries, and released to a family member. He says she’s physically healthy. Ann, still stuck on the idea of the cold, checks with a meteorologist about the temperature that night: about 57 degrees Fahrenheit at 8:00 p.m. on November 22. It’s not a blizzard. It’s not dramatic weather. But it’s cold enough that you need a jacket, and it’s cold enough that someone not dressed for it, confined and scared, could be at risk.

And that’s the number that keeps pulsing through the rest of the story—57°F—because it turns the scene from “this is bad” into “this could have gone worse fast.” The police chief says Emily wasn’t dressed for the weather, which is one reason she was sent for evaluation. Ann asks if Emily had shoes or socks. The chief believes she did. Ann asks what she was wearing. He recalls a T-shirt and jogging pants. Ann says what everyone is thinking: not enough to keep you warm.

Ann asks if there was water in the kennel. The chief says no. Ann asks how long she was in there. The chief says they believe approximately an hour. Ann asks about chains. The chief clarifies: she wasn’t chained, but there was a wire cable keeping the door closed so she couldn’t get out. Ann repeats it, because repeating it makes it real. “Keeping the door closed so she couldn’t get out?” The chief answers, “Yes, ma’am.”

Candy was initially booked into jail that night, the chief says. She made bond the next morning. Further investigation revealed more serious charges, and working with the district attorney and investigators, they upgraded the case. They obtained another warrant, rearrested her, and booked her back into jail. The chief says it’s a disturbing case, shocking to the conscience, and that protecting vulnerable community members is taken seriously. He says a benefit of being a small department is that the same officers who helped the victim have been able to continue working the case, which keeps them active and focused on helping.

Ann asks if the department had been called out to the house before. The chief says the neighborhood is pretty quiet, mostly barking dog complaints and noise complaints, and emphasizes that if someone was heard screaming for help in a backyard, it would be dealt with immediately.

Ann asks about the former police chief connection. The chief acknowledges Candy was the wife of a former chief, but says that chief had been gone from the department for several years and nobody currently working there worked with him.

Ann asks what he wants to say to the community. Did Justin do the right thing? The chief answers without hesitation: absolutely. They’re proud of him. And then he says the sentence that communities put on banners but don’t always practice: if you hear something, say something. He says Justin’s call activated programs and resources that helped immediately and will help in the future.

Hinged sentence, because the moral is not complicated but it is expensive: when one person refuses to mind their business, it can become the first honest act a victim has ever been given.

The timing makes it worse in a quiet way. It was just a few days before Thanksgiving. Ann asks the chief if he thought about it on Thanksgiving. He says he’s been thinking about it every day since. It’s not a case they can set down, he says, because the department is small and it has their full focus. Ann asks about town, about what kind of place Anson is. The chief says it’s small, tight-knit, good people, and they don’t see a lot of “stuff like this” often. He says crime exists everywhere, but on a smaller scale there. And yet, here it is, in the backyard of a home on Liberty Way.

Justin, when asked what he wants other people to take away, doesn’t talk about politics or punishment or internet fame. He says: be kind. Speak up when needed. Look out for loved ones and neighbors. Listen a little more. Keep your eyes open a little more. Do what you can to help. And he says something that lands with the weight of hard experience: never trust anybody 100%, because you never know who your neighbor is. Some people have dark sides hidden. If you’re sending your kids somewhere, pay attention. Ask questions. Watch for what’s going on around them. Because you could send someone you love into a situation like that and never know.

Ann tells him he may have saved Emily’s life. Justin says, “Yes, ma’am,” in a voice that sounds like he’s still trying to accept that it’s true.

And through all of it, the phone flashlight keeps returning in your mind—the same little beam that first tried to make sense of a scream, then became evidence over a fence, then became, in the aftermath, a symbol of what it means to pay attention in a world full of tall fences. The flashlight didn’t rescue Emily by itself. It didn’t unlock the cable. It didn’t make Candy feel remorse. But it did something that mattered almost as much: it made the truth visible long enough for help to arrive.

Justin says, in the clip, “This won’t happen to you ever again.” He says it like a vow he’s making on behalf of every adult who ever looked away. He says it to Emily, but he’s also saying it to himself. “It’s okay, sweetie,” he repeats. “It is okay.”

Emily answers the only way she knows how, the way you answer when your world has trained you that fear is a constant: “I’m scared.”

Justin doesn’t argue with her fear. He doesn’t tell her she’s being dramatic. He doesn’t demand she calm down to make the situation easier for everyone else. He just stays there—behind a fence, phone in hand, voice steady—until the officer can get her out. “I’m your neighbor,” he tells her. “I got you help. Okay?”

And that’s the payoff that lingers after the legal updates, after the charges, after the bond and the rearrest, after the interviews and the procedural statements and the meteorologist confirming 57°F like weather can testify: a 24-year-old neighbor heard something wrong and chose to become inconvenient. He chose to be the person who makes the call. He chose to keep recording when his hands wanted to shake. He chose to keep talking when silence would have been easier. He chose to shine a light—literal, small, unglamorous—over a tall fence.

The last hinged sentence belongs to anyone who’s ever hesitated before dialing 911 because they didn’t want to be “that neighbor”: sometimes the only thing separating a routine night from a rescue is the moment you decide you’d rather be wrong than be quiet.

News

Teen Cries Out During Sentencing — 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 𝐌𝐨𝐦 & 𝟑 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐬, Then Begs Judge for Mercy | HO

Teen Cries Out During Sentencing — 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 𝐌𝐨𝐦 & 𝟑 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐬, Then Begs Judge for Mercy | HO Andrea’s Tuesday…

Husband Tried To 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥 His Wife, But She Survived & Husband’s 𝐁𝐨𝐝𝐲 Was Soon Found In A Dumpster | HO

Husband Tried To 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥 His Wife, But She Survived & Husband’s 𝐁𝐨𝐝𝐲 Was Soon Found In A Dumpster | HO…

My Sister Took Everything from Me—So I Waited for Her Wedding and Gave a Gift She’ll Never Forget… | HO

My Sister Took Everything from Me—So I Waited for Her Wedding and Gave a Gift She’ll Never Forget… | HO…

Perfect Wife Slipped Her Husband Strong Sleeping Pill & 𝐂𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 Him For His Infidelity | HO

Perfect Wife Slipped Her Husband Strong Sleeping Pill & 𝐂𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 Him For His Infidelity | HO The bell finally rang….

Antifa Bully Harasses Woman, Then Her HUSBAND Shows Up… | HO

Antifa Bully Harasses Woman, Then Her HUSBAND Shows Up… | HO And then it happens fast, the way these things…

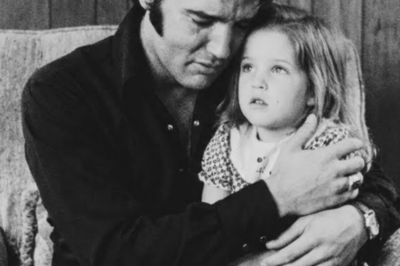

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

End of content

No more pages to load