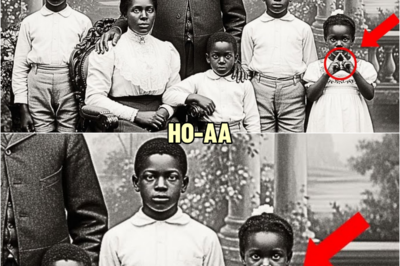

(Photo 1851) Family Portrait Shows 12 People… Only the Slave Midwife Knew Which Children Were… | HO

I. The Photograph That Lied

In 1851, on a stretch of Louisiana land bordered by cypress trees and the slow-moving Mississippi, a photograph was taken that appeared to capture perfection. Twelve figures stood before a mansion whose white columns gleamed under the sun. At the center, a man in a tailored coat; beside him, a woman in lace and pearls; around them, ten children arranged in careful order from eldest to youngest, each frozen in the stillness required by the long exposure of early photography.

The daguerreotype was meant to immortalize the Westfield family — proof of prosperity, lineage, and moral order. It did all of that, at least for those who saw only what the camera was supposed to show.

But a photograph can reveal and conceal at the same time. Even in black-and-white, some things refuse to stay buried: the slight differences in the children’s faces, the tension in the mistress’s jaw, the ambiguous tones of skin.

What the world would not know — not for another 170 years — was that this image hid a crime so intimate and systematic that even time tried to forget it.

Only one person alive in 1851 knew the full truth.

Her name was Dina, the enslaved midwife who had delivered every child in that photograph, whose own hands had caught their first breaths, and who carried the weight of knowing exactly who they really were.

II. The Woman Behind the Births

Dina was about forty-five when the photograph was taken. Born in Virginia, sold south to Louisiana as a teenager, she had been purchased by Jonathan Westfield in 1822 “for her skill in midwifery.” For nearly three decades, she attended births not only on the Westfield plantation but on neighboring estates.

Her body bore the marks of hard labor; her mind carried knowledge that could have destroyed reputations. She had seen everything — the wives who bled in childbirth, the girls forced into motherhood, the silent exchanges between master and slave that birthed children who lived double lives.

At Westfield, her role was both indispensable and unbearable. She delivered children into two worlds — one gilded, one chained — and then was forced to watch as the boundaries between those worlds blurred in the cradle.

In 2019, a team of historians would find Dina’s hidden diary inside a false wall of a slave cabin on what had once been the Westfield plantation. Written in a mixture of English, African dialects, and coded symbols, the diary documented not only the births she attended but the terrible pattern that defined them.

It revealed that at least four of the ten children in the 1851 photograph were not the mistress’s children at all. They were the master’s offspring with enslaved women on his own plantation — children of rape, disguised as heirs.

III. The Architecture of a Lie

To understand how such a deception could flourish, one must understand how slavery functioned not only as labor exploitation but as a theater of appearances.

By the 1830s, Jonathan Westfield was among the most successful planters in the parish. His mansion overlooked 2,000 acres of cotton and nearly 200 enslaved people. His wife, Catherine, was from a Charleston family that prized decorum above all else. Theirs was a marriage of wealth, not affection.

When Catherine nearly died giving birth to her third child, doctors warned she must bear no more. But Jonathan wanted a house full of children — not out of love, but out of image. A large white family was proof of virility, dominance, divine favor.

That was when what Dina called “the arrangement” began.

Whenever one of the enslaved women became pregnant by Jonathan — Rachel, Mary, Hannah, Esther, Chloe, Judith — she was quietly moved into domestic service. Catherine would retreat from public view, pretending pregnancy. When the child was born, Dina attended both births — the real one in secrecy, the false one in society. The baby would then be placed in the mistress’s arms as if she had delivered it herself.

The biological mothers were sent away — to distant fields, to neighboring estates, or sold altogether. The newborns were baptized under forged names. Local doctors and priests signed papers without questions, and the town looked away.

Everyone knew. Everyone pretended not to.

IV. The Children in the Photograph

Each of the ten children in that photograph had a story Dina recorded with painful clarity.

William, 14, the eldest, was truly Catherine’s son — the only one destined to inherit openly. Margaret and Thomas were hers as well, born through dangerous deliveries that left her sterile.

But the next seven — Caroline, Elizabeth, James, Robert, Sarah, Daniel, and Emily — were born to enslaved women whose names were never meant to be remembered.

Rachel was seventeen when Jonathan forced her into his room. Her daughter, Caroline, was taken from her arms within hours of birth. Rachel was sent to the distant fields and later sold.

Mary delivered twins, Elizabeth and James, after a brutal labor that nearly killed her. She was punished for attempting escape and sold to Alabama.

Hannah, the cook, bore Robert, and had to watch him grow up at her own table — a son she could feed but never call her own.

Esther, bought in New Orleans for her light skin, gave birth to Sarah, then stopped eating until she died.

Chloe, born into Westfield slavery, delivered Daniel while singing in the old language of her ancestors. Jonathan kept her close enough to see her son, far enough never to touch him.

And Judith, newly purchased, bore little Emily — a child light enough to “pass.” Within two weeks of delivery, Judith was gone, sold to Texas.

Dina wrote each birth down in code: dates, names, symbols for pain, symbols for silence. She created a secret map of bloodlines the world insisted did not exist.

V. The Weight of Knowing

Dina’s diary is not a dry ledger. It’s a confession, an act of rebellion, a woman trying to keep her soul alive inside an evil machine.

“I deliver children into lies,” she wrote in 1843. “The mothers cry, the mistress pretends, and the master sleeps sound. The children grow up believing what they are told. But I know. And knowing is a burden heavy as iron.”

Her notes trace the moral decay of everyone in that house. Catherine, the mistress, grew pale and brittle. Her letters reveal a woman torn between complicity and despair. “My house is full of lies,” she wrote to her sister. “There are days I cannot tell which children are mine by body and which by duty.”

Jonathan, meanwhile, refined the system. He bribed doctors for false records, paid priests for unquestioned baptisms, and ensured county clerks created perfect paperwork.

Each signature, each certificate, was a nail sealing truth inside a coffin of respectability.

VI. The Community of Silence

Westfield was not an anomaly. It was part of a network of plantations bound together by mutual complicity.

Dr. Marcus Thornton of New Orleans, who attended Catherine, kept ledgers showing large “consulting fees” from families with suspicious birth records. Father O’Brien, the local priest, baptized “miracle children” every year without once asking why the mistress of Westfield appeared pregnant so often yet never seen in church during her supposed confinements.

The parish clerk, Samuel Foster, recorded contradictory dates without hesitation. His private diary, discovered in the 1980s, includes the chilling line:

“We all know what we know and choose not to know what we know. This is the way of things.”

Neighbors mirrored the pattern. At church socials, women whispered about “delicate domestic arrangements,” coded language for the exploitation everyone tolerated.

This wasn’t a secret conspiracy. It was something worse — a collective agreement that truth was dangerous and that white supremacy depended on silence.

VII. Cracks in the Portrait

By the mid-1850s, the fiction began to unravel.

William, now in college in Virginia, heard rumors that his mother could not possibly have borne so many children. He returned home demanding answers. Jonathan told him the truth in the language of power — that this was “the way of men.”

William’s letters afterward grow darker: “I walk among ghosts wearing my family’s faces,” he wrote. He began drinking, unable to reconcile the man he admired with the monster he discovered.

Meanwhile, in the slave quarters, whispers grew. The older children in the fields began to notice uncanny resemblances to those in the main house. One boy, Samuel, confronted Dina, suspecting he had a half-sister among the “white” children. When he tried to speak to her, he was caught and sold to Texas within a week.

Even the photograph — once a proud symbol — became dangerous. As the children aged, their features betrayed the lie. Catherine wanted to keep it as memory. Jonathan wanted it destroyed.

Then came the war.

VIII. The War and the Reckoning

When Union troops neared Louisiana in 1863, Westfield Plantation began to collapse. Enslaved people fled under cover of night, rowing toward Union gunboats. Among them was Hannah, Robert’s mother.

Her testimony to Union officers survives in federal archives. In a shaky hand, she wrote:

“My boy Robert lives in the big house. He calls me Hannah, not Mama. I birthed him in pain. I fed him in silence. They say he is white. But my blood knows.”

The Union officers filed her account, then forgot it. Justice was busy elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Jonathan burned ledgers and letters in his study. Dina watched through the window and wrote:

“He burns the books that tell our stories. But he cannot burn what breathes.”

When Union soldiers finally arrived, they treated the plantation as another southern ruin. They took supplies, freed the remaining slaves, moved on. The crimes of the Westfield family were left behind — buried under ash and silence.

Before leaving, Dina retrieved her diary, wrapped it in oilcloth, and hid it behind a wall plank in her cabin. She gave fragments of its code to her daughter, Rachel. “Keep this truth,” she told her. “Someday they will need it.”

IX. Aftermath and Disappearance

Jonathan Westfield died shortly after the war. Catherine lived quietly until 1872, her sanity eroded by guilt. William sold the land, drank himself to death in New Orleans.

The children of mixed heritage scattered. Caroline, upon discovering her real mother’s grave, dedicated her life to helping freed people find their lost kin. Others — Elizabeth, Sarah, Daniel — disappeared into whiteness, choosing silence over truth.

Dina lived to see freedom. She died in 1879, surrounded by descendants who called her “Grandma Dina the midwife.” To them, she was a healer. Only her daughter knew she was also a keeper of secrets that could still shatter reputations long after everyone involved was gone.

X. The Discovery

More than a century later, the land where Westfield once stood was little more than ruin and weeds. Then, in 2019, during an archaeological dig led by Dr. Lisa Monroe, a descendant of Dina through her daughter Rachel, a graduate student pried open a section of preserved wall. Inside, wrapped in decaying oilcloth, was a leather-bound book.

Dina’s diary.

Its pages were fragile but legible. The first line written in English:

“I write what must not be forgotten in words that must not be read by those who would destroy this truth.”

It took a team of linguists and cryptographers eighteen months to decode it. When they finished, history shifted.

The diary named every mother, every child, every act of coercion. It described how Catherine faked pregnancies, how Jonathan selected which infants could “pass,” how priests and clerks helped bury evidence.

Most haunting were the personal passages — Dina’s exhaustion, her faith, her rage. “This silence is a violence all its own,” she wrote. “I will not let it be complete.”

XI. Bloodlines Revealed

When the diary was made public, descendants from both sides — white and Black — submitted to DNA testing. The results mirrored Dina’s records with uncanny precision.

Caroline’s descendants matched Rachel’s. Robert’s line matched Hannah’s. The genetic threads Dina had mapped in secret now wove themselves into modern science.

The discovery stunned Louisiana. For some white descendants, it was unthinkable; for others, liberating. One descendant of William Westfield said, “We grew up proud of that photograph. Now we know it was evidence — not of family honor, but of family crime.”

Dr. Monroe published Dina’s Diary: The True Names of Westfield in 2023. It became both a historical document and a moral reckoning, forcing Americans to confront how slavery had blurred the line between victim and kin.

XII. The Legacy of Truth

Today, the 1851 photograph hangs at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Visitors stand before it and read the caption:

“Westfield Family, 1851. Four of these children were born to enslaved women on the plantation. Their identities were concealed for generations. Revealed through the diary of Dina, enslaved midwife, discovered 2019.”

School groups linger longest in front of it. Teachers ask students what they see. Some say “a family.” Others say “a lie.” Both are correct.

Outside, in Louisiana, a memorial now stands on the old plantation grounds. Six bronze plaques bear the names of the mothers: Rachel, Mary, Hannah, Esther, Chloe, Judith. Beneath them, Dina’s words are etched into stone:

“Let someone someday know what was done here.

Let the children know who they truly are.

Let the mothers be remembered.”

XIII. Memory and Reckoning

For Dr. Monroe and the families, reconciliation is not tidy. It is not a photo of smiling cousins meeting across color lines. It is raw, emotional, incomplete.

At one reunion, an elderly white descendant whispered to a Black cousin, “I’m sorry for what my family did to yours.” The cousin replied, “It’s the same family.”

That, perhaps, is the final truth Dina wanted the world to see.

Her diary stands not just as testimony of slavery’s cruelty, but as proof of something more enduring — that truth, even when buried in walls and written in code, has a way of surviving.

The Westfield photograph began as propaganda. Now it is evidence. And the woman erased from it — the midwife who stood behind every birth, who saw every secret, who refused to let the lie outlive her — has finally taken her rightful place in history.

News

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!!

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!! They were freelance cartographers hired by a private land…

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!!

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!! The soil in Morris County held grudges. Settlers who…

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. | HO!!

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. |…

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!!

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!! In those first days, Javon…

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!!

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!! Her…

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!!

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!! The photograph lived in…

End of content

No more pages to load