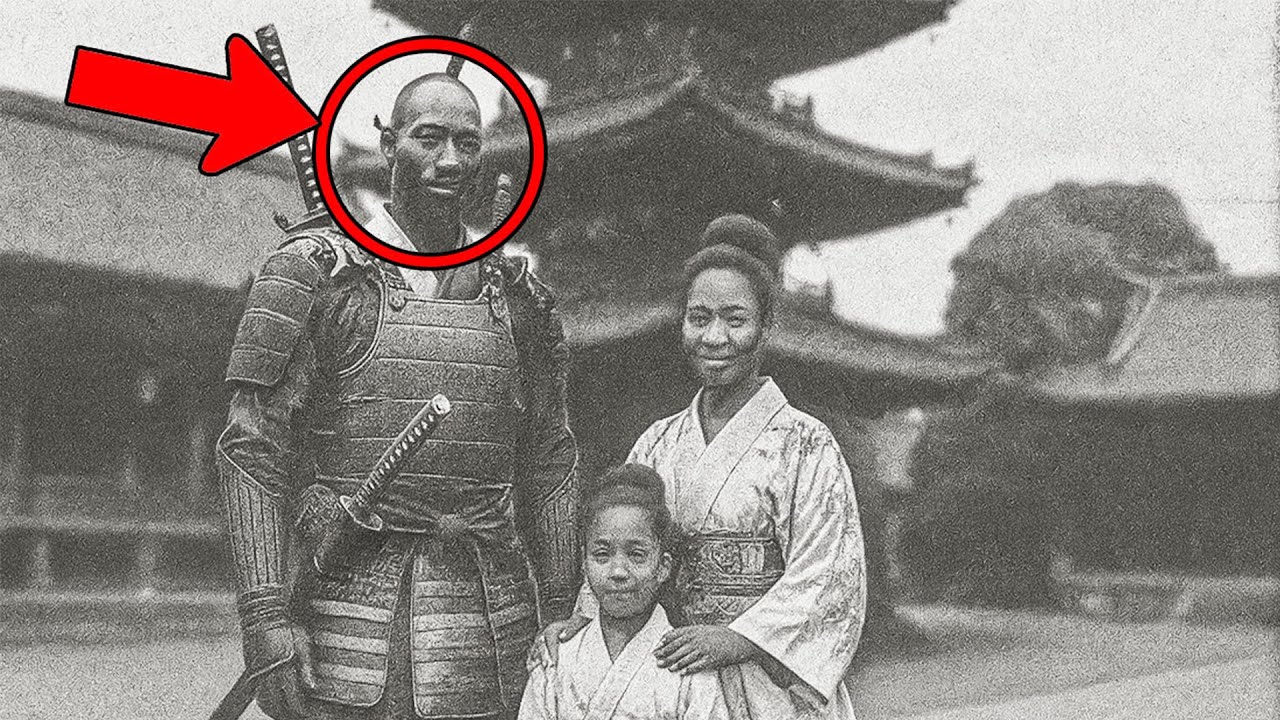

Invincible Black Samurai Poses For Family Photo — Historians Zoom In and Uncover a Chilling Secret | HO!!

It began, as so many historical earthquakes do, with something deceptively small—a thin envelope, unmarked and silent, slipped through the mail slot of the Kyoto Historical Archives on a cool Tuesday morning in March 2019. There was no sender, no return address, no explanation. Only a stiff cardboard sleeve containing a single black-and-white photograph.

Dr. Kimiko Matsumoto, whose calm precision and encyclopedic knowledge of Sengoku-era artifacts were legendary among her colleagues, lifted the photograph toward the morning light. She expected little. She did not yet understand that this one image would upend centuries of scholarship, challenge everything historians believed about one of Japan’s strangest legends, and force her team into a chilling confrontation with a truth that was far more tragic than anyone imagined.

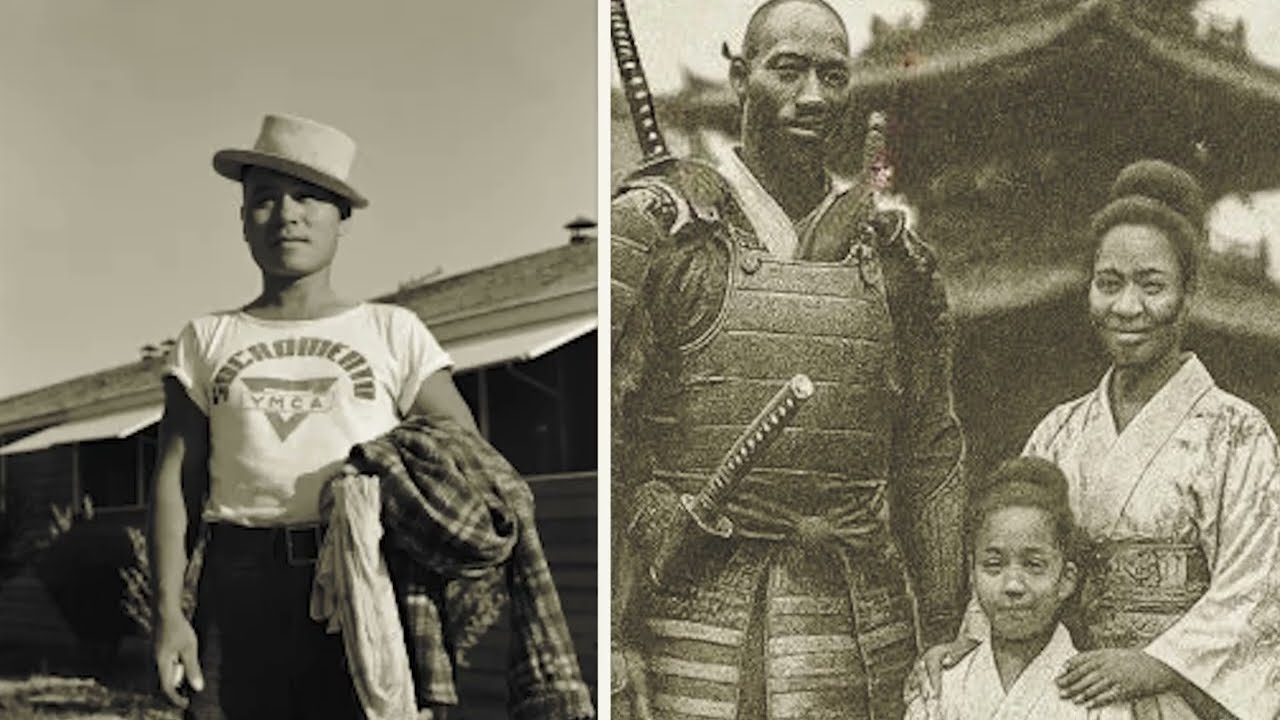

Her breath caught before she fully understood why. The photograph was old—at least a century, perhaps more. Sepia tones feathered around the edges. The focus was soft, but not so soft that the three figures at the center were hard to distinguish. A woman in an ornate kimono. A small child standing in front.

And behind them—a man in full samurai armor. A man towering above both, easily over six feet tall, his posture absolutely still beneath the weight of two swords. His skin was unmistakably dark even through the aging monochrome. His face calm, solemn, familiar in a way that made her heart pound violently.

It can’t be… she whispered.

But it could be. And it was.

There had only ever been one black samurai in recorded Japanese history. One man whose presence was so extraordinary that even the great Oda Nobunaga, conqueror, innovator, and unifier of Japan, had been fascinated by him. One man whose name had passed into legend—Yasuke.

But photography did not exist in Yasuke’s lifetime. It wouldn’t be invented for nearly 250 years. And Azuchi Castle—the unmistakable structure faintly visible in the background—had burned to the ground in 1582.

Dr. Matsumoto’s hands trembled. There could be only two explanations: either the photograph was a forgery of unrivaled skill, or it was a window into something historians had never been willing to consider—something impossible, unthinkable, and deeply dangerous.

She called an emergency meeting.

By dusk, three experts assembled in a locked conference room: Dr. Matthew Whitmore, a photographic historian from Oxford; Professor Hiroshi Tanaka, the most respected Sengoku scholar in Japan; and Dr. Phoebe Green, a forensic imaging specialist with a reputation for seeing what others missed. The photograph was projected onto a white wall, and for several minutes, no one spoke. The silence was heavy, reverent, fearful.

The armor was correct for the late Muramachi period. The crest on the shoulder was the Oda clan’s. The woman’s kimono belonged to a style fashionable only in the 1580s. The child’s sandals—their stitching, their pattern—were from the same era. Every element was precise. Every detail belonged to a world that should not have been captured by a camera.

That night, they worked without pause. They analyzed the grain, spectrum shifts, oxidation patterns. Dr. Whitmore dated the photograph’s paper to sometime between 1860 and 1870. “Impossible,” he whispered again and again, running his fingers through his hair. “This is modern photography. But the subjects are not modern. Nor is the architecture.”

Professor Tanaka was the first to speak a truth none of them wanted to admit.

“Look at their eyes,” he murmured, stepping forward. “Look at the child. Look at the woman. Look at Yasuke.”

Their expressions were not posed. They were not stylized. They held something raw. Something candid. Something painfully alive. Old paintings and scrolls captured ideals. But photographs—true photographs—captured humanity.

“This is not a stylized portrait,” Dr. Green whispered. “This is a moment. A real moment.”

But how? And why would someone send it now?

Seven days passed. The team barely slept. They compared the photograph to every known image and record of Azuchi Castle. They studied maps. They traced wood grain on the castle’s shattered beams. Dr. Green magnified the stones behind the figures to 400%, examining scorch patterns. The stones were charred—evidence consistent with the great fire that destroyed the castle in 1582. And yet the photograph itself could not predate 1839, the invention of photography.

The contradictions were violent.

On the eighth night, something shifted. Dr. Whitmore slammed his hand on the table. “The grain is wrong,” he said. “This isn’t an original photograph. It’s a reproduction. But of what?”

It was the question that finally led them to the Tanaguchi archives and the seven paintings that would reshape their understanding of Yasuke’s fate. The paintings were arranged chronologically, each one a copy of the last, each more faded, more fragile. A 16th-century original. A 17th-century copy. Another from the 1700s. Layers of time, generations of hands preserving a single scene: a tall black samurai, a woman, a child, the ruins of Azuchi behind them.

Then came the seventh painting. A masterpiece of hyper-realism from 1923. So detailed, so breathtakingly precise that even experts mistook it for a photograph.

And suddenly, everything made sense.

The “photograph” that arrived anonymously was not a time-bending artifact. It was a highly accurate print made in the 1960s by the painter’s grandson—an attempt to duplicate his grandfather’s hyper-realistic preservation of a centuries-old family legacy. The shock was not in the technology. The shock was in the truth behind the image itself.

Because these paintings were not works of imagination.

They were a record.

A record of a man historians assumed died in 1582. A man who had, in fact, lived.

For as Professor Tanaka confirmed, the Tanaguchi family line began with a woman whose name had been lost to time… but whose face was unmistakable in the paintings. The child’s lineage continued through the centuries, the family guarding the memory of the foreign warrior who had saved them.

Yasuke had survived the fall of Nobunaga. He had escaped execution. And he had chosen obscurity, exile, and silence to protect those he loved.

The realization struck the historians like a blade.

The invincible samurai had lived. But he had lived as a fugitive.

The team worked in stunned quiet, piecing together fragments of oral history, forgotten temple records, and family story scrolls. Slowly, painfully, the truth emerged: Yasuke had been smuggled out of Kyoto by a small circle of loyalists who believed Nobunaga’s dream should not die with him. He hid in remote mountain settlements. He abandoned his swords. He took a new name. He became a husband. A father. A protector.

He watched from the shadows as the world moved on without him—his deeds erased, his honor unrecognized, his existence denied by history.

Because to be remembered would have meant death for his family.

He lived for them, not for glory.

And when his child grew, he posed for the portrait that began the Tanaguchi family’s centuries-long tradition of preservation. A final, quiet statement. A whisper of truth.

I was here.

I lived.

I loved.

But the real tragedy—and the real secret of the photograph—did not reveal itself until the team compared the first painting to the last. Dr. Green noticed it first.

In the earliest painting, Yasuke stands tall, armored, proud.

In the second, his posture changes—a slight hunch, a tension in the jaw.

By the fourth painting, his expression carries exhaustion. Fear. A man hunted.

By the sixth, his sword is gone.

By the seventh—the hyper-realistic masterpiece—his eyes tell a story no one had dared to imagine. Sorrow. Fatigue. A man who has lived too long in the shadows.

A man who has forgotten sunlight.

A man who knows that simply being seen could destroy the people he loves.

The chilling secret historians uncovered was not a mystery of time travel, sorcery, or unknown technology.

It was the truth that Yasuke—the towering warrior who had fought beside one of Japan’s greatest leaders—had spent the rest of his life running from the world that once celebrated him. Condemned not by an enemy, but by history itself.

The photo was a memorial, not of victory, but of sacrifice.

A reminder that every legend has a human cost.

And so the historians told the world. At a packed press conference, Dr. Matsumoto stood before a screen displaying all seven paintings. Her voice wavered as she spoke.

“For centuries, we believed Yasuke vanished after the fall of Oda Nobunaga. We now know he didn’t. He lived. He became a father. A protector. But he lived in hiding. With fear. With loss. With devotion. His strength was not only in battle—it was in the sacrifice of choosing anonymity over honor, so his family could survive.”

The world reacted with awe, disbelief, reverence.

But for Dr. Matsumoto, the discovery left an ache. Every time she stood before the paintings, she whispered the same quiet thought:

Even giants can be forgotten.

Even heroes can be forced to disappear.

And perhaps that was the most haunting truth of all: The invincible black samurai—whose courage had shaken the foundations of a nation—had spent his final years as a ghost, walking unseen through the world he once helped shape.

Not because he was weak.

But because love demanded it.

The photograph, once thought impossible, was not proof of a miracle. It was proof of something far more human—and far more tragic.

A warrior who could not be defeated in battle had been defeated by history’s silence.

And somewhere, deep in the Tanaguchi bloodline, descendants still carried his face, his memory, his legacy.

Not in glory.

But in quiet endurance.

Just as he did.

News

Woman Born in 1843 Talks About the One Thing She Regrets Most – Enhanced Audio | HO

Woman Born in 1843 Talks About the One Thing She Regrets Most – Enhanced Audio | HO I think about…

Teen K!ller Laughs in Judges Face, Thinking He’s Undefeated — Then His Grandmother Stands Up | HO

Teen K!ller Laughs in Judges Face, Thinking He’s Undefeated — Then His Grandmother Stands Up | HO “Mr. Cole,” Judge…

This Baby Isn’t Ours’—Her In-Laws Beat the Widow Until a Cowboy Rode In | HO

This Baby Isn’t Ours’—Her In-Laws Beat the Widow Until a Cowboy Rode In | HO Sometimes salvation rides in so…

Dad 𝐀𝐛𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 His 𝗗𝗜𝗦𝗔𝗕𝗟𝗘𝗗 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 With Mother’s APPROVAL—She Got 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗻𝗮𝗻𝘁, They Did THIS to Hide It | HO

Dad 𝐀𝐛𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 His 𝗗𝗜𝗦𝗔𝗕𝗟𝗘𝗗 𝗗𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿 With Mother’s APPROVAL—She Got 𝗣𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗻𝗮𝗻𝘁, They Did THIS to Hide It | HO On a…

10 Hours After She Left With Her New BF For Hawaii, He K!lled Her When She Discovered He Had.. | HO

10 Hours After She Left With Her New BF For Hawaii, He K!lled Her When She Discovered He Had.. |…

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!!

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!! Andre Johnson. Inmate #44702….

End of content

No more pages to load