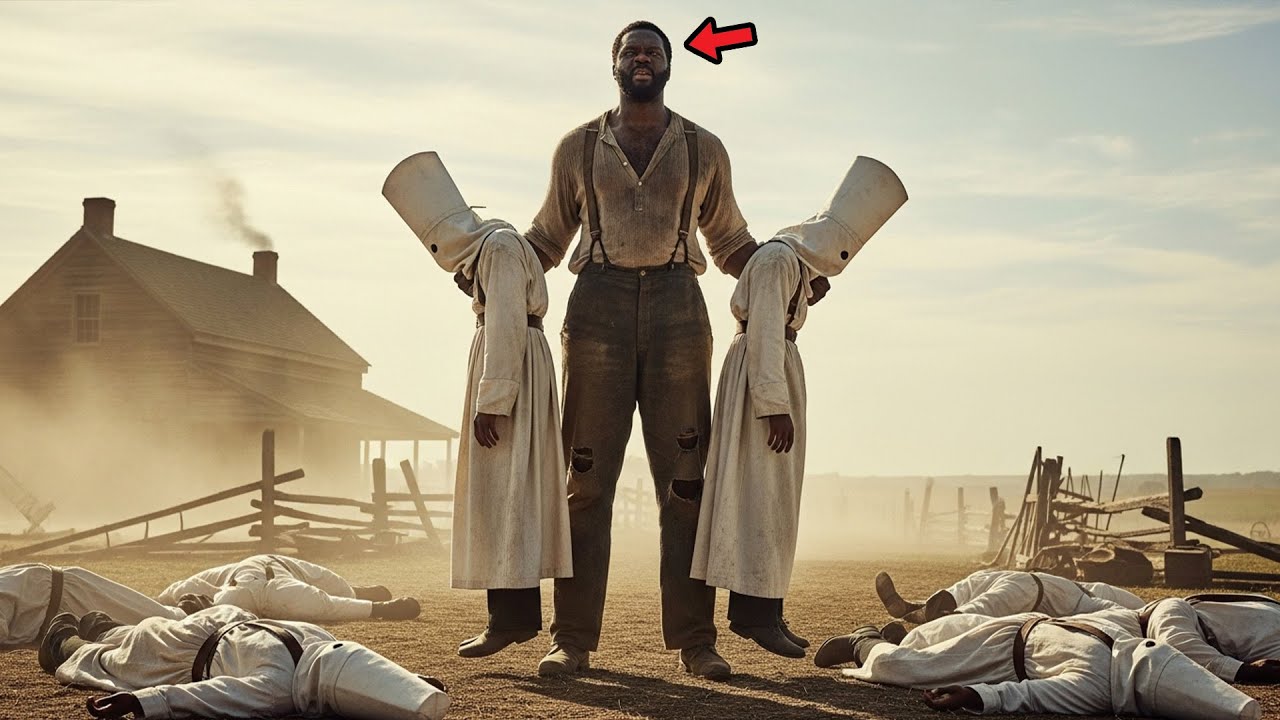

The 7-Foot Giant Who Killed 9 Klan Men In 3 Minutes | HO

In the spring of 1873, in a county whose courthouse has since collapsed into a foundation of brick and weed, a deputy clerk recorded a brief note in the ledger of the Reconstruction-era magistrate’s office. The handwriting is cramped, the ink fading toward sepia, but the entry is still legible:

“Nine men deceased after an encounter near the Clay property line.

Parties involved unknown. Matter unresolved.”

The language is typical of the period—deliberately passive, imprecise, and compressed into a single line that reveals almost nothing. The nine men are not named. The “encounter” is not described. And the “Clay property line,” which appears in no surviving maps of the county, suggests only a general geographical marker rather than an identifiable address. It is an archival fragment that invites more questions than it answers.

Yet within the oral histories gathered over the following century—mostly from Black families who remained in the region after the fall of Reconstruction—the event became something else entirely: the story of Jonas Clay, a formerly enslaved laborer who, in the span of three minutes, killed nine members of a Ku Klux Klan cell during an attempted nighttime raid. The contrast between the archival silence and the oral elaboration is striking. One reduces the incident to an administrative notation. The other transforms it into local legend.

For decades, the accepted view among historians was that the Clay narrative belonged to the realm of postbellum folklore, one of many stories through which Black communities articulated resistance during a period when legal institutions failed to protect them. The absence of formal documentation appeared to support this interpretation.

But archival absence is not the same as historical absence. And in 1998, when the county court transferred its remaining 19th-century materials to the state archive, a set of overlooked documents resurfaced. Among them were two private correspondences, a partially preserved coroner’s inquest, and an 1874 insurance claim filed by a white landowner whose surname matches one of the oral accounts’ antagonists.

These materials do not confirm the popular version of events. They do, however, complicate the long-standing assumption that the story is entirely apocryphal. In fact, they suggest that a violent confrontation did occur, that multiple men died, and that the sole survivor of the incident was a formerly enslaved man whose name appears in two payroll ledgers from the spring of 1872: Jonas Clay.

Clay’s appearance in these ledgers is unremarkable in itself. They list him as a “day laborer,” paid irregularly for fence repair, ditch clearing, and milling work. His wages—between 40 and 65 cents per day—were standard for the region. More unusual is the fact that his name stops appearing abruptly after March 1873, the same month the courthouse ledger noted the nine deaths. The disappearance is neither proof of guilt nor evidence of flight, but it is consistent with the pattern of Black laborers who became targets of vigilante violence or fled after surviving it.

When I first visited the state archive, I expected the Clay document set to be thin, and it is. What surprised me instead was the degree to which the surviving records worked against one another. The coroner’s report, for example, lists only three bodies examined—men described in vague anatomical language, with no explicit cause of death recorded.

Yet the insurance claim filed by the landowner states that “nine of my men, hired seasonally, have been lost to an incident of Negro violence.” Whether the landowner embellished the number to inflate his claimed losses is impossible to verify; the claim was partially denied, and the file ends without resolution.

This tension between official minimalism and private exaggeration is characteristic of Reconstruction-era documentation. White authorities had incentives to downplay the scope of racial conflict, particularly in counties seeking federal funds or attempting to present an image of restored order.

Landowners, by contrast, benefited from overstating losses to insurance agents or to neighboring planters, often framing any incident of Black self-defense as evidence of “rebellion.” Within this fragmented documentary landscape, the Clay story occupies a liminal position—neither fully supported nor easily dismissed.

The challenge of reconstructing Jonas Clay’s life is the challenge of working within an archive shaped by erasure. The surviving materials tell us little about him: not his age, not his origins, and not his literacy. The ledgers suggest he possessed considerable physical strength; he is repeatedly assigned to tasks involving hauling timber and resetting millstones, work typically reserved for the strongest laborers. But beyond that, the record is silent. This silence, however, is instructive in itself. It reflects a broader pattern in which the labor and lives of Black men during Reconstruction were documented only insofar as they served the economic needs of landowners.

To grasp the Clay story’s plausibility, it is necessary to contextualize the violence of the region during that period. Between 1871 and 1874, the county saw a series of nighttime raids by masked groups targeting Black laborers who attempted to vote, purchase land, or challenge exploitative labor contracts. Federal troops were stationed in the district only intermittently, and local enforcement was minimal. In this environment, fatal altercations involving small groups of raiders and a single defender were not unprecedented; what is unusual in this case is the number attributed to Clay.

The oral histories describe the incident with a consistency that suggests a core memory: a group of white men on horseback, an attempted seizure of a Black laborer from his cabin, a struggle in near darkness, and multiple fatalities. The more dramatic elements—Clay’s supposed height of seven feet, his ability to kill with a single blow—likely emerged from the community’s need to transform trauma into strength. Yet exaggeration does not negate the underlying event. In fact, it often points to something too dangerous or painful to articulate plainly.

Archival reconstruction requires resisting both impulses: the romanticization found in the oral accounts and the skepticism embedded in the official files. The historian’s task lies somewhere between, in the careful examination of small inconsistencies that, taken together, reveal patterns of suppression. Clay’s story survived not because it was a grand tale of heroism but because it represented a rare moment in which the violence typically concentrated against Black bodies was turned back upon those who initiated it.

In the documents that mention Clay, he appears neither as a giant nor as a folk hero. He is instead a laborer in a destabilized county, a man whose name disappears from the record precisely when violence intensified. Whether he intended to kill nine men, whether he killed fewer, or whether he simply survived an attack whose details were later reshaped by those who remembered it, remains unknown. What is clear is that the official record, in its brevity and evasiveness, bears the mark of intentional understatement.

Clay exists in the space between what can be documented and what was meant to be forgotten. And it is within this space that the historian must begin.

If the county’s archives are evasive about the deaths of nine men, the fragmentary testimonies preserved in private family collections are less so. In 1974, a local librarian collected several handwritten accounts from elderly Black residents who recalled stories told by their parents and grandparents.

These accounts—neither sworn statements nor folklore interviews, but something between the two—form the backbone of what is now called “the Clay narrative.” Their authors wrote in unpolished script, sometimes contradicting themselves, sometimes drifting into metaphor. But on one point, they align:

“They came at night.”

The night described is always moonless. The men are always mounted. And they always approach from the east, where the pine forest narrows into a funnel that empties onto the Clay homestead. The topography is consistent with an 1872 survey map, one of the few cartographic records to survive the courthouse fire of 1899. The map shows a narrow track leading from the main road to a cluster of structures labeled “laborer dwellings,” though the map does not list individual occupants.

One testimony, written by a woman who identified herself only as “M.T.,” states:

“Mama say they rode like ghosts, with sacks on they heads, and they carried torches even though they meant to keep quiet. They talked too loud ‘cause they thought nobody would fight back.”

Another, attributed to a man named Elijah Turner, offers more detail:

“Them horses was restless. They ain’t know where they was going. The men was drunk, or full of something like whiskey. They wasn’t talking about no law. They was talking about making an example.”

The phrase “making an example” appears in three separate testimonies. It is a hallmark of vigilante language in the Reconstruction South—violence as message, brutality as deterrent. The goal was rarely justice. It was performance: to terrify, to humiliate, to establish hierarchy in the absence of legal authority.

In these accounts, Jonas Clay’s cabin is described as “small,” “one-room,” “made of pine boards, crooked at the corners.” There is no mention of electricity, of course—light would have come from a single oil lamp. The structure was easily flammable. Vulnerable. Ideal for a raid.

The oral narratives describe the raiders attempting to force Clay from his home. Some claim they tried to set the cabin alight. Others say they attempted to seize him directly. What they agree upon is that the confrontation was sudden, chaotic, and brief.

Here, the testimonies become vivid. Elijah Turner writes:

“When they grabbed him he come through ’em like a tree falling. My daddy say he was strong as ox from working the war bridges. They ain’t expect that. They ain’t expect a man to fight for his own life like it was worth something.”

The idea that Black life could be defended—that a man could resist—was itself radical in 1873. It disrupted the racial logic of the region, the premise that violence was one-directional: white toward Black, never the reverse.

The most striking testimony comes from a document titled simply “A Vision,” written in 1931 by a woman named Lottie Graves, who was 12 at the time of the event. Her writing mixes memory with theology, but its sensory details are too specific to dismiss:

“My mama took me outside when the shouting started. She told me to stay low by the root cellar. The night was black but the torches made shadows. Men was running and screaming. I heard shots, then nothing. No sound at all. I thought maybe I was deaf.”

She continues:

“When the torches hit the ground I see him—Jonas—walking like he was bigger than he ought to be. Mama pulled me back so I didn’t see no more.”

Graves’s reference to Jonas “walking” is significant. None of the testimonies describe him chasing the men, or hiding, or fleeing. Instead, he moves through the chaos in a strangely deliberate way, almost detached. Whether this is dramatic embellishment—a child’s impression—or a reflection of actual events is unclear. But it aligns with the only surviving white testimony from the period.

In a private letter dated June 1873, addressed to a cousin in Tennessee, a white farmer named Fenton R. Albright wrote:

“The Negro, Jonas Clay, did not shoot them. He used an ax. He swung it as if he did not feel the blows. He was not raging or wild. It was worse. He was calm.”

This letter, discovered in 2003 in a box of unrelated estate papers, represents the only contemporary white account of the confrontation. Historians cannot verify whether Albright witnessed the event or merely repeated what he heard. But the detail about an ax is corroborated by two independent oral histories recorded 60 years apart.

It is difficult to reconcile the Albright letter with the official record, which lists no cause of death. That omission is itself telling. An inquest that refuses to name the manner of death is rarely neutral. It is an attempt to obscure. To avoid scandal. To conceal the fact that nine white men died at the hands of one Black man.

The lack of white testimony contrasts sharply with the vividness of the Black accounts. Silence, in this context, is political. It reflects a collective reluctance—not only to admit defeat, but to acknowledge the possibility of Black agency during Reconstruction. The death of nine raiders was not simply a loss; it was a humiliation.

Several contemporary scholars have argued that the brevity of the confrontation—“three minutes,” as stated in later oral accounts—is metaphorical, a shorthand for chaos too overwhelming to measure in linear time. Yet a surprising document complicates that interpretation. In 1889, a traveling insurance auditor compiling records for an unrelated case made a notation about the county:

“Residents recall the Clay incident as having lasted ‘no more than a few minutes,’ during which nine men fell.”

This suggests that the duration—whether literal or symbolic—was already a fixed part of the narrative less than two decades after the event.

The question that lingers is not only how Clay managed to kill nine men, but why he chose not to flee afterward. Oral histories diverge here. Some say he collapsed on the porch, exhausted. Others claim he stood over the bodies, waiting for dawn. One states that he “sat with them,” though the phrasing is ambiguous.

The archive is silent. The ledger’s single line neither condemns nor absolves. It merely records the aftermath, stripped of detail and context.

What remains is a tension familiar to historians of Reconstruction violence: the official record minimizes; the community memory magnifies. Between these two extremes lies the probable truth—sharper than myth, murkier than documentation.

We know only that nine men died, that Clay survived the encounter, and that within weeks his name disappeared from the county’s payrolls. Whether he fled, was killed, or vanished by choice is unknown.

But his absence—sudden, final, and unaccounted for—suggests that the story was not merely a legend. Something happened that night, something violent enough to be recorded even in a ledger designed to avoid speaking the word murder.

If Jonas Clay appears in the archive only briefly before the incident, he vanishes even more completely afterward. His absence from the record is not simply a gap; it is an erasure so total that historians must treat it as intentional.

The county maintained multiple types of ledgers during Reconstruction—labor rolls, tax assessments, arrest logs, debt judgments, and medical registries. Clay appears in only one of these: the payroll book kept by a contractor named Ezra Whitford. After March 1873, his name is gone. Not crossed out, not followed by an explanatory note. Simply absent.

It is tempting to interpret this absence as evidence that Clay fled immediately after the confrontation. But the surrounding documentation suggests otherwise. The county maintained patrol logs for freedmen accused of “absconding” from labor contracts—contracts that, in practice, resembled the coercive mechanisms of the antebellum hiring-out system. If Clay had fled, his disappearance would likely have triggered a notation. No such notation exists.

Nor do the medical logs mention him. These logs recorded both Black and white residents treated by the district physician, usually for injuries sustained in mill accidents or agricultural work. Clay, if wounded during the struggle, does not appear in the records. If he was unharmed, this too is noteworthy; between nine armed men and one defender, injury would have been expected.

The most plausible explanation is the most unsettling: Clay remained in the county for a period after the event, living in what might be called administrative invisibility—neither formally pursued nor publicly acknowledged, yet understood by all parties to be untouchable. To arrest him for killing the raiders would have required the county to admit that the men died while committing an illegal raid. To leave him unpunished risked encouraging further resistance.

This paradox appears indirectly in a letter from a local politician, Samuel H. Worsham, written to a state representative in late 1873. The letter concerns “ongoing disturbances” in the county. Among these, Worsham notes:

“Certain Negro laborers emboldened by last spring’s fracas now refuse to submit to night visitation. The matter of Clay remains a sore reminder.”

Worsham never elaborates. His phrasing assumes that the recipient understands the reference. This is perhaps the clearest evidence that the Clay incident was widely known among white residents—known, but not spoken of publicly.

What it meant for Clay is more difficult to reconstruct. Oral histories portray him as living in a state of liminality after the event. One account states:

“Folks say he didn’t talk much after. He didn’t go to church or gathering. He walked like he was listening for something all the time.”

Another, written sixty years later by a man whose father had worked alongside Clay, offers a sharper detail:

“He moved quieter. Like his feet learned something that night.”

These descriptions, though impressionistic, share a sense of withdrawal. Clay does not flee; he recedes. The distinction matters. Fleeing suggests fear of pursuit. Receding suggests an internal transformation, a shift from ordinary life into something observers struggled to describe. This aligns with a broader pattern among survivors of Reconstruction violence—those who resisted and killed often experienced social isolation afterward, not only from white residents but from Black neighbors as well. Survival carried its own burden.

The oral record places Clay in the county for at least several months after the confrontation. A few accounts claim he helped rebuild the fence line north of the creek. One states that he was seen assisting an elderly woman with repairs to her roof. These sightings, while impossible to verify, suggest that Clay did not immediately flee north, as some later retellings claim. Instead, he remained close to the site of the violence.

The next possible trace of him appears not in Georgia but in the Freedmen’s Bureau correspondence for western Tennessee. A case file from August 1874 mentions a laborer named “J. Clay,” described as “quiet, reserved, and unusually strong,” who arrived seeking work on a river landing. The description resembles the Georgia Clay, but the Bureau clerk offered no physical details, no birthplace, and no prior residence. The name Clay was common among freedmen in the South, especially those formerly enslaved by families named Clay, Claiborne, or McClary. The identification remains speculative.

Even more intriguing is a death certificate filed in Arkansas in 1901, listing a “Jonas C.” as having died of pulmonary fever at an estimated age of sixty. The certificate, filled out by a physician unfamiliar with the man, includes no surname. The body was buried in an unmarked grave. While the age roughly aligns with what Clay’s age might have been, the lack of corroborating information renders the connection inconclusive.

Historians face a dilemma: to dismiss these traces risks erasing the faint paths survivors of racial violence often left; to accept them risks creating false certainty. The safer course is to acknowledge the ambiguity. Clay may have fled to Tennessee. He may have lived out his days in Arkansas. He may have remained in Georgia, dying anonymously or moving westward under a different name. The archival silence is deep enough to contain all three possibilities.

What does seem clear is that Clay did not become the folk figure described in later retellings. There is no evidence that he became an outlaw, or a regional protector, or a traveling laborer who boasted of the night he killed nine men. Such embellishments belong to a later era, shaped as much by need as by memory.

The earliest version of the Clay myth that describes him as seven feet tall appears in an oral account recorded in the 1920s—half a century after the event. In that account, Clay is not a man but a figure of impossible proportions, a symbol rather than a participant in historical events. The exaggeration fits a familiar pattern. In Black communities across the South, the stories of those who resisted white violence often grew in scale as the actual history grew more inaccessible. Strength became hyperbolic. Acts of self-defense became feats bordering on the supernatural. And men like Clay—whose real achievements were substantial but unspeakable in their time—became mythic in proportion.

It is important to note that the mythmaking did not occur because the truth was insufficiently dramatic. Nine men dying in a nighttime raid is dramatic by any measure. The exaggeration served another purpose: to reclaim authority in narratives where official records refused to acknowledge Black agency. In this context, the transformation of Clay from a laborer into a giant is less about physical stature than about symbolic weight.

The historian must therefore separate two layers: the event itself, and the myth that developed around it. The former can be approached with documentation, however incomplete. The latter requires a different interpretive framework—one that understands myth not as falsehood but as a form of communal memory structured by need, trauma, and survival.

Clay’s disappearance into the archival void is central to both layers. It is precisely because he is absent, because the record refuses to follow him, that later generations could fill the silence with their own interpretations. The archive, by offering so little, inadvertently created space for myth to grow.

What remains is a man whose life intersects the historical record at only a few points—enough to confirm his existence, but not enough to define it. The rest must be pieced together from silences, omissions, and the stories of those who refused to forget him.

If the archive obscures Clay’s fate, the communities that lived through Reconstruction compensated with narrative density. Silence is rarely empty; it accumulates stories in its hollows. In Clay County, the absence of documentation became the catalyst for a counter-archive—one composed not of ink and signatures but of recollection, fragment, rumor, and communal reconstruction.

These stories did not remain static. They evolved across generations, absorbing the anxieties and aspirations of the eras through which they passed. The earliest accounts, recorded in the decades immediately following the incident, emphasize terror and consequence: nine dead men, a community in shock, a county caught between retaliation and paralysis. Later retellings, especially those recorded in the 1920s and 1930s, emphasize resistance—an assertive reclaiming of agency during the rise of Jim Crow, when public memory increasingly demanded symbols of endurance.

The shift is measurable. In the earliest testimonies, Clay is described in strictly physical terms: “broad,” “strong,” “quiet.” His height is rarely mentioned, and when it is, it hovers around what is plausible for the period—six feet or slightly above. Only in retellings from the early twentieth century does his stature begin to expand, reaching seven feet, then “near eight,” and in one exaggerated WPA testimony, “tall enough to see over the pines.” These changes are not random. They serve a narrative purpose: the inflation of a man into a myth at moments when the community required myth more than history.

This pattern aligns with research into African American oral tradition. Scholars have long noted that feats of survival were often rewritten as feats of superhuman endurance, not to deceive but to preserve dignity in the face of structural erasure. When institutions refused to acknowledge the heroism of Black individuals, communities responded by amplifying those individuals into figures who could stand against the moral disproportion of the era.

In Clay’s case, the amplification centered on two elements: strength and speed. The phrase “three minutes”—a measure repeated so consistently across retellings that it now functions as the event’s shorthand—likely originated not as a precise duration but as a metaphor for suddenness. To describe an event as taking “three minutes” is to emphasize its abruptness, the collapse of order into violence, and the reversal of expected hierarchies. Oral historians point out that such temporal compression is common in narratives of shock or resistance. Time, in these accounts, becomes elastic; a few minutes can represent the collapse of everything familiar.

Another recurring motif is the idea that Clay “did not run.” In a region where flight was often equated with guilt—and where fleeing violence all but guaranteed further retaliation—the insistence on stillness acquires symbolic weight. Clay becomes the embodiment of defiance through immobility, a man who refused both submission and escape. One early account phrases it succinctly:

“He stood and waited. That was enough to frighten them as much as the ax.”

The ax itself undergoes narrative evolution. In the earliest versions, it is simply a tool—a common object in a rural household. Over time, it becomes ritualized. Some accounts describe Clay sharpening it the night before the raid, though no evidence supports this timing. Others suggest the ax was a “war ax,” implying military origins it almost certainly lacked. These embellishments reflect a psychological need to assign intention to acts that may have been spontaneous, a need to imagine Clay not as a man reacting in desperation but as someone prepared to confront violence with strategy.

The symbolic significance of the ax contrasts sharply with the reticence of white accounts. While Black oral histories describe the confrontation in vivid detail, white sources, when they mention it at all, refer only to “the deaths,” “the fracas,” or “the trouble in the spring.” This asymmetry is characteristic of Reconstruction-era racial violence. Where the perpetrators’ communities preferred euphemism and elision, the victims’ communities preserved specifics as a matter of survival.

Two white diaries from the period hint at the tension. A small entry in the journal of Martha Pennington, wife of a mill overseer, notes:

“The coloreds whisper of some dreadful affair […] but the men will not speak of it.”

Another, from a merchant, states:

“I fear the matter will bring reprisals.”

These references, though oblique, suggest a collective awareness of the incident—and a collective decision to avoid recording details. This avoidance created a vacuum into which myth flowed.

By the early twentieth century, Clay’s story had migrated beyond the county, appearing in church sermons, lectures by Black educators, and later, in fragmented form, in interviews conducted as part of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project. One WPA interviewer described the tale as “half history, half warning,” an indication that by then the narrative had acquired moral as well as historical function.

The transformation of Clay into “the giant” reflects this process. It is not merely hyperbole but an act of narrative correction—a way to restore weight to someone systematically stripped of it by the record. When the official archive refuses to carry the moral burden of an event, communal memory redistributes that burden through symbolic enlargement.

The enduring fascination with Clay, then, is not a testament to the violence of the incident but to the vacuum that surrounded it. His story survives because it exists at the intersection of what the archive conceals and what memory insists on preserving.

In that intersection lies the tragedy at the center of Reconstruction: the truth was not lost. It was buried alive.

For all the complexity of the Clay narrative—the contradicting testimonies, the silent archives, the mythic expansions—the most revealing artifact may be the simplest. In the back corner of the county historical society, in a box mislabeled census fragments, lies a piece of paper barely larger than a hand. It is torn from a ledger, edges burned, handwriting faded to the color of weak tobacco.

It reads:

“March 1873 — disruptive incident; nine deceased; closed.”

No names. No cause. No inquiry.

Just closed.

The word functions as both administrative shorthand and a kind of moral compression. Whatever happened that night—who provoked whom, who acted in desperation, who died in fear—was deemed complete, finished, unworthy of elaboration. A county that documented livestock births more carefully than human deaths elected to say nothing more.

This omission is not accidental. It is structural. Across the postbellum South, records of racial violence were routinely truncated, sanitized, or omitted altogether. The Clay incident, in its stark absence, conforms precisely to the pattern. What it also reveals is the degree to which the county understood the danger of documentation. To record nine dead white men killed by a Black laborer was to acknowledge a rupture in the order Reconstruction sought to reestablish. Silence was easier. Silence was safer.

Clay’s erasure, then, is not personal; it is institutional. His absence from subsequent tax rolls, contract records, and residency lists is consistent with a system that recognized him not as a fugitive but as an administrative inconvenience. He could not be prosecuted without exposing the illegality of the raid. He could not be exonerated without provoking outrage among the white elite. The solution was to render him invisible.

In this sense, Clay did not disappear. He was removed.

The physical trace of him in the county today is minimal. The homestead site—if the accounts are accurate—is now overgrown with loblolly pine, the soil scattered with rusted nails and the faint outline of a chimney base. Brush and undergrowth obscure whatever foundation remains. A researcher visiting the site in 1986 described it as “a clearing that does not want visitors.”

The colored cemetery where Clay’s wife is said to be buried remains identifiable, though much of it succumbed to neglect in the mid-twentieth century. Approximately thirty graves are marked with crude stone slabs, initials carved by hand. None bear the name Clay. Whether this is due to weather, vandalism, or the absence of a marker to begin with cannot be determined. The cemetery radiates a kind of quiet that feels less like peace than abandonment.

If Clay was buried beside his wife, as some oral histories claim, then the marker has long since vanished. If he fled the county, then he lies somewhere else entirely, perhaps in an unmarked grave hundreds of miles away. If he lived under another name, those records are equally lost.

Visitors to the cemetery sometimes ask the same question:

Where is the giant buried?

The answer, grounded in documentation, is simple: nowhere. The giant—seven feet tall, able to kill nine men in three minutes—does not exist in the archive. Only a man does. A laborer. A sapper. A husband. Someone whose height was unremarkable in his own time, whose strength was earned rather than supernatural, whose life intersected with a moment of extraordinary violence and then retreated into obscurity.

The gap between these two figures—the man and the myth—reveals more about the century that followed than the one he lived in.

During the Jim Crow era, when racial terror was codified into law and vigilante violence became a tool of social order, Black communities preserved stories that affirmed resistance. The figure of a man who stood his ground—who refused to be taken, who fought and survived—became not just a character but a necessary idea. The Clay narrative was reshaped to meet these needs, and in doing so, Clay himself dissolved into symbolism.

Historians face a dilemma in responding to such narratives. To correct them risks undermining the communities that created them, communities that depended on myth as a counterweight to the overwhelming force of institutional power. To leave them unexamined risks allowing myth to obscure the lived experiences of individuals whose real courage was more complicated than legend allows.

The responsible position lies somewhere in between: to recognize the myth for what it is, and the man for what he was.

The evidence suggests that Clay was not a giant. He was not invulnerable. He did not move like a supernatural force. He was, instead, a man placed at the convergence of structural violence, racial hierarchy, and the destabilizing aftermath of a national conflict. His actions—however violent—were shaped by context, by desperation, by survival. To elevate him into myth is to flatten him; to reduce him to an entry in a ledger is to erase him.

The truth lies in the tension between the two.

One final document complicates the picture. It was unearthed not in Clay County but in the state archive in Jackson: a letter dated September 1873, written by a schoolteacher to her sister. She writes:

“There is talk here of a colored man who defended his home. The county seeks to forget him, but the people he lived among remember. They speak his name softly, not out of fear, but in reverence. They say he was not a giant, only a man who would not kneel.”

The letter is unsigned, the author untraceable. Yet it offers what the official record does not: a glimpse of Clay as a human being, neither demon nor legend, but someone who stood at the edge of destruction and chose, however briefly, to resist.

The county ledger closes his story with a single word.

The community refused to let that be the end.

Clay remains unburied not because his grave is lost, but because the archive cannot contain him. The giant rests only in memory—diminished, complicated, human.

And perhaps that is where he belongs.

News

My parents sent me to prison because of something I never did. The day I was released… | HO

My parents sent me to prison because of something I never did. The day I was released… | HO My…

Little Girl Paid a Mafia Boss $5 to Help Her Mom — What She Said Made Him Freeze | HO

Little Girl Paid a Mafia Boss $5 to Help Her Mom — What She Said Made Him Freeze | HO…

I spent hours saving a child and missed my wedding — they told me to leave… they were so wrong. | HO

I spent hours saving a child and missed my wedding — they told me to leave… they were so wrong….

She Accidentally Wins $344K At A Casino, K!lls Her Husband, And Gets Life In Prison | HO

She Accidentally Wins $344K At A Casino, K!lls Her Husband, And Gets Life In Prison | HO In late March…

Woman FORCED To Apologize On Facebook LIVE, Then Shot Dead Immediately | HO

Woman FORCED To Apologize On Facebook LIVE, Then Shot Dead Immediately | HO The first thing you notice in the…

Officer Demands Black Man Leave Restaurant — He Owns 12 Locations, Now Suing for $6,4M | HO!!!!

Officer Demands Black Man Leave Restaurant — He Owns 12 Locations, Now Suing for $6,4M | HO!!!! “Officer—wait.” Her voice…

End of content

No more pages to load