It was just a family portrait — but the woman’s glove hid a horrible secret | HO

I. The Package

It began with a package.

No return address. No sender’s name. Just a single note scrawled in careful cursive:

“This belonged to my family. I believe it deserves to be seen and understood by more people. Please tell her story.”

Dr. Amelia Richardson, senior curator of post–Civil War African-American history at the American Legacy Museum in Richmond, wasn’t easily startled. She’d handled Confederate diaries, slave auction ledgers, even blood-stained shackles. But something about the plain brown parcel made her pause.

Inside, wrapped in yellowed tissue paper, was a Victorian-era photograph in a carved wooden frame. It was heavy, ornate, the kind of frame that once hung in parlors where families wanted the world to know they had made it.

The embossed mark in the corner read:

“J. Morrison, Portrait Artist — Richmond, VA.”

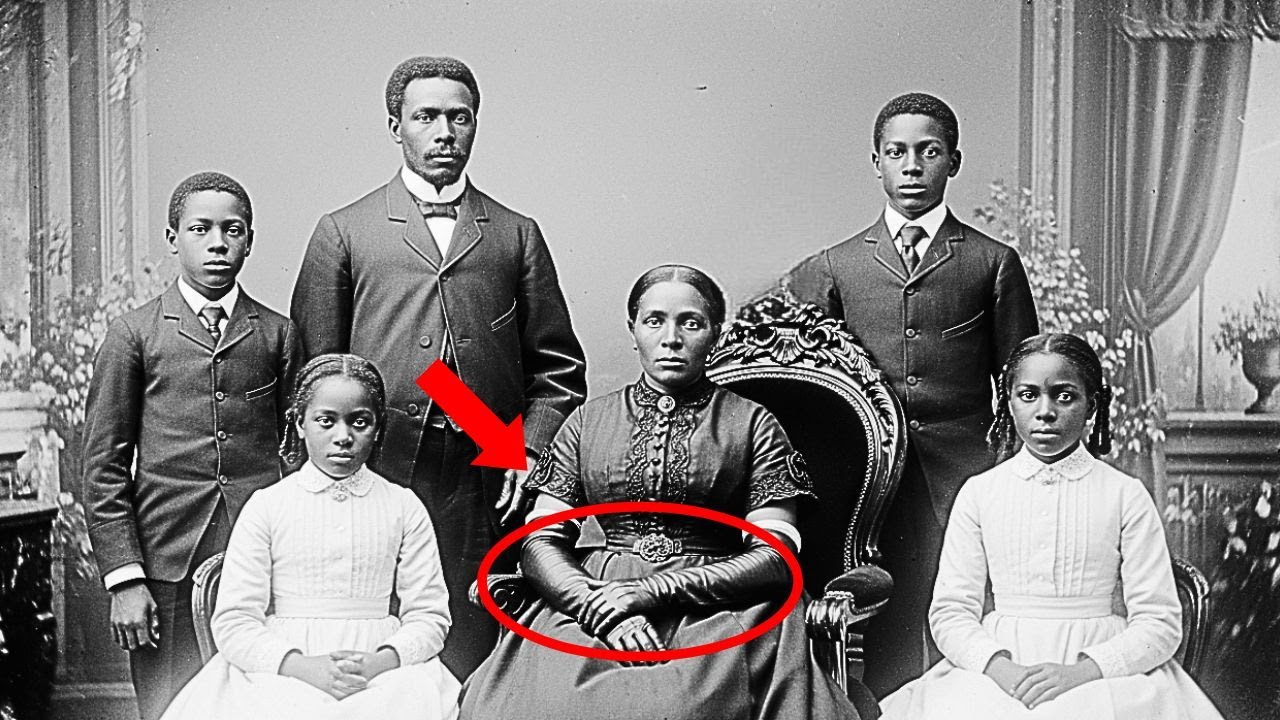

A family of six stared out from 1875.

A man, a woman, four children. Dressed with dignity. Posed with pride. The kind of image born of newfound freedom — a Black family asserting its right to exist in beauty and prosperity just ten years after emancipation.

But even as she studied it, Amelia felt something off. A tension beneath the surface of the image, like a whisper caught in the varnish of time.

And then she saw them.

The gloves.

The woman’s gloves were long — far too long for fashion. They reached nearly to her shoulders, sleek and dark against her elegant dress. In 1875, even the most formal gloves rarely passed mid-forearm. But these… these were different. Deliberate.

It was just a family portrait — but the woman’s glove hid a horrible secret.

II. The Curator’s Instinct

Amelia had seen hundreds of portraits like this one.

In the decade after the Civil War, freed families who had achieved a measure of success often commissioned photographs to declare their humanity to a country still unsure whether it believed in it.

These portraits were acts of defiance.

But there was something haunting about this image. The woman’s expression — calm, composed, yet shadowed by something deeper — seemed to challenge the viewer. Her eyes didn’t simply meet the camera; they looked through it.

Amelia turned the frame over. On the back, in faded ink, someone had written:

“The Family — Richmond, Virginia — June 1875. May we never forget.”

She photographed the inscription and sat back, staring at the photograph. That phrase — may we never forget — felt less like sentiment and more like warning.

That night, she couldn’t stop thinking about the gloves.

Why hide the arms so completely? Why the phrase on the back?

By morning, she knew what she had to do. She called Dr. Marcus Chen, a forensic imaging specialist at Virginia Commonwealth University, a man whose software had helped identify hidden inscriptions in faded daguerreotypes and even reconstruct erased Civil War letters.

“I think there’s something beneath the surface,” Amelia told him. “And not just of the photo.”

III. The Scan

Three days later, the two of them sat in Amelia’s office, surrounded by the quiet hum of climate-controlled air and the soft glow of scanning lights.

Marcus adjusted his equipment. “Beautiful composition,” he murmured. “Morrison was good. Scottish immigrant, progressive for his time. Took portraits of both Black and white families — unusual back then.”

He began the first high-resolution scan, capturing the image in micro-segments. Each pass of the scanner felt like a breath being drawn, as if the photograph itself were preparing to speak.

When the scan finished, Marcus loaded the composite into his laptop and began applying filters — contrast, infrared, shadow enhancement.

At first, everything looked ordinary.

Then the gloves filled the screen.

He zoomed in. Lines appeared where none should exist. Slight bulges, faint textures beneath the smooth fabric.

“Do you see this?” he asked. “Here, near the wrist — and again near the upper arm.”

Amelia leaned closer. The pattern was unmistakable: raised scars, ridges crossing the arms like ghostly fingerprints of violence.

Marcus adjusted the filters. The pattern spread — circular marks near the wrists, deep furrows up to the shoulders. His voice softened. “These aren’t fashion wrinkles. These are… restraints.”

He clicked another filter. The image shifted again.

Chains. Lash marks. Burns.

“God,” Amelia whispered. “They’re scars. Shackles. Lash scars.”

Marcus nodded grimly. “Consistent with restraint injuries. Likely from iron cuffs and repeated whippings. Severe trauma — healed, but permanent.”

The gloves weren’t a fashion statement.

They were armor.

IV. The Hidden History

Amelia sat in silence, staring at the magnified image. The elegant woman in the portrait — once simply a figure of dignity — now seemed transformed into something transcendent.

Who was she?

What had she endured before that photograph was taken?

And why had she chosen to hide it?

She began to search for answers the only way she knew how — through archives, census records, church registries, property deeds. She found “J. Morrison, Photographer” listed on Broad Street, active from 1867 to 1881. But his appointment logs were gone, lost to a fire that had gutted much of Richmond’s business district in the 1890s.

So she turned to the clues in the photo itself.

The father’s hands were rough, callused — a tradesman’s hands. A carpenter, perhaps. The family’s clothing, while fine, was practical. Solid prosperity, not ostentation.

By cross-referencing Freedmen’s Bureau records and property deeds from 1871 to 1875, she finally found a name that made her pulse quicken:

Daniel Freeman — Carpenter, Jackson Ward. Wife: Clara. Children: Elijah, Ruth, Samuel, Margaret.

Four children. The same ages, the same number as in the photograph.

And there, in a Bureau marriage record from 1865, she found a note:

“Bride: Clara (formerly enslaved). Last held by R. Hartwell, Lancaster County. Distinguishing marks: severe scarring on both arms from restraints and punishment.”

Amelia’s hands trembled as she read it aloud. “This is her. This is the woman in the photograph.”

The name had been waiting in the archives for 150 years.

Clara Freeman.

V. The Scars of Lancaster

Clara Hayes Freeman had been born around 1831 on the Hartwell Plantation in Lancaster County, Virginia. The records described her as “field hand, female, age uncertain.” The Hartwells had been wealthy tobacco planters, their ledgers filled with purchases of “equipment,” “seed,” and “negroes.”

One entry, from 1845, mentioned “discipline administered to young female, C.H., following flight attempt.” No details. Just initials. But Amelia didn’t need more.

According to later testimony recorded by the Freedmen’s Bureau, Clara had tried to run away at fourteen — attempting to reach her mother, who’d been sold to North Carolina. She was caught and shackled for six months. The iron cuffs left scars that would never fade.

By her twenties, she’d been whipped repeatedly — for learning to read, for working too slowly, for “insubordination.”

The scars on her arms were the diary her masters didn’t burn.

When the Civil War came, Clara was thirty-three. Amid the chaos of the Confederate collapse, she escaped. She walked for three weeks — hiding by day, moving by night — until she reached Union-occupied Richmond.

Freedom had come at last. But freedom, she discovered, was only the beginning.

VI. The Carpenter and the Survivor

In Richmond, Clara met Daniel Freeman, a free Black carpenter whose parents had purchased their own freedom decades earlier. He was gentle, patient, and practical — the kind of man who built things meant to last.

They married in 1865, just months after emancipation, in a church still half burned from the siege.

Daniel’s letter to his sister, preserved by their descendants, would later describe that moment:

“She carries scars upon her arms that would break most men’s hearts. But she carries herself with a dignity that shames the world that made them. She says she wears long sleeves so our children will see her as whole, not broken.”

In the decade that followed, Daniel and Clara built a life out of ruin. They bought land, raised four children, and founded a small carpentry business on Clay Street.

By 1875, they could finally afford something unimaginable to many freed families — a formal portrait.

Clara insisted on it. She chose her finest dress and commissioned long gloves from a seamstress. She wanted everything perfect.

That photograph would not show a woman branded by cruelty. It would show a family reborn.

VII. The Woman in the Gloves

Through a descendant named Dorothy Freeman Williams, a retired teacher living in Washington, D.C., Amelia learned the rest of the story.

Dorothy arrived at the museum carrying a worn leather portfolio. Inside were letters, deeds, and a yellowed notebook — Clara’s own writings, dated 1889.

“My name is Clara Freeman,” the first page began in careful script.

“I was born Clara Hayes in Lancaster County, Virginia. I was 33 when I first knew freedom. The scars on my arms are my record. They are what I endured, but not who I am.”

Amelia read every line with reverence. Clara described being shackled for six months, whipped for speaking out, beaten for teaching herself letters. She described running through the night toward the fires of Richmond and finding not soldiers, but freedom.

Her words were steady, unbroken by self-pity:

“They made marks on my skin, but they could not mark my soul. My arms remember, but my spirit does not bend.”

Dorothy smiled through tears as Amelia looked up.

“My grandmother Ruth — the little girl on the right — said that photo was her mama’s victory. Clara wanted to show the world what freedom looked like when you refused to be broken.”

VIII. The Photograph’s Meaning

The inscription on the back — May we never forget — had always puzzled Amelia. Now it was clear.

It wasn’t about forgetting slavery.

It was about remembering survival.

The gloves weren’t shame. They were choice — the ultimate act of self-definition. In a world that had stripped her of control, Clara reclaimed it. She decided what would be seen and what would remain her own.

She wore those gloves so her children would see not the scars of a slave, but the hands of a matriarch.

In one letter Daniel wrote to a friend:

“She tells me that showing the scars gives the world power to name her again. Covering them lets her decide who she will be. That, she says, is true freedom.”

Amelia realized that the photograph wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was a declaration.

A woman who had been denied ownership of her own body was now author of her own image.

IX. The Legacy Unearthed

As Amelia and Dorothy continued to dig, they pieced together the rest of the Freeman family’s remarkable story.

Clara and Daniel’s children thrived. Their daughter Ruth became a teacher and kept a diary filled with her mother’s sayings:

“Mama says our scars — the ones we show and the ones we hide — are proof of our strength. She says freedom means choosing how to be seen.”

Clara herself became a leader in Richmond’s Black community, helping found a mutual aid society for formerly enslaved women. Meeting notes from 1878 record her words:

“The scars we carry, whether upon our skin or in our hearts, are not signs of shame but survival. We may choose to show them or not — but never let them define us.”

By 1885, Clara was managing her husband’s business accounts and even owned rental property — an extraordinary achievement for a woman born in chains.

In 1888, The Richmond Gazette published a short piece about “Mrs. C. Freeman, respected colored businesswoman,” quoting her directly:

“We have built something here no one can take away — not land, not money, but dignity.”

X. The Discovery of 2024

When Amelia unveiled her exhibition at the American Legacy Museum — Hidden No More: The Story of Clara Freeman and the Long Gloves — more than 400 people filled the gallery.

The centerpiece was the photograph, restored and illuminated beside an enhanced forensic scan revealing the faint scars beneath the gloves. Visitors moved between awe and silence.

“Clara Freeman did not hide her scars because she was ashamed,” Amelia told the crowd. “She hid them because she refused to let them tell her story. She chose to show the world what she built, not what was done to her.”

Dorothy, Clara’s great-great-granddaughter, spoke next. Her voice wavered only once.

“When Clara was asked near the end of her life if she regretted hiding her scars, she said, ‘I wanted the world to see what we built, not what they tried to break.’ Tonight, we see her — truly see her — at last.”

Applause filled the hall. Some wept openly. Others simply stood before the photograph, whispering Clara’s name.

XI. The Ripples

The exhibition ran for eight months, drawing more than fifty thousand visitors. Newspapers called it “the photograph that made history breathe.” Teachers brought students; descendants of other enslaved families came searching for connections.

Letters poured in. One, from North Carolina, included a photograph of another woman taken in 1880 — also wearing long gloves.

“My great-grandmother was enslaved on the same Hartwell plantation,” the writer explained. “I never understood the gloves until now. She, too, chose how to be seen.”

Clara’s story had unlocked others. Across the country, families began re-examining old photographs, wondering what secrets might lie beneath lace, silk, or shadow.

XII. The Curator Alone

One evening, long after the museum had closed, Amelia stood alone before the photograph. The gallery lights dimmed, the only illumination coming from the soft glow surrounding the image.

She thought of Clara’s life — born in bondage, scarred in body, unbroken in spirit. She thought of the gloves that had hidden pain and revealed power. And she thought of the note that had started it all: Please tell her story.

She whispered to the photograph, “We did.”

In the quiet, she imagined the river of history running backward through time — from the 2020s to 1875, to the Hartwell fields, to the rustle of chains being broken. And she saw Clara standing there, arms covered, head high, the camera flashing once to capture not a victim, but a victory.

Epilogue: The Gloves

In the months after the exhibition, the museum established the Clara Freeman Research Fellowship, funding scholars who study the resilience of enslaved and formerly enslaved women.

Amelia’s essay in American Historical Review argued that photographs are not just reflections — they are negotiations. Every choice of clothing, every gesture, every shadow is part of a dialogue between survival and self-definition.

Clara Freeman had understood that instinctively.

In 1875, she looked into a camera that had so often been used to catalogue property or to caricature her race — and she made it bear witness to her humanity.

Her gloves, once a concealment, became a monument.

And as schoolchildren now gather before her portrait, whispering questions about freedom and fear, the curator sometimes smiles and answers quietly:

“She hid her scars so that you could see her strength.”

News

Husband Humiliated His Wife in Court — Until Her Mother Walked In and Left the Entire Court Stunned | HO

Husband Humiliated His Wife in Court — Until Her Mother Walked In and Left the Entire Court Stunned | HO…

Florida Preacher Divorces His Wife After Their Wedding When He Caught Her On Diapers With A Big P@nis | HO

Florida Preacher Divorces His Wife After Their Wedding When He Caught Her On Diapers With A Big P@nis | HO…

A Texas Wife Found Out After 10 Years That Her Husband Used To Be A Woman & Shot Him Dead | HO!!

A Texas Wife Found Out After 10 Years That Her Husband Used To Be A Woman & Shot Him Dead…

Teen Smiles in Court, Thinks Family’s With Her — Until They Speak | HO!!

Teen Smiles in Court, Thinks Family’s With Her — Until They Speak | HO!! She reached out to true crime…

63 Year Old Melissa Sue Anderson Finally ADMITS What Michael Landon Did Behind The Scenes | HO!!

63 Year Old Melissa Sue Anderson Finally ADMITS What Michael Landon Did Behind The Scenes | HO!! This wasn’t just…

55 Year Old Pregnant Mother Sh0t 10x By Her Son After Finding Out Who Her Baby’s Father Was | HO!!

55 Year Old Pregnant Mother Sh0t 10x By Her Son After Finding Out Who Her Baby’s Father Was | HO!!…

End of content

No more pages to load