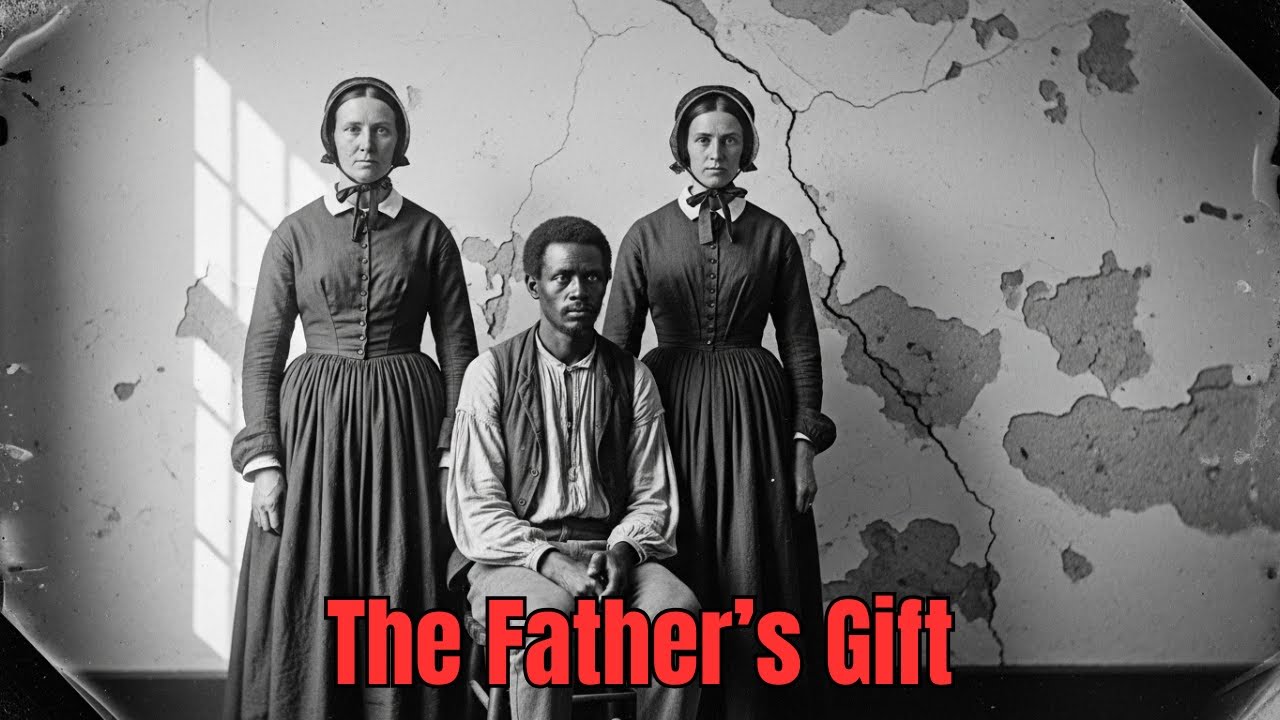

(Photo 1854) Two Sisters Stand Behind the Same Slave in This Photo… Their Father Gave Them Both | HO

I. The Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist

The image was small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, but it carried the weight of generations.

A polished silver plate inside a leather case — a daguerreotype from 1854. Two young white women in hoop skirts stand side by side, their hands resting gently on the shoulders of an African-American man.

Their faces are solemn, frozen in the long exposure of early photography. The man’s expression is unreadable, his posture careful, his gaze aimed just beyond the camera. In the fading light of history, it looked like any other plantation family portrait — except for what was written on the back.

“Caroline and Elizabeth Whitfield with Samuel. Spring, 1854. Both received him from Father as part of their portions. May God forgive what we have done.”

The words were written in delicate, looping ink that had browned with age. The discovery sent a chill through Margaret Chen, an antiques dealer in Savannah, who found the daguerreotype in a box of Civil War–era artifacts at a rural Georgia estate sale in 2019.

She’d handled hundreds of antebellum images before. She’d seen enslaved people posed behind their owners as silent symbols of wealth and status. But this composition was different. Samuel wasn’t standing at the edge of the frame or below the sisters — he was central, almost equal in position.

Chen stared at the inscription again. Both received him. The phrase meant one thing: the man in the photograph had been given to both sisters, not as a servant, but as property.

The last line — May God forgive what we have done — suggested that even someone in the Whitfield family had understood the sin at the heart of the image.

II. The House of Whitfield

In the 1850s, the Whitfield family of Muscogee County, Georgia, was known for its wealth and its quiet cruelty.

William Marcus Whitfield, patriarch of Oakwood Plantation, had inherited 200 acres of cotton fields from his father and built them into 800 by the time the daguerreotype was taken. He was part of a new class of “scientific planters” — men who treated human lives as data points in a profit ledger. He read agricultural journals, lectured on crop rotation, and kept ledgers with meticulous columns of costs and yields.

To neighbors, he was ambitious. To his enslaved laborers, he was calculating.

His wife, Margaret Collins Whitfield, had died of illness in 1848, leaving him with three children — daughters Caroline and Elizabeth, and a son, William Jr. The girls were educated at home by a Charleston governess who taught them piano, French, and the refined stillness expected of Southern women.

They were beautiful, poised, and most importantly, valuable.

In the antebellum South, daughters were as much a financial consideration as land or cotton. Their marriages were business alliances, sealed with dowries meant to maintain the family’s standing. But William faced a problem: dividing his estate between two daughters risked weakening both.

He couldn’t cut the land in half — that would reduce profits. He couldn’t double the dowry — that would drain his fortune. But he could find another kind of asset.

Someone like Samuel.

III. The Man Between Two Worlds

According to fragments unearthed by historian Dr. Helena Foster of Emory University, Samuel was around 23 years old when the photograph was taken. Plantation records listed him not by name, but as “male, 23 — skilled.”

He was more than a field hand. He could read and write — a dangerous gift. He knew carpentry, blacksmithing, and animal care. He maintained the plantation’s tools, repaired carriages, and sometimes supervised younger laborers.

Whitfield once described him in a letter as “a capable fellow for delicate management.”

That phrase — delicate management — was plantation code. It meant Samuel handled tasks too sensitive or valuable to entrust to anyone else. He was trusted, but never free. Useful, but never safe.

When Dr. Foster examined Whitfield’s letters and tax documents, she noticed a shift around 1853. The plantation owner began referring to “a special provision for my daughters’ futures” — a phrase that later appeared in both women’s marriage contracts.

In the spring of 1854, the daguerreotype was taken — almost certainly to commemorate that “provision.”

IV. The Father’s Solution

William Whitfield’s decision was coldly rational.

He would not divide his labor force; he would divide a man.

Each daughter would receive a half share in Samuel as part of her dowry. It was, to his mind, an ingenious compromise: neither girl would feel cheated, and Samuel’s value would bind the sisters together long after they married.

Caroline’s marriage to Thomas Garrett, the son of a neighboring planter, was announced that fall. The dowry agreement, still preserved in Muscogee County archives, listed $3,000 in cash, household furnishings, and — in coded legal language — “half-interest in a skilled male property holder, age approximately twenty-four, to be shared with sister Elizabeth Whitfield per arrangement established by father.”

Elizabeth married Jonathan Pierce, a Savannah merchant, in 1855. Her dowry echoed her sister’s, naming the same “half-interest.”

Dr. Foster, who reviewed hundreds of antebellum dowry contracts, said she had never seen the term half-interest in a human being before. “It’s an extraordinary document,” she told me. “They literally fractionalized a person.”

For Samuel, it meant his life was no longer his own — not even within slavery’s already brutal confines. He belonged to two households.

He would spend alternating months between them: one month laboring on the Garrett farm near Oakwood, the next at the Pierces’ home in Savannah, maintaining their property and managing cargo shipments.

He was not a man anymore, in the eyes of law and family. He was a tether.

V. The Divided Life

Letters between the sisters reveal how Samuel’s existence became an administrative burden discussed in polite handwriting.

“Thomas believes he has been overworked,” wrote Elizabeth to Caroline in 1855. “He arrived ill, distracted, and I suspect you have kept him longer than agreed.”

Caroline replied sharply:

“You forget, sister, that his duties here are heavier, and he is stronger than any man we have. If he appears unwell, it is from the travel, not my use of him.”

For them, his exhaustion was an inconvenience. His pain, a scheduling conflict.

But beneath their letters lay hints of strain. The sisters’ relationship soured as they quarreled over money, over servants, and over Samuel — whose value made him a permanent point of tension.

When Thomas Garrett’s cotton yields fell, he proposed selling “the shared property” to raise cash. Jonathan Pierce refused. “The arrangement stands as Father intended,” he wrote. “Dissolution is neither lawful nor advisable.”

The dispute revealed the trap William Whitfield had set — not only for Samuel, but for his own family. The man who once bound them together now divided them in guilt.

VI. The Vanishing of Samuel

After 1857, Samuel vanished from official records.

He appeared in none of the Whitfield, Garrett, or Pierce ledgers. The 1860 census slave schedules listed a “male, 30, absent — location unknown” in the Garrett household — an unusual note that suggested even the owners didn’t know, or wouldn’t admit, where he was.

What had happened?

Dr. Foster unearthed a series of letters written in early 1862 between Elizabeth Pierce and her attorney, Jeremiah Hullbrook. They had been misfiled in Georgia’s state archives and escaped destruction.

“The situation with Samuel has become impossible to maintain,” Elizabeth wrote. “My sister and her husband refuse further accommodation. Jonathan believes our household must find a different arrangement. The structure Father created troubles my conscience more than I can express. We seek dissolution and disposition.”

Hullbrook’s reply was colder:

“The individual’s current location and condition may present obstacles to transfer. I advise discretion, as these matters are better resolved privately.”

The phrasing — current location and condition — was legal euphemism. It usually meant injury, illness, or death.

In another letter, Caroline wrote to Elizabeth:

“I cannot bear the burden of knowing. Thomas says it was necessary. Father would be ashamed. We must never speak of this again. The photograph should be burned.”

It was not burned. Perhaps Elizabeth couldn’t do it. Perhaps guilt made her keep it — a small, silver confession that refused to vanish.

VII. What the War Hid

When the Civil War broke out, the Whitfields, like many Georgia planters, tried to carry on as if nothing had changed. Their men joined Confederate militias. Their women hosted sewing circles.

The enslaved people of Oakwood waited. Some fled to Union lines when troops came near; others were forced to relocate inland. The war’s chaos destroyed many plantation records — sometimes by fire, sometimes by design.

For Samuel, there were no more records at all.

Then, in a Confederate hospital log from 1862, Dr. Foster found an entry:

“Negro male, approx. 32 years, brought from rural property. Severe injuries consistent with prolonged physical punishment. Unable to work. Abandoned by parties claiming ownership.”

His name was recorded simply as Sam.

The doctor’s note added: Transferred to labor camp after minimal treatment.

If this was Samuel — and every detail suggested it was — his last days were spent in agony, shuffled between ownerships that refused to claim him, discarded into the machinery of a collapsing Confederacy.

Dr. Foster later said, “He was divided in life, and when he broke, they refused to own his suffering.”

VIII. The Grave in the Cotton Field

In 2022, a cemetery preservation group surveying unmarked graves near what had been the Garrett property used ground-penetrating radar to locate a small cluster of burials.

Fifteen graves. No headstones. No records.

One skeleton, a male aged roughly 30 to 35, showed healed fractures, malnutrition, and spinal compression — the markers of chronic abuse.

His grave was shallow, only three feet deep, and contained no coffin, no shroud, no belongings.

It wasn’t a burial. It was disposal.

The bones told a story the letters refused to.

IX. The Historian’s Reckoning

Dr. Helena Foster spent three years piecing the fragments together — the photograph, the dowry contracts, the letters, the hospital log, and the unmarked grave.

In 2022, she published her findings in the Journal of Southern Historical Studies under the title “Divided Property, Destroyed Life: The Whitfield Case and the Economics of Shared Ownership.”

Her conclusion was devastating:

“Samuel’s existence illustrates the extreme logic of slavery — a man so valuable that two families fought to own him, and yet so dehumanized that when he suffered, neither would claim him.”

Some historians criticized the article for lack of absolute proof. But Foster pushed back:

“We build entire biographies of white planters from a handful of letters,” she said. “But when it comes to enslaved people, we demand DNA and eyewitnesses that don’t exist. That double standard is how silence survives.”

The photograph remained the centerpiece of her research — a portrait not of wealth, but of the moment moral decay took form.

X. The Sisters’ Silence

Caroline Garrett died in 1881, leaving behind a faded reputation and a burned-down plantation. No children.

Elizabeth Pierce lived into the 1890s in Savannah. Her descendants said she never spoke of the war, her father, or her sister. She kept a small box locked in her vanity drawer until her death.

Inside were family letters, a child’s bracelet, and the daguerreotype.

When her estate was sold more than a century later, that same image — the one she could not destroy — found its way into Margaret Chen’s hands.

The ink on the back, faint but legible, carried the only confession the Whitfields ever made.

XI. The Photograph Today

Today, the 1854 Whitfield daguerreotype sits in a climate-controlled display case at the Georgia Museum of History.

Visitors lean close, their reflections merging with those of the three figures trapped inside. The sisters’ lace glows under the glass. Samuel’s face remains partly shadowed, as if even light hesitates to touch him.

The museum caption reads:

Whitfield Sisters with Enslaved Man “Samuel,” Georgia, 1854.

This photograph documents a rare instance of shared human ownership between two family members. The man’s fate remains uncertain. The inscription on the back concludes: “May God forgive what we have done.”

Every day, people stop, read, and step back. Some shake their heads. Others whisper. A few cry.

XII. What History Tried to Bury

The story of the Whitfield sisters is not just about two young women and their father’s cruelty. It’s about the moral architecture of a society that made such cruelty ordinary.

The daguerreotype exposes something deeper than ownership — it captures a system that divided even the enslaved from themselves, that turned a man into a thread binding families together through his suffering.

For decades, southern families told stories of noble ancestors and gentle masters. They burned ledgers, altered wills, and polished portraits. But they couldn’t erase every photograph.

Sometimes, history survives not through intention, but through accident — a forgotten box, a note written in remorse, a face that refuses to fade.

Dr. Foster once said, “Photographs like this are not proof of the past. They are witnesses that never stopped testifying.”

XIII. The Weight of a Single Image

If you look closely at the photograph, you can see it — the faintest blur in Samuel’s left hand, where he moved during the exposure. His fingers, clasped tightly, trembled for just an instant.

That tiny motion, captured forever in silver, may be the only visible trace of resistance in a picture otherwise designed to glorify ownership.

Caroline’s hand rests lightly on his shoulder. Elizabeth’s gloved fingers touch his sleeve. Between them, he stands as both man and property, present and erased.

And behind the glass, you can almost hear the whisper written on the back — a confession to God, but also to us:

May God forgive what we have done.

XIV. Epilogue – The Unfinished Reckoning

History rarely grants closure.

Samuel’s grave, if it is his, lies beneath Georgia soil that once grew cotton for the Whitfields. The plantation house is gone. The river still runs past where Oakwood once stood.

Dr. Foster continues her research, now focused on other “divided ownership” cases — fragments of human lives split by inheritance, stitched together by cruelty, and buried by time.

When asked why she keeps studying stories that refuse to end, she said:

“Because the photograph still exists. Because someone wrote those words. Because silence is the last luxury of the powerful — and the rest of us don’t have the right to indulge it.”

The Whitfield sisters, like their father, tried to preserve appearances. But the camera, that mechanical eye, captured something they couldn’t control: the truth.

And 170 years later, that truth has finally stepped out of the shadows, demanding to be seen.

News

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!!

Appalachian Hikers Found Foil-Wrapped Cabin, Inside Was Something Bizarre! | HO!! They were freelance cartographers hired by a private land…

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!!

(1879) The Most Feared Family America Tried to Erase | HO!! The soil in Morris County held grudges. Settlers who…

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. | HO!!

My Son’s Wife Changed The Locks On My Home. The Next Morning, She Found Her Things On The Lawn. |…

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!!

22-Year-Old 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐊*𝐥𝐥𝐬 40-Year-Old Girlfriend & Her Daughter After 1 Month of Dating | HO!! In those first days, Javon…

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!!

12 Doctors Couldn’t Deliver the Billionaire’s Baby — Until a Poor Cleaner Walked In And Did What…. | HO!! Her…

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!!

It Was Just a Family Photo—But Look Closely at One of the Children’s Hands | HO!!!! The photograph lived in…

End of content

No more pages to load