The Alabama Macabre Widow Who Sheltered 25 Runaway Slaves Beneath Her Plantation: The Secret of 1850 | HO

I. The Widow of Willow Creek

The Alabama sun does not forgive. It bleaches bones, burns crops, and whitens the columns of forgotten houses until they look like tombstones.

Fifteen miles outside Montgomery, along a quiet bend of the Alabama River, stood one such house—Willow Creek Plantation, built in 1798 and whispered about for more than a century.

Its mistress, Elizabeth Caldwell, was an enigma in life and a ghost in history. In 1851, she was twenty-seven years old, childless, recently widowed, and, by all appearances, a woman of unremarkable social consequence. But beneath the genteel façade of antebellum Alabama, Elizabeth Caldwell was hiding something that would make her a myth—the kind of story told in hushed voices by lantern light.

A single line in the Montgomery County ledger marked the beginning of her legend:

“Inquiry requested into unusual activity at Willow Creek Plantation—denied due to insufficient cause.”

No explanation followed. No inspection was ever made. But those who later dug through the archives would realize that something impossible had occurred at Willow Creek: cotton yields 30 percent higher than any plantation in the county—produced by only two-thirds of the workforce.

The arithmetic did not make sense.

Nor did the silence that followed.

II. The Death of a Master

Two years earlier, Elizabeth had been a different woman—timid, quiet, rarely seen outside the house. Her husband, Thomas Caldwell, was one of those plantation men whose reputation stretched farther than their land. He was known for efficiency, cruelty, and an obsession with order.

Neighbors described him as a man who “counted his slaves like coins.” Dr. Samuel Whitaker, the family physician, called him “a patient without conscience.”

Then, in the spring of 1849, Thomas Caldwell died suddenly—“brain fever,” according to the death notice. No autopsy. No inquiry. Just a closed casket and a whisper that the widow had inherited everything.

Society expected her to remarry quickly or sell the estate. Instead, she did neither. She dismissed the overseer, freed no one, sold fifteen able-bodied men to another plantation, and reduced her workforce to thirty-eight—mostly women, children, and the elderly.

By every economic measure, Willow Creek should have collapsed. Yet within a year, production soared. The cotton wagons leaving her property doubled. The dock records in Montgomery listed her shipments as “abnormally high.”

Something was happening at Willow Creek, and no one could explain it.

III. The Stranger in the House

The first to sense it was Dr. Whitaker.

On December 12, 1850, he was summoned to the plantation for what Elizabeth called “a matter requiring discretion.”

He expected illness, perhaps childbirth. What he found instead was order—immaculate grounds, polished floors, and a mistress transformed.

“Where once there was trembling,” he wrote in his journal, “there is now command.”

Elizabeth greeted him not as a patient, but as a superior directing a subordinate. She requested bandages, laudanum, quinine, splints, and antiseptics—but would not permit him to examine the wounded. “Farm accidents,” she said.

Whitaker’s professional instincts told him otherwise. The pattern of supplies suggested broken bones, infections, and something else—injuries of flight.

On his third visit, he noticed a draft near the library wall. When he moved a bookcase, it swung open, revealing a hidden staircase descending into darkness. Before he could investigate, Elizabeth appeared silently behind him.

“The look she gave me,” he wrote later, “was that of one cornered between heaven and damnation. I believed, in that instant, she might kill me.”

He did not return for weeks. When he did, he recorded one final cryptic entry:

“I have made a grave error in judgment. God forgive me for what I now know, and have agreed not to reveal, of what lies beneath Willow Creek.”

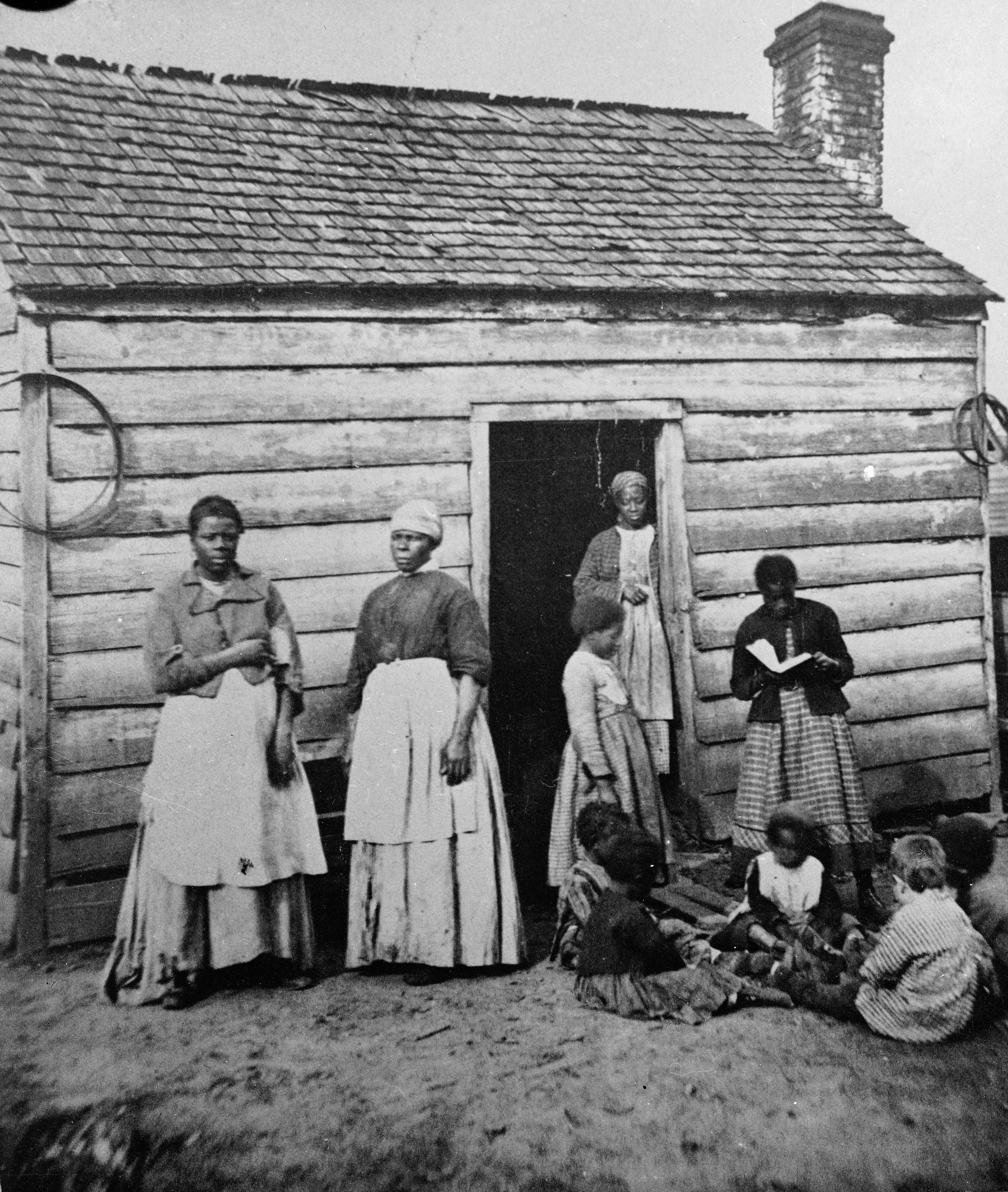

IV. Beneath the House

The truth of those words would not be uncovered until 1967.

During a structural survey of the ruins—long after the main house burned in 1938—historians discovered a subterranean labyrinth beneath the foundations: chambers carved from limestone, with beds of straw, a cooking area, and a system of vents hidden within the chimneys to disperse smoke.

The rooms were not on any blueprint. One tunnel led to the riverbank, cleverly disguised among the willow roots.

How long it had been there, no one could say. But the signs of habitation were unmistakable—fire pits, tin cups, fragments of clothing, and a rusted lantern engraved with a single letter: E.

The archaeological team concluded that the underground complex could shelter as many as twenty people at a time.

It was, in effect, a refuge—built beneath the home of a slave owner.

V. The Girl Who Heard Voices

One of the few contemporary witnesses to sense something wrong was Abigail Foster, the eighteen-year-old daughter of a neighboring landowner.

Her diary, found a century later among family papers, reads like the testimony of someone hovering between curiosity and terror.

In November 1850, her father began visiting the widow under the pretext of business. He often brought Abigail along, believing her presence “added civility.”

“The widow is nothing like what I expected,” Abigail wrote. “She speaks softly but sees everything. Her house is silent as a chapel.”

On one visit, while waiting alone in the parlor, Abigail heard the sound of children laughing—beneath her feet.

“It came from under the floor,” she noted. “When I asked, Mrs. Caldwell smiled and said it must be the kitchen staff’s children outside. But there were none.”

By January, her entries turned fearful. The widow invited her to tea alone and asked strange questions about her father’s estate—cellars, exits, and servants’ quarters.

Abigail’s last entry, dated March 12, 1851, reads:

“I have seen what lies beneath. She knows I saw. She is deciding what to do with me.”

A week later, Abigail was sent to relatives in Philadelphia. She never returned to Alabama.

VI. The Discrepancy

Meanwhile, others began to notice what the numbers couldn’t hide.

A tax assessor named James Harrow visited Willow Creek in February 1851. His official report was routine—nothing unusual. But a private letter to his brother, found a century later, tells a different story.

“The fields are perfect, yet I saw no more than twenty workers at labor. The yield is impossible. The people move as if rehearsed, each task performed in eerie silence. When I questioned one woman, she said, ‘Mistress takes good care of those who work hard.’ It chilled me.”

Harrow requested permission for a formal investigation. Three months later, he was dead—“heart failure,” though he had no prior condition. His request vanished from county files.

The silence returned.

VII. The Ledger of Initials

In 1960, during cataloging of plantation documents, archivists discovered a false compartment in Elizabeth Caldwell’s writing desk. Inside lay a slim leather ledger filled with initials and brief notes:

“J.T.—arbound.”

“L.H.—seabbound.”

“E.M.—north via Rev.”

Historians recognized the code: arbound for Ohio River routes, seabbound for ships leaving Mobile, Rev for reverend or religious contact.

There were twenty-five names.

If the interpretation is correct, Elizabeth Caldwell may have helped at least twenty-five enslaved people escape to freedom between 1849 and 1851—using the plantation’s underground network as a temporary station on the southernmost branch of the Underground Railroad.

If true, she was operating the most dangerous abolitionist outpost in the Deep South—under the nose of Montgomery’s elite.

VIII. The White Witch of Willow Creek

For decades after the Civil War, former slaves in Montgomery County spoke of a woman they called “The White Witch of Willow Creek.”

She was not a witch of spells, but of vanishing acts. People said she could make the enslaved disappear “as if the earth swallowed them whole.”

A story told by an elderly woman to historian Rebecca Thornton in 1969 described her as “a lady with eyes that could see in the dark, who led people through tunnels without a light.”

Children were warned never to speak her name aloud. Adults called her only “the Lady.”

IX. The Arrow and the Map

In 1958, highway construction crews unearthed a set of stone markers half a mile from the former plantation. When viewed from the air, they formed an arrow pointing north.

Beneath the final stone, buried three feet deep, was a metal box containing a hand-drawn map of river tributaries leading from Montgomery toward Tennessee. The handwriting matched Elizabeth’s.

Along the map’s edge was a code later deciphered using biblical references common among abolitionists. It read:

“Two souls delivered from bondage into light. More will follow. The river remembers what humans choose to forget.”

It was signed with a single initial: E.

X. The Reverend’s Letter

Further evidence surfaced in 1964 in the attic of a Massachusetts home once belonging to Reverend William Parker, a northern missionary who had lived in Montgomery in the 1840s. Among his papers was a letter addressed only to “E.”

“Your position remains uniquely valuable. Continue as you have been—observing all while appearing to see nothing. The time for direct action will come. Patience in the service of righteousness is no sin.”

Dated 1847, the letter predates her husband’s death by two years—suggesting Elizabeth may have been a covert sympathizer long before she took open action.

XI. The Doctor’s Secret

The most damning evidence of all came not from her, but from Dr. Whitaker.

In 1968, his descendants discovered a hidden compartment in his writing desk containing an unsigned letter, dated August 18, 1865, from Philadelphia:

“What Elizabeth Caldwell created beneath her plantation was nothing short of remarkable—a haven of hope in the darkest place imaginable. I treated twenty-five souls in her underground rooms between 1849 and 1851. Some bore injuries from escape. Others carried wounds no medicine could mend. Each stayed only as long as needed before being moved north. The remaining servants above were not ignorant—they were her allies. She offered them a choice: aid her in exchange for eventual freedom or be sold. Not one refused.”

The letter ends with a reflection that reads like both confession and eulogy:

“She once told me, ‘Some see the world as it is and accept it. Others see the world as it should be and make it so.’ I do not know what became of her. Perhaps it is better if history does not. The most effective rebellion is often the one that leaves no trace.”

It was signed only S.W.

XII. Disappearance

In April 1851, Elizabeth sold the plantation to a merchant from New Orleans and vanished.

A week later, an arrest warrant was issued for her—accusing her of “theft of property” (meaning slaves) and “incitement to insurrection,” both capital offenses. The warrant was never served.

On the back, in the sheriff’s handwriting, were five haunting words:

“The widow has gone. Let it rest.”

XIII. The River Widow

In 1852, a register from a Canadian church listed three newly arrived families. Beside their names was a note: “Delivered by the River Widow.”

No one knew who the River Widow was.

But among the initials in Elizabeth’s coded ledger were three that matched those families.

The handwriting on the church register matched hers too.

XIV. The Possible Endings

What happened to Elizabeth Caldwell after 1851 remains a riddle wrapped in rumor.

Some say she boarded a ship to England under her own name, carrying six trunks and a forged passport. Others claim she surfaced in Boston as Elizabeth Rivers, a philanthropist who donated to abolitionist causes but refused to speak publicly.

A few descendants of freed slaves insist she lived among them in disguise—teaching children to read, memorizing escape routes, disappearing each time slave catchers drew near.

No grave bearing her name has ever been found.

XV. The Final Artifact

In 2002, ground-penetrating radar mapped the tunnels beneath the old plantation site. Beneath what would have been Elizabeth’s study, researchers found a small sealed chamber. Inside, they discovered a single object:

A gold wedding band engraved with four words—

“Until all are free.”

The ring now sits in the Alabama History Museum, labeled simply:

Artifact from Willow Creek Plantation. Ownership unconfirmed.

XVI. The Legacy of Silence

Historians of the Underground Railroad often say its history was designed to disappear.

Every successful escape erased its own evidence. Every unrecorded act of defiance was its own protection.

If Elizabeth Caldwell truly ran a southern station—feeding, sheltering, and guiding fugitives beneath the very structure of slavery—then her greatest success was not the twenty-five lives she may have saved, but the century of silence that followed.

Because that silence meant she had never been caught.

As historian Rebecca Thornton wrote in her 1969 study The Widow’s Labyrinth:

“The most effective resistance often leaves the lightest footprint in the historical record.”

XVII. The Ghost of Willow Creek

Today, the land where Willow Creek stood is private farmland.

Nothing remains but a fragment of foundation and a line of ancient willow trees that bend toward the water. Locals say the air there feels “too still,” as if holding its breath.

Some swear that on quiet nights you can hear the faint sound of footsteps underground—or the laughter of children where no children play.

But most who visit feel only a heaviness, a kind of watchful quiet, as though the ground itself remembers the fear and the faith of those who once passed beneath it.

Perhaps it is imagination. Or perhaps, as the coded map once said,

“The river remembers what humans choose to forget.”

XVIII. Epilogue

Elizabeth Caldwell’s name does not appear in Alabama textbooks.

Her portrait, if it ever existed, has vanished.

But the fragments—ledgers, maps, rings, and whispers—tell a story of a woman who lived two lives: one above ground, obeying the rules of her world, and one below, dismantling it in silence.

Whether driven by faith, guilt, or love, she became both ghost and savior—proof that even in the heart of a system built on chains, there were those who dug tunnels toward light.

And if history never fully proves her story, perhaps that is fitting.

Because her truest legacy is the same one she gave to those she hid:

freedom bought by secrecy.

News

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis | HO!!

He Traveled to Texas to Meet His 22-Year-Old Online GF, He Killed Her After Seeing She Had a P#nis |…

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!!

ELIZABETH KECKLEY: Lincoln’s dressmaker who was born a slave — THE SECRETS SHE KEPT FOR 50 YEARS | HO!!!! The…

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him! | HO!!!!

Karen Broke Into My Garage to ‘Inspect’ It – So I Locked the Door and Called the Sheriff… I’m Him!…

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!!

Dutch Schultz Sent 10 Men to Take Harlem — Bumpy Johnson Sent Them Back in 10 COFFINS | HO!!!! For…

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!!

Bruce Lee’s Grave Was Opened After 52 Years, And What They Found Shocked Everyone! | HO!!!! That early fire, unpolished…

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!!

Little Girl Vanished in 1998 — 3 Years Later, Sister Told the Police What She Saw | HO!!!! The grass…

End of content

No more pages to load