It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!!

The photograph lived in darkness for 124 years, pressed flat inside a climate-controlled drawer at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, cataloged in a way that made it easy to overlook.

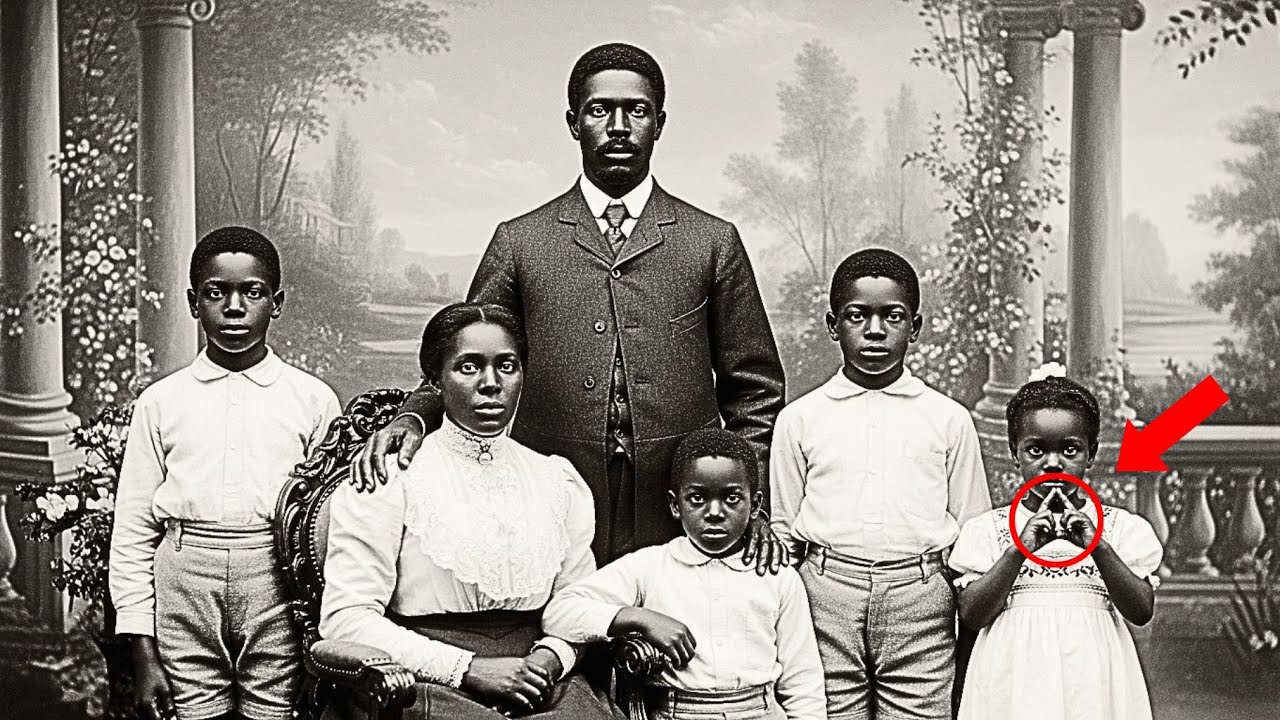

In March 2024, Dr. Maya Freeman slid the drawer open during a routine digitization project, the kind that usually felt like careful housekeeping for history. The sepia portrait inside was remarkably intact, the tones only slightly faded, the paper still firm. Six people in a studio pose from 1900, stiff with the long exposure of early photography: a Black family, formal and composed, as if dignity could be nailed into place.

It was just a family photo—until Maya looked closely at one child’s hand.

Maya had spent her career studying post-Reconstruction African American communities, the years after 1877 when the country’s promises thinned out and the South tightened around Black families like a closing fist. She’d seen thousands of images: studio backdrops painted with fake gardens, artificial columns, ornate chairs meant to lend status to people the world refused to grant it.

This portrait had all of that. The father stood at the back in a dark wool suit that looked new, likely the finest thing he owned. One hand rested on his wife’s shoulder with a steadiness that said, “We are still here.” The mother sat in an ornate chair, high-neck dress, lace at the collar, hair pulled back severe and neat—composure that didn’t quite hide the exhaustion in her eyes.

Four children arranged themselves around their parents. Three boys in identical knickers and white shirts with stiff collars stared at the camera with an intensity that felt too old for them, as if childhood had been edited out. A little girl, maybe four or five, stood slightly apart. Her face was softer than her brothers’, less burdened, as if she still believed the world might be kind.

Maya adjusted her magnifying lens under the examination light. She was looking for the usual things: the studio mark on the card stock, a hint of location in the backdrop, any clue that could put names to faces. She told herself this was simply a task: scan, label, move on.

Then her eyes dropped to the youngest child’s hands.

Everyone else held their hands in the standard poses of the era—folded, clasped behind backs, resting naturally. The little girl’s left hand, however, was placed deliberately against her small chest. Three fingers extended upward. Index and middle crossed tightly over the thumb.

Too precise to be accidental. Too intentional for a child fidgeting through a long exposure.

Maya felt her breath catch like she’d stepped into a cold room. She took a high-resolution photo of the hand detail, zoomed in until the tiny crossed fingers filled her screen. The painted garden behind them suddenly felt less like decoration and more like camouflage, a stage set built to hide whatever truth was being signaled in plain sight.

“What were you saying?” Maya whispered at the photo, absurdly, as if the child could answer.

She checked the acquisition records. Donated in 1987 from an estate in Chicago. Part of a larger collection of early African American portraiture. No names recorded. No provenance beyond “Mississippi family, circa 1900.” Six faces frozen in time and one small hand making a sign that didn’t fit the sanitized story Maya had been taught: slavery ended in 1865, the Underground Railroad ended, the danger eased, the country moved on.

Maya pinned an enlargement to her office corkboard and wrote one line under it in thick marker: WHY WOULD A CHILD NEED A CODE IN A PORTRAIT?

Then she made herself a promise she didn’t fully understand yet—if that hand meant something, she would follow it until it had a name.

For five days, Maya lived inside that photograph. She barely slept. Her office became a paper storm: Mississippi maps from 1900, census rolls, city directories, Reconstruction histories, scholarly texts on survival strategies under Jim Crow. Her laptop stayed open to databases until the screen dimmed itself in protest. The little girl’s hand gesture haunted her like a repeating note.

She started methodically. She searched academic journals for documented hand signals used by enslaved people and their descendants. She found references to coded songs, double-meaning sermons, whispered routes, rumored quilt patterns. She found plenty of arguments about what was real and what was legend. She found nothing that matched three crossed fingers held to the chest.

On the sixth morning, her frustration sharpened into decision. She contacted Dr. Elliot Richardson, an elderly historian at Howard University who’d spent forty-five years studying covert resistance networks from slavery through Jim Crow. Maya attached her best high-resolution images, including the tight zoom on the child’s hand. She wrote one sentence: Have you ever seen this?

Two hours later, his response arrived, marked urgent.

This changes everything I thought I knew. Call me immediately.

Maya’s hands shook slightly as she dialed. When Elliot answered, his voice wasn’t calm; it was electric.

“Where did you find this photograph?” he demanded.

“Smithsonian archives,” Maya said. “Donated in ’87. Mississippi, 1900. No identification. Why? What am I looking at?”

Elliot exhaled hard, as if steadying himself. “Maya, I need you to understand something. The Underground Railroad didn’t end in 1865. That’s the version we teach because it’s neat. Slavery ended. Railroad shut down. Everybody lived happily ever after.”

Maya grabbed her notebook, pen poised. “Explain.”

“After Reconstruction collapsed in 1877,” Elliot said, voice low, “the South became a minefield for Black people. Night riders. Legal traps. Economic squeeze. Violence that was both random and targeted. Families needed protection networks just as desperately as they did during slavery—maybe more—because now they were supposed to be free and had no federal shield.”

Maya stared at the photo pinned to her wall. “So the networks continued.”

“They evolved,” Elliot corrected. “Conductors, station masters, the ones who survived, adapted. New codes. New safe houses. New routes to northern cities. Warning systems. They ran in absolute secrecy from roughly 1877 through the 1920s.”

Maya’s pen hovered. “And the hand signal?”

Elliot paused, and when he spoke again his voice trembled. “I’ve read oral histories. Interviewed descendants. Heard rumors of hand signals for decades—whispers, fragments. But I’ve never seen photographic proof.”

Maya swallowed. “So what is it?”

“What you’re looking at,” Elliot said, “is called the reload signal. It meant a family was connected, prepared, ready to help or receive help.”

Maya stared at the little girl’s composed face, her small hand held with tension. “Reload,” she repeated, almost afraid of the word.

“It was deliberately taught to children,” Elliot said.

“Why children?” Maya asked, and she already hated the answer she suspected.

“Because children could move through communities without raising suspicion,” Elliot said. “And if parents were arrested or worse, the children needed a way to identify safe families. That gesture told the right eyes: we’re part of it. We know. We can be trusted.”

Maya felt cold move down her spine as she looked at the little girl in her white dress, holding a signal that meant her parents had prepared her for the possibility of not being there tomorrow.

The photograph wasn’t just a portrait anymore. It was a survival document.

And Maya understood her promise had teeth now.

If the child’s hand was a code, Maya needed a starting point that wasn’t theoretical. She flipped the paper print carefully and examined the back under magnification. A faint stamp, partially degraded but still legible: Sterling & Sons Photography, Natchez, Miss.

Natchez sat on the Mississippi River, once a hub of cotton wealth and slave auctions, then a Jim Crow stronghold where Black families lived in that precarious space between liberation and terror. Maya spent two days buried in Natchez records. She found city directories listing Sterling & Sons from 1892 to 1911, one of the few studios in the region known to serve Black clientele. She tracked newspapers and discovered an obituary from 1928 for Marcus Sterling, described as a respected colored businessman who served his community with dignity for thirty years. The obituary mentioned his son, James Sterling, who left Mississippi in 1911 and continued a smaller portrait business in Chicago.

Chicago. Donated in 1987 from an estate in Chicago.

Maya followed the thread to a name in modern records: Vanessa Sterling Hughes, James Sterling’s great-granddaughter, retired art teacher living on the South Side. Maya drafted an email that tried to balance professionalism with urgency. She included a scan of the backstamp and wrote, simply: I believe your great-grandfather’s studio may have documented something historically significant. Would you be willing to speak?

Vanessa responded within hours.

My great-grandfather rarely spoke about Mississippi, but he kept things. Come see me.

Three days later, Maya sat in Vanessa’s living room surrounded by five generations of family photos. Vanessa, in her seventies, silver locs and warm eyes that didn’t miss much, moved with careful purpose. She brought out a wooden trunk, scarred and heavy.

“He carried this trunk from Mississippi to Chicago in 1911,” Vanessa said. “He wouldn’t let anyone look inside while he was alive. After he died, my grandmother inherited it, but she didn’t know what to do with what was in there.”

Vanessa lifted the lid. Inside were hundreds of glass plate negatives, wrapped and preserved. Portraits of Black families from Natchez between 1892 and 1911. Beneath the negatives: three leatherbound journals in James Sterling’s handwriting.

“My great-grandfather wrote everything down,” Vanessa said, flipping open the first journal. “Every family who came to the studio. Dates, names… sometimes notes about why they needed portraits made.”

Maya leaned in, heart pounding. “Can you find September 1900?”

Vanessa turned pages with reverence until her finger stopped. “September 14,” she read. “Coleman family. Six portraits. Express order. Three-day rush. Special arrangement.”

“Coleman,” Maya whispered, tasting the name like it might unlock a door. “What does ‘special arrangement’ mean?”

Vanessa looked up, and something inherited—knowledge, maybe, or instinct—settled into her expression. “My great-grandfather’s studio wasn’t just a business,” she said. “It was a safe place. A checkpoint. Families who needed help knew they could come to him.”

Maya’s throat tightened. “Was he part of the network?”

Vanessa didn’t say the word network like it was casual. She said it like it still needed to be handled carefully. “He never called it by name, not even in his journals,” she said. “But yes. He documented people who were about to disappear—by choice, to survive.”

Maya stared at the entry again. Coleman family. Six portraits. Three-day rush. Special arrangement. A family documenting themselves before they became ghosts.

“Do you have the glass plate negative for this portrait?” Maya asked.

Vanessa’s mouth curved into a small, knowing smile. “I think I can find it.”

She lifted a wooden box from the trunk. Inside, glass plates organized chronologically in yellowed cloth. Vanessa moved through them until she reached September 1900. She held one plate up to the light.

There they were—father’s protective stance, mother’s formal posture, three boys, and the little girl with her hand held to her chest in that deliberate gesture.

Maya whispered, “That’s her.”

Vanessa nodded. “That’s them.”

And now the code had a name, a date, and a studio that served as a doorway.

They took the glass plate to the Art Institute of Chicago. In a conservation lab that smelled faintly of gloves and clean paper, a specialist named Robert positioned the plate beneath a high-resolution scanner built for historic negatives. The resulting digital image was astonishing: every texture of fabric, every strand of hair, every line on a face rendered with clarity that made the people feel suddenly present.

Robert zoomed in on the little girl’s hand. “That’s intentional,” he said. “See the tension in the fingers? She held that through the exposure. That’s hard for a child.”

“She was trained,” Maya said quietly, and the word landed heavy.

Robert dragged the cursor to another detail. “Look at the mother’s left hand, resting in her lap. That ring—zoom in.”

Maya leaned closer. The ring bore a tiny engraving: three interlocking circles forming a triangle.

Vanessa frowned. “What does that mean?”

Maya photographed the detail. “I don’t know yet,” she admitted. “But it’s connected.”

Back at Vanessa’s home, Maya returned to the journals with new eyes. She noticed marks beside certain names—stars, circles, triangles—notations that weren’t decoration. When she flipped back to the Coleman entry, her breath stopped.

In the margin beside “Coleman family,” James Sterling had drawn the same symbol: three interlocking circles.

“He was marking network families,” Maya said, the sentence half wonder, half grief.

Vanessa traced the ink with a fingertip. “So it wasn’t just in his head,” she murmured. “He recorded it.”

Maya flipped through more pages. An entry from August 1900 caught her eye: Reverend Patterson visited, discussed arrangements for autumn departures. Twelve families confirmed.

“Twelve families,” Maya said, looking up. “Preparing to leave.”

Vanessa’s voice softened. “Why? What happened in Natchez in 1900 that made twelve families run?”

Maya opened her laptop and searched local newspapers. Within minutes, the screen filled with articles from the Natchez Democrat, August through October 1900. Reports of a disputed land claim followed by waves of intimidation. Black landowners targeted. Churches threatened. Homes burned. The language was careful in print, but the meaning was not.

“The portrait was taken at the height of it,” Maya said, pointing to the date. “September 14. They were documenting themselves before they disappeared.”

Vanessa’s eyes glistened. “So my great-grandfather helped them do it.”

Maya nodded. “He gave them proof they existed—before they had to erase themselves to stay alive.”

In that moment, the ring’s symbol, the child’s hand signal, the three-day rush order—everything tightened into a single truth: this was not a family photo; this was a passport made of paper and silence.

And the key number—124 years—suddenly felt less like time and more like a dare history had been waiting for someone to accept.

Maya immersed herself in Natchez records from late 1900. The violence wasn’t random; it targeted Black families who had acquired land, built businesses, gained any measure of independence since emancipation. Property records revealed the Coleman family owned forty acres outside Natchez, purchased in 1892. The father’s name surfaced: Isaac Coleman, born enslaved in 1861, freed as an infant, and somehow—against a world designed to prevent it—he bought land.

In an 1899 agricultural report, Isaac’s name appeared among the few Black farmers successfully growing cotton and vegetables for market. Success that, in that time and place, could paint a target on a man’s back.

Then Maya found a notice in the Natchez Democrat from October 1900: Coleman property, forty acres, forfeited for unpaid taxes. A legal theft disguised as paperwork.

By then, the Colemans were gone.

Maya called Dr. Richardson again and shared everything. Elliot listened, then gave her a direction that sounded like a test. “If they left in late 1900,” he said, “they headed north. Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland—cities with growing Black communities where a family could disappear into a larger population.”

Maya searched 1910 census records. Isaac Coleman was too common a name; it multiplied across pages. She needed another anchor. She returned to the photo and estimated the children’s ages: the oldest boy perhaps twelve, the middle ten, the youngest around seven, the girl about four or five. She looked for Black families in northern cities with four children matching those age ranges.

It was tedious work—days of cross-referencing directories, church records, school enrollments. But on a night when her eyes felt grainy and her coffee had gone cold, she found them.

Detroit, Michigan. 1910 census: Isaac Coleman, age forty-nine, laborer. Wife Esther, forty-four. Children: Thomas, twenty-two. Benjamin, twenty. Samuel, seventeen. Ruth, fourteen.

Maya sat back in her chair and let out a breath she didn’t realize she’d been holding.

“They made it,” she whispered.

Then she noticed something else on the record: in the margin, the census taker’s handwriting—family declined to provide prior address.

Even ten years later and hundreds of miles away, they were still protecting themselves. Natchez remained buried like a name that could summon danger.

Maya stared at “Ruth,” the little girl in the white dress with the crossed fingers. She’d grown up. She’d survived. She’d become someone with a new life and an old code.

Maya needed to know what happened to Ruth Coleman.

Tracking Ruth through the next century was like chasing a shadow across paper. Maya found Ruth in 1918 Detroit school records, graduating from Cass Technical High School—one of the few Black students in her class. Then, a marriage certificate from 1921: Ruth Coleman married William Harris, a postal worker. After that, the trail blurred into domestic invisibility—no occupation listed, addresses that shifted within the same neighborhoods, the quiet work women did that rarely made official record.

Then Maya found Ruth again in the archives of Second Baptist Church of Detroit, an institution with its own deep history of refuge. Ruth served as a Sunday school teacher from 1925 to 1964.

Maya called the church and spoke with an elderly deacon and historian named Frank Morrison. When Maya explained her research, Frank didn’t hesitate.

“Mrs. Harris,” he said immediately. “Oh, I remember Sister Ruth. She taught my Sunday school class in the 1950s. Quiet woman. Very dignified. Warm with children.”

Maya’s pulse jumped. “Did she ever talk about Mississippi?”

“Never,” Frank said. “A lot of folks who came up from the South didn’t speak on it. Too much pain. Too many reasons to keep it shut.”

“Did she have children?” Maya asked.

“Three daughters and a son,” Frank said. “The youngest daughter, Grace, still here in Detroit. She’s a nurse at Henry Ford.”

That night, Maya called Grace Harris Thompson. Grace was cautious at first—another historian, another request, another stranger asking to open old doors. But when Maya described the photograph and the child’s hand, Grace’s voice cracked.

“I need to see that picture,” Grace said. “Send it right now.”

Maya emailed the scan. Ten minutes passed, then her phone rang again. Grace was crying.

“That’s my mother,” Grace said. “That little girl is my mother. I’ve never seen a picture of her as a child. She always said there weren’t any photos from before Detroit. She said they were lost.”

“They weren’t lost,” Maya said gently. “They were protected.”

Grace inhaled sharply. “The hand signal,” she whispered. “My mother did that once. I was maybe eight. We were at church. An older woman came up—someone visiting from down South. They looked at each other and my mother made that exact gesture. The woman started crying, and they hugged like family, but I’d never seen her before.”

Grace paused, voice thin with memory. “When I asked about it, my mother said, ‘That’s how we used to say hello in the old days, baby.’ That’s all she said.”

Maya closed her eyes for a second, feeling the weight of it. The code hadn’t just survived in archives. It survived in bodies, in gestures passed from life to life.

And now Maya was holding the thread in her hands.

Maya traveled to Detroit to meet Grace. They sat in Grace’s living room, surrounded by photographs of Ruth’s life: a wedding picture from 1921, Sunday school group shots, family gatherings through decades. But there was nothing from Mississippi, nothing from before 1910.

“My mother was a woman of silences,” Grace said, hands folded tight. “She loved us fiercely, but there were rooms inside her we were never allowed to enter. Whenever we asked about her childhood, she’d say, ‘That was another life, baby. This is the life that matters now.’”

Grace stood and brought out a small wooden box. “After she passed in 1987, I found this hidden in the back of her closet,” Grace said. “I never knew what to do with it.”

Inside: a small leatherbound Bible dated 1892, pages worn and annotated in careful handwriting. A cotton handkerchief embroidered with the initials E.C.—Esther Coleman. Three wooden buttons, hand-carved. And a folded piece of paper yellowed with age.

Maya unfolded the paper slowly.

A hand-drawn map. Crude but detailed. Roads. Rivers. Landmarks. Pencil notations: 12 mi to Jackson. Safe house, barn with red door. Avoid main road after dark.

Maya’s voice dropped. “This is an escape route.”

Grace stared at the map as if it might start moving. “She kept this her whole life,” Grace whispered. “And never told us.”

Maya photographed every inch, then noticed a small folded cloth tucked beneath the map. When she opened it, she felt her throat tighten.

A child’s white dress, yellowed with time, embroidered flowers along the hem.

“The dress,” Grace breathed, fingertips hovering like she was afraid to break it. “From the photo.”

“Your mother kept the evidence,” Maya said softly.

For the next hour, Grace offered fragments—never full stories, but pieces that now assembled into a clearer picture. Ruth had two older brothers and one younger brother. Thomas became a factory foreman. Benjamin worked for the railroad. Samuel died young in 1925. Isaac worked in an auto factory until his death in 1933. Esther took in laundry and lived until 1941.

“They never went back to Mississippi,” Grace said. “Not once. My grandfather used to say, ‘That ground is soaked with too much sorrow. I’ll never set foot there again.’”

Maya asked the question that had been sitting in her chest like a stone. “Did your mother ever explain what the hand signal meant?”

Grace thought carefully. “Near the end,” she said. “I asked her straight. I thought maybe she’d finally tell me. She looked at me with these… sad, ancient eyes and said it meant we took care of each other when nobody else would. It meant family wasn’t just blood. It was anybody willing to risk everything to keep you alive.”

Maya sat with that sentence until it stopped sounding like poetry and started sounding like logistics.

Because that’s what it was: love turned into strategy.

With Grace’s permission, Maya interviewed other descendants. She spoke to Thomas Coleman’s grandson, Marcus, seventy-five, who shared stories passed down like sacred contraband.

“Grandpa Thomas was twelve when they left Natchez,” Marcus said. “He said they traveled at night, moving from safe house to safe house. Sometimes a barn. Sometimes a church back room. Sometimes a Black family they’d never met before. But everyone knew the signals. Different hand signs meant different things—danger ahead, safe to stay, keep moving, children present. They practiced them like letters and numbers. Survival education.”

Maya learned the network wasn’t folklore; it was infrastructure. Messages moved through coded letters, trusted messengers, even songs sung at church gatherings with meanings hidden in plain sound. Second Baptist Church wasn’t just a place Ruth taught children Bible stories. It had quietly remained what it once was: a hub of protection, employment assistance, legal help, all carried out in ways that didn’t leave neat official records.

Maya called Dr. Richardson again with her findings. Elliot’s voice was both triumphant and grim. “This rewrites our understanding,” he told her. “We’re taught Black people were simply victims, passively enduring. But they were agents of their own survival. They built sophisticated systems that ran parallel to the nation that refused to protect them.”

Maya looked again at Ruth’s hand in the photograph—the crossed fingers held steady through a long exposure—and understood the child wasn’t just signaling. She was testifying.

And the most astonishing part was that history had been telling on itself the whole time, if anyone had bothered to look.

In September 2024, Maya organized a gathering in Detroit with Second Baptist Church and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. Forty-three people came—children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren of families who fled Mississippi around 1900, scattered over Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, Pennsylvania. Many had never met. Their connections had been quiet, dormant, buried under a century of distance and silence.

Grace stood beside Maya, shoulders squared, holding the worn map in a protective sleeve. Marcus sat in the front row. A woman named Patricia represented Benjamin Coleman’s line. Samuel’s early death left no direct descendants, but his name was spoken like a candle lit.

Maya projected the photograph on a screen. Isaac and Esther. Three solemn boys. Little Ruth in her white dress, hand held to her chest in the reload signal.

“The signal,” Maya told the room, “was a language. Your ancestors created communication systems that kept communities alive when official systems failed them. This wasn’t just resistance. This was brilliance. This was love engineered into survival.”

An elderly man raised his hand. “My great-grandmother ran a safe house in Alabama,” he said. “She never told her children about it. Not one word. Why stay silent so long?”

Grace answered before Maya could. Her voice trembled, then steadied. “Because trauma doesn’t end when the danger ends,” she said. “Because they wanted us to have lives without fear. Because speaking about survival sometimes means reliving what you survived.”

She paused, looking at the faces around her. “But silence has a cost too. It means the courage gets erased. The genius gets forgotten. And the children never learn what it took for them to exist.”

After the gathering, a museum curator approached Maya. “We want a permanent exhibition,” she said. “Not just about the Underground Railroad before the Civil War, but about these post-Reconstruction networks. We want your research to anchor it.”

Maya glanced at the projected image one last time, at Ruth’s hand—small, deliberate, unwavering. She thought of that small U.S.-flag magnet on the Smithsonian drawer, the way it trembled every time the air shifted, as if even the building knew the photo mattered.

“Yes,” Maya said. “It’s time these stories were told.”

In February 2025, the Charles H. Wright Museum opened a permanent exhibition: Hidden Signals: Networks of Survival After Emancipation. The Coleman family photograph anchored the central gallery. Ruth’s hand signal was enlarged and explained—no longer a mystery, no longer an accident, but a testament.

Grace donated the wooden box to the museum collection: the Bible, the handkerchief, the buttons, the escape map, and the dress—still yellowed, still embroidered, still impossible to look at without feeling the weight of what it carried. James Sterling’s journals and glass plates joined them, proof that a photography studio had been more than a business; it had been a checkpoint in a secret geography of survival.

Maya returned to the Smithsonian where it began and requested the record be updated. No longer “unknown family, Mississippi circa 1900.” Now it read: Isaac and Esther Coleman family, Natchez, Mississippi, September 14, 1900. Photograph taken by James Sterling. Child making reload signal is Ruth Coleman (later Ruth Harris), 1896–1987.

As the curator typed, Maya noticed that small U.S.-flag magnet again—still on the drawer lip, still doing its quiet job of holding attention where attention could slip. It wasn’t the same magnet, of course, but it might as well have been. A small symbol, easily ignored, quietly insisting: remember.

Back in Maya’s office, a copy of the photograph stayed pinned to her corkboard. She looked at it every morning. Isaac’s guarded dignity. Esther’s composed strength. Three boys carrying too much seriousness. And Ruth—small and bright, fingers crossed in a code she held steady for a few seconds in 1900 and for ninety-one years in silence afterward.

Outside, Detroit moved through another ordinary day—kids walking to school, nurses going to shifts, people living lives made possible by migrations and choices made in the dark. The photo remained eternal, but now its meaning had a name.

When you look closely at one of the children’s hands, you aren’t seeing a random gesture.

You’re seeing three crossed fingers, a language of survival.

You’re seeing proof that love, when organized, can keep generations alive.

And you’re seeing a little girl’s hand—held to her chest like a promise—finally allowed to speak out loud.

News

A Nurse Marries A Felon While In Prison, He Came Into Her Home With Her Kids & Did the Unthinkable | HO!!!!

A Nurse Marries A Felon While In Prison, He Came Into Her Home With Her Kids & Did the Unthinkable…

Steve Harvey FIRED cameraman on live TV — what desperate dad did next left 300 people SPEECHLESS | HO!!!!

Steve Harvey FIRED cameraman on live TV — what desperate dad did next left 300 people SPEECHLESS | HO!!!! Then…

Homeless boy CRASHED Steve Harvey’s show to say thank you — what Steve did next shocked everyone | HO!!!!

Homeless boy CRASHED Steve Harvey’s show to say thank you — what Steve did next shocked everyone | HO!!!! Steve…

15-year-old CHURCH GIRL said 4 words on Family Feud — Steve Harvey COLLAPSED to his KNEES | HO!!!!

15-year-old CHURCH GIRL said 4 words on Family Feud — Steve Harvey COLLAPSED to his KNEES | HO!!!! Lily Anderson…

They Had Been Together for 40 years, But He Had No Idea Who is Wife Really Was, Until FBI Came! | HO

They Had Been Together for 40 years, But He Had No Idea Who is Wife Really Was, Until FBI Came!…

Detroit Ex-Convict Learned She Had 𝐇𝐈𝐕 & 𝐁𝐮𝐭𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 Her Ex With His New Family… | HO

Detroit Ex-Convict Learned She Had 𝐇𝐈𝐕 & 𝐁𝐮𝐭𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 Her Ex With His New Family… | HO On March 27, 2025,…

End of content

No more pages to load