Solomon’s Revenge: The Charleston Slave Who ʙᴜʀɪᴇᴅ 9 Masters Alive | HO

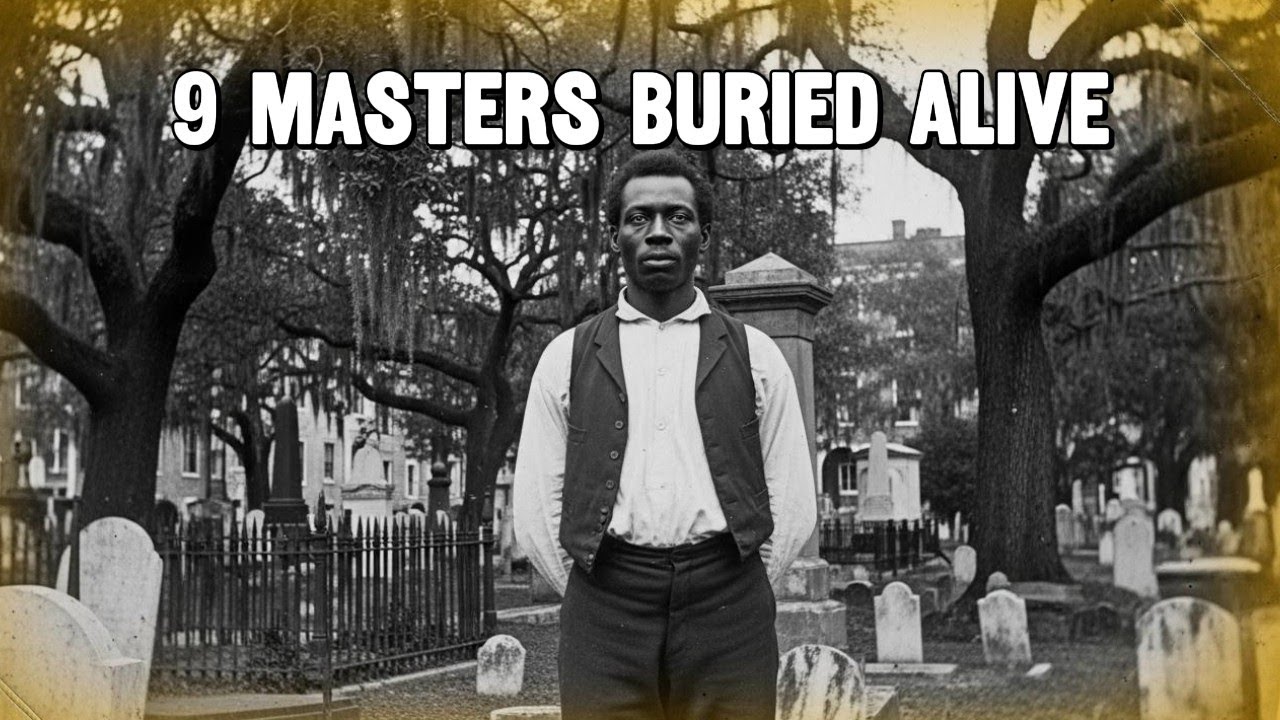

Beneath the moss-draped oaks of St. Michael’s Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina, lies a row of nine headstones that for generations, no one dared to discuss. Each stone bears the name of a plantation owner — men of wealth, status, and power — all dead between 1851 and 1855.

Their official cause of death? “Sudden paralysis followed by merciful passing.”

But when cemetery renovations took place in 1923, the workers uncovered a secret that the city immediately sealed from public record. The coffins of those nine men told a different story.

Each lid was shredded with fingernail marks, and the corpses inside were twisted in positions of desperate struggle. They had not died peacefully. They had been buried alive.

Buried alongside them, beneath the cemetery’s oldest magnolia tree, was a leather-bound journal — the confession of a man named Solomon Fairfax, a former slave and physician’s assistant who had turned his medical knowledge into the most calculated revenge Charleston had ever seen.

His first line set the tone for everything that followed:

“Today I watched my wife and children burn, and I did nothing to stop it.”

It was the beginning of a nightmare Charleston’s elite would spend the next century trying to erase.

The Healer Turned Hunter

In the glittering years before the Civil War, Charleston was the pride of the South — white-columned mansions, lavish plantations, and fortunes built on human suffering. Among the city’s most respected men was Dr. Cornelius Hatheraway, a physician known for his “modern” medical methods and his prized assistant — a slave named Solomon Fairfax.

Solomon was no ordinary servant. Educated, literate, and trained in both European and African medicinal traditions, he was the mind behind many of Hatheraway’s miraculous “cures.” His hands saved countless lives, white and Black alike.

But his own life had been torn apart.

Before working for Dr. Hatheraway, Solomon had lived on the Pemberton plantation with his wife Celia and their three children. When the plantation’s owner, Edmund Pemberton, fell into debt, he sold Solomon’s family to pay his creditors.

Solomon begged to buy their freedom with his labor. Pemberton refused.

During the journey to Charleston’s slave market, Celia fell from the wagon and suffered a fatal head wound. The traders left her in the road to die.

At the auction, Solomon watched his children sold to different buyers. His eldest son went to a rice plantation near Georgetown; his youngest daughter, Grace, was purchased as a house servant in Savannah. He never saw them again.

That night, under the flickering light of a candle in his new quarters above Dr. Hatheraway’s office, Solomon opened his journal. His trembling hand wrote words that would define the rest of his life:

“They think they’ve broken me. But they have only taught me patience.”

A Study in Death

For months, Solomon worked as though nothing had changed. He mixed compounds, tended to Charleston’s wealthiest patients, and listened carefully.

Through whispers in the grand houses, he identified nine men responsible for his family’s destruction — planters, financiers, and slave traders who had profited from the same auction that shattered his life.

He recorded their names in his journal like case notes:

“Nine afflictions. Nine cures. All of them deserve the same medicine.”

In Dr. Hatheraway’s library, Solomon discovered something extraordinary — a medical text describing a South American vine toxin capable of inducing total paralysis while leaving the mind conscious. It was meant for experimental surgery. In Solomon’s hands, it became a weapon.

He learned to extract and refine the toxin, testing it carefully on lab mice. Too much caused instant death. Too little caused temporary weakness. But the right dose left the body frozen, the lungs barely moving, the pulse nearly undetectable — a state that mimicked death perfectly.

And the worst part? The victim remained fully aware.

Solomon wrote in his journal:

“They will not die quickly. They will die knowing.”

The First Burial

His first target was Colonel Reginald Fitzpatrick, a rice baron who had once joked about the “breeding value” of Solomon’s children.

On December 15, 1852, Fitzpatrick came to Dr. Hatheraway’s office complaining of gout. The doctor was busy, leaving Solomon to administer treatment. Into the colonel’s tonic, Solomon added three drops of the toxin.

Minutes later, Fitzpatrick felt weak.

“Strange… can’t move…”

Solomon leaned close. “You remember me,” he whispered. “You laughed when they sold my sons. Now you will learn what that laughter cost.”

The paralysis set in. Fitzpatrick’s eyes darted wildly, his mouth frozen open, his body rigid.

“You are not dead yet,” Solomon said softly. “Dr. Hatheraway will declare you gone, and by this time tomorrow, you will be under the earth — alive.”

When the doctor returned, he found his patient apparently lifeless. Heart failure, he concluded. Natural causes.

The next afternoon, Colonel Fitzpatrick was buried with full honors at St. Michael’s Cemetery. Solomon watched from the segregated section as the first shovel of dirt struck the coffin. He wondered how long the colonel’s awareness lasted.

That night, Solomon wrote:

“One is judged. Eight remain.”

The Pattern of Death

Over the next year, Charleston’s upper class whispered about a strange wave of sudden fatalities. Judges, planters, and ship owners collapsed from mysterious strokes and heart failures.

Among them was Judge Marcus Calverton, who had defended the legality of separating enslaved families. His body, too, bore signs of “unusual stiffness.” No one questioned it.

But one man did — Thomas Grimby, a journalist for The Charleston Mercury. He began documenting these “prominent deaths,” noticing that all shared one connection: treatment by Dr. Hatheraway’s practice.

Solomon knew time was running out. A new assistant, Dr. Timothy Henderson, had joined the office — young, curious, and well-trained in forensic medicine. If Solomon waited much longer, his methods would be discovered.

He decided to act fast. Too fast.

His next victim, Captain William Dandridge, a ship owner who trafficked enslaved people, died suddenly during a dinner party after eating dessert laced with Solomon’s toxin. Unlike the others, Dandridge died in front of witnesses.

The word poison spread through Charleston like fire.

Grimby was the first reporter at the scene. When he learned Solomon had served that dinner, the puzzle pieces began to fit.

The Final Night

Knowing he would soon be exposed, Solomon planned one last act — a mass execution.

On June 15, 1853, six of Charleston’s wealthiest slave traders met at the offices of Henderson & Associates. Solomon, using his access to medical supplies, infused the building’s gas lamps with a concentrated form of the toxin.

When the men lit the lamps, the air itself became poison.

Within thirty minutes, the room fell silent.

When Solomon entered, the six men sat frozen around the conference table — eyes wide, bodies still, trapped inside their own paralyzed flesh.

He walked among them, whispering each of their names.

“You will not scream. You will not run. You will die remembering the faces of the people you destroyed.”

But then came footsteps. The door opened.

Thomas Grimby stood there, notebook in hand, staring at the horror before him.

“My God,” he breathed. “It’s true.”

Solomon did not deny it. “They buried my wife. They sold my children. I only returned what they gave.”

Moments later, city constables burst into the building. They found Solomon standing calmly among the paralyzed men. He surrendered without a word.

The Trial That Shook Charleston

The trial of Solomon Fairfax began that fall and drew crowds from across the South. His confession was meticulous, written in the same careful hand that had once recorded patient doses.

Charleston’s prosecutor called him a monster. His court-appointed lawyer called him a man driven past the limits of human endurance.

For the first time, the city heard in open court the full cruelty of the slave trade — the family separations, the auctions, the “losses” written off as accounting entries. Solomon’s testimony forced Charleston’s society to confront what it had always denied: that slavery was not benevolent, but barbaric.

Even the survivors of Solomon’s toxin — men who had awakened in their own coffins — struggled to speak of him without fear or awe. One of them, Colonel Harrison Vance, told the court:

“I heard my wife weeping over my body. I could not move, could not speak. I was buried alive inside myself. He gave me terror beyond comprehension. But he also gave me understanding.”

The jury deliberated less than an hour.

On October 15, 1853, Solomon Fairfax was hanged before a crowd of two thousand. His final words, recorded by journalist Thomas Grimby, still echo across Charleston’s history:

“Nine men felt the terror my children felt. I die content. But this system will breed more men like me. Even patience has limits.”

The Journal Beneath the Magnolia

Solomon was buried in an unmarked grave. His journal, entered into evidence during the trial, vanished from public record.

Years later, Grimby — haunted by the story — confessed in his private papers that he had copied and hidden the original journal beneath the magnolia tree in St. Michael’s Cemetery, near the graves of Solomon’s victims.

“I could not destroy his words,” Grimby wrote. “Perhaps future generations will read them with understanding rather than fear.”

When the journal was unearthed in 1923, along with the nine coffins scarred by fingernails, Charleston’s officials sealed the files, citing “concerns about public unrest.”

But the truth could not stay buried forever.

The Legacy of a Dark Genius

Solomon’s revenge rippled far beyond Charleston. Across the antebellum South, slave owners began to fear their most educated slaves — especially those trained in medicine. Laws were passed forbidding enslaved people from learning chemistry or pharmacology.

Ironically, Solomon’s actions also advanced the field of forensic science. His use of undetectable toxins inspired new research into post-mortem chemical analysis — the beginnings of modern toxicology.

Yet the deeper legacy was moral. For decades, Southern families whispered his name like a curse. To others, especially the descendants of the enslaved, Solomon Fairfax became a legend — not of evil, but of defiance.

He was the healer who learned to kill, the man who forced a city to face its sins through the same medicine it prescribed to others.

A Warning From the Grave

Today, if you visit St. Michael’s Cemetery, you’ll find the nine graves still standing in their quiet row — names carved in marble, stories carved in silence.

Local guides rarely mention them. The city’s records list only “renovation anomalies.”

But beneath the magnolia tree, where the soil was disturbed a century ago, visitors sometimes leave small offerings — flowers, candles, handwritten notes.

One note, left anonymously last year, reads:

“Justice delayed is not justice denied. It just waits for someone brave enough to dig it up.”

And perhaps that is Solomon Fairfax’s final lesson.

That the past never truly stays buried. It only waits — patient, silent, and alive.

News

1 MINUTE AGO: Rob Reiner’s Daughter Tracy Speaks Out After Her Parents’ Deaths | HO!!

1 MINUTE AGO: Rob Reiner’s Daughter Tracy Speaks Out After Her Parents’ Deaths | HO!! For decades, the Brentwood home…

After Decades, Soon Yi – Previn Finally Admits the Truth About Her Marriage to Woody Allen | HO!!

After Decades, Soon Yi – Previn Finally Admits the Truth About Her Marriage to Woody Allen | HO!! For more…

Dean Martin STOPPED Mid-Song When He Saw An Old Man Being Dragged Out By Security. | HO!!

Dean Martin STOPPED Mid-Song When He Saw An Old Man Being Dragged Out By Security. | HO!! Dean Martin was…

At Age 54, Rozonda ‘Chilli’ Thomas FINALLY Reveals Her TRAGIC Story! | HO!!

At Age 54, Rozonda ‘Chilli’ Thomas FINALLY Reveals Her TRAGIC Story! | HO!! For decades, she was America’s dream girl….

A Mafia Boss Humiliated Dean Martin in Public — His Response Changed Hollywood | HO!!

A Mafia Boss Humiliated Dean Martin in Public — His Response Changed Hollywood | HO!! Las Vegas, February 12, 1962,…

MOTHER Watches As Husband & Son ᴀʙᴜsᴇᴅ Her Disabled Daughter For 2 Years, Got Her Pregnant & Brutal | HO!!!!

MOTHER Watches As Husband & Son ᴀʙᴜsᴇᴅ Her Disabled Daughter For 2 Years, Got Her Pregnant & Brutal | HO!!!!…

End of content

No more pages to load