Master Bought a Pregnant Slave for 12 Cents… Learned the Father Was His Late Brother | HO!!

In autumn 1844, a peculiar entry appeared in the parish records of St. Francisville, Louisiana.

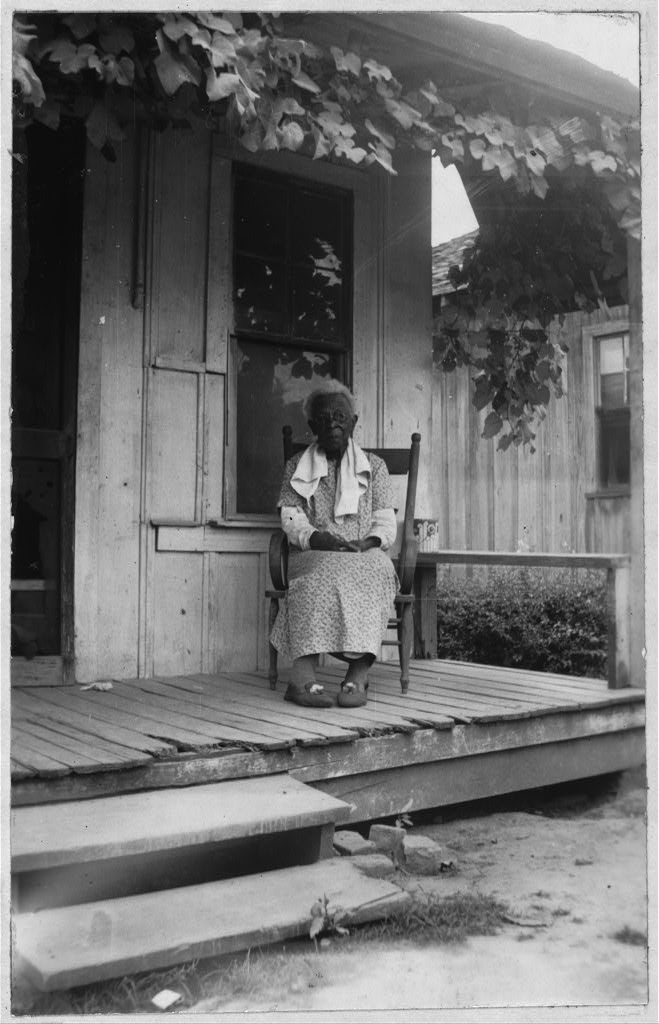

A woman named Claraara Mayfield—enslaved, twenty-five, and five months pregnant—was purchased by plantation owner Henry Duval for the staggering sum of twelve cents.

Twelve cents for a human life.

The price was so anomalous that later historians would puzzle over it for decades. Some called it clerical error, others coded guilt. What no document officially recorded, however, was who the father of Claraara’s unborn child truly was.

That secret—buried beneath generations of silence—would ignite one of the most haunting mysteries in Louisiana’s antebellum history.

The House of Two Brothers

The Duval Plantation, five miles south of St. Francisville, was modest by Louisiana standards. Two stories, white columns, and fields stretching toward the Mississippi. It had passed from Richard Duval—the elder brother—to Henry after Richard’s sudden death that summer.

The official cause: fever. Local whispers suggested a duel.

After the funeral, Henry dismissed the longtime overseer, locked his brother’s bedroom, and spent long nights alone in the library. To neighbors, his behavior looked like grief. To those within the house, it soon felt like obsession.

Among Richard’s papers, Henry found something—letters, perhaps a diary—that hinted at a forbidden relationship between Richard and one of the enslaved women once kept on the estate. Her name: Claraara Mayfield.

Within weeks, Henry set out for Mississippi, withdrew a large sum from the bank in Natchez, and returned with Claraara—pregnant, exhausted, and bought for almost nothing.

The Return of the Unspoken

Henry claimed the purchase was practical—“for household organization,” his ledger reads—but no one believed him.

Unlike others enslaved on the property, Claraara was not sent to the fields. She was placed in the library, assigned to catalog books. The task required literacy, a rare skill for someone in bondage.

From that point forward, the library lights burned late into the night. Servants reported the master’s voice mingling with hers behind closed doors—softly at first, then raised, then silent.

By December, she was near childbirth, and Henry had begun converting the east wing of the house into private quarters—two rooms with fresh plaster and locked doors.

The Birth in the Storm

On January 9, 1845, an ice storm sealed the plantation off from the world. Roads froze, the river crusted in white, and the physician could not arrive.

That night, Claraara gave birth in the east wing, attended only by the cook Martha—and Henry Duval himself.

The child was a boy.

In the family Bible later found among Henry’s papers, the entry reads simply:

“A male child born to Claraara Mayfield. January 9, 1845.”

No name. No father. A blank space where lineage should have been.

Within days, servants noticed changes. Henry ordered fine fabric from New Orleans for baby clothes. He retrieved from the attic the same cradle once used by himself and his late brother.

He called the infant “the heir.”

Madness in the East Wing

By February, gossip spread through the parish. No one saw Claraara or the child. Strange sounds came from the east wing at night—footsteps, crying, voices that seemed to answer one another.

In his fragmented journal, Henry wrote:

“The eyes. The same eyes. Even Martha remarked upon it before I silenced her. He has Richard’s eyes.”

The pastor, alarmed by rumors of “unholy arrangements,” arrived to visit. Henry met him at the parlor door, forbidding entry beyond. The minister later wrote to his bishop:

“There is a darkness in that house that goes beyond sin. I fear for the safety of those within.”

By spring, field hands refused to work near the house after sundown. The new overseer resigned, citing “unnatural disturbances.” Henry began sleeping in a chair outside Claraara’s room, claiming to guard her from the ghost of his brother.

“I hear him in the walls,” he wrote. “When the east wind blows, he calls the boy’s name—the name he has no right to bestow.”

The Will That Should Not Exist

In April 1845, Henry rode to New Orleans. There, he drafted a new will—the most shocking document ever recovered from the Duval archives.

It declared that upon his death, “the male child born to the woman Claraara” was to be freed, educated in the North, and provided a trust. Claraara herself was to be manumitted, given funds to start anew, or—if she declined—to be sold to a household “where literacy and gentle treatment are assured.”

Had this will become public, it would have destroyed the Duval name.

Henry returned with a new household manager, a French governess named Madame Bowmont, tasked with “overseeing the child’s proper upbringing.” For a few weeks, calm seemed to return.

Then Margaret Duval—Richard’s widow—arrived.

“She Knows.”

Margaret stayed only one evening. No record of their conversation survives, but Henry’s journal from the following day repeats one phrase:

“She knows. Or suspects—which amounts to the same.”

That night, he dismissed Madame Bowmont, placed guards at the east wing, and began mapping a route to Texas. Among his papers were travel calculations and supply lists. Notes beside them read: “Move them west—safe beyond reach.”

But before dawn on July 3, 1845, the east wing erupted in flames.

Fire and Ash

Witnesses saw Henry rush into the blaze. None of the three—Henry, Claraara, or the infant—were seen alive again.

When the ashes cooled, authorities recovered three bodies: one male, one female, one infant. The sheriff’s report listed the cause as “accidental fire, likely overturned lamp.”

The community, relieved to close a scandalous chapter, asked no questions.

But decades later, when the Duval house was demolished in 1963, a metal box hidden beneath the floorboards told another story. Inside were Henry’s letters, Claraara’s burned note, and a steamboat receipt dated July 2, 1845—the day before the fire—purchased by Henry Duval for “one woman and infant, passage to Natchez.”

“May God Have Mercy on Both Our Souls”

Claraara’s partially burned letter, written in a graceful hand, read:

“The arrangements have been made as you directed. We will depart before dawn. Your generosity will not be forgotten, though I cannot forgive what brought us here. May God have mercy on both our souls—for what we have done and what we have failed to do.”

If the receipt and the letter tell the truth, then Claraara and her child escaped before the fire—and someone else’s bodies filled their place in the ruins.

The Frenchwoman’s Journal

In 1969, a descendant of Madame Bowmont donated her ancestor’s journal to the Louisiana Historical Society. The entries corroborated the theory of escape.

“Mr. Duval’s mind was divided between guilt and possession. He called the child the last Duval and spoke of cleansing the bloodline. I feared he meant to harm them. The woman Clara confided that he heard his brother’s voice calling him to send the child ‘to join the father.’ Together we planned flight.”

According to Bowmont, she and Martha smuggled Claraara and the infant to the river landing that night. From her window hours later, she saw flames rise—and Henry running away from the house, toward the family cemetery.

“If bodies were found in the ashes,” she wrote, “they were not theirs. Clara and the boy were miles upriver when the fire began.”

Traces Across the Sea

Claraara’s trail did not end there.

A church registry in Cincinnati (1852) lists a “Clara Mayfield Freeman” and her son Richard, described as literate and “arrived from the South.”

Even more tantalizing: baptism records from Liverpool, England (1846) show a Clara Freeman, mother to a fifteen-month-old boy named Richard—born in America.

If it was them, they had crossed an ocean to a country where slavery was outlawed.

The name “Freeman,” chosen deliberately or symbolically, said everything.

The Unearthed Evidence

In 2002, archaeologists excavating the Duval site found the burned foundations of the east wing. Hidden within the charred brick was another metal box containing three objects:

a child’s shoe,

a pocket watch engraved “R.D.”,

and a scrap of paper bearing the words:

“May God forgive what we have done. The truth will in blood and fire.”

Was it Henry’s confession? Claraara’s farewell? A servant’s warning? No one knows.

The Ghost of History

In the decades since, the story of the twelve-cent purchase has lingered through Louisiana folklore. Locals say that on humid July nights near the old plantation grounds, the faint sound of a woman singing a lullaby can be heard—her voice rising and falling with the wind from the river.

Whether ghost or memory, it endures.

The Descendant

In 2022, a young woman visited the Louisiana State Archives, claiming descent from Claraara Mayfield Freeman. She brought with her a small silver locket. Inside was the painted miniature of a man in early-19th-century dress—high forehead, deep-set eyes—and the initials R.D.

“My grandmother said it’s a reminder,” she told the archivist, “of where we came from, and how far we had to travel to be free.”

Before leaving, she stood before the museum case containing the shoe, the watch, and the charred paper.

“Maybe,” she said quietly, “they just wanted to make sure the truth could never be completely buried.”

And perhaps they succeeded.

Because more than 175 years after a man bought a pregnant woman for twelve cents, the fire that consumed the Duval plantation still burns—not in the fields of St. Francisville, but in the uneasy light of history itself, where silence and guilt smolder side by side.

News

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis | HO!!

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis |…

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!!

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!! The…

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him! | HO!!!!

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him!…

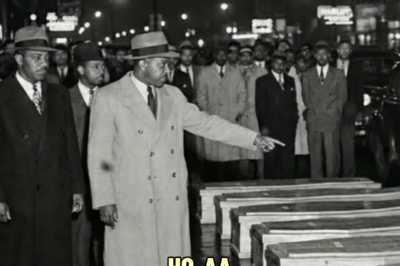

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!!

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!! For…

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!!

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!! That early fire, unpolished…

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!!

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!! The grass…

End of content

No more pages to load