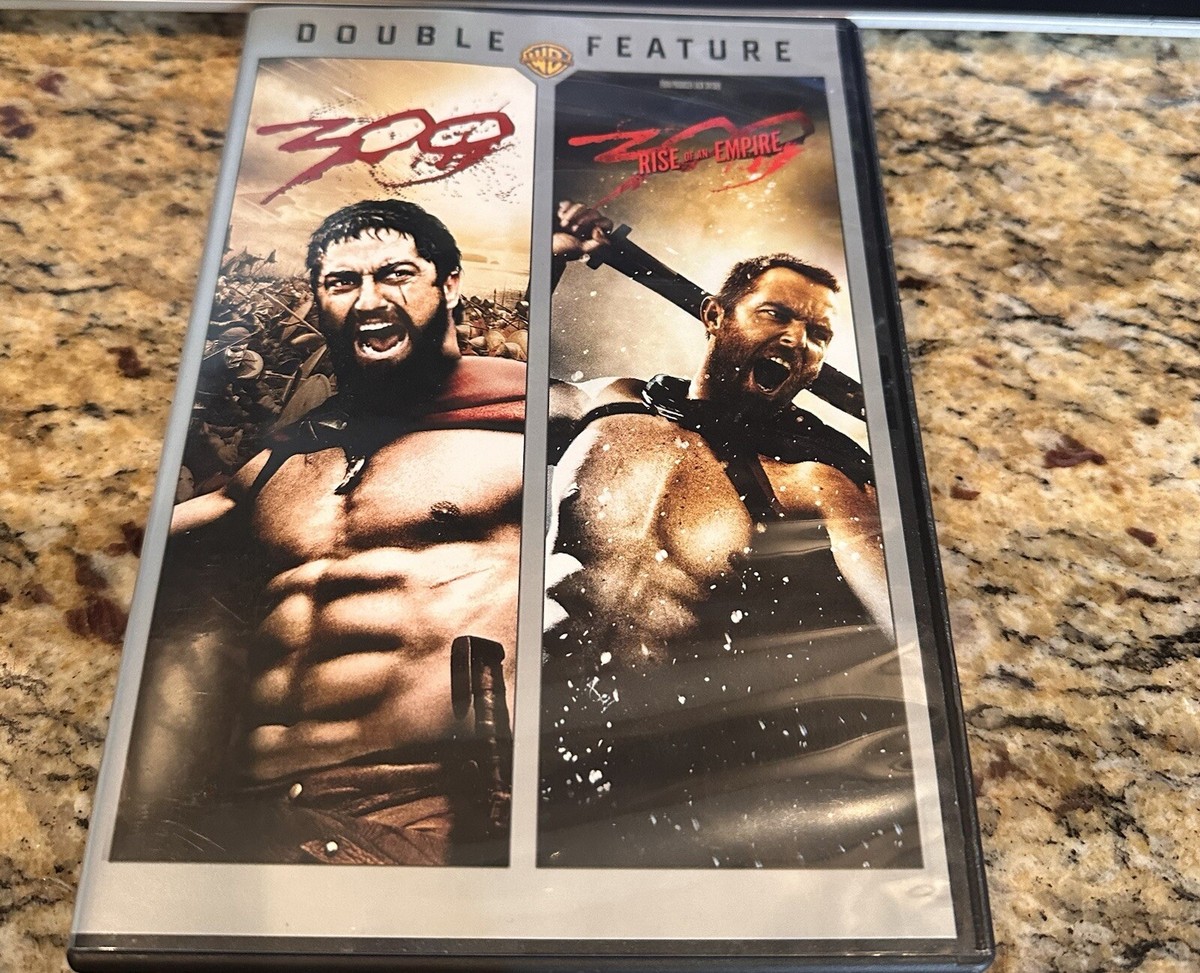

Most People Never Figured This Out About ”300” (2006), Now Gerard Butler Is Finally Revealing It | HO!!

![]()

For almost two decades, audiences treated 300 as visceral spectacle: bronze torsos, stylized mayhem, and Zack Snyder’s graphic‑novel palette blazing onto multiplex screens. What most people never fully grasped, Gerard Butler says now, was how strange, improvisational, punishing—and at times disorientingly empty—the experience behind those images really was.

In early 2025, while promoting new projects, Butler finally framed the shoot not just as a career pivot, but as a physical and psychological crucible whose hidden costs and unorthodox methods helped define modern action filmmaking.

The film opened wide in 2007 (despite shorthand references to “300 (2006)” in fan timelines), but the version the public consumed—digital skies, CG armies, painterly blood—masked a process that, according to Butler’s retrospective account, pushed bodies, imagination, and safety margins harder than most viewers ever suspected.

To understand why he’s talking now, you have to rewind far earlier than the blue screens of Montreal. Butler’s life already carried the texture of reinvention: the Paisley kid whose father disappeared, reappeared when Gerard was 16, and cracked open a dormant emotional vein; the high‑achieving “head boy” who pursued law at the University of Glasgow while moonlighting in a rock band called Speed; the trainee solicitor fired a week before qualifying after self‑destructive drinking spiraled; the suddenly sober twenty‑something who drifted through odd jobs—telemarketing, waiting tables, even selling toys—before fate and audacity landed him in a Stephen Berkoff Shakespeare production. Those detours hardened him long before a stunt spear or tendon strain ever would.

He earned tiny film moments (a blink‑and‑gone submariner in Tomorrow Never Dies, a minor part in Mrs. Brown), then a marquee swing with Dracula 2000 that flopped financially but proved he could anchor a feature.

A brutal physical transformation for roles became a personal toolkit: add muscle, inhabit menace, then turn vulnerable in Dear Frankie or sing unpolished rock‑bar tenor as the Phantom. By the time 300 appeared on his horizon, he wasn’t an instant blockbuster bet—he was a restless composite of theater risk, genre eclecticism, and appetite for immersion.

What separates 300 in Butler’s memory is not just stylization; it’s the vacuum. The production erected a minimal physical world—platforms, ramps, a dirt patch—inside Montreal’s Ice Storm Studios (now defunct), then wrapped it in monochrome emptiness (blue instead of green to keep the Spartans’ red cloaks vivid in compositing).

Almost everything beyond a few weapons, costumed actors, and isolated set pieces would later be painted in post: cliffs, Persian hordes, storm clouds, arterial sprays. Butler recalls a pervasive sensory disconnect: you lunge at phantoms, bark rallying cries at matte codes, die in slow motion surrounded by…silence.

Shooting largely in narrative order (a rarity) provided continuity of emotional fatigue, but didn’t grant the tactile escalation real landscapes give.

Into that emptiness stepped Mark Twight, the mountaineer‑turned strength architect whose training ethos treated actors like an alpine assault team.

Four months of punishing metabolic circuits, barbell complexes, kettlebell lifts, tire flips, rope pulls, and scarcely repeated sessions forged a visible, cohesive unit. The now‑mythologized “300 workout”—25 pull‑ups, 50 deadlifts (135 lbs), 50 push‑ups, 50 24‑inch box jumps, 50 floor wipers, 50 single‑arm clean and presses (36‑lb kettlebell), 25 final pull‑ups—was, Butler notes, a one‑off benchmark, not a daily ritual.

Its purpose: stress inoculation and earned camaraderie. Only a fraction of participants completed it as prescribed; scores were posted; competition sharpened edge. Twight’s randomness—never letting the cast predict the next torment—kept nervous systems in permanent adaptation mode, amplifying both physical transformation and mental volatility.

Physical strain bled into injury. Butler has now detailed a tendon tear, hip flexor issues, nerve irritation (foot drop symptoms), and the cumulative exhaustion of choreographing collisions in armor while dehydrated under studio heat.

Stunt coordinator and double Tim Connelly became more than a safety net—he embodied Leonidas’s father in flashbacks, a meta layering of mentor/trainer both on set and on screen. Butler credits Connelly’s presence with shoring up sequences when his own mobility faltered.

Then there’s the mythology of blood. Fans frequently cite 300’s “gore” as emblematic of a mid‑2000s stylized brutality wave, yet Butler emphasizes how little practical carnage existed on the floor: reportedly only a small volume of actual fake blood (the majority of sprays, mists, streaks, arterial fans rendered digitally later).

That paradox—real injuries, simulated viscera—still unsettles him. The danger wasn’t in sticky squibs; it was in timing a shield hit half a beat off, in a dulled spear glancing near an eye, in cumulative micro‑traumas while the monitor playback would later explode with synthetic crimson.

Costuming choices fed narrative clarity amid the chaos. Historical Spartans wore plumes widely, but Snyder isolated a black crest for Leonidas.

In a sea of cloned digital or near‑identical torsos, that obsidian arc functioned like a visual homing beacon for the viewer and for editorial rhythm—a pre‑CG anchor you could cut around, an emotional compass in kinetic blurs. Replica helmets with that single dark plume still circulate online, a totem less of militaristic accuracy than of cinematic problem‑solving.

Butler’s 2025 reflections also contextualize what followed: the compressed leap from hyper‑aestheticized warfare to the tonal whiplash of P.S. I Love You; the near mishap firing a prop gun while inverted on Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life; the clipped metal suspender that struck Hilary Swank mid comedic scene; a post‑300 surf accident while filming Chasing Mavericks that later fed a painkiller dependence he addressed in rehab; bee venom therapy gone wrong during Geostorm fallout; the loss of his Malibu home in the Woolsey Fire; visible philanthropic work with Mary’s Meals; the continuing, sometimes scrutinized, oscillation between mid‑budget actioners (the Has Fallen series, Den of Thieves entries) and attempts to swerve genre expectations.

Each episode reads differently when you trace its root stress lines back to a formative project where exertion, identity, and public image merged so ferociously.

Crucially, Butler isn’t framing 300 as a cautionary tale of malpractice; he’s framing it as a liminal experiment whose hidden labor recalibrated his internal gauges.

The set’s daily grind legalized a new baseline of suffering for “authenticity” while the final film—its painterly abstraction inseparable from the actors’ carved silhouettes—convinced studios that stylized carnage plus mythic male camaraderie sold globally. That template echoed through a decade and a half of action aesthetics.

What he seems eager to clarify now is that behind the viral memes (“THIS IS SPARTA!”), behind the gym posters and cosplay helmets, sat a sustained act of imaginative projection in a void—actors conjuring dread, awe, bravado against blank chroma emptiness—and that the psychological toll of performing conviction without environment still lingers.

So the “thing most people never figured out” isn’t a single secret injury or a lost scene; it’s the layered disparity between what 300 appears to be (sun‑drenched cliffs, endless armies, operatic bloodletting) and how it was manufactured: disciplined bodies straining in an echoing box, safety always one mistimed beat from breach, courage sometimes meaning claiming uncertainty and pushing through anyway.

Butler’s late candor doesn’t demystify the movie; it reframes its myth—not as a story about superhuman warriors, but about craftsmen wagering their limits to fabricate a legend inside a vacuum, then living with the unseen receipts long after the digital dust settled.

News

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load