Teen Girl Disappeared in 1987 — 7 Years Later, a Construction Crew Found Her Lost Backpack | HO

On a faded notice board inside the Knoxville Police Department, between a photocopied “Neighborhood Watch” flyer and a curling sheet with a US flag printed in the corner, a single page had been thumbtacked up for years. “MISSING JUVENILE – CHENISE PORTER, AGE 15.” The ink had gone soft at the edges; the photo looked like it belonged to another era—big glasses, high‑waisted jeans, a shy half‑smile.

Newer cases layered over it, but nobody took it down. In 1987 she’d walked out of a small house and vanished, leaving behind her sneakers, her light jacket, and a mother who refused to believe her daughter had simply chosen to disappear.

Seven years later, on a hot June afternoon, a construction worker’s shovel would hit something hard out on the edge of the city. A little metal letter. A locker key. Things that should have been in a teenager’s backpack, not buried under three feet of red clay and fill.

In the spring of 1987, Knoxville, Tennessee moved at its usual pace—school buses, factory whistles, cassette tapes in car stereos. Fifteen‑year‑old Chenise Porter’s days followed that rhythm. She went to school, turned in her homework, sat with the same two friends at lunch. Sometimes she stayed after for a club meeting or to cut through the gym and watch boys shoot hoops.

At home, life was tighter.

She lived with her mother, Lydia, and her stepfather, Marlon Doyle, in a modest single‑story house. Marlon worked as a heavy equipment operator on a construction site out past the city limits, the kind of job that left his boots caked in Tennessee clay and his shoulders tight by the time he walked in the door.

Neighbors said the house had grown louder over the last year. Thuds of doors. Raised voices. Conversations that started low and ended with somebody stomping down the hallway.

“Everything okay over there?” one neighbor had asked Lydia once on a Saturday morning, leaning over the chain‑link fence.

“We’re fine,” Lydia had said, forcing a smile. “You know teenagers.”

She hadn’t said that the arguments weren’t just over curfews or report cards.

Hinged sentence: From the outside, the Porter house still looked like any other small Knoxville home with a flag stuck in a flowerpot and a swing on the porch—but inside, the air had started to hold its breath.

The night things stopped following their usual script, Lydia was working a late shift. She checked the clock above the break room microwave as she rinsed out her coffee mug: 10:15 p.m. Her feet ached. She pictured her daughter on the couch, probably half asleep with the TV on.

She pulled into the driveway a little before eleven. The porch light was on, but the front door was unlocked, which needled her. She stepped inside.

The house was dark. Quiet, but not the comfortable kind. Just… still.

“Chenise?” she called.

No answer.

In the kitchen, the counter was bare. No dishes in the sink, no crumbs, no half‑eaten sandwich. The trash can lid was closed. The air smelled like nothing.

She moved down the hallway. In the small bedroom at the end, Chenise’s sneakers sat neatly by the dresser. Her light jacket was draped over the back of a chair. School notebooks were stacked on the desk; her pencil case lay open, a pen uncapped as if she’d set it down mid‑sentence.

There were no overturned chairs, no broken glass, no handwritten note on the bed. Just the complete absence of a fifteen‑year‑old girl from a room that still held the shape of her day.

Lydia checked the bathroom, then the tiny laundry room. Nothing. The back door was shut and locked.

She picked up the jacket, then set it back down. If her daughter had gone somewhere, she would have taken it. Nights could still turn cool in April.

She went back outside, scanning the dark street. A dog barked three houses down. Somewhere a TV glowed blue behind curtains.

She waited in the kitchen, one hand on the phone. The clock on the stove flipped to 11:20.

At 11:30, the front door opened. Marlon stepped in, pulling off his work jacket. The bright overhead light caught the fabric: heavy brown canvas stained dark with wet, red clay. Not the dry dust that clung to clothes at the end of a shift, but thick, fresh mud, smeared across the sleeves and shoulders.

“Where have you been?” Lydia asked.

“Got called out to the site,” he said. “They were having trouble with a loader. I told you they been breaking down.”

“Have you seen Chenise?” she asked. “She’s not here. Her shoes are here. Her jacket is here.”

“She’s probably out,” he said, shrugging. “You know how kids are. She’ll come back when she cools off.”

“She didn’t take her jacket,” Lydia said.

He shrugged again, hanging the muddy jacket over a chair. “I’m beat, Lyd. Been out in that clay all night.”

“I’m calling her friends,” Lydia said, already reaching for the phone.

Marlon didn’t volunteer to help. He opened the fridge, grabbed a beer, and sat at the table, his jaw tight.

One by one, the closest friends answered groggy or confused. “No, ma’am, we haven’t seen her since school.” “No, she’s not here.” “If she comes by, I’ll tell her to call you.”

After the calls, Lydia grabbed a flashlight.

“I’m going to look,” she said.

“At this hour?” Marlon asked. “What you gonna see in the dark?”

“I’m not just sitting here,” she snapped.

She walked the neighborhood. The small park two blocks away, its swings creaking in the night breeze. The corner store with the flickering neon OPEN sign. The route kids used to cut home from school. She called her daughter’s name more quietly now, not wanting to wake anyone.

No signs. No girl hunched at a bus stop. No groups of teens on the sidewalk.

Back at the house, Marlon was in the living room, TV on low. He didn’t stand when she came in.

“Nothing,” she said.

“She’ll turn up,” he repeated. “You’ll see.”

The next morning, with sunlight showing every corner of the empty bedroom as clearly as the night before had hidden it, Lydia dialed the police.

Hinged sentence: When Lydia called 911 that morning, she wasn’t reporting a runaway; she was reporting a silence that didn’t fit anything she knew about her child.

Officers arrived and followed the standard missing‑person protocol for a minor. They took a recent photo. They asked about friends, habits, arguments. They walked the small yard, checked behind the shed, scanned the drainage ditch that ran behind the houses.

There were no scuff marks, no trampled bushes, no sign anyone had forced their way in or out.

They took statements from the neighbors.

“Did you hear anything unusual yesterday?”

“One of those afternoons,” a woman from across the street said. “Heard shouting. Sounded like her and him at the front door. It got pretty heated, then the door slammed. After that, nothing.”

Another neighbor echoed that: voices raised, but no words distinguishable. Just the sharpness.

Officers noted it down. They brought Marlon in for more questions.

He stuck to his version. Argument in the afternoon, yes. He couldn’t even remember what it was about. “Teenage stuff,” he said. He claimed he left for the bar later, had one beer, then got “called out” to the construction site to check a piece of machinery. No, there were no logs for that; the company trusted him with a key. No, he hadn’t seen or heard from Chenise since before the argument.

His employer confirmed one thing: yes, Marlon had keys. Yes, it was normal for him to swing by after hours to check on equipment.

The house was examined again. The pickup truck’s bed and cab were looked over. The truck was dusty, scratched, and carried the usual cargo of a workman’s life—tools, straps, an old coffee thermos. Nothing stood out as immediately alarming.

In the kitchen, while officers walked through, Lydia mentioned something that tugged at her.

“There was a big roll of tarp in the garage,” she said. “Heavy one. He uses it when he hauls stuff. I can’t find it.”

“We’ll make a note of it,” one officer said, jotting it down. It was logged under “miscellaneous,” just one more detail in a growing file.

Search efforts spread out in the following days. Law enforcement, volunteers, and community groups walked wooded areas, checked embankments, drainage ditches, and roadside brush. Flyers with her school photo went up in grocery stores, laundromats, church bulletin boards.

No one came forward with a sighting. No bus drivers remembered picking up a girl matching her description. No airline, bus terminal, or train station had records involving her name.

Investigators tried to get into the construction site where Marlon worked, but the landscape was a maze. Huge mounds of red clay, fill dirt, broken concrete. Bulldozers rolled through daily, moving earth from one side to another.

“Unless you can tell me the exact square foot you want,” the site manager had said back then, “we’d be digging blind.”

There were no cameras, no check‑in sheets. Dirt came in on trucks and left on trucks. The ground was a living thing, constantly reshaped.

Weeks bled into months. Leads dried up. The notes in the file shifted from “active” to “no new information.” Lydia’s questions didn’t.

At home, she went through her daughter’s room again and again. Letters, doodles in the margins of notebooks, the backs of Polaroids. Nothing hinted at secret plans or a hidden boyfriend in another state. There were no travel brochures, no talk of running away.

Her conversations with Marlon grew shorter. She watched his face when he said, “She’ll come back.” Something in her recoiled.

She filed for divorce before the year was out. When she left the house, she took a small number of things—a box of photos, a few clothes, important papers. Before she walked out, she grabbed one more item from the back of a chair.

Marlon’s work jacket. The one that had been thick with clay that first night.

She folded it and put it with her belongings, without telling him.

Hinged sentence: On paper, the case file now read like so many others—a minor left home and did not return—but in a cardboard box under a bed at Lydia’s sister’s house, a stained jacket sat like a stubborn question.

Seven years changed Knoxville’s edges. Vacant lots turned into warehouses and shopping centers. Old industrial patches were scraped flat and covered in asphalt, fences, and sodium‑vapor lights.

The construction site where Marlon had once moved earth with a bulldozer no longer looked like a raw set of mounds. By 1994, a small warehouse complex stood on most of that land—dock doors, painted stripes on smooth blacktop, new drainage systems.

But one corner never got pulled into the blueprint. A sliver of ground at the edge, too awkwardly shaped or too easily overlooked, stayed wild. Tall grass, saplings, a tangle of brush, and old bits of construction trash—pieces of wood, rusted wire.

In early summer, a utility crew got an order: clear that leftover strip and prep it to run underground cable. Nothing fancy. Bring the brush cutter, a small bulldozer, shovels, trenching tools. Get the job done before the end of the week.

The sun beat down as they sliced through years of growth. Roots crunched under the machines, and the dry top layer of soil turned to dust.

One worker, James, was using a shovel to break up a stubborn clump of dirt at the edge of a shallow rut. The soil there was weird—patchy, layers of red and darker fill, pebbles and chunks of old brick mixed in.

His shovel hit something that didn’t sound like rock. A sharp, small scrape.

He crouched down and brushed with his gloved hand. Something metallic winked back at him in the dirt—a tiny letter charm on a busted chain, worn dull along the edges. A few inches away, almost swallowed by mud, was a small locker key on a thin tag stamped with a number.

“Hey,” James called to the foreman. “Got something.”

The company had a simple rule hammered in by lawyers: if you find anything that looks like personal property on a job, you bag it and report it. Especially on old industrial land. Nobody wanted to be the crew that tossed something important.

The foreman pulled a clear plastic bag from the truck, held it open while James dropped the items in. A little charm. A key that looked like it belonged on a school locker, not a front door.

They finished the trench. At the end of the shift, the foreman drove the evidence bag down to the police station.

At the station, the items were logged, then handed to a detective. The key’s tag number was clear. A quick call went out to the school district records office.

“Locker number?” the clerk asked. “Hold on.”

It took less than 10 minutes.

“That key was assigned to a student named Chenise Porter,” the clerk said. “Missing since 1987.”

In the conference room, the detective compared the little metal charm to an old list of her personal effects that had been compiled back then. There it was: “silver‑colored letter C charm on backpack zipper.”

They called Lydia.

She sat across from them, hands twisting in her lap, as an officer slid the small bag across the table.

“Ms. Porter,” he said gently. “Do you recognize this?”

The charm looked smaller now than it had against her daughter’s backpack. Lydia’s throat tightened.

“I bought that at a shop near the school,” she said. “C for Chenise. She put it on her bag. She never took it off.”

She didn’t need to hold it. One look was enough.

Hinged sentence: For Lydia, the key and the tiny letter didn’t so much give her new information as they finally gave the department something she’d lived with alone for seven years—a physical acknowledgment that her daughter hadn’t just walked away.

The significance of the find wasn’t in the objects themselves so much as where they’d been buried.

Chenise had no reason to be on that patch of ground. She hadn’t hung around industrial lots or taken shortcuts through raw construction fields. She didn’t drive. The undeveloped strip sat on the outskirts, not on the way to anywhere in her life.

If her locker key and backpack charm were there, someone else had brought them.

The old case file came back out of storage. The thick paper smelled faintly of dust and toner. The notes about neighbor statements. The mention of Marlon’s red clay‑stained jacket. The missing roll of heavy tarp in the garage. The reference to his work at a then‑active construction site.

Investigators noted that in 1987, they’d tried to look at that construction property. But back then it had been a constantly shifting landscape. Earth moved daily. Piles that were there one week got flattened the next. Nothing stayed put long enough for a systematic search to hold.

The 1994 discovery changed that calculus. The portion of land where James had found the key and charm sat in an area that, according to city engineering maps, had been built up using fill from earlier construction work. In other words: dirt and debris from the original site had been moved there and left.

What had once been a top layer in 1987 might now be three feet down or ten yards to the left.

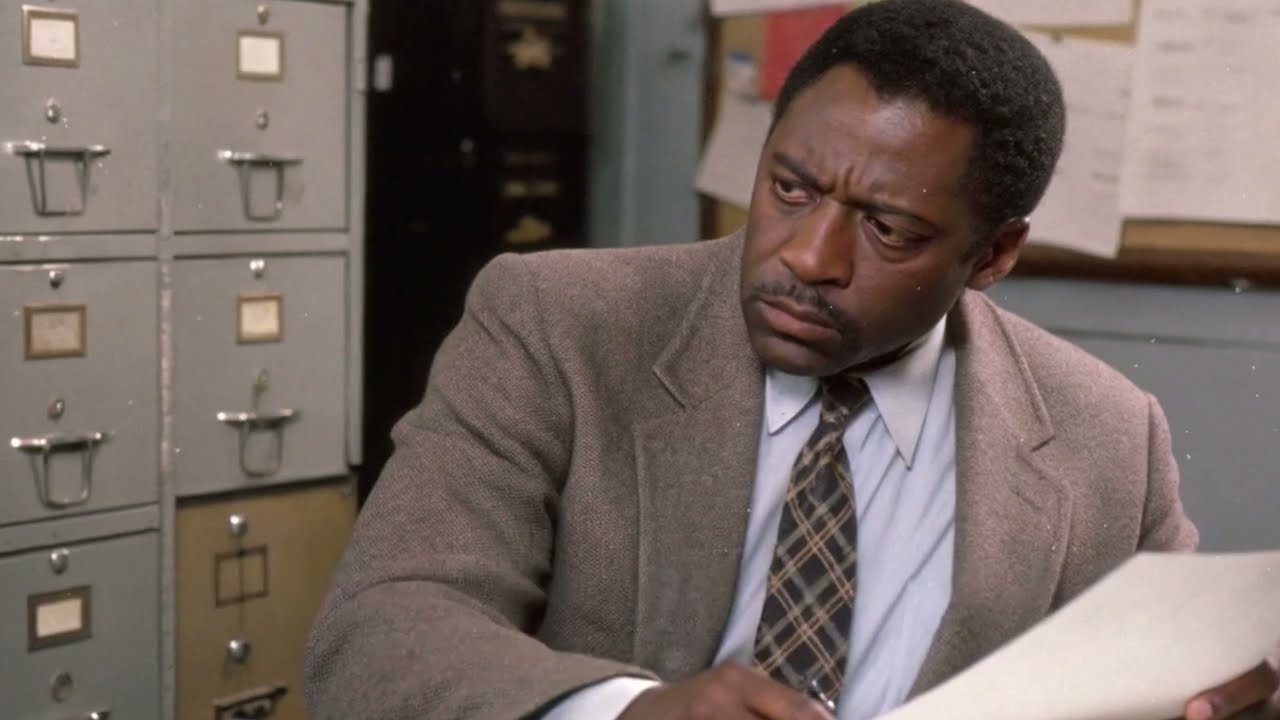

The missing persons case was reclassified as an active investigation again. A new detective, Leon Crowell, was assigned.

Crowell wasn’t interested in coming up with brilliant new theories. He started at the beginning.

He read every page from 1987—home inspection notes, neighbor interviews, that small line about the missing tarp. He studied the map showing the old construction site boundaries overlaid on the new warehouse.

He circled one name: Marlon Doyle.

Buried in the old file was a mention that hadn’t carried much weight before: several years prior to Chenise’s disappearance, Marlon had been convicted in connection with a physical altercation. He’d served his sentence, completed probation.

Back then, it hadn’t been considered relevant. There had been no clear link between that past and the missing teen. Now, as a behavioral flag, Crowell marked it. Not proof, but context. Evidence that under stress, Marlon had a record of letting his temper break the surface.

Two details on the old pages now felt heavier: the jacket with thick, fresh red clay on it the night she vanished, and the missing heavy tarp Lydia had noticed.

Those two items now connected directly to a physical location: a construction site whose dirt had ended up under that untouched strip where the crew had been digging.

Crowell initiated an evidence inventory. He wanted to know if anything from 1987 had survived.

Lydia came in carrying a worn cardboard box. Inside, wrapped in an old sheet, was Marlon’s work jacket.

“I took it when I left,” she explained. “He never noticed. I knew… I knew something about that night wasn’t right. I couldn’t say why. Just… that clay wasn’t like the usual. It was different. Thicker. Newer.”

The jacket was sent to the lab.

For forensic analysts, soil isn’t just dirt. It’s a fingerprint—in the right hands.

They scraped tiny samples from the embedded clay, then compared its mineral content, grain size, and oxide pattern to soil cores pulled from the construction area where the key and charm had surfaced.

The report came back with clear language: full compositional match. Not “similar to other red clay in Knox County,” but “consistent with the specific site where the items were recovered.”

While the jacket was being analyzed, Crowell went back into the neighborhood timeline. Neighbors had heard an argument late afternoon, voices raised, door slam. Lydia’s work schedule showed she was still at her job at that time.

The file also contained a brief mention of a bar within walking distance of the Porter house. Marlon had been known to stop there occasionally. In 1987, that detail hadn’t been chased down. Now, it mattered.

Crowell walked into the bar, which still smelled like spilled beer and fryer oil eight years later. A different jukebox, same worn stools.

“I’m looking for anyone who was a regular here back in the late ’80s,” he told the bartender.

“Most of us are still here,” came a voice from a corner stool. “Depending on your definition of ‘regular.’”

The man introduced himself as Barney Harrell. His name popped in Crowell’s notes from the old case as someone who’d vaguely mentioned seeing Marlon once.

Crowell asked him to come down to the station.

There, under a recorder’s red light, Barney recounted the night Marlon came in.

“He looked like he had a storm cloud over him,” Barney said. “Came in alone. Ordered the cheapest thing on tap. Drank it like medicine, not like he was enjoying it.”

“Did he say anything?” Crowell asked.

“Grumbled about home,” Barney said. “Said that girl—Chenise—didn’t show him any respect. That things were getting out of hand. I thought it was just more grown‑up griping about teenagers. He wasn’t covered in mud or anything. Clothes looked clean. Not like he’d been crawling around in clay.”

“How long did he stay?” Crowell pressed.

“Ten, fifteen minutes, tops,” Barney said. “He wasn’t there to hang out. Just to get his head straight, I guess. Then he left.”

That put Marlon at the bar after the argument, before the jacket got caked in clay.

Now Crowell had three solid time points: the afternoon argument, the brief stop at the bar, and Marlon’s 11:30 p.m. return home wearing that clay‑stained jacket.

In between the bar and the house? A gap.

The lab report closed part of it. The clay on the jacket came from the construction site whose soil had eventually swallowed and then spit out pieces of a teenager’s backpack.

Hinged sentence: What had once looked like scattered trivia—an argument here, a bar visit there, a missing tarp, a dirty jacket—had started lining up like coordinates, all pointing toward the same patch of churned‑up ground on the edge of Knoxville.

Crowell requested old records from the construction company that had employed Marlon. They dug out what they had: lists of who had keys, guidelines for equipment operators, memos about after‑hours maintenance.

Marlon was on the short list of workers with master keys. His job involved making sure machinery was operational, sometimes outside regular shifts. There were no time logs. No cameras. No gate guard.

Former coworker Derek Collins confirmed it.

“If something broke down,” Derek explained, “Marlon was one of the guys they called. He could roll in at midnight, fix a blown hose, check a bulldozer. Nobody blinked. We didn’t sign in or out. It was loose.”

Derek didn’t speculate about that specific night. He didn’t have to. His statement simply confirmed: if Marlon had wanted to be on site late, nobody would have questioned it. He had the keys and the cover of his job.

With soil science, access records, and neighbor and bar testimony aligned, Crowell moved to the next step: bring Marlon in.

The interview room was standard—table bolted to the floor, two chairs, small camera in the corner.

“You understand your rights?” Crowell asked.

Marlon nodded. His hair was more gray now, his face lined. He still wore the same kind of work boots.

“I’ve told this story before,” Marlon said. “Back then. Didn’t nobody believe me then either.”

“Tell it again,” Crowell said. “From the afternoon.”

Marlon admitted to an argument. “She mouthed off,” he said. “I told her to do something; she rolled her eyes. You know how teenagers are.”

“What happened after the argument?” Crowell asked.

“I left,” Marlon said. “Went to Riverside, had a drink. Then I got called out to the site. Checked on some equipment.”

“Which piece?” Crowell asked. “You remember?”

“It was years ago,” Marlon said. “How I’m supposed to remember details like that?”

“Your jacket was covered in fresh clay when you came home,” Crowell said. “Not dust from earlier that day. Wet clay. We tested it. It matches the soil from the exact area where parts of Chenise’s backpack were found.”

Marlon’s jaw tensed. “I worked that site all the time,” he said. “Of course my clothes had clay on them.”

“This isn’t general,” Crowell said. “It’s specific. Same mix, same trace minerals. Same spot.”

Marlon shrugged. “You can make dirt say anything you want on paper.”

“Where is the tarp that was in the garage?” Crowell asked.

“What tarp?” Marlon replied.

“The heavy canvas you used for the truck,” Crowell said.

“I don’t know,” Marlon said. “Probably tore, got thrown out. It’s been years.”

“How did your stepdaughter’s locker key and backpack charm end up buried in soil from your construction site?” Crowell asked quietly. “She didn’t have access to that property.”

“I don’t know nothing about that,” Marlon said. “Maybe somebody else—”

“Who else had keys?” Crowell cut in. “Who else drove your truck? Who else had a reason to think putting something out there would hide it?”

He left the questions on the table. Marlon didn’t pick them up.

When the interview ended, Crowell had no confession. What he had was a series of facts that didn’t shy away.

He sat down and wrote out a reconstruction of the day from all the evidence.

Late afternoon, April 1987: Between 4:30 and 5:00 p.m., neighbors heard a loud argument at the Porter house. Voices identified: Chenise and Marlon. Lydia verifiably at work.

The argument ended with a slam. No one saw Chenise leave. No one saw her outside. No one heard another teenage voice for the rest of the evening.

Investigators now believed that in that window, something irreversible happened inside the house. A shove. A blow. A fall. Without a body, they couldn’t put exact words on it. But the lack of struggle signs—the fact that her shoes and jacket were left, that nothing in the house was torn apart—suggested it was sudden, not prolonged.

Marlon would have realized quickly that she wasn’t getting back up.

He had hours before Lydia’s shift ended.

He went to the garage, took the heavy tarp used to cover loads. He wrapped Chenise’s body, tight, and carried it out the back to his pickup, parked where neighbors wouldn’t see easily. He loaded the bundle into the truck bed.

He grabbed her school backpack, maybe from near the desk, maybe from the hallway, and tossed it on the passenger seat. A detail that would be seen later—if anyone saw the truck that night—that could hint she’d “just left.”

Around 7:15 p.m., he drove away. No one reported seeing Chenise. No one even knew to look.

He drove first to the bar on Riverside, four miles away. Around 8:30 or 9:00 p.m., he walked in, ordered his one drink, sat there looking like a man with too many thoughts and not enough words, vented a little to Barney about “disrespect” at home, and left.

At that point, his jacket was still clean. No clay.

From Riverside, he headed out toward the construction site on the industrial fringe—another fifteen minutes.

With his key, he opened the gate and drove the truck in, moving toward the back where the fresh piles of fill lay, red and damp. No cameras. No lights beyond what his headlights offered. No one to ask what he was doing there.

He parked, unloaded the wrapped body, and carried or dragged it to a shallow depression in the clay—left by some earlier excavation. He laid her there, unrolled enough of the tarp to situate her, then began covering her with soil. First fine, then heavier clumps. No more than three feet deep. Enough that a casual glance wouldn’t see it.

Then he took her backpack, walked a short distance, dug a smaller hole, and pushed it in. Maybe he thought it best separated from the body. Maybe he just didn’t want it in the cab anymore.

Over the next days and months, bulldozers would push new loads over that area. The depression would vanish. The temporary grave and the backpack would sink deeper with each pass of heavy machinery.

He closed the gate on his way out sometime after 10:00 p.m., his jacket now smeared with fresh red clay, his truck tires carrying red‑brown smudges on their treads.

He drove home, arriving around 11:30 p.m., just as Lydia was starting to understand something was wrong.

Hinged sentence: Crowell’s reconstruction didn’t rely on imagination so much as on simple geometry—lines between points, each point backed by a witness, a record, or a lab result, all converging on one man with one key.

The county prosecutor’s office agreed. They filed charges. Even without a body, the chain of evidence was strong enough.

The trial of Marlon Doyle wasn’t televised. There were no national headlines. But in Knoxville, people who’d glanced at that curling missing poster for seven years took notice.

In the courtroom, a forensic scientist explained soil like a language.

“We analyzed the sample from the jacket,” she said, pointing at a chart. “Then we analyzed core samples from forty‑two points on the former construction site. The sample from the jacket matches the composition of soil in the area where the backpack fragments were found across multiple factors—mineral content, grain size, oxidized iron levels, trace elements. It’s not a general ‘red clay’ match. It’s specific.”

“So the soil could have come from somewhere else?” the defense asked.

“Not with that profile,” she answered.

Construction company records were introduced, highlighting key assignments and after‑hours policies. Derek Collins testified that yes, late‑night checks were normal for someone in Marlon’s position. No, nobody else had a reason to use his keys.

Barney took the stand, hands clasped awkwardly, to describe the nights at the bar.

“He was mad,” Barney said. “About the girl. About home. Then he left. I thought he was just blowing off steam. Wish I’d paid more attention.”

Lydia testified about the missing tarp, about the jacket.

“That clay was wet,” she said. “He came in like he’d been in a ditch. But he said he just checked equipment.”

City engineers confirmed how the land had changed, how fill from the original site had been moved and layered, how impractical it would be to go back now and dig without tearing apart an entire warehouse and parking lot.

The defense pointed to the lack of a body.

“You can’t say how she died,” the attorney argued. “You can’t say for certain she’s even dead.”

“She was fifteen,” the prosecutor said in closing. “She didn’t have access to cars or construction sites. She left her jacket. Her bank account was never used. No calls, no letters, no credible sightings in seven years. Her locker key and backpack charm were found buried in soil her stepfather had fresh on his jacket that night from a site he alone could freely access. The law does not require a body when the evidence tells the story.”

After deliberating, the jury returned its verdict: guilty of second‑degree murder.

The judge sentenced Marlon to twenty‑five years in state prison. Parole eligibility would depend on the statutes in effect at the time of sentencing.

Hinged sentence: In the end, what put Marlon behind bars wasn’t a dramatic confession or a hidden witness—it was a jacket Lydia couldn’t stop thinking about and a little metal key that refused to stay buried.

For Lydia, the sentence didn’t bring her daughter back. It didn’t tell her exactly what had happened in that split second when an argument turned into something else. But it did give shape to the void that had hung over her for seven years.

The faded missing poster on the precinct board was finally taken down. In its place, at least on the inside of the department, there was a different kind of marker: a closed case file whose path to closure had started with routine land work and the choice of one mother to keep a stained jacket when everything else was slipping away.

Years later, Crowell would look back on it as a reminder that time doesn’t always erase evidence. Sometimes it preserves it in the least likely places—under a warehouse parking lot, inside the weave of an old canvas coat, or in the memory of a bartender who noticed how fast a man finished one cheap drink before heading out into the night.

News

When Your Friend 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐥𝐬 You To Steal Your Unborn Child | HO!!

When Your Friend 𝐃𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐥𝐬 You To Steal Your Unborn Child | HO!! In the early 2000s, the Franklin family was…

He Took A Loan Of $67K For Their Baby shower, He Discovered that It Was A Scam, There Was No Baby &- | HO!!

He Took A Loan Of $67K For Their Baby shower, He Discovered that It Was A Scam, There Was No…

Billionaire Married a 𝐅𝐚𝐭 Girl For a Bet of 5M $ But Her Transformation Shocked Him! | HO!!

Billionaire Married a 𝐅𝐚𝐭 Girl For a Bet of 5M $ But Her Transformation Shocked Him! | HO!! One I…

I acted like a poor and naive mother when I met my daughter-in-law’s family — it turned out that… | HO!!!!

I acted like a poor and naive mother when I met my daughter-in-law’s family — it turned out that… |…

Why Did Louisiana’s Most Dangerous Slave Let Two White Women Into His Bed on the Same Night? | HO!!!!

Why Did Louisiana’s Most Dangerous Slave Let Two White Women Into His Bed on the Same Night? | HO!!!! November…

Husband Walks Out During Family Feud – What His Wife Did Next Made Steve Harvey LOSE IT | HO!!!!

Husband Walks Out During Family Feud – What His Wife Did Next Made Steve Harvey LOSE IT | HO!!!! Every…

End of content

No more pages to load