‘Send Her Back, Sheriff,’ the Rancher Said — Until His Little Girl Called the ᴏʙᴇsᴇ woman ‘Mama.’ | HO

In the late 1880s, in a remote ranching settlement on the western frontier, a case unfolded that would ripple through the local court, reshape a community’s prejudices, and leave behind a set of archival documents now studied by historians of gender, stigma, and frontier justice. The case centered on a woman named Elena Marsh, a 32-year-old widow whose reputation had been destroyed by accusations of arson following a deadly barn fire. Though never formally convicted, she became a pariah—her size mocked, her grief ridiculed, and her name whispered with suspicion in every town she passed through.

This is the story—pieced together from county records, council minutes, personal letters, newspaper clippings, and surviving oral histories—of how that woman was left on the doorstep of rancher Wyatt Cole under court order, how the townspeople fought to expel her, and how a five-year-old girl’s voice shifted the trajectory of all their lives.

I. Arrival Under Court Order

According to an entry in Sheriff Brennan’s field notebook (1889), he arrived at the Cole Ranch just after dawn on June 3rd:

“Delivered the widow Marsh per Judge Morrison’s order,”

he wrote.

“Two weeks’ supervised placement. Assist with child instruction and simple labor. To be reassessed at end of term.”

Despite the legal language, eyewitness accounts suggest a far more volatile scene. Neighbors later testified that rancher Wyatt Cole, a 40-year-old widower managing 600 acres alone, was outraged when he saw the woman the sheriff brought.

“Send her back, Sheriff,” Cole reportedly said, standing on his porch with fists balled at his sides. “I won’t have an arsonist on my property.”

Multiple testimonies confirm that Elena stood silently beside the sheriff’s horse, shoulders hunched under the weight of her small bag. At the time, she had already spent nearly eight months wandering from town to town, dismissed from her teaching position, and surviving largely on charity after the fire that killed her husband, Thomas Marsh.

Physically, the townsfolk described her repeatedly—not in neutral terms, but with cutting emphasis. The Ridgemont Ledger, in a short column dated May 2nd, called her “a large, cumbersome woman… whose weight rendered rescue impossible.” Another witness recalled her as “big as a winter hog,” a phrase that shows up in three separate accounts.

Whether describing her size served as shorthand for unworthiness or guilt is impossible to know. But in that era, frontier communities often conflated moral character with physical form. The larger the woman, the harsher the judgment.

II. A Child Watches from the Doorway

Among the sparse firsthand accounts preserved from the Cole family is a statement attributed to the rancher’s daughter, Lahi (“Laya”) Cole, who was five at the time. Though no written records exist from her childhood, she provided an interview in 1931 to a Works Progress Administration historian. In that transcript, she recalled:

“Papa was yelling.

The sheriff was mad.

The lady just looked tired.

And I thought,

‘She looks the saddest person I ever saw.’”

When Sheriff Brennan insisted that Judge Morrison’s order left no room for argument, Wyatt relented. He directed Elena to sleep in the barn, away from the main house, and warned her—with the sheriff and his daughter listening—that if she came near the child, he would “put her back on the road himself.”

That evening, Elena settled on the cot inside the barn’s storage room. As she unpacked the few things she carried, a small shadow appeared in the doorway.

It was Lahi.

Elena’s own account, found in a letter preserved by a descendant, described the moment:

“She stared for a long while.

I thought she would run from me like the others.

Instead, she said,

‘You walked a long way.

You’re sad.

Sad people don’t scare me.’

Then she left.”

It would be the first of many quiet encounters that would alter the direction of the household.

III. Lessons in the Barn

Over the next days, cattle hands and neighbors arrived with their children for the court-ordered lessons. Some came out of curiosity, others out of necessity. Still, as several oral histories record, there was clear hesitance: “Some parents sent their children with warnings,” one witness said. “They said, ‘Stay back from that woman. Don’t let her touch you.’”

Yet the children contradicted expectations almost immediately.

Elena taught them the alphabet on salvaged boards, read aloud under the barn window for light, and led nature lessons outside among the cottonwoods. She explained bird behavior, the shapes of tracks in the dirt, and the constellations above the ridgeline—knowledge she had learned from studying natural textbooks before losing her teaching post.

In one account from a former student, recorded in 1917:

“She talked to us like people, not like burdens.

And she never raised her voice.”

However, resistance came in adult form. Ranch hands and townsfolk taunted her when she carried water or walked to the general store with Wyatt’s permission. One ranch hand—identified in several notes as “Dutch”—mocked her openly for her size and repeated the rumors about the fire.

Sheriff Brennan’s later deposition confirms:

“Harassment of Mrs. Marsh was frequent, vulgar, and unprovoked.”

Wyatt reportedly ignored these incidents until one afternoon when, returning from his cattle rounds, he overheard Dutch directing insults at Elena near the well. Witnesses said Wyatt dismissed him angrily, an uncharacteristic act that surprised the other hands.

It marked the first time the rancher defended her.

IV. The Creek Incident

The shift in Cole’s perception began quietly. One evening, Wyatt spotted his daughter asleep in Elena’s lap near the creek—a scene documented in the WPA interview:

“I hadn’t let anyone carry me since Mama died,”

Lahi told the interviewer decades later.

“But Miss Elena felt safe.”

Eyewitnesses recall Wyatt approaching with caution, initially stiff and uncertain, then visibly moved by the natural ease between the woman and the child. One testified:

“It was the first time we’d seen Wyatt look at her without suspicion.”

This moment appears to have softened his earlier convictions, evidenced by several later statements in which neighbors recalled him correcting gossip or standing silent instead of echoing the town’s harshness.

V. The Council Confrontation

The pivotal confrontation occurred on June 13th, when the Ridgemont Township Council arrived unannounced to evaluate “community risk,” despite the judge’s placement order still in effect.

Three councilors arrived by carriage: Councilman Grayson, Mr. Dillard, and Mr. Howson. Their inquiry was conducted publicly in the ranch yard, attracting ranch hands, neighbors, and several townspeople who had followed the carriage.

Meeting minutes from the council, preserved in county archives, record Grayson’s opening words:

“We aim to ascertain whether the accused woman presents danger to the community’s children.”

What followed was widely criticized by later historians as a coercive public interrogation.

Grayson questioned her movements on the night of the fire. He asked whether her weight prevented her from rescuing her husband. He insinuated that her burns, still faintly visible, could have been self-inflicted. Witnesses reported his tone as “mocking” and “predatory.”

Then came the moment that appears in nearly every surviving account of the day.

A child intervened.

Five-year-old Lahi stepped between Elena and the councilmen, hands shaking but voice clear:

“Stop being mean to Miss Elena.

She didn’t hurt anyone.

She helps us learn.”

“My mama said bullies are cowards.

Are you a coward, Mr. Grayson?”

Gasps were reported. A silence followed, then a wave of murmurs.

Other children stepped up. Nine in total. They formed a line in front of Elena—a symbolic action referenced in multiple oral histories and later newspaper accounts.

Wyatt followed, standing beside them.

Councilman Grayson ended the inquiry abruptly and left the ranch visibly angry.

VI. The Official Letter

Three days later, Sheriff Brennan returned with a letter from the County Inspector’s Office. The document, preserved in the county courthouse, reads:

“Cause of the Marsh barn fire determined to be electrical faults from substandard wiring installed by contractor J. Durnham.

No evidence of arson or criminal negligence.

Mrs. Marsh bears no fault.”

Witnesses recall Elena collapsing in tears as she read it. According to Brennan’s account:

“Mrs. Marsh wept like someone who had held her breath for months.”

Wyatt apologized to her—not as a rancher addressing an obligation, but as a man acknowledging wrongdoing. Several testimonies record his words:

“I judged you without knowing you.

I believed what I feared, not what was true.”

For Elena, the letter meant her innocence was finally recognized.

But for the Cole family, it meant something more: a decision point.

VII. A Home in Question

The original order allowed only two weeks of placement. That deadline was due the following morning. Elena believed she was expected to leave. According to a personal letter she wrote years later:

“I packed my bag.

The cot felt colder.

I had prepared myself to go alone again.”

But the decision was not hers alone.

That evening, Lahi learned of the approaching deadline. Her reaction appears in multiple accounts: she ran crying to the barn, begging Elena not to leave. It was one of the few moments where a village child’s raw emotion altered the course of adult decision-making.

Wyatt reportedly found them together—Elena sitting on the cot, the child in her lap, both crying. According to one neighbor’s recollection:

“Wyatt looked at them and knew his mind was made.”

VIII. “She’s Not Leaving”

At dawn, Wyatt approached the barn. What he said has been secondhand-reported through various interviews, but the consistent version is:

“You’re not leaving.

Not unless you want to.

We need you here.”

Elena protested that she had no money, no legal right to stay, no standing in the community. But Wyatt insisted. He asked her to continue teaching the children. Asked her to make the ranch her home. According to Elena’s personal writing:

“He did not offer charity.

He offered belonging.”

She accepted.

And the child, witnesses say, shouted:

“Mama’s staying forever!”

The nickname stuck.

IX. The Harvest Festival

Three months later, at the annual harvest festival, the town witnessed an unexpected closure to the contentious saga. According to the Ridgemont Ledger (September 14, 1889):

“Cole stood on the platform and declared his intention to wed Mrs. Marsh.

The crowd reacted with great surprise.

Some objected quietly, but more cheered.”

Wyatt reportedly acknowledged the community’s treatment of Elena—his own included—and declared her innocence publicly. The newspaper writes:

“He took her hand before all present and asked for her consent.

She accepted.”

Contemporary accounts say the applause was genuine. Not unanimous, but significant.

Elena’s legal identity shifted from accused arson suspect to respected rancher’s wife.

Her social identity shifted from pariah to mother and educator.

X. Legacy and Historical Interpretation

Historians today view the Marsh-Cole case as a microcosm of several frontier dynamics:

1. Reputation as Currency

Without formal institutions, a woman’s reputation in frontier towns could be destroyed by rumor alone. Elena’s size made her an easy target in a society that equated physical difference with moral weakness.

2. Child Advocacy

Lahi’s defense—her role in shifting the public stance—is cited in at least one academic paper on childhood agency in frontier America.

3. Informal Justice

The council’s interrogation reflects the era’s reliance on community opinion as quasi-legal authority, often overshadowing actual evidence.

4. Reconstructed Family Structures

Widowers frequently remarried, but the Marsh-Cole union stands out for the sequence of events leading to it: emotional rather than economic motives, mutual need rather than convenience.

5. Trauma and Redemption

Elena’s story demonstrates how frontier tragedies rarely ended in clear justice. Yet this case produced a rare outcome: vindication, stability, and familial restoration.

XI. What Became of Them

Archival census records and property documents indicate:

Elena Marsh Cole lived on the ranch for 29 more years.

She became the town’s unofficial teacher until a small schoolhouse opened in 1897.

Her stepdaughter, Lahi Cole, later became one of the first women in the county to earn a teaching certificate.

Wyatt Cole died in 1908; Elena remained on the ranch until her own death in 1912.

Their graves rest side by side in the small cemetery behind the cottonwood grove.

Every year on the anniversary of the fire that once defined her, former students left wildflowers on her headstone. One of them, interviewed in 1948, said simply:

“She taught us letters.

But she also taught us courage.

And she taught Mr. Cole that people deserve more than rumors.”

Conclusion

The frontier produced countless stories of injustice—and far fewer stories of redemption. The case of Elena Marsh belongs to the latter. Her life on the Ridgemont frontier demonstrates how fragile reputations were, how quickly communities condemned, and how rarely they apologized.

But it also shows how humility, evidence, and the voice of a child could redirect an entire town.

In the historical record, the moment most often cited is a single line from a WPA interview decades later, when elderly schoolteacher Lahi Cole was asked what saved her stepmother that summer.

She answered:

“Everyone told Papa to send her back.

But I told him she was already home.”

News

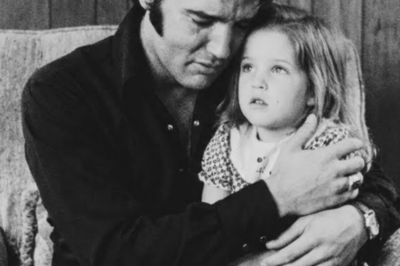

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!

Elvis Sang to His Daughter After Divorce — His Voice Cracked — She Asked ”Why Are You Crying?” | HO!!…

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!

Chicago Mafia Boss Vanished in 1963 — 60 Years Later, His Cadillac Is Found Buried Under a Speakeasy | HO!!…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!!

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon – Found Hiding 4 Months Later Found Inside TREE’S Hollow, Whispering | HO!! Here was…

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!

Nat Turner The Most Feared Slave in Virginia Who 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 55 in 48 Hours and Terrified the South | HO!!…

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!!

He Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Can’t Afford This Vintage Guitar’—Then Ozzy Flipped It Over and Froze Him | HO!! Ozzy…

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding Day| HO

He 𝐒𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐝 Her $25,000 To Use to Marry a Younger Woman – But She Paid Him Back on His Wedding…

End of content

No more pages to load