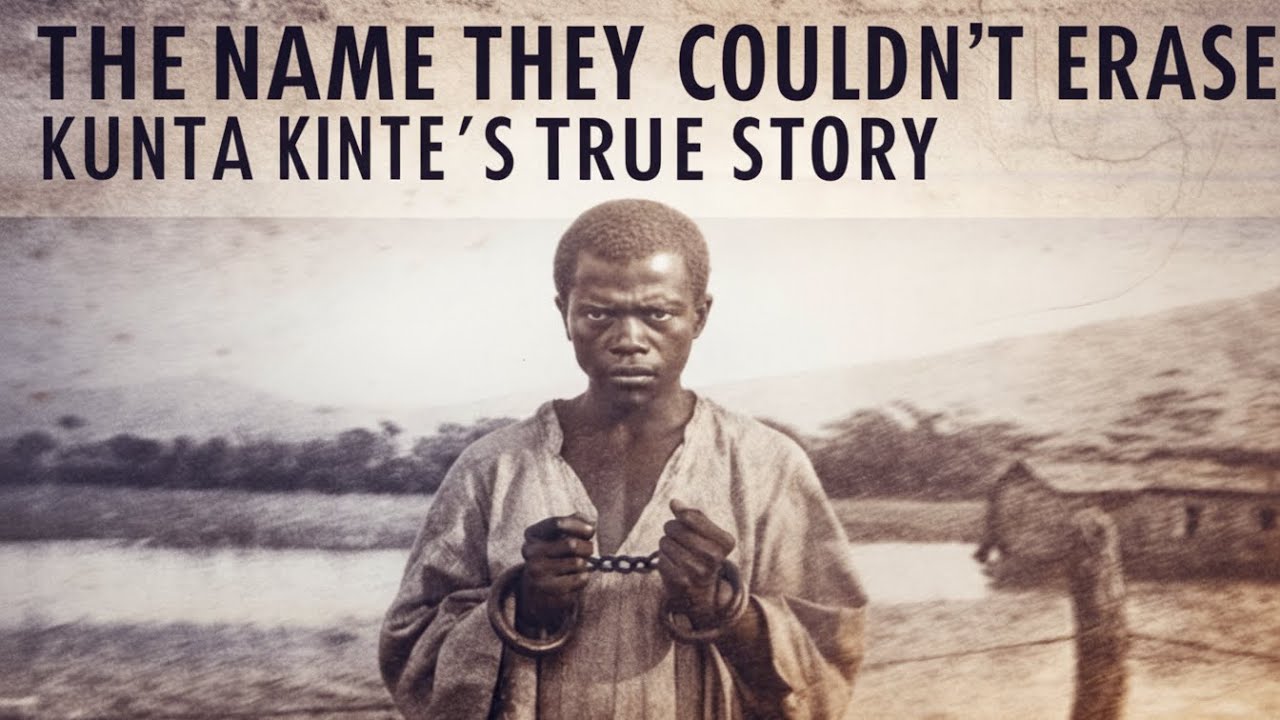

The African Slave KUNTA KINTE The True Story America Never Wanted Told | HO

The archive room smelled like paper and old paste, the kind of quiet that makes you hear your own pulse. On a metal filing cabinet someone had stuck a tiny US flag magnet, a bright modern thing clinging to a century that didn’t want to be touched. A researcher’s iced tea sat sweating onto a coaster, and faint Sinatra drifted from a guard’s radio down the hall—out of place, almost rude, against the brittle hush of documents stamped with dates like verdicts.

On the table lay a shipping manifest page, creased and smudged, the ink faded but still legible where it mattered most. It named a vessel, a harbor, a count: 98 Africans arriving in Annapolis on September 29, 1767, aboard the Lord Ligonier. It also hinted at the missing, as if loss could be summarized. 42 had perished during the crossing. Somewhere between those numbers lived a seventeen-year-old Mandinka warrior who would spend the next fifty-five years refusing to forget his name.

Some histories don’t disappear. They get buried under paperwork.

Records from what was then Spotsylvania County, Virginia, show a human being purchased that October and assigned the name “Toby.” That entry sits in ledgers as if it’s ordinary commerce, as if a name can be handed out like a tool. What those records don’t show—what plantation books omitted and family Bibles refused to acknowledge—was the methodical campaign to erase not just one man’s identity, but the living memory of an entire culture.

This is the story of how one African transformed the brutality meant to break him into a legacy that outlasted his captors, and why so much of it remained obscured by nearly two centuries of silence. What you’re about to read is far more disturbing than the tidy version America grew comfortable telling itself, because the truth isn’t only what happened—it’s how normal it was allowed to be.

The Gambia River cut through West Africa like an open vein, carrying European ships deeper inland than any other waterway along that coast. By 1767, the trading outpost on James Island had processed tens of thousands of captured Africans, and demand from Virginia tobacco plantations had surged into something ravenous. Wars between local kingdoms created opportunity for raiders, and European buyers paid premiums for young men with warrior training—strong bodies, useful skills, high resale value.

Two miles from the British fort, in the village of Juffureh, the Kinte clan maintained their reputation as blacksmiths and holy men despite the constant threat of raids. The Mandinka people had endured for centuries by mastering the art of appearing cooperative while guarding tradition in private. Children were taught not to linger near the river, not to enter the forest alone, and to run at the first sight of the slates—African raiders who worked with European buyers.

Omoro Kinte understood these dangers better than most. As a blacksmith, he had seen iron become shackles. He had heard stories of villages emptied overnight, of families split and sold to different ships. He taught his eldest son traditional skills of drumming not only as cultural preservation, but as practical knowledge. A young man who could craft instruments might be kept alive aboard a slave ship to steady the captives, to reduce what the traders called “loss.”

The boy’s name carried weight. Kunta meant complete, whole—a name given to firstborn sons expected to carry on the family’s legacy. At seventeen, he had completed manhood training, learned to hunt with a spear, and could recite his lineage back seven generations. Village elders spoke of him as someone who would someday become a respected elder himself, a man whose word would carry.

On a morning in early July 1767, Kunta ventured into the forest to gather hardwood for drum making. The trees he needed grew about three miles from the village—far enough to be risky, close enough that young men made the journey regularly. He carried no weapon. Mandinka warriors didn’t hunt on sacred gathering grounds, and he moved with the confidence of someone who knew these paths since childhood.

What Kunta didn’t know was that British Colonel O’Hare’s forces had arrived at James Island three days earlier with orders for a large shipment to fill Virginia’s labor shortage. The Lord Ligonier sat anchored offshore, its captain under pressure to fill a capacity of 140 captives before weather turned. Networks of raiders had been mobilized, offered bonuses for young males between fifteen and twenty-five.

Four slates tracked Kunta from the moment he left the village. They were professionals, men who had perfected ambush over dozens of captures. They knew to strike quickly, to silence a target before any shout could travel, to bind a body so thoroughly that resistance became useless.

The attack happened with terrifying efficiency. The first blow came from behind. Before he could call out, hands closed over his mouth while others pinned his arms. Rope tightened around wrists, cloth muffled sight and sound. In less than two minutes, Kunta went from free man to merchandise.

They dragged him toward the river to a holding area where two dozen other captives sat restrained in a temporary enclosure—some from neighboring villages, others transported from inland. All carried the same stunned look, the mind struggling to process how quickly a person becomes property when force and profit agree.

For three days Kunta remained there while raiders collected more captives. Conditions were deliberately harsh: minimal food and water, exposure by day and cold by night, guards who struck anyone who made too much noise. The message was as calculated as the suffering. Resistance equals pain. Compliance equals survival.

When the Lord Ligonier’s crew came to collect their cargo, they brought a British ship’s surgeon, Dr. Thompson, whose job was to inspect bodies for disease or injuries that might reduce market value. The examination was methodical and dehumanizing, conducted with the same attention a farmer might give livestock. Of thirty-two captives presented, he rejected seven. Kunta passed. At seventeen, he was exactly what Virginia tobacco plantations demanded: young, strong, trained in physical labor from years in a blacksmith’s compound.

The British paid the raiders in rum, textiles, and iron bars. Kunta became property of Captain Thomas Davies, recorded in the ship’s manifest simply as “male, approximately 17, Mandinka.” The phrase was short, almost neat. It was also the first step in a process designed to make him forget every word his father had spoken over his name.

The journey from shore to ship happened in small boats that carried ten captives at a time. Sailors handled it with practiced urgency, knowing first sight of the ship often triggered desperate escape attempts. Shackles stayed on. Orders stayed sharp. Time stayed tight.

Kunta’s first sight of the Lord Ligonier revealed the scale of what was happening. This wasn’t one raid. It was an industry refined over decades. The ship was built for human cargo, multiple decks modified to pack as many bodies as possible into the smallest space. Faces peered through openings like trapped shadows. The crew herded the new captives below deck into conditions that defied comprehension.

The lower deck measured roughly five feet high—forcing men to crouch or lie down. Space allocated per person was about sixteen inches wide and six feet long, barely enough to lie flat. Platforms created two levels, doubling capacity. Captives were restrained in pairs at the ankles, additional chains limiting movement, turning every breath into a reminder that survival depended on whoever you were bound beside.

Kunta found himself restrained next to a man named Fanta, captured from a village about fifty miles inland. Their dialects didn’t match perfectly, but shared Mandinka roots allowed basic communication. Fanta, imprisoned longer, understood the ship’s routines: when food came, how to shift your body to avoid cramps, which sailors were most likely to strike without reason.

The Lord Ligonier remained at anchor another week while Captain Davies negotiated for additional captives. Below deck, conditions deteriorated quickly. Food came once per day: beans, yams, occasionally fish, served in communal buckets shared by ten. Water came twice daily in small rations that left everyone chronically thirsty. Waste overflowed. The crew hosed down the deck every three days as if cleaning a stable, not a room full of human beings.

Disease spread fast in the heat and contamination. Fever swept through one section, taking lives with an efficiency as cold as commerce. Dr. Thompson examined the sick, but his job wasn’t care. It was calculation: would this body survive long enough to sell?

On July 5, 1767, the Lord Ligonier departed Africa with 140 captives restrained below deck. Captain Davies recorded satisfaction with the cargo’s “quality” and expected profit. He did not record the systematic cruelty required to maintain control over that many desperate people trapped in nightmare conditions.

The Middle Passage—crossing the Atlantic from Africa to the Americas—typically took six to twelve weeks. The route carried them past the Cape Verde Islands, then across the ocean’s widest stretch, catching trade winds toward the Caribbean and up the North American coast toward Annapolis.

For the captives, the voyage became an endless cycle of suffering punctuated by brief moments on deck. British policy required bringing captives topside once per day for forced movement—thirty minutes, still restrained—ostensibly to prevent muscle loss, really to reduce deaths enough to protect profit. These moments allowed captives to communicate across language barriers, to realize the scale of their collective situation.

Kunta’s warrior training and cultural education felt useless in this context. Courage and honor didn’t unlock a shackle. The torment was methodical: separation from language, uncertainty about destination, weakening from minimal food and water. But Kunta noticed patterns. Sailors who brought food were less vigilant during rough weather. Deck exercise happened at the same time unless storms intervened. The ship’s surgeon rarely entered the lower holds except on inspection days. The routines meant something important: even a machine of suffering relied on habits, and habits could become weaknesses.

A man named Kinteh—who had been a trader before capture—understood fragments of English from dealing with merchants. He listened to crew talk and reported what he learned. The ship was bound for “Naplis,” which some captives recognized as a mispronounced echo of Annapolis. They would be sold to work tobacco plantations. The British expected most to die within ten years under brutal labor.

That knowledge created a terrible dilemma. Some discussed rebellion once enough reached the deck together, but restraints made coordination nearly impossible, and crew were armed. Failure would mean immediate death for everyone involved. The math was cruel: attempt an uprising and likely end quickly, or accept enslavement with a slim possibility of surviving long enough to seize a different chance.

Kunta listened, but he didn’t speak. Omoro Kinte had taught him that warriors choose battles based on the possibility of victory, not on pride. Everything about their current situation made open revolt suicidal. So Kunta filed away every detail, every routine, every weakness. If there was a future moment, he would need knowledge more than fury.

Three weeks into the voyage, fever spread through the lower deck. Men who had survived capture and transport died restrained beside their partners. Bodies remained until crew noticed and removed them. Dr. Thompson recorded each death with clinical detachment. By his measure, a 15% mortality rate was acceptable. 30% required notice. Above 40% brought scrutiny. The dead were not mourned in the ship’s log as lives lost. They were tallied as inventory.

Fanta developed the fever during the fourth week. Chills, headache, delirium. He stayed lucid enough to recognize what was coming. And in a moment of clarity that cut deeper than any blow, he apologized to Kunta for what would happen next.

Two days later, Fanta died, and Kunta spent eighteen hours restrained beside a corpse before the crew removed the body. No new partner replaced him. Instead, his restraint was shortened and attached to the wall, giving him even less mobility. This isolation wasn’t intentional cruelty so much as logistics: they hadn’t captured enough to replace the dead. But it deepened Kunta’s psychological torment. He existed in near sensory deprivation, surrounded by suffering, unable to communicate meaningfully, the hold a darkness that tried to convince him he’d never been anything else.

Just when it seemed the voyage had reached the worst it could offer, the ocean reminded everyone aboard that profit cannot command weather.

In the seventh week at sea, a storm struck—Atlantic weather that tested even experienced captains. The first signs came at dawn: wind shift, clouds building, air turning heavy. Captain Davies ordered the crew to secure cargo and prepare. For the captives below deck, preparation meant nothing changed. Restraints stayed. Positions stayed. Only now the ship began to pitch and roll with violence.

Men were thrown against chains as the vessel lurched. Wooden platforms creaked under shifting weight. Water drove over the deck and down through ventilation grates into the holds. Within hours, several inches of sloshing seawater mixed with overflow, creating a toxic flood no one below could escape. Restraints kept bodies pinned while contaminated water washed over them again and again.

The ship rose on a wave, paused, then plunged hard enough to lift restrained bodies briefly before slamming them back down. Timbers groaned. Crew shouted orders overhead. Captives cried out convinced they would drown restrained in darkness.

The storm lasted four days. During that time, the crew brought no food or water below deck. Their own safety took priority over preserving the cargo. The captives existed in thirst, hunger, violent motion, and fear that the next wave would end everything.

When weather cleared, Dr. Thompson descended to assess damage. Eighteen more captives had died—some from injuries, others from drinking contaminated water in desperation, a few from what looked like pure psychological collapse. Bodies were removed and thrown overboard. The deck was hosed down without moving survivors first, cold water on raw fear.

Captain Davies had departed Africa with 140. By this point, the total dead had reached 42. That number mattered to the Royal Africa Company as a loss rate—30%—a line between profit and reprimand. For the survivors, numbers didn’t comfort. They only proved how easily life could be converted into arithmetic.

After the storm, conditions worsened in a different way. With fewer captives, the crew had even less incentive to maintain minimal cleanliness. Infections followed injuries. The ship’s surgeon still offered no real care. His role was to monitor whether bodies would survive long enough to sell.

During the ninth week, something shifted in Kunta’s mind. Sustained trauma had begun to erode his sense of self. He had watched men lose their minds, watched death become routine, felt identity fragment under the assault on humanity. But one thing remained beyond their reach: his name.

In Mandinka culture, names carried power. They connected you to ancestors, defined your place, held your essential identity. Kunta meant whole. His father had chosen it to mark destiny. As long as Kunta remembered his name, remembered his lineage, remembered the naming ceremony, some core part of him remained beyond British control.

He began a private ritual. Each morning during the brief deck exercise, he silently recited his full lineage. I am Kunta Kinte, son of Omoro Kinte, grandson of … he followed the chain back as far as memory carried. He recalled specific lessons about blacksmithing and drumming, the taste of foods from his village, the sound of his mother’s voice. These memories became resistance, proof he existed as a complete person, not merchandise.

Other captives nearby began to lose their names. Under relentless trauma, memory blurred. Men who had boarded knowing exactly who they were struggled to recall basic details. Languages blurred. Cultural practices became half-remembered dreams. The British didn’t have to actively erase identity. The conditions did it for them.

Kunta refused to let that happen. He held his name like a weapon no one could confiscate.

In the eleventh week, the Lord Ligonier sighted the North American coast. The crew’s behavior changed. They cleaned the ship more thoroughly, repaired damaged equipment, improved food slightly. Not from compassion, but because market value depended on appearance. Buyers in Annapolis would inspect the cargo. Weak or diseased captives sold for less.

On September 29, 1767, the ship entered Annapolis Harbor. For the captives, the end of the voyage brought an impossible mixture: relief at surviving and dread at what land meant. The journey that had killed 42 was over. The next chapter—decades of enslavement—was about to begin in a place whose language and customs were utterly alien.

Maryland officials boarded to verify the manifest and collect duties. Captives were brought up in small groups, still restrained, for preliminary inspection by potential buyers. Auctions typically occurred within a week to minimize feeding costs.

Kunta’s first sight of Annapolis overwhelmed his senses. Wooden buildings with peaked roofs, cooler air, people almost entirely white. Only a handful of Africans visible on the docks, moving with the practiced quiet of those who had learned where eyes landed.

On October 1, 1767, the Maryland Gazette ran an advertisement: “Just imported in the ship Lord Ligonier, Captain Davies, from the River Gambia, a cargo of choice, healthy slaves, for sale at Annapolis on Tuesday the 7th of October.” The phrase “choice, healthy” was the language of industry, the final polish on a process that had turned people into equipment. The 42 dead were not mentioned. The trauma of the 98 survivors was irrelevant. What mattered was availability.

The auction took place at a tavern near the docks. Buyers inspected teeth, checked for signs of illness, assessed strength. Some asked the surgeon about origins, believing certain African peoples made “better workers.” He described the group as Mandinka, “suitable,” “less prone to escape.” The assessment was wrong, and the confidence behind it revealed how shallow colonists’ understanding of African societies was. They treated captured peoples as interchangeable.

John Waller arrived representing his family’s tobacco plantation in Spotsylvania County, Virginia. The Wallers were prominent landowners, operating multiple properties worked by dozens of enslaved people. John needed young men to replace workers lost to disease or injury. He brought enough funds to purchase three or four.

When John examined Kunta, he saw what he wanted: a teenage male with visible strength, no obvious illness, compact build suggesting endurance. Kunta met his eyes directly. A more experienced enslaver might have recognized defiance. John interpreted it as intelligence.

The bidding was brief. John offered a competitive price and secured the purchase. The transaction was recorded in commercial terms: “One negro male, approximately 17 years old, paid in full, transferred to John Waller of Spotsylvania County.” Kunta had been the British crown’s property aboard ship. Now he was private property, with John Waller holding legal rights over him as over equipment.

The journey from Annapolis to Spotsylvania took three days by wagon. John transported his new purchases in the cargo bed, restrained, with minimal food and water. Not necessarily from personal cruelty, but because it was standard practice. The message was always the same: from the first moment, you learn your status.

During the journey, John attempted to teach basic commands: work, stop, food, sleep. Kunta understood nothing. English sounded harsh and angular, unrelated to Mandinka. Without shared language, communication happened through gesture and repetition, with violence as the primary tool for enforcing compliance.

The Waller plantation sat along the Rappahannock River—hundreds of acres, tobacco primary, corn and vegetables for local use. The labor force included around 30 enslaved people, many Africa-born, some second-generation. A white overseer named Connelly managed daily operations with intimidation and selective violence.

When Kunta arrived, the enslaved community watched with wary calculation. New arrivals changed everything. Would he speak any common language? Did he have skills that might earn lighter work? Would he draw attention and bring punishment down on everyone?

John Waller’s first order of business was renaming. In his ledger he wrote: “Negro male purchased Annapolis October 1767, given the name Toby.” The entry was small, bureaucratic. It was also a weapon.

African names, colonists said, were too hard to pronounce. The deeper truth was simpler: an African name carried identity that had to be erased. A man called Toby had no connection to Africa, no history beyond what his owner allowed, no self beyond property.

When Connelly introduced Kunta to others using the new name—pointing and repeating “Toby”—Kunta responded instinctively.

He pointed to himself and said clearly, “Kunta Kinte.”

Connelly assumed he didn’t understand and repeated louder. “To-by.”

“Kunta Kinte,” he insisted again.

In that moment, the fundamental conflict became explicit. John Waller owned Kunta’s body and labor. But Kunta’s name—the core of his identity—remained his own unless he surrendered it.

Connelly’s solution was violence. He struck Kunta, repeated “Toby,” demanded compliance. Kunta maintained eye contact and repeated his real name. Connelly struck harder. Kunta repeated it again.

What the white men failed to understand was that they were encountering Mandinka values that had sustained people for centuries: names carried power, identity transcended circumstance, and accepting a false name meant losing something more essential than comfort.

This confrontation continued for days. Each time someone called him Toby, he corrected them, and each correction earned punishment—beatings, reduced rations, isolation. The other enslaved people watched with mixed emotion: admiration, fear, frustration. Resistance could bring collective consequences.

An older man named Fiddler, Africa-born but in Virginia for forty years, approached Kunta during a break. In broken Mandinka mixed with English, he tried to explain: accept the name publicly, keep your true identity privately. Survive first.

But Kunta could not accept that compromise. His father had taught him that partial surrender becomes complete surrender. If he said Toby even once, he acknowledged the enslavers’ power to define him. That acknowledgment was the first step toward becoming what they claimed him to be.

On the fourth day John Waller brought Kunta to the main house for what he called a lesson. Kunta was bound to a post in view of other enslaved people. Waller explained through Connelly’s translation that Kunta would be whipped until he accepted the name. This wasn’t punishment for a specific act. It was an educational display of absolute power.

The question repeated after each strike: “What is your name?”

Kunta answered, “Kunta Kinte.”

Another strike.

“What is your name?”

“Kunta Kinte.”

The punishment continued until Kunta lost consciousness. When he woke hours later in the quarters, injured and shaking, he was surrounded by Africans who had watched it all. Their faces showed sympathy, fear, resignation—and something else. Despite the pain, Kunta had never said Toby. He had passed out before surrendering his identity.

That fact traveled faster than any official record. In places where paper denied humanity, memory did the recording.

The next morning, still injured, Kunta was sent to field labor under Connelly’s supervision. Tobacco cultivation was brutal work: planting by hand, constant weeding, removing pests, topping plants, harvesting at precise times, curing leaves. The work demanded knowledge Kunta did not have. Connelly taught by demonstration once, then punishment for failure.

Kunta lived his first weeks in constant confusion, never certain what was expected. Yet he possessed something his captors didn’t recognize: observational skills from blacksmith training. A blacksmith learned by watching subtle changes—color, sound, timing. Kunta applied those skills to field routines. He watched not just what others did, but the sequence. Within two weeks he could follow the patterns well enough to avoid most punishment, moving steady, head down, reading the day like a tool he could learn to use.

The enslaved people noticed. Many newly arrived captives moved like ghosts for months, shock hollowing them out. Kunta was traumatized, yes, but alert in a way that suggested his mind had not been taken.

His father had raised him two miles from a British fort. Freedom was fragile, Omoro had taught. It can be stolen in a moment. But inner identity—who you are—cannot be taken unless you hand it over.

As winter approached, John Waller occasionally tested whether the lesson had “worked,” calling him Toby and watching his reaction. Kunta either stayed silent or corrected with his real name, earning a cuff but not the full punishment that might reduce labor value. Waller assumed time would grind down resistance. He didn’t see what the enslaved community saw: each day Kunta held his name, he won a small victory against the machinery designed to erase him.

And then Kunta decided that survival without freedom was not the only measure of living.

Virginia winter was a new kind of suffering for someone raised in tropical West Africa. Cold invaded bones. Frost damaged fingers during early work. Respiratory illness moved through cramped quarters. Several enslaved people died and were buried without markers at the edge of the property, as if even death required no acknowledgment.

In January 1768, Kunta made his first escape attempt. He knew almost nothing about North American geography. He understood only that Africa lay across a vast body of water. His plan was simple and nearly impossible: flee at night, move away from the plantation, follow waterways that might lead to the coast, find other Africans, find some path back to freedom.

Success was unlikely. But Kunta understood that resistance still mattered, even when it failed. Sometimes refusing to accept your cage is the last proof you’re alive.

He waited until midnight, slipped out through a damaged rear door, moved cautiously in the cold. He followed a creek bed heading roughly north, reasoning water led to rivers, rivers led to something larger.

Near dawn he heard dogs.

The sound meant only one thing: the plantation had discovered his absence, and professional slave catchers were coming. Tracking hounds trained specifically for this work could follow scent for miles. The system was built to hunt.

Connelly returned earlier than expected, noticed the absence at morning call, contacted Thomas Matthews, a professional slave catcher operating throughout Spotsylvania County. Matthews had trained dogs and assistants. His payment structure was simple: fee for recovery, plus expenses, and permission to use force as long as the captive survived and could work again.

Kunta covered perhaps eight miles before the dogs caught him in a clearing. Matthews’ men surrounded him, restrained him, and walked him back with a rope, parading him on main roads in daylight as a warning to others and an advertisement for Matthews’ services.

When they returned, John Waller ordered punishment designed not just to hurt, but to terrify. Kunta was bound to the same post. The question repeated in different forms: “Will you run again?” The expected response was begging, submission. Kunta remained largely silent, drawing on endurance that disturbed Waller more than screams would have. Silence meant something inside him was beyond reach.

After enough punishment to leave him barely upright, Waller ordered him confined in a shed for a week with minimal food and water. Isolation gave Kunta time to think. The attempt had failed, but it taught him something. The plantation relied less on walls than on fear. The prison was psychological: the knowledge that dogs and men would hunt you, and punishment would follow.

When he returned to work, the other enslaved people treated him with respect and worry. They couldn’t speak openly about escape, but solidarity showed in small ways: a bite of food shared, a whispered warning, Fiddler teaching him more English.

As spring arrived, Kunta’s English improved enough for basic commands. He began to understand the scope of the system. Hundreds of plantations in the county. Thousands across Virginia. An economy built on enslaved labor. Terror reinforced by law. A society where enslaved Africans outnumbered whites in many places—yet whites maintained control through violence and the power to define reality.

Fiddler explained something Kunta found hard to grasp: there were people born into slavery in Virginia, who had never seen Africa. Second and third generation enslaved people spoke English, practiced Christianity, had no direct memory of African life. Enslavers considered them “easier.” That detail forced Kunta to confront a terrible truth: this wasn’t a temporary crisis. It was a system designed to reproduce itself across generations.

In May 1768, Kunta attempted escape again with slightly more planning. He had hidden scraps of food, chosen routes along roads, prepared simple English phrases to buy time if questioned. He lasted three days before Matthews’ dogs found him hiding in a barn about twenty miles from the Waller plantation.

This time, Waller escalated punishment to make further escape physically difficult. The method—permanent maiming—was a practice used often enough in the region that it had procedures and justifications. It was described in the language of “prevention” and “property management,” as if the act were practical rather than horrific.

A physician in the Waller family performed the procedure without anesthetic. The pain was part of the deterrent. The act’s purpose was clear: limit movement, keep labor value, remove the possibility of running.

What records can’t fully capture is what this did to a human mind. From Waller’s view, he was modifying property to prevent loss. From Kunta’s view, he was experiencing a kind of state-sanctioned torture carried out by men who believed they had moral and legal right to permanently harm another person.

The act achieved its physical goal. Kunta would never run effectively again. But it had an unintended consequence. It turned Kunta into a story that traveled. The African who tried to escape twice despite knowing the cost. The man who endured maiming rather than surrender completely. The one who still said his name.

Symbols are dangerous in systems built on obedience.

During recovery, Kunta spoke more with Fiddler and others. He learned how enslaved people preserved dignity in secret ways: family ties across plantations, hidden gatherings, the passing of stories, the teaching of children about freedom even when freedom seemed impossible. He learned too that survival took many forms. Some people cooperated for small privileges. Some embraced Christianity as a way to hold hope. Some compartmentalized, performing obedience while keeping a private self intact.

Kunta realized his strategy—absolute refusal, open defiance—was only one method among many. Others weren’t weak. They were answering an impossible question differently: how to remain human when a system is built to erase humanity.

When he could work again, his assignments changed. Limited mobility meant less field labor. He was moved toward tasks requiring less constant movement—garden work, later driving a buggy for the Waller family. This brought him closer to the enslavers’ domestic world. He observed their routines, their social visits, their prayers, their casual discussions about enslaved people as if speaking about livestock.

The most disturbing realization was not that these people were monsters in a storybook sense. It was that many were ordinary people raised in a society that normalized absolute power over Black bodies. They went to church. They loved their children. They spoke of morals. And they owned human beings without the moral dissonance cracking their faces.

Normalized evil was still evil. But it meant the problem was bigger than a handful of cruel men. Slavery was woven into law, religion, economics, and daily custom. It didn’t survive because it was questioned; it survived because it was assumed.

And yet, in that vast machine, one man held one line.

In the plantation ledger, Waller’s ink insisted: Toby. In the ship manifest, Captain Davies’ ink insisted: male, approximately 17, Mandinka. In the archive room, the page insisted: 98 delivered, 42 lost.

But in the private space no ledger could enter, Kunta insisted: Kunta Kinte.

He said it when he was hungry. He said it when he was punished. He said it when English pressed in from all sides and tried to replace his language. He said it when pain tried to make him forget. Each time he said it, he was doing something the system could not tolerate: he was naming himself.

Decades later, families would repeat that name even when it was dangerous. Parents would whisper it to children like contraband. Elders would tuck it into stories the way you tuck a seed into soil, hoping one day it would surface where light could reach it. Plantation ledgers might omit living memory. Bibles might refuse to acknowledge lineage. But memory, passed through breath and story, is harder to confiscate than paper.

Back in the archive room, the researcher’s fingers hover over the manifest page. The US flag magnet catches the fluorescent light and throws a tiny reflection onto the old ink. It feels almost insulting—modern patriotism pressed against a document that records a nation’s unspoken foundations. The iced tea sweats. Sinatra croons. The paper stays quiet.

But the name does not.

And that is the debt America never wanted to pay: not only that 98 arrived and 42 did not, but that one of the survivors fought a fifty-five-year war against erasure using the one weapon left to him—his own identity—until it outlasted the men who tried to rename him.

Some people think history is what happened. The truth is, history is also what someone tried very hard to make you forget.

News

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!

26 YO Newlywed Wife Beats 68 YO Husband To Death On Honeymoon, When She Discovered He Is Broke | HO!!…

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!

I Tested My Wife by Saying ‘I Got Fired Today!’ — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything | HO!!…

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!

Pastor’s G*y Lover Sh0t Him On The Altar in Front Of Wife And Congregation After He Refused To….. | HO!!…

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!!

Pregnant Wife Dies in Labor —In Laws and Mistress Celebrate Until the Doctor Whispers,”It’s Twins!” | HO!! Sometimes death is…

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI Came | HO!!

Married For 47 Years, But She Had No Idea of What He Did To Their Missing Son, Until The FBI…

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!!

His Wife and Step-Daughter Ruined His Life—7 Years Later, He Made Them Pay | HO!! Xavier was the kind of…

End of content

No more pages to load