It Was Just a Portrait of a Smiling Boy — Until Historians Discovered He Was Born a Slave | HO

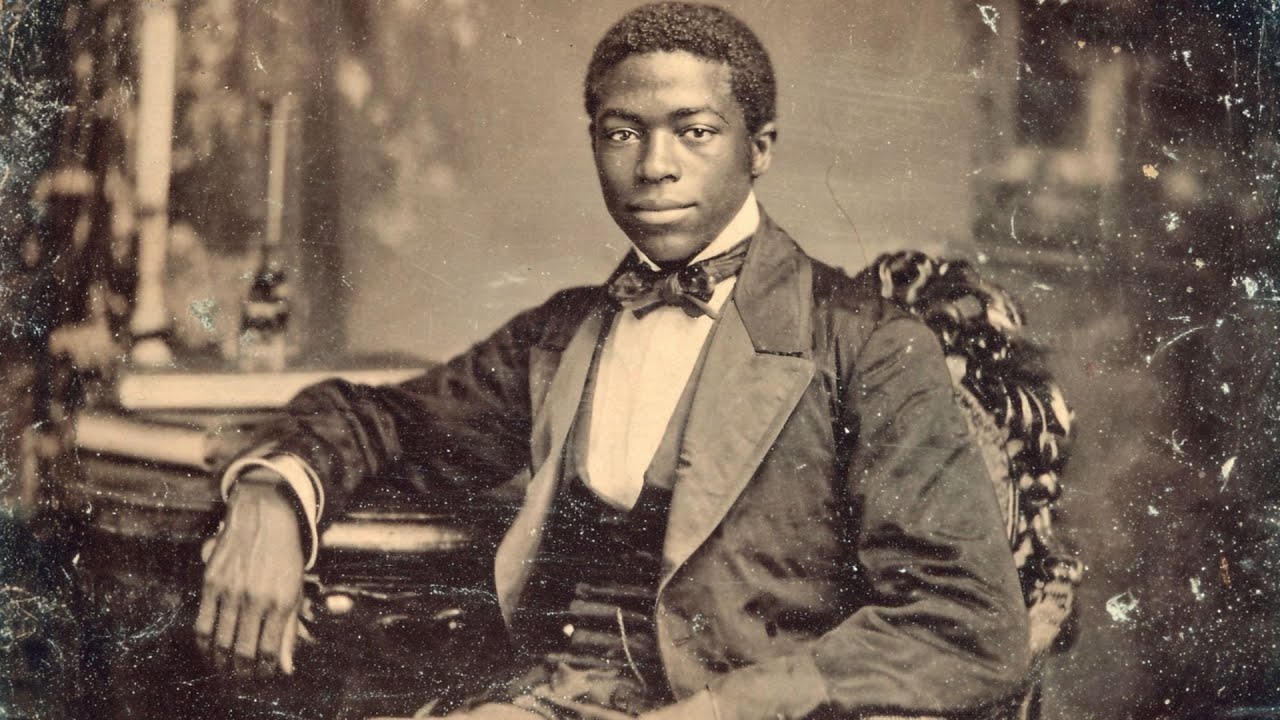

PART I — THE PORTRAIT

In the winter of 1852, a renovation crew working in the attic of the Sorrel-Weed House—a sprawling Greek Revival mansion overlooking Madison Square in Savannah—made what seemed, at first, like a routine discovery.

A canvas wrapped in muslin, tucked behind a trunk of unused shutters.

When the covering was removed, the room fell silent.

The portrait was of a young Black man, early twenties, handsome, well-dressed in a dark coat and pressed collar—attire reserved for white elites in the antebellum South. He wore a small, practiced smile. Not forced, not joyful. Something in between.

But it was the inscription in the bottom corner, written in discreet brown ink, that halted the workers:

Elijah Brown — Property of the Winston Estate.

In 1852, an enslaved person being painted in formal portraiture was nearly unheard of. Portraits were reserved for the wealthy: heirs, planters, merchants. Those who commissioned oil paintings wanted to immortalize lineage and status—not the enslaved individuals they legally owned.

So why had this boy been painted at all?

The Sorrel-Weed caretakers, confused by the anomaly, logged the portrait into storage as Portrait of Unknown Young Man, with no ceremony, no interpretation. Savannah had plenty of pre-war mysteries; one more artifact in the attic attracted little attention.

It stayed forgotten for more than twenty years.

The Historian Who Asked the Wrong Question

In 1873, Thomas Hardwick—architectural historian and meticulous researcher—visited the Georgia Historical Society while preparing a book on Savannah’s antebellum estates. While photographing artifacts, he paused in front of the portrait.

Hardwick later recorded in his journal:

“His eyes unsettled me. Not sorrowful. Not submissive. More like someone evaluating me. A look a man wears when he understands more than he reveals.”

He asked the archivist about the inscription “Property of the Winston Estate.”

No one knew the name.

That question became the first tremor in a century-long unraveling.

Hardwick traveled to the old Winston property—seven miles west of Savannah, a once-grand plantation now collapsing under poverty and neglect. The original Winston family, crushed financially after the Civil War, had sold the property piecemeal.

Inside a decaying outbuilding, he found it: a leather-bound slave ledger.

On page 37:

Brown, Elijah

Male, age 23

Born on property to Martha (deceased)

Educated as experiment

Aptitude exceptional

Value: $800

The phrase “educated as experiment” was extraordinary.

Teaching a slave to read or write was illegal in parts of the South and aggressively discouraged everywhere. Yet Elijah had been trained deliberately—taught numbers, letters, formal bookkeeping.

Why?

Hardwick read further.

October 1851:

“EB demonstrates extraordinary facility with numbers. Maintains secondary ledgers independently. Experiment appears successful.”

December 1851:

“EB asking questions about his mother. Becoming too aware of circumstances. Must temper education with reminders of station.”

The plantation owner—Francis Winston—had effectively created a child accountant. And then started to fear the consequences.

Hardwick wanted testimony from someone who remembered Elijah. He got more than he expected.

The Woman Who Remembered the Boy Behind the Smile

During his third visit to the property, Hardwick met an elderly woman, Sarah Jenkins, who had worked in the Winston household as a child. Her recollection was sharp, specific, unprovoked by suggestion.

“Mr. Elijah wasn’t like the others,” she told him. “Master Winston brought him in the big house when he was seven. Said he had ‘a look,’ like he understood things.”

Winston, she said, taught Elijah himself.

“By fifteen, that boy was running all the books. Calculatin’ faster than men with schooling. Master Winston showed him off—made him do tricks. But when folks left, that smile of his… gone. Eyes got quiet. Like he was thinking too hard.”

Then she added something Hardwick documented word for word:

“Master made him practice that smile for weeks before the painter came.”

A slave forced to practice smiling—because his portrait was about to be painted.

But why immortalize him at all?

Sarah Jenkins told Hardwick the painting was Winston’s “proof”—his argument that, through training, a slave could approach white intellectual capability. A profoundly condescending experiment, even by the standards of the era.

What neither Winston nor the painter knew was that Elijah had begun keeping something else: a second set of books.

Books that would eventually ruin the Winston family.

Books that may have cost Elijah his life.

PART II — THE VANISHING

On August 17, 1852, the Savannah Republican ran a small advertisement:

Runaway. Educated negro man, answers to Elijah, age ~24. Reads and writes. $100 reward for return to Winston Estate.

The notice ran three weeks, then stopped abruptly.

But the truth—revealed later in Winston’s private diary—was far more disturbing than a simple runaway case.

Elijah never escaped.

The Secret Ledgers

After Hardwick found the plantation ledger, he combed through county tax records, bank correspondence, and shipping receipts. A pattern emerged—one that had been invisible for a century.

From 1849 to 1852, Winston’s finances showed dozens of small “errors”:

over-reported losses

under-reported sales

duplicated payments

phantom expenses

Each individually subtle. Collectively catastrophic.

Cross-checked by modern accounting, the discrepancies suggested deliberate manipulation—by someone with exceptional numerical ability and intimate access to the books.

Hardwick concluded Elijah had been siphoning wealth away from the plantation. Not to steal for himself—there was no evidence he profited—but to destabilize a system he recognized as oppressive.

He was weakening Winston financially.

Quietly. Brilliantly. Over years.

That was when Winston began calling Elijah’s education a “mistake.”

The Final Months

Winston’s diary, which Hardwick found locked in a separate chest, painted a man unraveling:

August 20, 1852:

“Necessary to report E as escaped. The truth too dangerous. Have confined him to the old storage cellar. Must determine next steps. His secret writings… alarming.”

August 25:

“His ledgers reveal discrepancies over three years. He denies wrongdoing. Claims the numbers ‘speak truths neither master nor law can silence.’”

September 10:

“Servants claim to hear him at night. Impossible. Door remains bolted. Yet new calculations appear in my study. How?”

October 3:

“The matter with E resolved. Cellar sealed. Portrait to be removed. Sarah dismissed.”

No crime was recorded.

No burial.

No trial.

No evidence Elijah was ever seen alive again.

A runaway ad had been a smoke screen.

Elijah Brown vanished into the same system that claimed ownership of his body.

The Collapse of the Winston Family

Within months:

Winston’s accounts were frozen

his debts were called in

land was sold in distress auctions

creditors sued

business partners abandoned him

By 1853, Winston left Savannah in disgrace, moving to a small property near Augusta. He died a few years later, financially ruined.

Hardwick’s review of the bank letters uncovered a blunt assessment:

“The inconsistencies in your submissions suggest deliberate misrepresentation. Immediate explanation required.”

Hardwick wrote in his notes:

“It is possible Elijah exposed a network of financial fraud far larger than Winston himself. If so, multiple families may have had motive to silence him.”

But without Elijah’s body or confession, no one could prove a crime.

No one wanted to.

The South of 1852 had no interest in elevating an enslaved man into the role of victim—or whistleblower.

PART III — THE AFTERMATH

The Room Beneath the House

In 1873, before leaving the estate for the last time, Hardwick insisted on re-examining the basement levels. He noticed an oddly thick wall and a sealed wooden door. The caretaker allowed it to be pried open.

Inside was a small room—ten by eight feet.

Empty.

Except for a desk pushed against the far wall.

Inside its drawer were carved writings, done with what appeared to be a nail or splinter of metal.

Hardwick copied the legible sections:

“Three years I have watched and recorded.”

“Numbers reveal what words hide.”

“The adjustments are complete.”

“He will not understand until too late.”

These were not supernatural messages.

They were the words of a man documenting the only battlefield available to him: the ledger books.

The carvings were evidence of obsessive, desperate writing—likely done while Elijah was imprisoned.

Hardwick believed the carving stopped abruptly when Elijah was removed from the cellar.

He feared the reason.

The Portrait’s Disappearance

The painting resurfaced once—in 1927—for three days.

Visitors described “unease,” “a disturbing smile,” or “a sense the subject knew something unpleasant.” But these were emotional reactions, not supernatural claims.

The real mystery was logistical:

Why did Elijah’s portrait disappear after 1964?

Hardwick’s research suggests two plausible explanations:

1. Theft

Artifacts of enslaved individuals were undervalued, but private collectors sometimes stole such items, especially if they hinted at scandal.

2. Quiet destruction

Multiple plantations destroyed records and physical evidence related to slave education, interracial parentage, or financial wrongdoing during restoration eras. Someone connected to the Winston line—or its creditors—may have removed it.

A historian later wrote:

“The disappearance of the portrait parallels the disappearance of the man. Both were inconvenient truths.”

Reevaluating Elijah’s Life Through a Modern Lens

By the late 20th century, Elijah Brown’s name resurfaced among scholars researching:

enslaved literacy

plantation accounting systems

slave resistance through economic sabotage

coerced “experiments” in intelligence

psychological manipulation and identity erasure

A 1998 symposium paper described Elijah as:

“A uniquely documented example of intellectual resistance—where knowledge became a weapon, and the ledger a battleground.”

The portrait had been the plantation owner’s attempt to display power.

But the ledgers were Elijah’s attempt to reclaim it.

What Likely Happened to Him

Historians examining Winston’s diary, the sealed room, and the timeline have reached a sober consensus:

Scenario 1 — Elijah died in confinement.

The “sealed” cellar matches descriptions of improvised below-ground holding rooms found on several plantations.

Scenario 2 — Elijah was killed to silence him.

His manipulation of accounts—exposing Winston’s negligence or fraud—may have threatened more than one family.

Scenario 3 — He attempted escape while weakened and died nearby.

Savannah papers reported several unidentified deceased enslaved men found in rural areas during the early 1850s.

None were tested. None were recorded beyond vague descriptions.

CONCLUSION — THE SMILE WE COULDN’T FORGET

The tragedy of Elijah Brown is not his mysterious disappearance.

It is what his portrait—and his ledgers—reveal about the world that owned him.

He was:

a child taught to read for exploitation

a young man praised for intelligence yet denied humanity

an accountant whose brilliance threatened the very system that educated him

a person whose disappearance was covered with paperwork, silence, and lies

His smile in the portrait—once interpreted as eerie, unsettling—becomes, in this historical context, something else entirely:

Defiance.

Understanding.

A private truth held behind the mask he was forced to wear.

A historian wrote in 2001:

“Elijah Brown was never meant to be remembered.

But the ledger remembers him.

And so does the portrait—even if the portrait is gone.”

Today, Savannah’s archives list him simply as:

Elijah Brown (1829–1852?)

Enslaved bookkeeper, Winston Estate

Disappeared under suspicious circumstances.

It was just a portrait of a smiling boy.

Until historians discovered he was born a slave—and died for knowing too much.

News

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was Heartbr | HO!!

56 YR Woman Died Left A LETTER For Her Husband ”They Are Not Your Kids” What He Did Next Was…

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She | HO!!

After Spending All Their Savings On An OF Lady, He Went Ahead To 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛 His Wife, But She |…

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!!

Everyone Accused Her of K!lling 5 of Her Husbands, Until One Mistake Led To The Shocking Truth | HO!! They…

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club & Sees | HO!!

Dad And Daughter Died in A Cruise Ship Accident – 5 Years Later the Mother Walked into A Club &…

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was.. | HO!!

2 Years After She Forgave Him for Cheating, He Gave Her 𝐀𝐈𝐃𝐒, Leading to Her Painful 𝐃𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡 – He Was…..

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her. Why? | HO!!

She Nursed Him For 5 Yrs Back To Life From A VEGETABLE STATE, He Paid Her Back By K!lling Her….

End of content

No more pages to load