Lighthouse Keepers Vanished in 1900 Without a Trace, What Was Left Behind Made No Sense | HO!!

At night the Atlantic should have been cut by a steady revolving beam. Instead, in mid‑December 1900, the Flannan Isles were dark—an absence of light that became an alarm.

A supply steamer approached a speck of rock off Scotland’s Outer Hebrides expecting routine relief and found, instead, a stage already set: a half‑eaten meal, an overturned chair, a silent tower, and three professional lighthouse keepers gone. No bodies. No distress signal. No damaged lantern gear.

Just an unsettling tableau that has lived on for more than 120 years. What made the scene feel so wrong—and why has the explanation remained stubbornly elusive?

The Setting: Seven Hunters in Winter

The Flannan Isles, nicknamed the Seven Hunters, are not hospitable landforms so much as jagged Atlantic interruptions lying roughly 20 miles west of the Isle of Lewis. The largest, Eilean Mòr, rises fewer than 300 feet yet behaves like a vertical bastion against relentless swell.

Before 1900, shipmasters had pleaded for a lighthouse to reduce wrecks on these reefs; construction (approved in 1895) demanded four grueling years of hoisting stone, metal, fuel, food, and men onto ledges that could, in a single gale, disappear under spray.

The finished tower: 75 feet high, crowned with a first‑order Fresnel lens throwing a beam some 24 nautical miles—Victorian precision acting as a surrogate guardian in one of the British Isles’ most exposed posts.

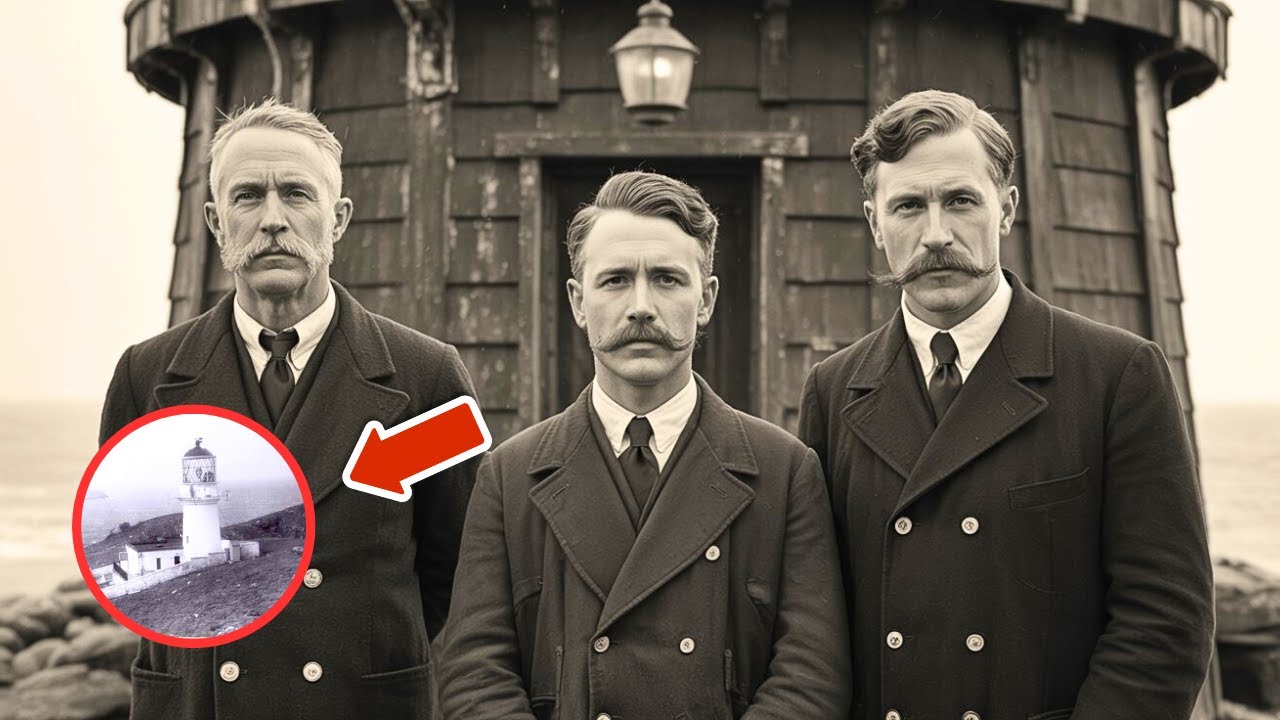

The Men Chosen

Three experienced keepers were on station that December:

Thomas Marshall (principal keeper, 28) – conscientious, methodical, the logbook hand.

James Ducat (often spelled Ducat; second assistant, 43) – long service, calm morale builder.

Donald MacArthur (an occasional or relief keeper, about 40) – physically robust, practical, reputedly capable under stress.

A fourth man rotated ashore under the relief system common to isolated lights. Their lives followed a strict cadence: lamp preparation, nightly tending, meteorological entries, maintenance, meal rotation, and the psychological discipline of routine as insulation against isolation.

Routine—Until It Wasn’t

Supply delivery on December 7, 1900, found all normal. Log entries (considered authentic up to December 13) record standard weather, operational notes, and the brief line: “Storm ended. Sea calm. God is over all.” The pious phrasing is unusual in otherwise technical sheets, yet not impossible for the era.

Sensational later “panic” entries sometimes quoted in retellings (claiming terror of huge seas or men praying) have no firm evidentiary basis; historians now view them as later embellishments.

What is solid: The light functioned as expected until the night of December 15. Passing vessels subsequently reported darkness. Heavy weather in the intervening days delayed official response.

Discovery: December 26–27, 1900

When the Hesperus arrived after Christmas (delayed from the 20th), Captain James Harvey noticed at once: no flag signals, no welcoming keeper, no rotating beam. Relief keeper Joseph Moore landed, climbed the path, and entered an unlocked door. He found:

Kitchen table set; portions of food (often described as mutton and potatoes) undisturbed.

One chair pushed back, another reportedly overturned (the overturned detail appears in some early accounts; its certainty is debated).

Lamp room equipment clean, oil reservoir charged, wicks trimmed—ready for dusk lighting that never happened.

Outdoor storm gear missing for (apparently) two men; one set of heavy oilskins possibly left behind (suggesting at least one man went out inadequately clad if all three left together).

Logbook with last confirmed entry dated December 13. No later official note.

No sign of forced entry, struggle, or interior damage.

Searchers then examined the island. East landing: ordinary. West landing: different story. There, they saw: bent or missing iron railings, a damaged supply box (its contents scattered), mooring ropes displaced and partly coiled up off their usual reels (one report suggests a locker once secured above normal spray height had been wrenched open). These physical clues centered the eventual official theory.

Theories Begin

Rogue (Freak) Wave / Sequential Rescue Scenario

The Northern Lighthouse Board’s inquiry concluded that a violent sea surge or rogue wave struck while one or more keepers were securing equipment at the West landing. A second, then a third, may have rushed outside in breach of the “always one inside” rule, all swept away.

Supporting points: documented heavy Atlantic winter systems; physical storm damage localized at the exposed landing; missing outer garments. Weaknesses: experienced men usually tethered themselves; the lighthouse itself stands high enough that a direct wave reaching the door or drawing all three simultaneously seems improbable without warning.

Modern modeling of wave refraction around steep Atlantic islets shows that constructive interference can create exceptional “set waves” surpassing typical storm height. Steep bathymetry plus swell direction can amplify vertical reach at specific ledges. Thus, an oversized wave (or rapid sequence) clipping men on a deflected spray platform is physically plausible—if they were down there.

Single Accident plus Improvised Rescue

One keeper goes down to secure a box loosened in prior gales. He is injured or swept. A second responds; the first disappears; a third, compelled by urgency and proximity (perhaps thinking he sees a head in foam), leaves the light briefly unattended. Timing plus second surge eliminates all three. This fits human impulse under perceived immediate risk, even against training. Still, it presumes a breakdown of procedural redundancy in disciplined staff.

Sudden Rockfall or Sea-Blown Debris

Atlantic storms can turn unsecured gear into projectiles. A blow from a shifting crane arm, iron hook, or collapsing wooden box could incapacitate one man near the edge. Others attempt retrieval, misjudge footing on algae-slick basalt, and are taken by backwash. Less dramatic than folklore, but consistent with “silent” disappearance and lack of distress signals.

Interpersonal Conflict / Violence

Speculative tales of a fight (sometimes attaching unverified personality anecdotes to MacArthur) gained traction early. Yet: no blood evidence reported, no disturbed interior beyond the meal tableau, and no missing items of value. The island’s sheer edges would theoretically hide bodies, but absence of any ancillary signs (drag marks, tool displacement) weakens this.

External Human Agency (Smugglers / Stowaways)

Given the remoteness, landing unnoticed during rough seas to commit homicide (while leaving everything else pristine) strains probability. No boat sightings, theft, or motives surfaced.

Supernatural / Paranormal / Alien

These persist because they are narrative-satisfying, not evidential. Every physical clue admits terrestrial explanation.

Why No Distress Signals?

The emptiness of flag mast and flare tubes suggests either: (a) No time—event was abrupt and simultaneous for all; (b) Perceived risk was routine maintenance level until escalation; (c) Sequence unfolded away from line-of-sight to signaling gear. A freak wave with a very short onset horizon satisfies (a). A misjudged retrieval task escalating satisfies (b).

Interpreting the “Meal”

Abandoned food evokes cinematic urgency, yet maritime historians caution: Mealtime pauses were often interleaved with weather checks. A keeper might stand abruptly to glance at seas—especially if earlier damage at the landing concerned them. Thus, the tableau, while eerie, may simply freeze a mundane interruption stretched by tragic timing.

The Logbook Myth Layer

Spurious “panic” entries (crying winds, prayers) emerged in sensational press decades later. Accepting them distorts risk assessment; dismissing them clarifies that the last authentic snapshot shows resumed calm after prior storms—possibly prompting a decision to inspect external fixtures before the next incoming system.

Modern Reassessment

Wave pattern simulations for exposed Atlantic rock stacks confirm potential for extreme run-up heights exceeding averaged storm expectations—especially where geometry focuses energy. Combined with empirical records of later documented rogue waves (e.g., Draupner, 1995), the physical cornerstone of the official theory gains retrospective plausibility.

Remaining discomfort stems less from physics than from human factors: Why all three? The answer likely lies in layered micro-decisions: loosening of a box days earlier, perceived lull, underestimation of residual surge sets, a breach of staggered-watch protocol driven by cooperative urgency.

Why It Endures

Mystery persists where evidence is finite, environment hostile to recovery, and narrative elements (isolated rock, vanished triad, silent lamp) invite imaginative fill. The absence of bodies seals ambiguity; the North Atlantic is efficient at permanent concealment.

Most Probable Synthesis

A storm sequence inflicted structural annoyance at the West landing (dislodged box/gear). After weather moderated enough to approach, one keeper descended to secure or inspect. Unexpected large wave (or rapid pair) struck; he was swept or incapacitated.

Two colleagues—possibly without fully dressing—hurried out in succession, were caught by secondary surge or backwash, and lost. The interior, left prepared for routine lamp lighting, fossilized that narrow window between intention and catastrophe.

Legacy

The light continued manned service until automation in 1971; folklore outlived operational relevance. Today the remote, still-working beacon is a technological ghost—automated circuits fulfilling what human vigilance once did at mortal cost.

The “makes no sense” aura dissolves when we map small procedural deviations against an unforgiving maritime system. What remains is less a supernatural riddle than a stark case study in compounded risk at the edge of human occupation.

Standing on any Atlantic cliff in winter, feeling latent force in swell sets that seem placid until they are not, you understand how ordinary judgment can intersect extraordinary water.

The Flannan Isles did not yield a cinematic twist; they offered instead a harsh lesson: the sea keeps time on its own scale, and it rarely returns answers—only warnings for those still keeping watch.

News

Mom Installed a Camera To Discover Why Babysitters Keep Quitting But What She Broke Her Heart | HO!!

Mom Installed a Camera To Discover Why Babysitters Keep Quitting But What She Broke Her Heart | HO!! Jennifer was…

Delivery Guy Brought Pizza To A Girl, Soon After, Her B0dy Was Found. | HO!!

Delivery Guy Brought Pizza To A Girl, Soon After, Her B0dy Was Found. | HO!! Kora leaned back, the cafeteria…

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!!

10YO Found Alive After 𝐊𝐢𝐝𝐧𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 Accidentally Confesses |The Case of Charlene Lunnon & Lisa Hoodless | HO!! While Charlene was…

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!!

Police Blamed the Mom for Everything… Until the Defense Attorney Played ONE Shocking Video in Court | HO!! The prosecutor…

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!!

Student Vanished In Grand Canyon — 5 Years Later Found In Cave, COMPLETELY GREY And Mute. | HO!! Thursday, October…

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!!

DNA Test Leaves Judge Lauren SPEECHLESS in Courtroom! | HO!!!! Mr. Andrews pulled out a folder like he’d been waiting…

End of content

No more pages to load