The Bizarre Mystery of the Abominable Female Slave Who Became the Mistress of the Plantation | HO

Among the thousands of antebellum plantation records stored in rural Georgia’s archives, one ledger has baffled, unsettled, and divided historians for more than half a century. The entry—dated March 1851—described a female slave with skin so “abominably disfigured” that overseers initially refused to work near her. And yet, seven years later, this same woman would own the entire estate, control its operations, and bury its master under circumstances so controversial that state officials sealed the case for more than a century.

Her name, at least the one recorded, was Sarah.

And the dark, twisting story of how she transformed from “property” purchased for $30 into one of the only known Black female plantation owners of the pre–Civil War South remains one of the strangest and most inexplicable episodes in Southern history.

This is the mystery that scholars still whisper about.

This is the tragedy that Georgia once tried to hide.

This is the forbidden saga of the abominable one.

I. A WORLD BUILT ON Rigid Order—and Fear

Wikliffe Plantation sprawled across 1,200 acres of Hancock County in the late 1840s, surrounded by neat rows of cotton and the strict, airtight social codes that governed the planter aristocracy. It was a kingdom built on predictability: profit margins, yield counts, status rituals, and the immutable divide between master and slave.

Its owner, Thaddius Havford, was the kind of man plantation society trusted.

Precise. Controlled. A widower devoted to ledgers and logic.

Every birth, every bale of cotton, every illness was recorded in his personal hand. He was respected for his discipline—and quietly pitied for the loneliness that followed the death of his wife and child.

Nothing in his orderly world prepared him for the arrival of the chained coffle one rain-soaked day in October 1849.

Seventeen enslaved people stepped off the wagons, dazed, exhausted, and coated in dried mud. Their trader tried to hurry Thaddius past the last woman in line.

“She’s damaged goods,” he warned. “Nobody wants trouble that spreads.”

But Thaddius asked to see her.

And the trader reluctantly pulled down the collar of her dress.

Her skin was mottled with stark white patches—across her neck, chest, arms, hands—so sharply contrasted against her dark complexion that the effect was almost shocking. Not contagious, not fatal—but visually jarring in a society obsessed with appearance, “purity,” and physical order.

The overseers recoiled.

One planter gagged.

The trader muttered, “Abominable.”

Thaddius wrote three words into his ledger:

“Appearance disturbing. Useful intelligence unknown.”

He purchased her for nearly nothing.

A decision that would eventually tear apart everything he had built.

II. The Woman They Tried to Hide

At first, Sarah existed on the margins of Wikliffe—sleeping in a converted store room, eating alone, working in silence behind the kitchen house. The other enslaved workers refused to share quarters with her. The domestic staff avoided eye contact.

Only one person noticed the truth beneath the white-scattered skin.

Dela Puit, the free woman of color who managed the household, saw something unusual in Sarah. The way she scanned rooms. The way she memorized details. The way she could read—fluently—and calculate figures faster than most clerks.

When a newspaper was left on the kitchen table, Sarah quietly recited the entire thing from memory that evening—commodity prices, political gossip, even the sheriff’s announcement about stray livestock.

She reorganized the storeroom overnight using a mathematical approach no one at Wikliffe had seen.

She was a mind trained in secrecy.

And Dela reported it.

Thaddius’s reaction was immediate:

“Put her in the ledgers. Let me evaluate accuracy myself.”

The accuracy was staggering.

And in that private study, between inventory columns and rainfall charts, something unthinkable began to take shape:

a connection.

a recognition.

a dangerous meeting of minds between a slave and her master.

III. The Forbidden Partnership

By January 1850, Sarah was spending her afternoons in Thaddius’s study—drafting correspondence, reorganizing decades of records, correcting accounting errors he had missed for years.

They ate meals together when work ran late.

They debated literature.

They discussed crop rotations, tariff laws, and constitutional philosophy.

This was not seduction.

Not yet.

It was something more radical.

Two people—one legally human, one legally property—discovering intellectual equality in a place built on the denial of it.

And plantation society noticed.

Rumors swelled.

The plantation next door began whispering about impropriety. The Sparta Tavern filled with talk of the “creature in the study.” Overseers muttered about “unnatural intelligence” and “witchcraft.”

One man—Daniel Tucker—put it plainly:

“She’s poisoning the order of things. She’s got him thinking wrong.”

It was the first omen that Wikliffe Plantation was drifting into forbidden territory.

Then came the fever.

IV. Plague, Death, and the Night Everything Changed

The summer of 1850 brought a drought so brutal it cracked the earth and drained the wells. Pestilence followed. The fever swept the fields like fire—killing some workers in hours, others over agonizing days.

Thaddius worked himself into collapse trying to manage the crisis.

Sarah never left his side.

She organized the infirmary, tracked symptoms, predicted deaths before the doctor could. People who once recoiled from her skin now clung to her competence. She saved lives. She catalogued the plague with detached precision.

And finally, as the fever ate at Thaddius’s mind, she stayed in his bedroom.

He woke delirious one night and thought she was his dead wife.

He touched her face.

She did not stop him.

What happened next would haunt them both.

When the fever broke four days later, she sat beside him with the same steady expression she used for numbers and storms.

And she told him:

“I am pregnant.”

V. The Impossible Proposal

Thaddius felt the world tilt beneath him.

In Georgia, a child born to an enslaved woman was legally property—even if the father was the owner. Their child would be his slave.

Sarah laid out the cold truth in her calm, devastating voice:

If he freed her, the baby would be born free—but the scandal would destroy him.

If he acknowledged the child, he might be charged with “moral depravity.”

If he denied the child, he would be a coward.

There was only one path she saw:

“We marry. Legally. In a state where the law allows it.”

Pennsylvania.

Massachusetts.

Somewhere far from Georgia’s gaze.

And then they would return to Wikliffe—married under federal authority—forcing Georgia to recognize the union.

It was dangerous. Illegal. Potentially ruinous.

But for the first time in years, Thaddius felt clarity.

“Then we will marry. And whatever must burn, will burn.”

VI. The Marriage That Shook the County

They left quietly.

They traveled by coach through bitter winter cold, slept in separate rooms at roadside inns, spoke only when safe.

And on December 12th, 1850, in a small Quaker meeting house outside Philadelphia, they married—legally, fully, irrevocably.

Sarah wore a plain blue dress.

There were two witnesses, both strangers.

The record was entered into Pennsylvania’s civil registry.

That night—their first night as conscious equals—they became husband and wife in truth.

When they returned to Georgia, the war began.

Not a war of guns—but of gossip, petitions, sabotage, and legal assault.

Neighboring planters filed challenges questioning Thaddius’s sanity.

County officials issued a warrant to detain Sarah for medical examination.

Someone burned a cotton barn.

Their workers were attacked in town.

Threats arrived at their door.

And then came Robert Krenshaw, the venomous neighbor whose envy had always smoldered beneath politeness.

He filed a petition to seize Wikliffe Plantation on the grounds that its owner was morally unfit—and potentially bewitched.

Wikliffe descended into a siege.

And the birth of their child approached with terrifying speed.

VII. The Woman Who Faced a County

On the eve of the hearing that would decide their fate, Thaddius did something bold: he invited the entire county to a public forum.

He intended to argue law.

Sarah had something different in mind.

When she stood, visibly pregnant, vitiligo blazing white under the courthouse windows, the room fell into stunned silence.

Her voice did not tremble.

She dismantled centuries of assumptions in twenty minutes—speaking about humanity, intelligence, survival, and the hypocrisy of a system terrified by one Black woman who refused to remain small.

Some people wept.

Some stared.

Some clapped.

And some, like Krenshaw, were enraged beyond reason.

The next morning, the judge delivered a narrow, reluctant ruling:

The marriage was valid.

The plantation remained theirs.

But the community was not required to accept them.

They had won the battle.

But not safety. Not peace.

Not yet.

VIII. Blood in the Autumn Fields

The child was born July 3rd, 1851—a son, Thomas—light-skinned, healthy, and unmistakably Thaddius’s.

For a moment, a thin ribbon of peace wrapped itself around Wikliffe.

Then violence tore it apart.

Daniel Tucker—the overseer who despised Sarah—struck a field worker who challenged his authority. A crowd formed. Tucker drew a pistol. Thaddius arrived at the same moment Sarah stepped forward.

Tucker screamed:

“You ruined everything! You taught them they’re people!”

He pointed the gun at her stomach.

At the child she carried.

At the future.

And Thaddius made the most dangerous choice a Southern planter could make:

He sided with his wife—against a white man.

Against the hierarchy itself.

He fired Tucker on the spot.

It was the moment Wikliffe Plantation ceased being a plantation in any traditional sense.

It became a social experiment.

A rebellion contained within 1,200 acres.

A glimpse of a possible world that the South would not allow.

IX. The Years the South Tried to Forget

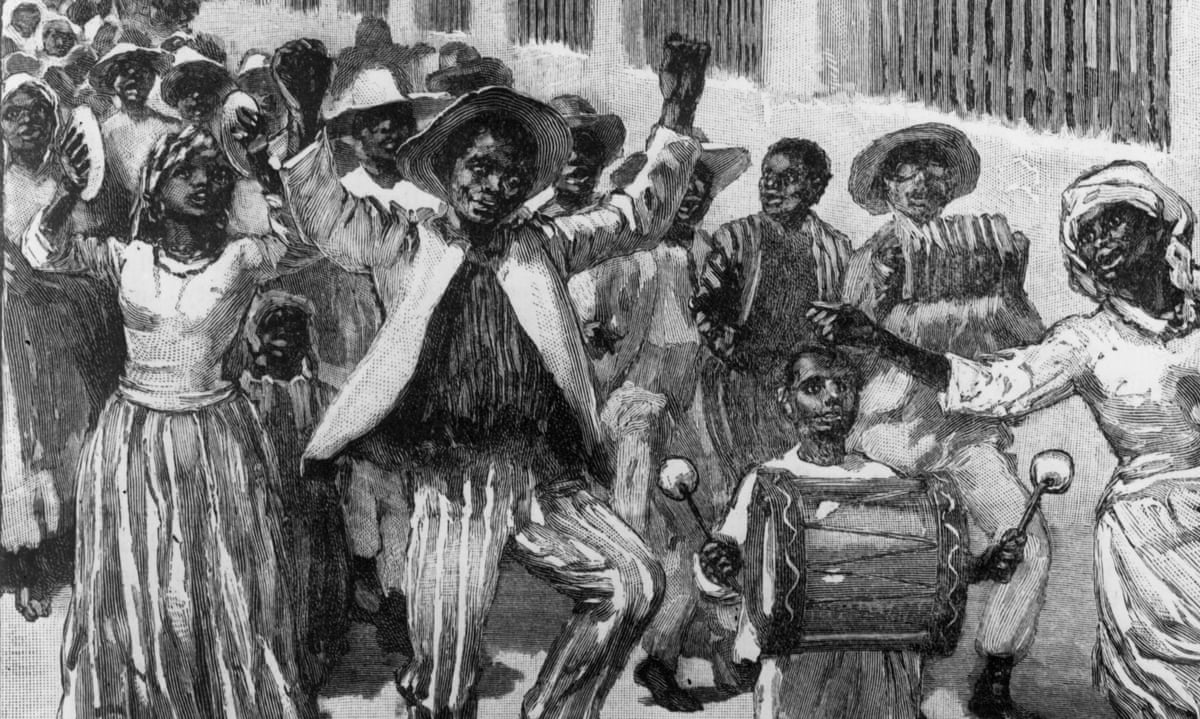

What followed was unprecedented.

Thaddius began paying wages to field workers—small amounts, symbolic but revolutionary. He allowed families to buy their freedom on generous terms. By 1855, nearly half the workers at Wikliffe were technically free. Sarah maintained all records, negotiated contracts, and co-managed the estate with effortless authority.

The neighbors shunned them.

Society erased them.

But Wikliffe endured.

When Thaddius died in 1857—worn down by years of legal battles, threats, and scrutiny—he left everything to Sarah.

It was the final scandal.

But it held.

And Sarah became one of the only Black women in the pre-war South to inherit and run a major plantation.

She kept it profitable for thirty more years.

During the Civil War, she helped coordinate escapes for enslaved people fleeing toward Union lines. After emancipation, she turned Wikliffe into a wage-labor estate—a proto-sharecropping system that still gave workers autonomy beyond anything in the region.

She died in 1902, at age 75, surrounded by grandchildren.

Her son Thomas later founded a school in Philadelphia that educated Black children for more than half a century.

Today, plantation histories mention her in footnotes, as if her life were an amusing curiosity.

It was not.

It was a revolution smothered under cotton.

X. The Real Mystery of the Abominable One

The questions historians ask today are not the ones Georgia asked in 1851.

The real question isn’t:

“How did a woman once labeled abominable become mistress of a plantation?”

The real mystery is:

Why did an entire society feel more threatened by her intelligence than by its own brutality?

Why did a $30 enslaved woman have to outthink an entire legal system to prove she was human?

And why did the world need her to fail?

The ledger that began this story—the one describing her as “damaged goods”—sits in a climate-controlled archive today, fragile and fading.

But one note stands out in ink darker than the rest:

“Expected value—uncertain.”

The most profitable decision Thaddius Havford ever made was the one society warned him against.

And the most “abominable” person on the plantation became the only one history remembers.

Wikliffe Plantation is gone now.

Time swallowed it, as time swallows all corrupt structures.

But the story of Sarah Havford—the woman they tried to hide—still burns.

Because in the end, nothing supernatural was ever needed to terrify the South.

All it took was one enslaved woman who refused to be less than human.

News

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!!

A Secret Gay Affair Between Two Inmates Ended In A 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 That Shocked Everyone! | HO!! Andre Johnson. Inmate #44702….

A Cheating Husband 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐛𝐞𝐝 His Wife 6 Times – She Came Out Of The Hospital And Sh0t Him | HO!!

A Cheating Husband 𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐛𝐞𝐝 His Wife 6 Times – She Came Out Of The Hospital And Sh0t Him | HO!!…

The Baroness Locked Her Slave With 8 Starving Dogs – The Girl Walked Out With All 8 Following | HO!!

The Baroness Locked Her Slave With 8 Starving Dogs – The Girl Walked Out With All 8 Following | HO!!…

Mother Of Three K!lled Cop Husband Over What He Kept In Basement | HO!!

Mother Of Three K!lled Cop Husband Over What He Kept In Basement | HO!! She moved to the window and…

Popular Miami Gold Digger Infected Rich Lovers With 𝐇𝐈𝐕 — It Ended In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!!

Popular Miami Gold Digger Infected Rich Lovers With 𝐇𝐈𝐕 — It Ended In Double 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 | HO!! The Miami skyline…

The Depraved Couple Who Abvsed Their 3 Days Old Daughter, Rec0rd & S0ld The T@pe Online | HO!!

The Depraved Couple Who Abvsed Their 3 Days Old Daughter, Rec0rd & S0ld The T@pe Online | HO!! How that…

End of content

No more pages to load