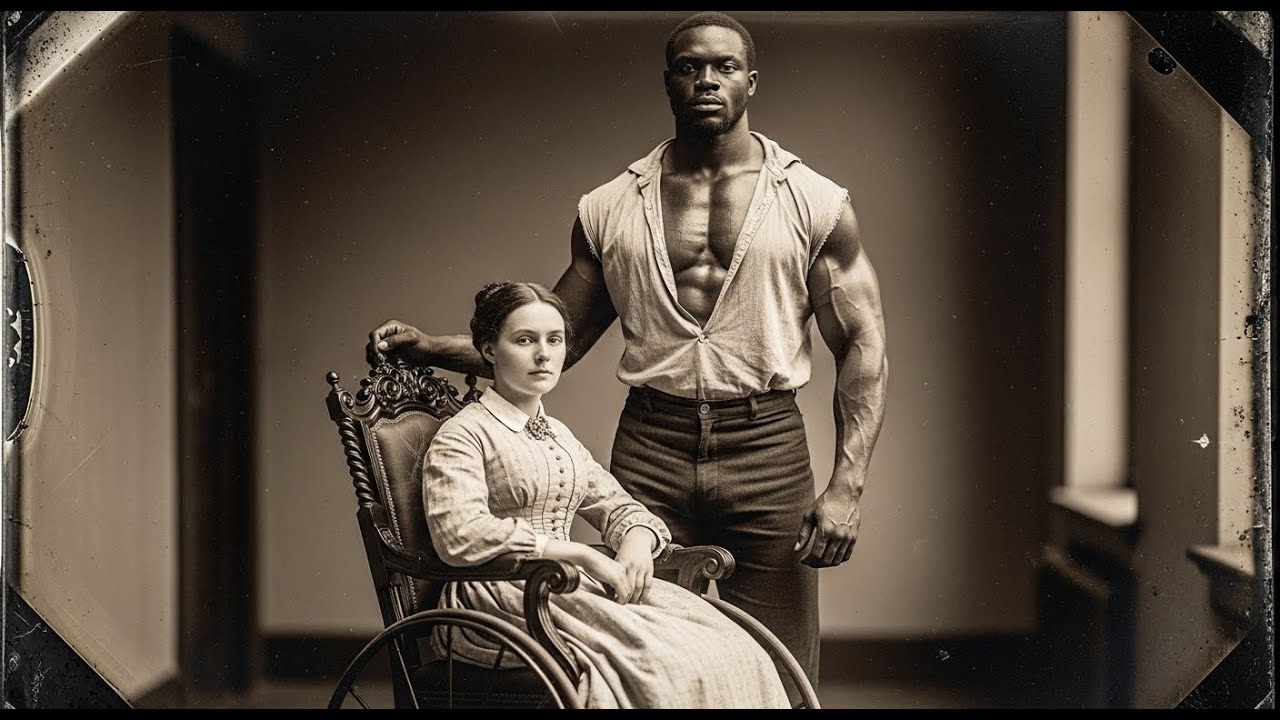

She Was Deemed Unmarriageable—So Her Father Gave Her to the Strongest Slave, Virginia 1856 | HO

In the spring of 1856, in the rolling countryside of central Virginia, a young woman named Elellanar Whitmore—rich, educated, beautiful, and permanently bound to a mahogany wheelchair—heard the same sentence for the twelfth time:

“No man will marry a cripple.”

Twelve suitors in four years had refused her.

Twelve families had whispered that she was “damaged goods.”

And twelve men had looked at her wheelchair before looking away.

But Elellanar’s story did not end there.

Because when society rejected her for the final time, her father—Colonel Richard Whitmore, master of 5,000 acres and 200 enslaved people—made a decision so radical, so socially unthinkable, that it would alter not only Elellanar’s fate, but the fate of a man enslaved under him.

He gave his daughter to the strongest enslaved man on his plantation.

A man rumored to be a brute.

A man feared for his size.

A man whose hands could bend iron.

His name was Josiah.

And what followed became one of the most incredible, forbidden, and transformational love stories in 19th-century America—a story that challenged every assumption about race, disability, marriage, and human worth.

This is the story society tried to erase.

I. The Girl in the Mahogany Chair

Elellanar Whitmore was born into privilege—but privilege could not save her from the accident that changed everything.

At eight years old, a riding mishap shattered her spine.

For the next fourteen years, she lived in a wheelchair made of carved mahogany and brass.

In antebellum Virginia, a woman’s value was measured by:

physical capability

fertility

social presentation

her usefulness to a future husband

A woman who could not walk was, by every cruel standard of the era, a burden.

Doctors speculated she was infertile—without ever examining her.

Rumors spread faster than facts.

And suitors, once polite, grew blunt.

“She cannot produce heirs.”

“She cannot stand at events.”

“My children need a mother who can chase them.”

“She’s broken.”

By 22, Elellanar had endured a lifetime of rejection.

Her father, one of the wealthiest landowners in the region, tried everything.

But even offering a third of his estate’s profits to an older widower—William Foster—was not enough.

Foster refused her.

Even money could not override prejudice.

That night, Elellanar realized the bitter truth:

No white man in Virginia would marry a woman in a wheelchair.

And her father realized something else:

When he died, she would have nowhere to go.

No inheritance.

No legal protection.

No husband.

No home.

And so he devised a plan so shocking, so outside the norms of 1856, that even his daughter thought she had misheard him.

II. The Decision That Changed Everything

Colonel Whitmore told his daughter the truth plainly—because there was no gentle way to say it.

“No white man will marry you,” he said. “But you need protection.”

In Virginia, property and inheritance laws forbade women from owning estates independently.

Upon his death, everything would pass to his nephew Robert—a man with no affection for Elellanar.

Robert would sell the plantation.

Dismiss her.

Ship her to distant relatives.

Reduce her to a dependent.

Her father would not allow that.

His solution:

“I’m giving you to Josiah,” he said.

“The blacksmith.”

Elellanar stared at him.

Josiah, the enslaved blacksmith.

Josiah, seven feet tall.

Josiah, the man people whispered about.

The man visitors called “the brute.”

“Father,” she whispered, “Josiah is enslaved.”

“I know exactly what I’m doing,” her father replied.

He believed:

Josiah was strong enough to protect her

Intelligent enough to manage household responsibilities

Bound by law, meaning he could not abandon her

Gentle, despite his enormous size

It was unthinkable.

Unheard of.

Illegal for any enslaved man and white woman to marry under Virginia law.

But in the confines of Whitmore’s estate, the colonel could arrange something else—an internal union, unrecognized by the state, but fully binding within his household.

Elellanar begged to meet Josiah before her father made the final decision.

Her father agreed.

That meeting would shatter every expectation she’d ever held.

III. The Giant Who Bowed His Head

The next morning, Elellanar heard the heavy footsteps echoing down the hall.

Josiah ducked—literally ducked—to enter the parlor.

He was enormous:

seven feet tall

three hundred pounds

shoulders as broad as a doorway

hands scarred from years at the forge

a presence that made grown men nervous

But what startled Elellanar most was not his size.

It was his posture.

Head bowed.

Hands folded.

Eyes locked on the floor.

Every movement careful, respectful, controlled.

He was a man accustomed to shrinking himself.

Her father introduced them.

“Josiah, this is my daughter, Elellanar.”

He looked at her for half a second—dark eyes meeting hers—then lowered his gaze again.

His voice was soft, surprising, gentle.

“Yes, sir.”

Elellanar asked him the only question that mattered:

“Do you understand what my father is proposing?”

“Yes, miss,” he murmured. “I’m to be your husband. To protect you. To help you.”

“And you’ve agreed to this?”

He hesitated.

The concept of “agreement” for an enslaved man was foreign.

“The colonel said I should, miss.”

Then she asked the question that changed everything.

“But do you want to?”

Josiah looked up slowly.

“I don’t know what I want, miss.

I’m a slave.

What I want doesn’t usually matter.”

Her heart broke.

And opened.

Her father stepped out, leaving them alone.

For the next two hours, they talked.

IV. Shakespeare in the Forge

Josiah could read.

Elellanar discovered this by accident.

When she asked him which books he’d read, fear flashed across his face—reading was illegal for enslaved people.

But after a moment, he admitted:

“Yes, miss. I read what I can. Slowly, quietly. I taught myself.”

“What do you read?” she asked.

“Shakespeare,” he whispered.

She blinked.

“Shakespeare?”

“Yes, miss. The Tempest. Hamlet. Romeo and Juliet.”

He spoke with quiet reverence, as if the books were forbidden fruit.

“The Tempest is my favorite,” he said.

“Caliban is called a monster, but Shakespeare shows he is enslaved. His island stolen.

Prospero calls him savage—but Prospero is the invader.”

He paused.

“People think Caliban is the brute.

But maybe he’s more human than any of them.”

Elellanar’s breath caught.

She realized something profound:

Josiah was not a brute at all.

He was brilliant.

Compassionate.

Gentle.

And so she asked him the hardest questions:

“Are you dangerous?”

“No, miss.”

“Cruel?”

“No, miss.”

“Would you hurt me?”

His eyes softened.

“Never, miss.

Not you.

Not anyone who didn’t deserve it.”

She believed him.

And then she said the words that sealed both their fates:

“Call me Elellanar.”

V. The Ceremony That Wasn’t a Wedding

On April 1st, 1856, Colonel Whitmore gathered the household staff in a quiet room.

He read Bible verses.

Placed his daughter beside Josiah.

Declared the blacksmith responsible for her care.

And told the staff:

“He speaks with my authority regarding Elellanar’s welfare.”

Legally, it was not a wedding.

Socially, it was unthinkable.

But within the Whitmore estate, it became a covenant—one that would soon grow into something forbidden and beautiful.

VI. A Household Rearranged

Josiah’s new room was built beside Elellanar’s.

Separate, but connected by a private door.

He carried her when needed.

Helped her dress.

Maintained her dignity in intimate tasks no enslaved man had ever been permitted to perform for a white woman.

His gentleness astonished her.

She had expected awkwardness, discomfort, fear.

Instead, he moved with grace, reverence, and careful respect.

“Are you afraid of me?” he asked one morning.

“I was,” she admitted. “Not anymore.”

He looked relieved.

As if her acceptance mattered more than air.

VII. The Forge and the Fire

Elellanar wanted to try something no one had ever allowed her to do.

She wanted to forge iron.

Josiah hesitated—forge work was dangerous.

But at her insistence, he helped her.

He positioned her wheelchair near the anvil.

Handed her a smaller hammer.

Held the iron steady.

“Strike here,” he said. “Feel the metal move.”

She struck.

Weakly at first.

Then harder.

And harder.

When the metal cooled, Josiah handed her the bent piece.

“Your first creation,” he said.

“You’re stronger than you think.”

No one had ever told her that.

Not once in fourteen years.

VIII. The Quiet Bloom of Love

June brought a revelation neither could ignore.

Josiah was reading Keats aloud in the library.

His deep voice filled the room:

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever…”

They spoke of beauty, memory, life.

“What is the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen?” she asked.

He hesitated.

“You, at the forge yesterday,” he whispered.

“Covered in soot. Laughing. Alive.”

Her heart skipped.

And then she said words that could have destroyed them both:

“I think I’m falling in love with you.”

Dangerous words.

Criminal words.

Words that could get Josiah killed.

He tried to push her away gently.

“Ellanar… we can’t.”

“Why not?”

“It’s not safe. Not for you. Not for me.”

But she pressed forward.

“Do you feel the same?”

He broke.

“I’ve loved you since the day we spoke of Shakespeare,” he confessed.

“When you saw me—not the slave, not the brute.”

Their first kiss happened in the library—quiet, stolen, perfect.

But perfect does not last long in Virginia in 1856.

IX. Caught

On December 15th, 1856, they were discovered.

Her father walked into the library to find them kissing.

Josiah fell to his knees immediately.

“Sir, please,” he whispered. “This is my fault. Punish me, not her.”

But Elellanar refused to lie.

“I love him,” she said.

“And he loves me.”

It should have ended there—

with Josiah sold to the Deep South, tortured, or executed.

But something unexpected happened.

Her father did not scream.

He did not strike Josiah.

He did not threaten to separate them.

Instead, he ordered Josiah to his room…

and then asked Elellanar a simple question:

“Are you prepared for what your love will cost you?”

X. A Father’s Impossible Choice

For two months, Colonel Whitmore wrestled with an impossible dilemma.

If he kept Josiah enslaved, suspicion would eventually fall on the household.

If he sold Josiah, he would destroy his daughter.

If he allowed the relationship to continue in secret, someone would eventually discover it—and both would be ruined.

And so, in February 1857, he called them both to his study.

“I’ve made my decision,” he said.

They braced for the worst.

Instead, he said the one thing they never expected.

“Josiah, I’m freeing you.”

Elellanar gasped.

“And I’m sending you both North—with money, letters of introduction, and legal marriage papers. You will build a new life where no one knows you.”

Josiah wept.

Elellanar sobbed.

Their future—once impossible—became real.

But the cost was enormous.

Whitmore would lose his daughter, his reputation, and eventually, everything he had.

But he would save her happiness.

XI. The Journey to Freedom

On March 15th, 1857—exactly 38 years before Elellanar’s death—they left Virginia forever.

Their bags carried:

books

tools

clothing

Josiah’s freedom papers

They crossed into Pennsylvania without incident.

For the first time in his life, Josiah Freeman—he took the surname that day—walked as a free man.

Philadelphia became their refuge.

XII. Building a Life That Should Not Have Been Possible

With $50,000 from Elellanar’s father, Josiah opened Freeman’s Forge, a blacksmith shop that became one of the busiest in the city.

Elellanar managed the accounts.

Her education, dismissed in Virginia, became their greatest asset.

They had five children:

Thomas (1858) – later a physician

William (1860) – lawyer, civil rights advocate

Margaret (1863) – teacher

James (1865) – structural engineer

Elizabeth (1868) – writer

In 1865, Josiah built metal braces for Elellanar—ingenious devices that allowed her to stand and walk for the first time since childhood.

“You gave me everything,” she whispered.

“You already had everything,” he said.

“I only gave you tools.”

XIII. The Final Years

Colonel Whitmore visited twice.

He saw their home, grandchildren, business, life.

Before his death in 1870, he sent a final letter:

“Giving you to Josiah was the smartest decision I ever made.”

Elellanar died on March 15th, 1895—thirty-eight years to the day after leaving Virginia.

Josiah died the next morning.

The doctor said his heart simply stopped.

Their children knew better.

XIV. Legacy of an Impossible Love

Their shared headstone in Eden Cemetery reads:

Elellanar & Josiah Freeman

Married 1857 — Died 1895

Love That Defied Impossibility

In 1920, their daughter Elizabeth published a book titled:

My Mother, the Brute, and the Love That Changed Everything

It shocked the nation.

White society had tried to erase stories like this—interracial love, disability rights, emancipation through moral courage—but the Freeman family preserved every document:

freedom papers

marriage certificates

letters

business records

Colonel Whitmore’s handwritten confessions

Historians consider it one of the most remarkable love stories of the 19th century.

A disabled white woman and an enslaved black man—two people society dismissed—created a multigenerational legacy.

XV. What This Story Really Means

This is not simply a romance.

It is a story about:

disability

slavery

radical compassion

defiance against society

a father’s impossible love

a man misjudged by appearance

a woman underestimated all her life

freedom created through courage

Elellanar was not unmarriageable.

She was brilliant, powerful, resilient.

Josiah was not a brute.

He was poetic, gentle, extraordinary.

Together, they built a life that should never have been possible in 1856 America.

But it was.

Because one father saw what society refused to see:

His daughter’s worth—

and an enslaved man’s humanity.

Epilogue

If you are reading this, if their story moved you, then you are part of preserving a piece of history that was almost erased.

Elellanar and Josiah are gone.

But their story remains a reminder:

Love can break laws.

Love can defy centuries.

And sometimes, the most radical act a person can take…

is simply to see another human being clearly.

News

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO”

Steve Harvey STOPPED Family Feud When Mom Look at Son and Say THIS – Studio was SPEECHLESS | HO” It…

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He Kil.. | HO”

He Hired A HITMAN To Kill His Wife, Unknown To Him, The HITMAN Was Her Ex During College, & He…

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You | HO”

Her Husband Went To Work And NEVER Came Home – What She Found At His Funeral Will SHOCK You |…

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO”

Her Husband Bruised Her Face — The Next Morning, She Served Him A Breakfast He Never Expected… | HO” Her…

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO”

Climber Vanished in Colorado Mountains – 3 Months Later Drone Found Him Still Hanging on Cliff Edge | HO” A…

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO

My husband died years ago. Every month I sent his mom $200. But then… | HO Today was the fifth…

End of content

No more pages to load