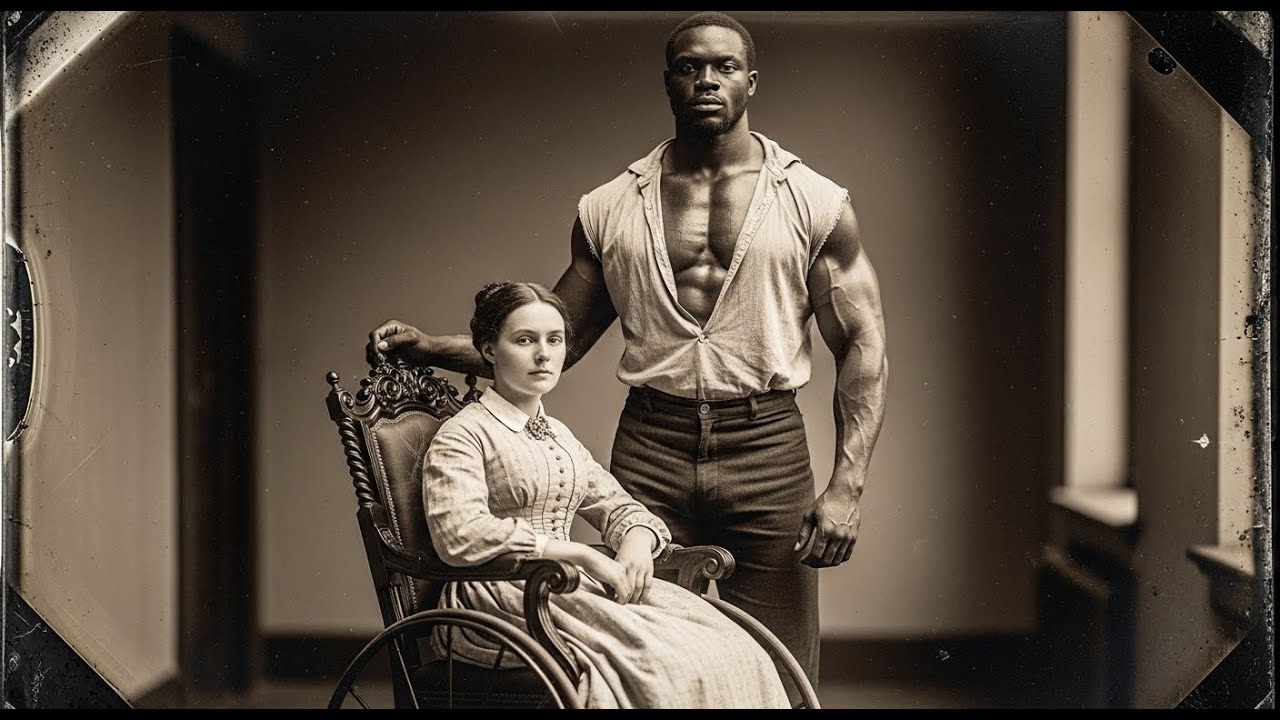

She Was Deemed Unmarriageable—So Her Father Gave Her to the Strongest Slave, Virginia 1856 | HO

In the archive room of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania sits a battered folio stamped FREEMAN PAPERS — 1857–1895. Inside are documents that, by all logic of their era, should not exist together:

Freedom papers for a 7-foot formerly enslaved blacksmith

A marriage record for a white woman from one of Virginia’s wealthiest slaveholding families

A ledger listing money transfers marked “for relocation & settlement”

Personal letters describing what one historian later called “the most improbable domestic arrangement in the antebellum South”

It is a story that, even by the standards of 19th-century scandal, stands alone. A story built on social collapse, legal impossibility, paternal desperation, and one young woman’s refusal to accept the role society assigned her.

The woman was Elellanar Whitmore, age 22, wheelchair-bound after a childhood accident.

The man was Josiah, known locally as “the brute,” an enslaved blacksmith whose extraordinary height and strength made him notorious throughout the region.

What happened between them in 1856 was not just a family affair.

It was, by every measure of the time, a legal impossibility — a crime in the eyes of Virginia law, a moral violation to Southern society, and a direct challenge to the slaveholding order.

This is the true-crime investigation into how a young disabled woman society dismissed as “unmarriageable,” and a man society reduced to “property,” navigated a labyrinth of legal danger and social taboo to escape the system designed to consume them both.

What makes this case extraordinary is not only what happened, but how it happened — and why the man who orchestrated it lost everything.

PART I — THE WOMAN SOCIETY DECLARED “DEFECTIVE”

A Childhood Accident, a Lifetime Sentence

Elellanar Whitmore was born into wealth. Her father, Colonel Richard Whitmore, owned more than 5,000 acres in Tidewater Virginia and over 200 enslaved people. By lineage and economic status, Eleanor (as some records spell her name) should have moved seamlessly into the ranks of the South’s planter-class wives.

But at age eight, a riding accident shattered her spine, leaving her legs permanently paralyzed.

Her survival was unusual. Her disability was unforgivable.

Southern ideals of womanhood — fertility, domestic management, social hosting — were not compatible with a daughter who required a wheelchair to move more than a few feet. In 1856, disability carried not only stigma, but legal and social consequences. It directly affected:

marriageability

inheritance rights

guardianship decisions

placement within extended family structures

Between 1852 and 1856, Colonel Whitmore attempted to arrange twelve separate matches for his daughter. Plantation society kept score. Every rejection added another layer of humiliation.

The recorded reasons were blunt:

“She cannot walk.”

“She cannot bear children.”

“She cannot manage a household.”

“She would be a burden in every respect.”

A local physician — who never examined her — publicly speculated that “spinal damage may impede reproduction.” The rumor spread quickly, and in an era obsessed with lineage, it became a social death sentence.

By February 1856, her reputation was ruined. She was spoken of in whispers. Planter wives pitied her. Young men avoided her.

The courts of the South saw disabled women as wards. The society around them saw them as burdens. In the eyes of the law, if her father died, her property and life decisions would fall to the nearest male relative — a cousin known for cruelty.

To Colonel Whitmore, this was the real threat.

And the fear of leaving his daughter defenseless set the stage for one of the most shocking paternal decisions documented in antebellum Virginia.

PART II — THE MAN THEY CALLED “THE BRUTE”

The Blacksmith With a Reputation

Plantation ledgers describe him simply:

“Josiah — male, height excessive, strength exceptional, trained in forging.”

Locals described him differently:

“A monster in the smithy.”

“Seven feet tall if he’s an inch.”

“Whitmore’s giant.”

He had been purchased at age 18 from an estate in Georgia. The transaction notes emphasize his physicality, not his temperament. By 1856, he was known throughout the county as the man who could:

bend horseshoes by hand

shoe eight horses in a day

carry broken farm machinery on his shoulders

But plantation rumor never saw the man, only the body.

Privately, however, Whitmore family notes reveal something else:

“The blacksmith reads in secret. Moderate skill. Prefers Shakespeare.”

To many planters, a literate enslaved man was more dangerous than a strong one.

Colonel Whitmore, however, saw something else:

an intelligent man capable of loyalty — if treated decently.

And most importantly: a man strong enough to defend his daughter once Whitmore himself was gone.

PART III — THE PROPOSAL THAT DEFIED EVERY SOUTHERN LAW

A Father’s Radical Decision

In March 1856, after the twelfth failed attempt to secure a husband for his daughter, Colonel Whitmore called her into his study. What he proposed was unprecedented, legally questionable, and socially catastrophic.

He told her, bluntly:

“No white man will marry you. But you need protection. When I die, your cousin will inherit everything.”

He then revealed his plan:

“I am giving you to Josiah.”

The phrasing, typical of the era, blurred disturbing lines.

But his meaning was clear:

He intended to create a domestic partnership between his daughter and the enslaved blacksmith — a relationship illegal in Virginia, unrecognized by law, but protected within his private domain.

To the colonel, it solved several problems:

His daughter would have a permanent protector.

A man bound to the estate would not abandon her.

Her cousin could not easily remove someone physically capable of defending her.

And beneath all of that — though never explicitly stated — was a more unsettling logic:

A disabled white woman deemed unmarriageable still needed a household guardian. In the twisted hierarchy of Southern law, that role could be filled by a man with no legal personhood at all.

The colonel’s reading of Virginia law was partially correct and partially naive. Enslaved men could indeed be placed as de facto guardians of white women within the confines of a plantation. But the moment such a bond became emotional, sexual, or public, it crossed into felony territory.

The colonel saw only necessity.

He did not foresee what would follow.

PART IV — THE ARRANGEMENT BEGINS

A Private Ceremony, a Public Secret

On April 1, 1856, Colonel Whitmore convened a small household gathering. He read from the Book of Ruth. He declared that Josiah would henceforth be responsible for the care, safety, and daily life of his daughter.

It was not a legal marriage — enslaved people could not enter contracts — but it was a formalized domestic bond.

Servants were told:

“He speaks with my authority in matters concerning Eleanor.”

The move was unprecedented enough that two staff members later recorded their shock in personal diaries. These diaries, preserved in archives, are crucial to reconstructing how the household perceived the event:

“Never seen the likes,” wrote Abigail Carter, a housemaid.

“Master gave the girl to the giant. Says he is to tend to her like a husband. It ain’t natural.”

For the first weeks, the arrangement was awkward but functional. Josiah handled:

transport between rooms

assistance with daily tasks

physical duties that maids could not manage

He remained subordinate in public, but privately occupied a role that defied every rule of slaveholding society.

What the colonel did not anticipate was the degree of intellectual compatibility between the two. The household staff recorded evenings spent reading Shakespeare aloud from Whitmore’s private library — a practice illegal for Josiah, but tolerated by the colonel.

Diaries note:

“Miss laughs more now than since the accident.”

But laughter was not the danger.

Attachment was.

And by December 1856, that attachment would explode into a full-fledged crisis.

PART V — DISCOVERY AND THE THREAT OF LEGAL RUIN

The Forbidden Becomes Visible

On December 15, 1856, Colonel Whitmore walked into the library and found his daughter and Josiah alone together in a moment of closeness later described only as “compromising” in family testimony.

The colonel’s reaction was immediate and severe. According to his surviving letter:

“I saw in their posture a familiarity that, if known beyond these walls, would destroy us all.”

Under Virginia law, several crimes could now be alleged:

Fornication between a white woman and a slave

Felonious conduct by an enslaved man toward a white woman

Moral corruption of a white woman

Harboring illegal interracial relations

The punishments ranged from public whipping to imprisonment — and for Josiah, execution.

By 1856, dozens of enslaved men had been lynched or legally executed for far less.

In that moment, the colonel faced a choice: punish the enslaved man, separate them, or conceal the truth.

What he chose shocked even his daughter.

PART VI — THE FATHER’S SECOND RADICAL DECISION

Freedom Papers and Exile

After two months of deliberation, consultations with lawyers, and private correspondence with abolitionist contacts in Philadelphia, Colonel Whitmore made a series of decisions that ruined his reputation and ended his standing in Virginia society.

He chose to:

Free Josiah through formal manumission

Legally marry his daughter and the formerly enslaved man in Richmond through a sympathetic minister

Provide $50,000 (nearly $1.7 million today) for them to start a new life in the North

Send them to Philadelphia with letters of introduction to abolitionist families

It was an extraordinary defiance of Southern law and custom.

Why did he do it?

Surviving correspondence provides clues:

“My daughter’s safety is worth more than the approval of men who do nothing for her.”

“I will not condemn her to a cousin’s mercy.”

“The law is wrong if it denies her a protector who has already proven loyal.”

Historians debate whether the colonel’s motivations were:

paternal

pragmatic

moral

or an act of quiet rebellion against the system he himself upheld

But the outcome was clear:

He had orchestrated one of the only documented cases of a white woman and a formerly enslaved man legally marrying before the Civil War.

And the price was catastrophic.

Whitmore’s will was contested, his reputation destroyed, and his family ostracized. Plantation neighbors shunned him. Some records suggest threats of vigilante retaliation.

By March 1857, the colonel insisted the couple flee immediately.

His final words to his daughter, preserved in a letter she kept all her life, read:

“I do not ask society’s permission to save you.”

PART VII — THE ESCAPE NORTH

Crossing State Lines Under Watch

Travel records show a hired carriage left Whitmore Plantation on March 15, 1857, carrying:

Eleanor Whitmore Freeman

Josiah Freeman

Two trunks of belongings

Manumission papers

Legal marriage documents

$50,000 in bonds

Their route avoided major towns and slave-catching patrols, traveling through Maryland and Delaware before reaching Pennsylvania, a free state.

Crossing into Philadelphia, the dynamic shifted instantly:

Josiah was no longer property.

Eleanor was no longer under Virginia guardianship.

Their marriage, invalid in the South, was recognized under Pennsylvania law.

They settled in a mixed-race neighborhood known for housing fugitives and free Black families. Within a year:

Josiah established Freeman’s Forge, quickly becoming a respected blacksmith.

Eleanor managed the books and handled business correspondence.

Financial and business records confirm rapid success. Local newspapers from the late 1850s mention:

“An exceptionally strong blacksmith newly arrived from Virginia… his shop known for excellent workmanship.”

Philadelphia census records document the births of their five children over the next decade.

PART VIII — THE FATHER WHO PAID THE PRICE

The Social and Financial Consequences

While Eleanor and Josiah rebuilt their lives, Colonel Whitmore’s world collapsed.

Court documents show that:

His extended family accused him of “moral corruption.”

Neighboring planters refused to trade with him.

His estate lost overseers and hired laborers.

His political offices were stripped.

More damning was the legal backlash. Manumitting a slave and facilitating a mixed-race marriage violated unspoken caste laws of the South more deeply than any statute.

A surviving letter from a neighboring plantation owner reads:

“Whitmore has disgraced his race. He will find no peace in this county again.”

By the time he died in 1870, he was isolated, his estate diminished, and his reputation permanently stained in Virginia society.

Yet his daughter’s life — the one he feared would be destroyed by disability and abandonment — flourished.

PART IX — A LIFE BUILT OUTSIDE THE SOUTH

Building Legacy in Philadelphia

Between 1857 and 1895, Eleanor and Josiah lived an entirely different life than the one the South imagined for them.

Their five children became:

a physician

a civil rights lawyer

a schoolteacher for Black children

an engineer

a writer

Their youngest, Elizabeth, published a book in 1920 recounting their family history. In it she wrote:

“My parents built a life from the ashes of two impossible worlds — one that rejected my mother, and one that owned my father.”

Their papers, donated to the Historical Society in 1965, remain one of the most complete archival records of a Southern interracial union before the Civil War.

PART X — THE TRUE CRIME OF THE SOUTH

The Crime Was Not Theirs — It Was the System

A true-crime investigation usually seeks:

a perpetrator

a victim

a motive

a consequence

In this case, the perpetrator was not a person, but a system.

The “crime,” as Virginia would have defined it, was the colonel’s deliberate sabotage of racial caste law.

The danger — the mortal danger — was borne entirely by Josiah.

Under Southern statutes, his mere proximity to a white woman placed him at risk of:

mutilation

lynching

execution

But the greatest crime of all was the one Southern society enacted against Eleanor:

the erasure of her autonomy

the labeling of her body as defective property

the refusal to allow her to inherit, marry freely, or even choose her own guardian

Colonel Whitmore’s actions may have been shocking, even ethically complicated, but they emerged from a system that offered him no humane alternatives.

In the end, he committed what the South saw as a crime:

He placed his daughter’s safety above the racial hierarchy that defined him.

And by doing so, he freed two people the system had condemned in different ways.

EPILOGUE — THE GRAVES AT EDEN CEMETERY

Eleanor died on March 15, 1895 — exactly 38 years after leaving Virginia. Josiah died the following day, March 16. Their children buried them together in Eden Cemetery, Philadelphia’s historic Black burial ground.

Their shared headstone reads:

“Ellanor & Josiah Freeman

Married 1857 — Died 1895

Love that defied impossibility.”

Their story is not a romance.

It is a crime story — a story of a society that tried to criminalize a woman’s disability, a man’s humanity, and a father’s attempt to protect his child.

Their lives illuminate the contradictions of a country that proclaimed liberty while enforcing bondage, that worshipped morality while criminalizing compassion, and that punished the breaking of unjust rules more harshly than cruelty itself.

In 1856, everything about their union was illegal.

In 2025, everything about it is history.

But the investigative trail they left behind — the papers, the letters, the court challenges, the testimonies — forces us to confront a question the South never allowed:

What was truly criminal — the love and protection these two people found, or the laws that forbade it?

Their archive does not answer the question.

It simply preserves the evidence.

And sometimes, in true crime, evidence speaks louder than verdicts.

News

6 Hours After The BURIAL of His Wife, He Was Seen In A NIGHTCLUB | HO

The marriage became transactional without anyone signing a contract. Kira worked harder to cover mounting expenses while Terrell treated her…

Married Cop 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐭𝐬 Her Ex 8 Times After He Refuses $*𝐱 With Her | HO

Married Cop 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐭𝐬 Her Ex 8 Times After He Refuses $*𝐱 With Her | HO Lambert’s fresh start didn’t begin…

ICE Agent Tries to Play the Victim, Local Police Were NOT Having It | HO

“So what’s going on?” an officer asks him. “So I found him. I think he’s a federal agent,” the man…

Garbage Workers Hear Noise Inside a Trash Bag, He Turns Pale When He Sees What It Is | HO!!

Garbage Workers Hear Noise Inside a Trash Bag, He Turns Pale When He Sees What It Is | HO!! The…

The Appalachian Revenge K!lling: The Harlow Clan Who Hunted 10 Lawmen After the Still Raid | HO!!

The Appalachian Revenge K!lling: The Harlow Clan Who Hunted 10 Lawmen After the Still Raid | HO!! The motive wasn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load