Poor Farmer Saved Two Giant Escaped Slave Sisters — Next Day Slave Hunters Came With Shocking Offer | HO

PART I — The Case Nobody Wanted to Remember

Most stories from the antebellum South survive in ledgers, probate files, or yellowed courthouse minutes written in the stiff, looping hands of nineteenth-century clerks. But every so often, an historian stumbles across something that feels wrong—too strange, too contradictory, too human—to sit quietly inside the fragile boundaries of official record.

This story began the same way.

With three sentences scribbled in the margin of an 1847 civil docket from Knox County, Kentucky:

“Matter sealed by order of Judge Underhill.

Subject concerns two negro women of monstrous stature.

God help us all.”

The docket itself—now brittle, water-stained, and nearly illegible—offers little else. But those three sentences have troubled archivists for more than a century. Because within weeks of that docket entry, three plantation families filed insurance claims for “lost property,” one slave catcher was reported missing in the Appalachians, and a formerly disgraced farmer suddenly paid off years of debt in gold.

The official story is that nothing happened.

The unofficial story is that everything did.

And somewhere between these two contradictory truths lies the forgotten case of Silas Harrigan, a poor farmer whose decision one frost-bitten November morning not only saved two sisters of extraordinary size and strength—but also triggered one of the strangest pursuits in the history of the Kentucky slave system.

Today, historians, genealogists, and amateur researchers still argue about what really occurred. Each camp points to its own sources—scattered family Bibles, oral histories from Black communities near the Ohio River, fragments of charred testimony salvaged from the 1889 courthouse fire.

Every piece is incomplete.

Every witness contradicts another.

And yet all agree on one thing:

Whatever happened on November 14th, 1847, it was not ordinary.

An Ordinary Failure of a Man

Before Silas Harrigan’s name entered the margins of Kentucky legend, he was known simply as a failure.

A farmer who couldn’t farm.

A widower who couldn’t grieve without whiskey.

A Methodist who stopped attending church because he could no longer stand the pitying looks.

His small cabin sat in a narrow hollow twelve miles south of Barbourville, an inhospitable stretch of land locals mockingly called Harrigan’s Hole—a place where sunlight reached the ground only four hours a day and dreams died twice as fast as crops.

For six years the land had fought him.

For three years grief had finished the job.

After his wife Ruth died in childbirth—taking their infant son with her—Silas had collapsed inward like a house with its beams torn out. One by one, every part of his life fell into disrepair: the roof, the fields, the rope well, the vegetable patch, and finally the man himself.

By the fall of 1847 he owed $47 to the dry-goods store.

A staggering sum for a man who barely owned four chickens and a half-wild pig.

Neighbors avoided him.

The Methodist congregation prayed for him.

The local merchant threatened to take him to court.

And Silas had accepted what most men in his position eventually accepted:

He would die poor, drunk, and alone in that hollow.

But Kentucky in 1847 had a way of forcing moral decisions on the very people least equipped to make them. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 meant that every free white man in the state lived—willingly or unwillingly—under a shared expectation:

If you saw a runaway enslaved person, you turned them in.

If you didn’t, you became the criminal.

Even poor whites like Silas, who owned no slaves and never would, had a stake in the hierarchy. Plantation owners didn’t see them as equals—but they preferred them over any Black person, enslaved or free. Aligning with the slave system meant safety. Opposing it meant ruin.

Which is why what happened next makes historians pause.

Because on the raw, frost-white morning of November 14th, the man least likely to defy his own survival saw something impossible emerge from the woods.

And he did not run.

And he did not call for help.

Instead, he opened his cabin door.

The Morning the World Tilted

The frost was so thick that morning it glimmered like crushed glass on every surface. Even the chickens behaved strangely—the rooster silent, the hens huddled tight as if an unseen predator lurked nearby.

Silas stepped out into the cold, nursing the slow burn of cheap whiskey in his throat, fully expecting the same monotonous misery that greeted him every morning. Feed the mule. Patch the roof. Worry about debt. Repeat until death.

He was halfway to the chicken coop when he froze.

Something moved in the tree line.

Too large to be a deer.

Too silent to be a bear.

In the weak morning light, two silhouettes materialized between the black trunks of the forest. And as they stepped into the open, Silas’s first thought—recorded years later in his second wife’s journal—was shock at how wrong his eyes must be.

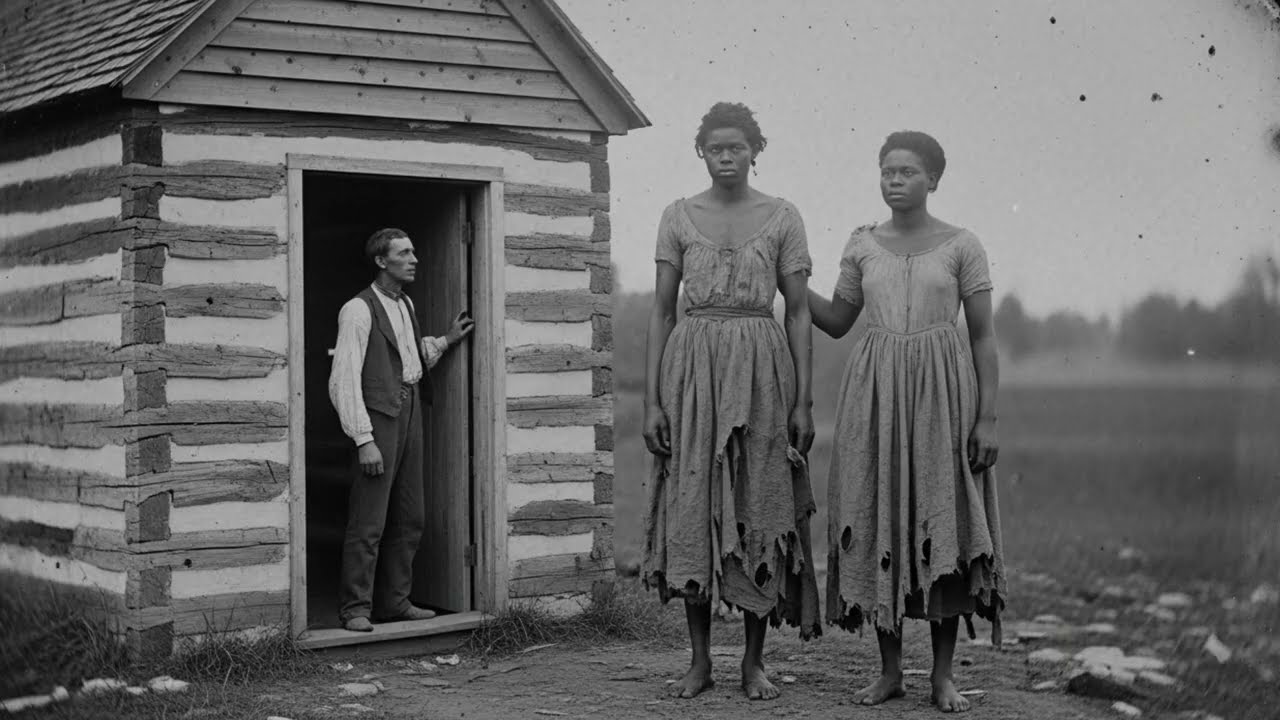

Because the figures were women.

And they were enormous.

Not tall in the way a strong field hand might be tall, but impossibly tall—one around six and a half feet, the other closer to seven. They were barefoot, bleeding, filthy, wearing torn osnaburg shifts usually issued to plantation laborers.

They were sisters.

They were wounded.

They were starving.

And they were runaways.

All three facts hit Silas at once.

The older one—later identified as Clara—held herself upright only through sheer force of will. Her companion, Rose, swayed as if barely conscious. Their backs were crosshatched with fresh and old whip scars.

The taller one’s feet were so ruined they barely resembled human feet anymore.

When Clara finally spoke, her voice was little more than a rasp:

“Water… please.”

Clear, articulate English.

Not the accent of someone newly taken from Africa.

Not the dialect of the Deep South.

Someone raised in Kentucky.

Someone owned by one of the wealthiest families in the state.

In that moment Silas understood two things:

If he helped them, he could lose everything.

If he didn’t, they would die in front of him.

And for reasons historians still argue over, Silas Harrigan chose the second truth.

“Come inside,” he said.

“Before someone sees you.”

The Weight of the Decision

Within minutes, the women collapsed on his cabin floor.

Within an hour, Silas had committed a capital crime.

It wasn’t just offering water.

It wasn’t just letting them rest.

It was the moment he did not ride into town to report them.

He fed them the last of his cornbread, the heel of his Sunday ham, and enough water to pull Rose back from the brink of collapse.

Clara told him the truth in stripped-down pieces:

They had come from the Talbot plantation near Lexington, a sprawling 3,000-acre estate feared across half the state. They were the property of one of the oldest slaveholding families in Kentucky.

Their size—so extraordinary it bordered on myth—had made them both valuable and vulnerable. The Talbots bred horses, but they displayed Clara and Rose with the same pride, calling them “giant stock,” boasting of their strength, parading them before guests.

The family’s youngest son had recently married a woman from Mississippi who demanded Rose as a “conversation piece” for her new household.

Clara would be kept in Kentucky—alone.

They fled the night before the separation.

They had traveled 150 miles in less than a week.

Now Rose was dying.

Clara wasn’t far behind.

Silas listened. He should have thrown them out. He should have saddled his mule and ridden straight to Barbourville. Before dawn, they could both be back in chains and he could be paid handsomely for his “loyalty.”

Instead he found himself saying:

“Rest. I’ll keep watch.”

Historians argue whether this was grief, despair, guilt over Ruth’s death, or simply a breaking point in a man whose life had already collapsed.

But the consensus is this:

Had Silas known who was coming for them, he might not have opened his door.

Because before noon, the slave hunters arrived.

And they did not come quietly.

PART II — The Hunters Who Knew Too Much

The hollow was quiet when they came—too quiet. The chickens had flattened themselves in the dust beneath the coop. Even the mule, usually unbothered by visitors, backed toward the far side of the paddock with its ears pinned flat.

Silas stepped out onto his porch, heart pounding so hard it felt like a second pulse in his throat.

Three riders emerged from the bend in the trail.

Not locals.

Not travelers.

Slave hunters.

And leading them was a man no one in Knox County ever wanted to see: Vernon Pitts, the Talbot family’s personal retrieval agent—part bounty man, part enforcer, and entirely relentless. Other overseers dragged runaways back alive if possible. Pitts returned them any way he pleased.

Behind him rode two professionals:

Hollis Wren, a lean, hawk-eyed tracker known for reading footprints the way ministers read scripture.

Deacon Jones, misnamed, a man whose left cheek bore a scar in the shape of a horseshoe and who preferred using his fists over speaking.

All carried rifles.

All wore expressions of calm ownership—the kind men carry when they believe the land, the law, and God Himself back them.

Silas wiped his palms on his trousers. The sisters lay behind his cabin wall, hidden only by thin pine boards and the fragile hope that the hunters wouldn’t hear them breathing.

The Man With the Ledger of Flesh

Vernon Pitts swung down from his horse with an elegance that didn’t match his broad, squat frame. He wore a wool coat despite the rising sun and carried a small leather book—the ledger that held the names, ages, and prices of every enslaved person on the Talbot estate.

His voice was deceptively polite.

“Mornin’, Harrigan.

Mighty cold for November, ain’t it?”

Silas nodded stiffly.

“Cold enough.”

Pitts smiled without warmth.

“Mind if we trouble you a bit? We’re lookin’ for company.”

He didn’t wait for permission. Pitts walked past Silas as if he owned the land, as if he owned Silas too. The other two followed, their boots thudding against the earth with the slow certainty of men who knew the rules would not apply to them today.

Hollis paused at the woodpile, crouching.

He touched a footprint with two fingers.

Silas’s stomach dropped.

Clara’s footprint.

Huge. Impossible to hide.

But Hollis did not call attention to it. He simply rose, wiped his fingers on his trousers, and stepped onto the porch with the others.

Inside the cabin, Clara and Rose sat in the darkest corner, lungs held still, bodies trembling from exhaustion and fear. Clara’s arm wrapped around Rose protectively, a gesture more maternal than sisterly. She understood that if the hunters looked hard enough, both of them were lost.

“We lost two fine pieces of property.”

Pitts took the chair at Silas’s kitchen table as if it belonged to him.

“We’re lookin’ for two women,”

he began, flipping open his ledger.

“Run off from Lexington two nights ago. Real big ones. You’d have trouble missin’ them.”

Silas forced a shrug.

“Ain’t seen nobody.”

Pitts raised a brow.

“Well now, that’s a disappointment. Talbots are real fond of these ones. Valuable. Special stock.”

He tapped a page with one blunt finger.

“Clara. Strong as a bullock.

Rose, even bigger.

Worth more’n a team of horses.”

Silas swallowed hard.

Pitts leaned in, lowering his voice.

“Now, a man finds ’em?

That man gets six hundred dollars.”

Silas’s breath caught.

Six hundred.

To a poor Kentucky farmer in 1847, that might as well have been a king’s ransom. Enough to buy land, livestock, a future. Enough to erase every debt he carried. Enough to rebuild the life he’d ruined.

Pitts saw the flicker in his eyes.

“We pay cash.

Right then, right there.

No questions.”

Silas gripped the back of a chair so tightly his knuckles whitened.

Behind the thin wooden wall, Rose coughed once—barely a breath, but enough to make Clara clamp a hand over her mouth.

Silas prayed the hunters hadn’t heard it.

The Tracker Who Listened to Soil

Hollis Wren had not spoken once.

He circled the cabin slowly, eyes lowered, jaw tight with concentration. Silas watched him through a crack in the window frame.

Hollis knelt by the edge of the porch.

He brushed aside leaves.

He traced a pattern in the mud.

He pressed his hand to the ground.

Then his head lifted.

He had found something.

Silas felt the world tilt.

Hollis stepped inside the cabin again.

And at last he spoke.

“Someone big came through here.”

Not accusatory.

Not hostile.

Just certain.

Pitts turned.

“How big?”

Hollis met Silas’s eyes.

Then he answered carefully, too carefully:

“Big as a man.

Maybe a hog.

Maybe both.”

Silas blinked.

A hog?

For a moment he didn’t understand.

Then he did:

Hollis was giving him a lie.

A lifeline disguised as an observation.

Pitts frowned.

“A hog, Wren?”

Hollis shrugged.

“Ground’s torn up.

Big prints.

Could be anything.”

Now Deacon Jones stepped forward, looming over Silas, his breath smelling of whiskey and chew.

“You sure you ain’t hidin’ somethin’, Harrigan?”

Silas kept his voice steady.

“Only thing I got hidin’ round here is hunger.”

Jones snorted.

But Pitts wasn’t convinced.

He stepped toward the back wall—the wall behind which Clara and Rose crouched in absolute stillness. His boots moved slowly, rhythmically across the floorboards, each step measuring the space between truth and disaster.

He laid his palm flat against the boards.

Listened.

Silas felt the air collapse in his lungs.

If Pitts heard even the faintest breath…

If Rose coughed again…

If Clara shifted even one inch…

This would turn bloody. Quickly.

But the sisters held perfectly still.

Pitts stepped back.

“Hollow boards,”

he said.

Silas’s mouth went dry.

“Old cabin,” Silas replied.

“Whole place is hollow.”

Pitts studied him.

Too long.

Too knowingly.

Then he smiled the predatory smile of a man who had just made a private decision.

“We’re gonna search your place.”

Silas’s heart slammed.

“We got no cause—”

“I am cause.”

The Moment Everything Hinged On

Deacon Jones shoved Silas aside and made for the bedroom. Pitts strode toward the pantry. Hollis waited by the door, watching Silas—not suspiciously, but with a strange, unreadable heaviness, as though he knew the fate of three people rested on whether he spoke again.

Rose’s breathing grew ragged.

Clara pressed a hand over her sister’s mouth.

Pitts kicked open the pantry.

Jones lifted the mattress.

One of them would check the back wall next.

And Silas would be ruined, jailed, or killed.

The women would be dragged back in chains.

Pitts would collect his reward.

History would forget the moment entirely.

Unless.

Silas made a decision he could never explain.

He reached into the fireplace, grabbed a burning log with a cloth, and slammed it onto his own table, sending flames licking up the edge of the curtain.

Jones shouted.

Pitts spun.

And suddenly the cabin was alight.

Silas shouted:

“Fire!

Put it out before it catches!”

The men rushed toward the flames—stamping, cursing, throwing blankets. Smoke filled the cabin, stinging the eyes, clouding the air.

In the chaos, no one heard Clara slide the back window open.

No one saw Rose struggle to her feet.

No one noticed two ghostly shapes disappearing into the treeline.

By the time the hunters extinguished the fire, the cabin was full of smoke, overturned chairs, and scorched cloth.

Pitts coughed hard.

“Harrigan, you damned fool—

You nearly burned your own house down!”

Silas shrugged, choking on smoke.

“Reckon you won’t be searchin’ more today.”

Pitts glared at him, eyes narrowing.

“We’ll be back.”

But Hollis Wren—

the man who tracked footprints like scripture—

lingered at the door.

He looked at the back wall.

At the window.

At the forest.

Then at Silas.

And for the first time, he smiled.

A thin, tired smile that meant:

You bought them hours.

Not days.

Use them well.

Then he rode away.

PART III — The Night Run That Should Have Killed Them All

Before Hollis and Pitts had ridden out of sight, Silas was already moving. His hands shook from adrenaline, smoke, and the knowledge that he had crossed a line that no poor farmer in Knox County could ever uncross.

He stepped to the back wall, shoved the window open wider, and whispered into the dark:

“They’re gone. Go.”

Then he waited—listening for a rustle, a cry, any sign that the sisters had been caught before their escape truly began.

Nothing.

The forest swallowed them whole.

Silas checked the road again, then shut the shutters tight and began the frantic preparations of a man who knows the law is only a few miles behind him. Every second mattered. Every decision had to be deadly precise.

The Wagon of Bones

Jackson the mule brayed angrily—he seemed to sense the danger. Silas threw the old harness over him anyway, cinching it too tight in his haste.

He dragged the wagon forward, its wheels screaming against dry axles, and packed the bed with old hay and brittle burlap sacks that still smelled of last year’s rot.

Silas whispered into the empty yard:

“Clara. Rose. If you can hear me—come on.”

For a moment he wondered if they had run without him.

If terror had splintered their trust.

If they were somewhere in the hills right now, dying silently under the early winter frost.

Then the underbrush parted.

Not with a snap.

Not with a stumble.

But with a cautious intelligence—a stealth that did not match their massive size.

Clara appeared first, half-crouched, one hand braced against a tree for balance. Her broad shoulders rose and fell with desperate breaths she was trying not to make sound. Behind her, Rose leaned heavily on her sister’s arm. Her feet left smears of blood where she stepped.

Silas swallowed hard.

They can’t go another mile.

How in God’s name are they going forty?

Clara lifted Rose into the wagon herself, as gently as if placing her onto a church pew.

“Don’t look at her feet,” Clara muttered.

“Just drive.”

Silas didn’t look.

He couldn’t.

He helped Clara climb in beside her sister, then buried them under hay, layering it so that even a torchlight would see nothing but a load of dirty fodder.

Clara whispered through the hay:

“We can breathe. Go.”

Silas climbed onto the driver’s plank, snapped the reins, and whispered the prayer of a man who believes he may be heading toward his death but finds that death preferable to cowardice.

The wagon groaned forward.

The Road Through the Throat of the Hills

There is a part of Knox County where the mountains narrow into a single pass—a dark, winding throat of rock and shadow. Locals knew it well. Slave catchers knew it better.

Silas aimed directly for it.

If he stayed on the main road, Pitts would intercept him before he’d traveled five miles. But the hunters believed only fools went into the throat after dark.

Silas whispered:

“Then God make me the biggest fool in Kentucky.”

Jackson balked at the entrance, braying, stamping, jerking against the reins. The mule sensed something wrong—something old and hungry in the rocks above.

Clara’s muffled voice drifted from the hay:

“Animals feel spirits.

Pay attention to him.”

Silas forced a laugh.

“I’d pay more attention if he wasn’t a stubborn demon the rest of the year.”

But he hesitated.

The Throat was a place of whispered stories. Strange lights had been seen there. Travelers reported footsteps following them with no human shape behind them. A missing girl was last known to have entered the pass at dusk in 1832. Her mother swore that her voice still echoed on certain nights.

But the hunters were behind them.

Silas cracked the reins.

They went in.

What the Woods Remembered

Darkness in the Throat wasn’t ordinary darkness. It pressed against the eyes. It felt wet. Heavy. As if something unseen walked just beyond the lantern glow.

Silas had lived his whole life in the Kentucky woods.

He had never felt them watch him until now.

Behind him, under layers of hay, Rose began whispering fevered nonsense—names, prayers, fragments of songs that Silas didn’t recognize. Clara tried to soothe her, but Rose’s voice rose to a distant, eerie wail.

Silas hissed:

“Keep her quiet!”

Clara whispered back:

“She’s hearin’ things we can’t.

When she gets like this—there’s no quietin’ her.”

Silas cursed under his breath.

The path narrowed. Jagged boulders jutted like broken teeth. Jackson trembled as he walked. Silas tightened his grip on the reins, his palms slick with sweat.

Then he saw it—

Light.

Flickering.

Moving.

Not firelight.

Not lantern glow.

Something paler.

Colder.

Silas’s skin crawled.

“Clara… do you see that?”

A pause. Hay rustled.

“Yes.”

“What is it?”

Another pause.

“Not the hunters.”

Her voice was too calm.

Too certain.

Silas swallowed hard.

He didn’t want to know.

The Hunters’ Trap

They cleared the last bend—and Silas’s heart dropped.

Three horses blocked the exit.

Pitts.

Hollis.

Jones.

They hadn’t believed the fire story.

They hadn’t believed Silas’s lies.

They had circled ahead.

Pitts, grinning, tipped his hat.

“Evenin’, Silas.

Fancy meetin’ you here.”

Hollis’s expression was unreadable.

Jones already had his hand on his pistol.

Silas stopped the wagon.

The woods behind them hissed with wind—or something that sounded like wind. Jackson stomped and rolled his eyes.

Pitts rode closer, his boots scraping against the stirrups.

“A man out this late?

With a wagon full of… hay?”

He leaned in.

“Let’s take a look at what you’re carryin’.”

Silas’s heart stuttered.

This was it.

There was no escape.

He opened his mouth—

—when a sound cracked through the woods:

a scream.

Not human.

Not animal.

A shriek that seemed to tear through the rocks themselves.

Pitts’s horse reared. Jones cursed. Hollis’s hand froze on his rifle.

The scream echoed again, closer now, and the air grew cold enough to frost breath.

Silas didn’t waste the moment.

He slammed the reins.

Jackson lurched forward.

The wagon shot past the hunters before they recovered.

Pitts fired—

the bullet splintering the back rail—

but Silas did not stop.

Not for miles.

Not until the first pale hints of dawn bled over the ridge.

News

In Miami Secret Affair Led To 𝐇𝐈𝐕 & 𝐀 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐃!𝐬𝐦3𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐁𝐨𝐝𝐲 | HO!!

In Miami Secret Affair Led To 𝐇𝐈𝐕 & 𝐀 𝐁𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐃!𝐬𝐦3𝐦𝐛𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐁𝐨𝐝𝐲 | HO!! Kendra Bailey ran her hand along…

Military Twin Sister Swapped Place With Her Bruised Sister And Made Her Husband’s Regret His Actions | HO!!

Military Twin Sister Swapped Place With Her Bruised Sister And Made Her Husband’s Regret His Actions | HO!! On the…

17-Year-Old Posts Final Video Before Dying — Taylor Swift’s Response Is UNTHINKABLE | HO!!

17-Year-Old Posts Final Video Before Dying — Taylor Swift’s Response Is UNTHINKABLE | HO!! It was Ava’s idea, even though…

Ex Wife Of NFL WR Tyreek Hill Gets DESTROYED By Judge For Buying $196k BENTLEY & LOSES Support Case | HO”

Ex Wife Of NFL WR Tyreek Hill Gets DESTROYED By Judge For Buying $196k BENTLEY & LOSES Support Case |…

Teen Vanished After Rehearsal in 1983 — 19 Years Later, a Note in His Old Things Revealed the Truth | HO!!

Teen Vanished After Rehearsal in 1983 — 19 Years Later, a Note in His Old Things Revealed the Truth |…

Infant Missing Since 1985 — After 20 Years, One Mismatched Record Reopened the Case | HO!!

Infant Missing Since 1985 — After 20 Years, One Mismatched Record Reopened the Case | HO!! On July 15th, 1985,…

End of content

No more pages to load