Known as ‘The Black Widow,’ she became the cruelest punishment her masters faced in 1845, deep South | HO~

I. The Whisper on the Coast

Along the South Carolina coast in the late 1850s, there were names that people did not say out loud. “The Black Widow” was one of them.

Not Black Widow somebody, not Mrs. anything — just the name itself, spoken the way people spoke of ghosts, curses, or divine retribution. In Charleston County, her name existed somewhere between rumor and religion, between the fear of superstition and the fear of justice.

The county sheriffs knew her only through patterns: a string of deaths, one after another, stretching back nearly thirteen years. Plantation owners whispered about her in courthouse meetings, pretending they didn’t believe, pretending the string of sudden deaths and disappearances was coincidence — yet none dared travel alone after sundown.

The name had its own gravity. They said she had widowed seven white men. Plantation owners, overseers, and slave catchers — all men who had brutalized, enslaved, or profited from human suffering — and all of whom had died mysteriously after crossing her path.

Like the spider that shared her name, she was patient, precise, and merciless. She never struck in haste. She struck when her targets felt safest. And when she struck, it was always without warning.

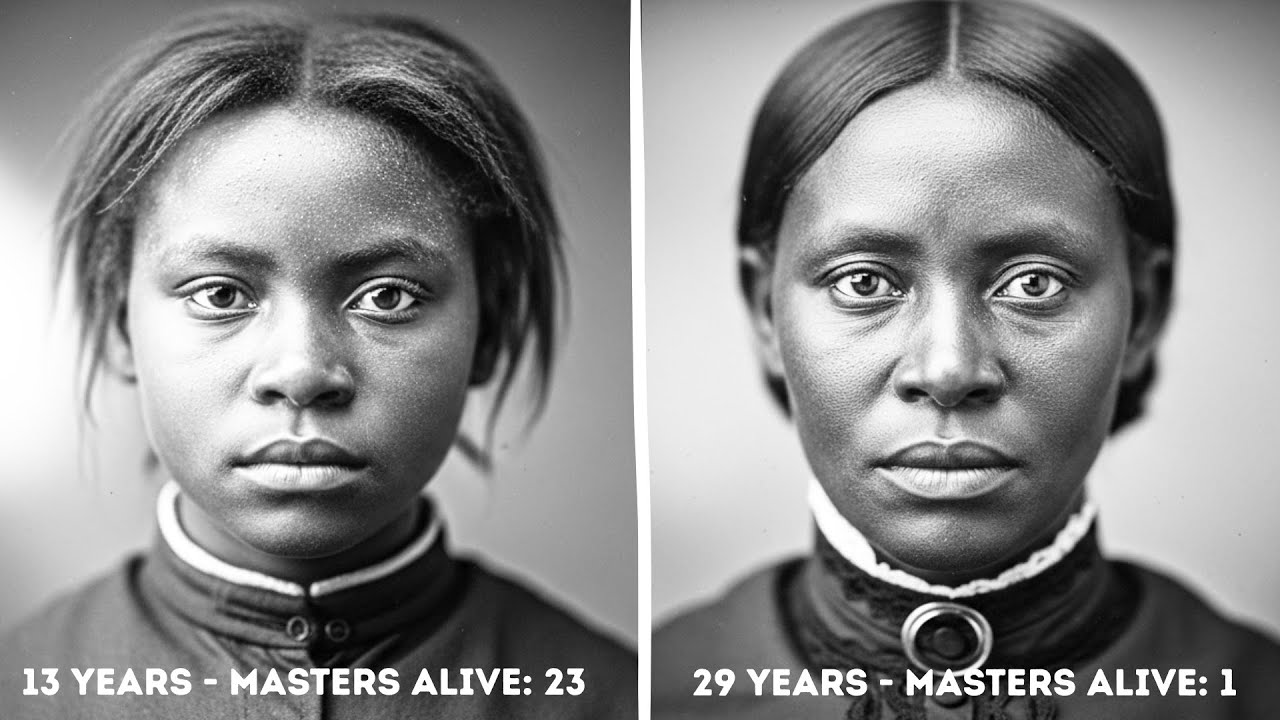

The numbers alone were staggering. In 1838, twenty-three plantation owners ran the vast rice estates between Charleston and Georgetown — men who sat on county boards, wrote laws, and defined morality in their own image. By 1854, only one of those original twenty-three remained alive.

The deaths had official explanations: drowning, fever, accidents, heart failure. Every one of them plausible on its own. Together, they formed an impossible pattern — twenty-two deaths in sixteen years.

To the white elite, the idea that one woman — possibly a black woman — could be responsible for destroying a generation of plantation lords was unthinkable. To the enslaved people along the marshlands, it was the only thing that made sense.

They called her Deliverer in secret, when the night was deep and no overseer was listening. To them, she wasn’t a myth. She was retribution made flesh.

II. Grace and the Birth of Vengeance

She was born Ruth, in 1825, on a rice plantation five miles north of Charleston owned by a man named Thomas Whitmore — one of those plantation lords whose cruelty was disguised as “discipline.”

Her mother, Grace, had been bought at an auction in Savannah two years earlier for $620 — strong, quiet, obedient, the overseer’s reports said. She was the kind of woman who survived by silence.

In March 1845, when Ruth was nineteen, that silence was broken forever.

On a day when the air itself felt like boiling water, Grace dropped a basket of unprocessed rice — fifty pounds at least, too heavy for any one person to carry — spilling grain into the mud. It was a small mistake. But Whitmore was entertaining visitors that day.

To lose control, even for a second, in front of other planters meant losing face. So he turned a minor accident into a public execution.

Fifty lashes, delivered in front of the field hands. Grace did not cry out. She endured it all with the same composure she had used to survive slavery itself. When it was over, her back was a river of blood. She died before nightfall.

The county clerk filed a report: heart failure following discipline.

Whitmore paid five dollars for her coffin and deducted it as a business expense.

Something in Ruth broke that day — but it didn’t shatter. It hardened.

For the next four years, she said little and watched everything. She learned the routines of the plantation, the routes of the patrols, the paths through the marshes that even dogs wouldn’t follow. She memorized every movement of Edmund Calhoun, the overseer who had wielded the whip.

And she learned about poison.

Working under the plantation’s healer — an old woman named Dinah — Ruth learned the names and properties of the plants that grew wild in the marshlands. Which roots soothed fever. Which flowers could kill. She learned that nature’s cruelty could be turned into justice.

In August 1849, four years after her mother’s death, Edmund Calhoun fell ill. His stomach turned, his body weakened. The doctor called it cholera. Ruth brought him soup, wiped his brow, and watched him die over three slow, exquisite weeks.

It was the beginning.

III. The Making of the Widow

When Calhoun’s body was buried, no one suspected foul play. Death came often to the Low Country — fever, infection, accident. But for Ruth, the world had shifted. She had learned how invisible she truly was.

Over the next decade, she perfected her invisibility.

When Whitmore himself died in 1851 — found in bed, heart stopped — no one asked why a man of fifty-six, healthy and wealthy, should die so suddenly. The doctor called it “heart failure.” He didn’t know about the foxglove extract Ruth had been adding to Whitmore’s whiskey for three months.

After the auction, she was sold again — this time to Samuel Crawford, whose plantation was ten miles south.

The move freed her more than it trapped her. Crawford’s property was larger, and his house hosted gatherings of planters from across the coast. Ruth was useful — quiet, skilled with medicines, and invisible. She was hired out to neighboring estates during harvest or illness. Each time, she watched. Each time, she learned.

And each time, someone died.

A planter drowned in an irrigation canal. A pair of slave catchers fell dead from “spoiled oysters.” An overseer collapsed in his field, his heart giving out after weeks of weakness. Every death had a reason. None had a culprit.

By 1854, fifteen of the original twenty-three planters were dead. The sheriff of Charleston County, William Chambers, kept a private notebook. He wrote down every name, every date, and every cause of death. Heart failure. Fever. Accident. Drowning.

He circled the list in red and wrote one word in the margin:

Impossible.

He drafted a confidential report suggesting that “a person or persons unknown, possibly with access to multiple plantations,” was targeting planters. But even that phrasing was dangerous. Admitting that an enslaved woman could terrorize the ruling class would shake the foundation of white supremacy itself.

So the report was buried.

IV. The Widow’s Hunt

By 1855, Ruth was twenty-nine. The plantation world that had killed her mother was crumbling one death at a time. Only one man remained alive from the old circle: Jonathan Prescott, the most feared and most cautious of them all.

Prescott had grown paranoid as his friends died. He surrounded himself with guards. He ate only food he had personally tested. He trusted no one.

But Ruth had learned patience from pain. She didn’t attack Prescott directly. She dismantled his world piece by piece.

One guard died from a snake bite — a snake that Ruth herself had placed. Another died from fever after being swarmed by infected mosquitoes near his quarters. A third fell from his horse after eating fruit treated with a stimulant that made the animal go mad with fear.

By autumn, four of Prescott’s guards were dead. Two remained. Prescott began sleeping with a pistol under his pillow.

Then, in November 1855, he made a fatal mistake. He bought new servants from an estate sale — among them, a quiet woman in her early thirties with calm eyes and a healer’s hands. Her name on the bill of sale was Ruth.

Prescott thought he was buying obedience. What he bought was the end of his life.

For three months, Ruth waited. She learned his schedule. She prepared the oleander — a poison that builds slowly, invisibly, until the heart simply stops.

In February 1856, Prescott died in his bed. The doctor called it “stress-related heart failure.”

The sheriff investigated. He questioned the servants, examined the body, even sent samples of the brandy to Charleston for testing. Nothing. No evidence. No witness. No suspect.

And with that, the count was complete.

Twenty-three plantation owners in 1838.

Zero alive by 1856.

The mathematics of vengeance.

V. The Disappearance

What became of Ruth afterward is uncertain. Some said she was sold again and died in Georgia. Others said she escaped into the swamps and lived out her life as a legend.

A few believed she lived long enough to see freedom in 1865 — an old woman watching the South burn, the world that killed her mother finally collapsing.

The official record stops. But the stories did not.

By the 1880s, former slaves still whispered about her. In letters, sermons, and oral histories, they called her the woman who “made the masters count their dead.”

One of them, a man named Samuel Washington, wrote in his memoir:

“They said she was a monster. But we knew better.

We knew she was a woman who watched her mother die from fifty lashes and decided if no law would punish those men, she would.”

VI. The Legacy

At the South Carolina State Archives, two boxes of documents still exist. In them: death certificates, sheriff’s notes, and a single list written in William Chambers’s own hand.

Twenty-three names. Twenty-three deaths. Dates, causes.

At the bottom, a sentence written years later in a trembling script:

“If this is murder, it is the most successful in the history of the state.

If it is justice, it is of a kind our courts do not recognize.”

No one ever proved anything. But everyone understood.

The Black Widow — Ruth, Grace’s daughter — had done what no army, no rebellion, no law could do. She made the masters afraid.

She showed that power built on cruelty was never safe. That the quiet ones could be deadly. That sometimes, vengeance doesn’t announce itself — it waits, watches, and poisons from within.

And though her name was never recorded in the white histories of the South, her story survived in the one place it could not be erased: the memories of the people she avenged.

Even now, along the salt marshes near Charleston, they say that on certain humid nights, when the rice fields shimmer like glass and the frogs fall silent, you can hear a single woman’s footsteps in the reeds — patient, deliberate, unhurried — as if she’s still walking toward one last name on her list.

The Black Widow of the Deep South: the cruelest punishment her masters ever faced.

News

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis | HO!!

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis |…

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!!

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!! The…

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him! | HO!!!!

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him!…

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!!

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!! For…

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!!

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!! That early fire, unpolished…

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!!

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!! The grass…

End of content

No more pages to load