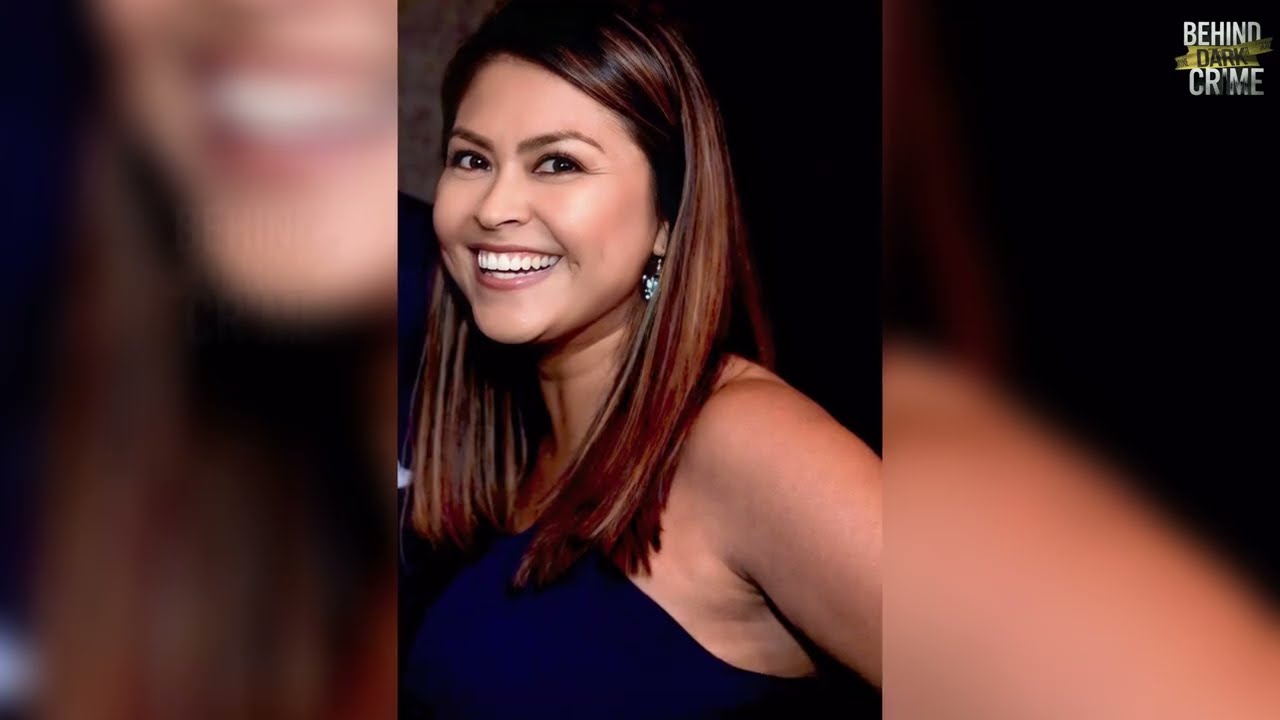

LA Firefighter Husband Reads Wife’s Diary, Grabs Axe & Murders Her | Mayra Jimenez Case | HO

Andrew Jimenez was 45. He’d been a firefighter and paramedic with the Glendale Fire Department since April 2008—seventeen years of service, seventeen years of being the one people call when everything is on fire. Seventeen years of running into burning buildings while everyone else runs out.

He’d recently been promoted. His family posted about it online with pride. He’d just returned from the front lines of the Palisades Fire, saving lives, doing the work people call heroic when they don’t want to think about what it costs.

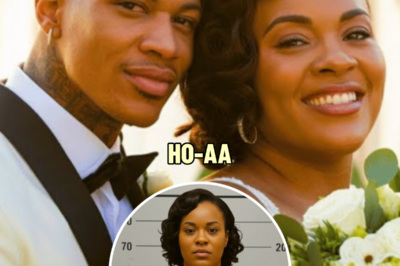

Myra Jimenez was 55. She was a third-grade teacher at Wilshire Park Elementary School in Los Angeles, the kind of teacher students remember long after they forget multiplication tables. Parents described her as fierce for her kids, relentless about making sure every child was seen. When one of her students, a little girl named Sarah, faced health challenges and couldn’t attend school, Myra didn’t just send homework home—she created an entire learning program so Sarah could keep up from home.

She served as a union representative with United Teachers Los Angeles, advocating for better resources and support. Outside of school, she was a non-denominational ordained minister who officiated weddings for couples in her community, standing in front of people in love and saying the words that make vows feel real.

Andrew and Myra had been married since 2014—over a decade. Neighbors saw them walking around the neighborhood on Satsuma Avenue, quiet, kept to themselves. No loud arguments spilling into the street. No obvious warning signs. “There’s never been any violence or any domestic violence or any signs of that at all,” one neighbor would say later. “So I’m really surprised.” They were both Dodgers fans; there was even a photo of them smiling with Vin Scully, the legendary announcer. On the outside, they looked like two professionals with good careers, a nice home, a stable life.

And then, in one night, stability became a crime scene.

*Sometimes the most shocking stories don’t begin with violence—they begin with a person asking for help in the calmest voice they can manage.*

When Andrew walked into the LAPD Northeast Police Station that morning, he didn’t rush. He didn’t confess outright. He didn’t burst into tears or rage. He simply asked officers to check on his wife and mentioned they’d been fighting. The desk officers asked the standard questions: Why? What’s going on? Is everything okay?

Andrew didn’t give much. “We had an argument,” he said, and asked them to go to the home on Satsuma Avenue to make sure she was all right.

He knew what they would find.

When officers arrived at the house and stepped inside, they immediately understood something was very wrong. Detectives who later processed the scene—people who’ve seen too much to be easily shaken—would stand outside afterward saying it was one of the worst scenes they’d witnessed. Blood was everywhere. Myra Jimenez was dead, with multiple blunt force trauma injuries. Neighbors would later recall overhearing investigators through open windows.

“I could hear them talking,” one neighbor said. “How horrific it was. How… bloody.”

Another neighbor described it like something out of a horror movie, and the fact that ordinary people reached for fiction to describe it tells you how impossible it felt to fit into reality.

The weapon, police said, was an axe.

And the motive investigators focused on—what set it in motion—was not a robbery, not an unknown intruder, not a random act. It was something that started as paper and ink.

A diary.

Somewhere along the line, something changed behind that front door. Maybe it was the long hours Andrew worked. First responders have some of the highest divorce rates in the country, partly because the job is designed to pull you away—24-hour shifts, longer during emergencies like wildfires. You come home exhausted, carrying images you can’t easily explain, and you’re expected to flip a switch and be present. It’s not easy. Maybe Myra felt alone. Maybe she felt neglected. Maybe she sought connection somewhere else—someone available when her husband wasn’t. The public doesn’t know exactly when the affair began or how long it lasted.

What investigators did say is that Myra kept a diary—writing her thoughts, her feelings, the intimate details of her life. And in that diary she wrote about the affair. She likely believed it was private, a place to be honest without consequences, just words on a page no one else would ever see.

But Andrew found it.

We don’t know if he was looking or if he stumbled across it by accident, but at some point on the night of January 14th into the early morning of January 15th, Andrew Jimenez read his wife’s diary and discovered she was cheating. His attorney later put it in a statement to the media: their office was in contact with law enforcement regarding “a diary of the decedent,” apparently read moments before the homicide, that “verified infidelity.”

Moments before.

The attorney’s explanation was blunt in its simplicity: he read it, and for lack of better words, he “lost it.”

That’s the hinge in this case—the moment where betrayal becomes a story someone tells themselves to justify a choice they didn’t have to make.

Andrew had options. He could have left the house. He could have called a friend, called a counselor, called anyone to talk him down. He could have decided the marriage was over and walked away to process his pain somewhere safe. But instead, the argument escalated. Neighbors later said they heard raised voices overnight—the kind of fighting that sounds serious but not necessarily deadly. Not yet.

Then it turned physical, and Andrew picked up the axe.

*There are plenty of ways to survive infidelity; the moment someone chooses violence, it stops being a marriage problem and becomes a life-and-death decision.*

What happened next was a sustained, brutal attack. The details, as described by officials and neighbors who overheard detectives, were so severe that seasoned investigators were visibly shaken. Myra died in her own home, killed by the man who had sworn to protect life professionally and promised to protect her personally.

Afterward, Andrew didn’t flee. He didn’t attempt to stage the scene. He didn’t try to vanish into the city. He left the house and drove to the police station. He asked for that welfare check knowing exactly what it would uncover. He waited as officers went to the home. When they returned with what they found, Andrew was detained.

He didn’t resist.

He didn’t immediately demand an attorney, at least not in the first reports. He had already made his decision. And the evidence, authorities said, was overwhelming: the scene itself, the weapon recovered, the diary that established a clear trigger, and Andrew’s own actions walking into the station to initiate contact.

Detectives processed the house and removed evidence—boxes carried out, items documented. Two large rifles were reportedly removed from the home, though those were not the weapons used. The murder weapon was the axe. And among the items recovered was the diary—the diary that set everything in motion.

For a second time, the diary wasn’t just private writing. It was evidence.

Back at the station, the Glendale Fire Department was notified. Their firefighter and paramedic since 2008, recently promoted, veteran of a major wildfire response, was now a murder suspect. He was placed on administrative leave. The department released a statement offering condolences to the victim’s family and support resources for staff processing the loss.

Andrew was booked for murder. Bail was set at $$2{,}000{,}000$$.

News broke fast. An off-duty Glendale firefighter accused of killing his wife with an axe. The public reaction split in a way that always reveals uncomfortable truths about how people think. Some expressed sympathy for Andrew, framing him as a dedicated public servant who discovered infidelity and snapped. Others were horrified—and asked the question that shouldn’t even be controversial: how do you justify that kind of brutality no matter what you found in a diary?

Betrayal hurts. Infidelity can be devastating. But it isn’t a death sentence. It shouldn’t be.

And the people left with the sharpest grief weren’t online arguing about motive; they were inside a school community trying to explain absence to children.

When news reached Wilshire Park Elementary that Myra Jimenez had been killed, the school community was devastated. The principal sent a message to parents: “We are heartbroken by this loss and many of us are still processing this information as we only just learned of it.” A parent whose daughter had been in Myra’s class wrote a tribute that made Myra real beyond headlines: she fought fiercely for students and coworkers, made sure children were seen, gave her daughter Sarah a voice. Even when Sarah couldn’t attend school, Myra built a program so she could continue learning from home.

That’s who Myra was: a teacher, an advocate, a minister, a person whose work was literally building futures.

And she was taken in a way that left even detectives shaken.

*The cruelest part of domestic violence is how quickly it turns a person’s entire identity into a before-and-after—especially when the “before” looked so normal to everyone else.*

Neighbors kept repeating the same theme: they never saw this coming. A neighbor who’d lived on the block 25 years called it “unnerving,” because nothing like it had happened there. “You never heard anything wrong,” she said. “Everyone’s quiet to themselves. They’ve never had fights or arguments. You would never expect it from him.”

Another echoed: no visible signs, no known history, no restraining orders, no calls that made the block label the house as “that house.”

That’s what made the case so disturbing. There wasn’t a public trail of escalating incidents for outsiders to point to afterward and say, “Of course.” Domestic violence doesn’t always show itself until the moment it explodes. Sometimes it hides inside the most respectable professions, behind the cleanest lawns, beneath the calmest voices.

Andrew’s attorney, Jose Romero, initially scheduled a press conference to address the media, then canceled it at the last minute at the request of Andrew’s family. He walked up to microphones, said, “Per the family request at this juncture,” and walked away. No extended explanation. No attempt at public persuasion. But the earlier statement had already set the defense posture: a diary “apparently read moments before the homicide” that verified infidelity.

That was the anchor they offered: he read it and “lost it.”

But “lost it” is not a legal spell that makes choices disappear.

Andrew had resources. Fire departments and first responder agencies often provide mental health support, counseling, peer programs—services designed because the job is heavy and the trauma accumulates. If Andrew had been struggling, if the long hours and what he’d seen were pressing down on him, help existed. It doesn’t solve betrayal. It doesn’t erase pain. But it can keep pain from turning into catastrophe.

Instead, the case became a grim public example of something communities often refuse to accept until it’s on the news: the firefighter can be the danger. The person trained to save lives can also be capable of destroying one.

The question everyone kept asking was “why,” because the “who” was not in doubt. Why would a 45-year-old firefighter with seventeen years of service, fresh off a major wildfire response, with no public history of violence, do this? The official answer offered through the legal statement pointed back to the diary, the infidelity, the humiliation.

But humiliation doesn’t justify homicide. Hurt doesn’t justify violence. And the moment you pick up an axe, you’re no longer reacting—you’re deciding.

There were consequences that no bail number could measure. Myra’s students would have to learn without her. Parents who trusted her would have to tell their children why Ms. Jimenez wasn’t coming back. Colleagues who worked beside her would have to carry grief into classrooms and staff meetings. And the Glendale Fire Department would have to reckon with the fact that one of their own had become the headline they never want attached to the uniform.

The city was already burned-out from literal fire. Now it had to process another kind of ash—what happens when something violent grows inside what looked like a stable marriage and then erupts.

And at the center of it all—first private, then evidence, then symbol—was the diary.

First, it was Myra’s place to be honest on paper. Then it became the thing Andrew read “moments before,” according to his attorney, the trigger that lit him up. And now it stands as a reminder of something colder than any wildfire: rage is not love, and a profession dedicated to protection doesn’t immunize anyone from being the one people need protection from.

If this case leaves you with a knot in your stomach, that’s appropriate. It should. Because the lesson isn’t that diaries are dangerous or that secrets cause violence. The lesson is that violence is a choice, and it can come from the most unexpected hands—quiet hands, helpful hands, hands people trust.

Myra Jimenez was more than a victim. She was a teacher who changed lives, an advocate who fought for resources, a minister who officiated vows, a person whose work was giving. She deserved better than to have her life ended by the person who promised to love her.

And Andrew Jimenez—seventeen years of service, a recent promotion, the hero narrative—threw away his career, his freedom, and Myra’s future in one night because he couldn’t hold the line inside himself.

*In the end, the diary didn’t kill her—the belief that betrayal permits brutality did, and that belief ruins everyone it touches.*

News

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!!

The Dark Truth Behind the Rothschilds’ Waddesdon Manor and Their ‘Old Money’ Illusion | HO!! So he hires a French…

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE IT? | HO!!

He Abused His 2 Daughters For Over 10 YRS; They Had Enough And 𝐂𝐮𝐭 Of His 𝐏*𝐧𝐢𝐬. DID HE DESERVE…

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!

2 Weeks After Wedding, Woman Convicted Of 𝘔𝘶𝘳𝘥𝘦𝘳 After Her Husband Use Her Car In Lethal Crime Spree | HO!!…

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal | HO!!

She Thinks She Succeeded in Sending Him to Prison for Life, Until He Was Released & He Took a Brutal…

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. | HO!!

He Vanished On A Hike With His Friend — Years Later His Jeep Was Stopped With The Friend Driving. |…

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender | HO

A Man K!lled His Wife At Her Parents’ House After Finding Out She Had Lied About The Baby’s Gender |…

End of content

No more pages to load